Britannia Beach

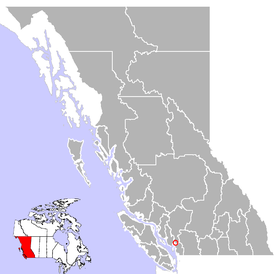

Britannia Beach is a small unincorporated community in the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District located approximately 55 kilometers north of Vancouver, British Columbia on the Sea-to-Sky Highway on Howe Sound. It has a population of about 300.

The community first developed between 1900 and 1904 as the residential area for the staff of the Britannia Mining and Smelting Company. The residential areas and the mining operation were physically interrelated, resulting in coincidental mining and community disasters through its history.

Today, the town is host to the Britannia Mine Museum, formerly known as the British Columbia Museum of Mining, on the grounds of the old Britannia Mines. The mine's old concentrator facilities, used to separate copper ore from its containing rock, are a National Historic Site of Canada.[1]

History

Britannia Beach took its name from the nearby Britannia Range of mountains, which form the east wall of the mountainous shore of Howe Sound south of Britannia Beach. About 1859 Royal Navy hydrographer Captain Richards of HMS Plumper named the range of mountains for HMS Britannia, the third of a series of vessels to bear that name. The Britannia was never in these waters.[2][3]

Copper mine (1900-1974)

A copper discovery on Britannia Mountain by Dr. A. A. Forbes in 1888 led to the development of the Britannia Mine. In 1899, a mining engineer named George Robinson was able to convince financial backers that the property had great potential. For several years, companies were formed, merged and dissolved in efforts to raise capital. The Britannia Mining and Smelting Company, a branch of the Howe Sound Company, finally commenced mining in the early 1900s, and owned the site for the next sixty years. The first ore was shipped to the Crofton Smelter on Vancouver Island in 1904, and the mine achieved full production in 1905.

A town had grown up around the mine and a Post Office opened on January 1, 1907 where it was named after the nearby mine.

In 1912 John Wedderburn Dunbar Moodie was authorized to upgrade the operation and increase production from the mine. Improvements in the mineral separation processes stimulated plans for a new mill (No. 2), which was completed in 1916 and was capable of producing 2000 tons of ore per day. The onset of World War I increased the demand for copper and the price rose sharply.

On March 21, 1915 an avalanche destroyed the Jane Camp. Sixty men, women and children were killed and it was a terrible blow to the tiny community.[4] Construction began immediately on a new, safer town at the 2,200-foot (670 m) level above the Britannia Beach site. This portion of the community became known as the "Town site" or "Mount Sheer".

In March 1921 during a brief period when the mine was shut down, mill No. 2 burnt to the ground.[5]

On October 28, 1921 after a full day of torrential rain, a massive flood destroyed much of that portion of the community and mine operations that existed on the lower beach area.[6] 50 of 110 homes were destroyed and thirty-seven men, women and children lost their lives. The flood was caused because the mining company had dammed up a portion of the Creek during the construction of a railway, and when this dam gave way the town below was flooded. Carleton Perkins Browning directed the reconstruction of this portion of the community and the new No. 3 mill, which stands today.

Being an isolated, close knit community which could only be accessed by boat, life in both of Britannia's towns was never dull. Facilities included libraries, club rooms, billiard rooms, swimming pools, tennis courts and even bowling. A thriving social calendar saw sporting events, theatrical productions, dances, movies and parties held throughout the year.

The mine boomed in the late 1920s and early 1930s, becoming the largest producer of copper in the British Commonwealth by 1929, under the management of the mine manager C.P. Browning.

In the 1940s there were talks to build an artist village in Britannia's hills, but that plan did not proceed.

Miners unionized in 1946 and suffered through their first strike. Low copper prices saw the Britannia Mine Company reduced to seven employees, and in 1959 it went into liquidation.

In 1963 the Anaconda Mining Company bought the property and production continued for the next eleven years. 300 employees managed to produce 60,000 tons of concentrate each year. Ferries services stopped around May 1965 after the highway and railway connections had been constructed. The connections made it easier to transport the copper, but high operating costs and taxes eventually forced the mine to close on November 1, 1974. The company did not attempt to clean up the mine and chemical wastes that it produced, since environmental protection laws had not yet been enacted and enforcement of the Fisheries Act was never applied. A newly elected labour government presented higher anticipated union costs and the ore vein had already been 'highgraded'. With the closure of the mine economy of the town diminished rapidly, and the railway station shut down soon after.

Mining Museum (1975-present)

In 1978 after reviewing a Lehman Brother's report that advised the Anaconda Mining Company to divest the properties as future industrialization of Howe Sound was unlikely given plans to restore and develop it as a destination tourist/recreational region, Anaconda signed an Option Agreement for Sale with Copper Beach Estates Ltd, a newly registered real estate development company that was a consortium of Anaconda business suppliers. The option agreement was conditional upon CBE Ltd. making available lands for the Historical Society (Mining Museum), remediating the pollution and maintaining the uneconomic community of resident tenants at Britannia Beach. CBE Ltd. exercised their agreement to purchase all Anaconda's assets which included thousands of acres of land, all of the mining chattels and buildings and 30,000 acres of mineral titles by selling 400 of the 3500 acres titled lands to Dome Petroleum for a gas liquification deep sea terminal at Minaty Bay. Dome was not granted the permits to proceed and sold their lands to Makin Pulp and Paper Ltd. who planned to build a coated paper mill at Britannia using aspen licences granted in northern British Columbia to create 350 resource based jobs with significant government subsidies.

Copper Beach Estates Ltd. CBE Ltd,) went through a series of shareholder ownerships initially granting the Historical Society lands outright and then through successive corporate raids sold off portions of the holdings until in the early '90's, unable to perform on an agreement for sale to 400091 British Columbia Ltd., a real estate developer, they were placed in receivership under Price Waterhouse Coopers (now Coopers Lybrand).

In 1991 another flood occurred when a dam broke, although there were no casualties this time. Britannia creek burst leaks after 50 millimeters (two inches) of rain fell in less than 24 hours. The torrent of flood water carved itself a new route, along what used to be the old creek bed, straight through town.

On April 1, 1975 the BC Museum of Mining was opened to the public, and was designated as a National Historic Site in 1988. The following year, 1989, the Museum site was designated a British Columbia Historic Landmark. The Britannia site and its historic buildings, may be familiar to fans of the X-Files series as several episodes were filmed on the site. In conjunction with the opening of a major expansion project the museum was renamed the Britannia Mine Museum in 2010.

With the closure of the mine in 1974 most of the families left Britannia and over the years fewer of the original workers remained as the community struggled not to become a ghost town. Given the condition precedent of the Agreement for Sale a group of residents negotiated to purchase the townsite spearheaded by one of the prominent residents, Laurier LaPierre and became active in pushing for a clean up of the pollution. This led directly to the agreement with Macdonald Development facilitating tenants with an opportunity to purchase the homes they occupied.

In 2001, the Province reached a $30 million settlement with the successors to the former mine owners. In summer 2003, subsequent to an agreement with the Provincial Government, the properties, including the town and thousands of acres of mineral titles was purchased by The Macdonald Development Corporation who bought out 400091 British Columbia Ltd. and secured an Order of Possession. All mineral claims were retired and assigned to the Province, including the primary contaminated areas. Macdonald, under agreement with the Provincial Government, proceeded to develop the town and surrounding area with some proceeds contributing to the Province's reclamation fund. The current residents were able to purchase the property where their homes were and many did so in November 2005, the first individual land owners in the town's history.

The Province proceeded to construct a $20 million water treatment centre to process the water pollution from the former mine, consisting of the acid mine drainage and the contaminated groundwater which formerly discharged to Howe Sound. The water treatment plant started operation on schedule on December 31, 2005. The acid mine drainage is expected to continue for hundreds of years and hence the water treatment plant is expected to be required for hundreds of years. The approximate cost for the first 20 years of the reclamation program including all initial capital and operation costs is approximately $200 million, (current charges by Epcor on a P3 agreement are approximately $1 millions annually), which will be primarily paid for by the Province. Improvements to Highway 99 and development of the waterfront accelerated in preparation for the 2010 Winter Olympics.

The large white concentrator building that dominates the town received a 5 million dollar face lift with new exterior cladding and windows. Funding came from the Federal Government, Provincial Government, industry (notably Teck Cominco, Gold Corp, Hallbauer Family Foundation and Hunter Dickinson Inc.) and private donations. The Windows on Howe Sound project campaign raised over $110,000 from individuals donating to the restoration of the Mill's windows.[7]

Britannia Creek pollution

Prior to the reclamation work undertaken by the University of British Columbia and the Provincial Government, the clear and transparent water in Britannia Creek suggested a pristine environment, however the clear water was actually an indication that no living creatures could survive in it. The water could not be consumed by humans either.

Even though mining had stopped in 1974, runoff and rainwater that flow through the mine’s abandoned tunnels combine with oxygen and the high sulfide content of the waste rock to create a condition called acid rock drainage (ARD). ARD is caused by a chemical reaction created by successive generations and species of bacteria waste stream, which results in highly acidic runoff that contains large concentrations of dissolved metals such as copper, cadmium, iron, and zinc. Prior to December 31, 2001, the polluted water was being deposited directly into Howe Sound by means of Jane Creek and Britannia Creek and as much as 450 kilograms (992 pounds) of copper was entering Howe Sound daily. A copper 'laundry' constructed by Anaconda which captured a significant part of the mineral contaminants on tin can depositories which mine effluent was directed into was no longer kept in service so that the effluent flowed directly into a deep water discharge pipe which was washed away during the 1991 floods.

A team of young chemical engineers, incorporated as NTBC tested a bio-chemical process of remediating the mine waste waters by feeding a bacterial waste stream into the effluent effectively neutralizing the acid drainage and through concentration of the mineral precipitants successfully recovered the minerals economically. Ironically this method was not employed due to the novelty of its application but it is now an industry standard internationally. Current annual costs of the lime treatment method employed by EPCOR cost the Province $1 million annually for centuries to come. The bio-chemical method would be cost neutral due to the recovery income.

A two-kilometre (1.2 mi) strip of coastal waters along Britannia Beach was seriously polluted, affecting 4.5 million juvenile chum salmon from the Squamish Estuary (half the entire salmon run). A Fisheries and Oceans Canada report revealed that Chinook Salmon held in cages off Britannia Creek died in less than 48 hours because of the toxic metals in the water, whereas fish held off Porteau Cove had a 100 per cent survival rate.

The area around Britannia Beach had become extremely polluted. Concerns about the state of both Britannia Creek and Howe Sound were frequently expressed throughout the 1980’s and 90’s by renowned river advocate, Mark Angelo, and others, who helped to increase public awareness about the seriousness of the issue. Through an extensive media campaign, Angelo profiled the state of the creek which was completely lifeless; devoid of fish and aquatic insects. He also documented the extent of the dead zone that had developed into Howe Sound near the creek’s outlet. Angelo was an early advocate of the need for a multi-pronged approach to rectifying the pollution problem. While part of this called for diverting polluted runoff from the creek, another key element, he believed, entailed the building of a treatment plant that would neutralize the acidic runoff entering into How Sound, something he felt historically responsible parties behind the pollution should help fund.

In 2001, Britannia Creek was designated by the Outdoor Recreation Council as BC’s most endangered river. The area was also designated as the "worst point source of mineral contamination in North America" by the Federal environmental Ministry. Growing public concern finally helped to spark tangible efforts to rectify the problem.

Engineers from the Centre for Environmental Research in Minerals, Metals, and Materials at The University of British Columbia installed a concrete plug in the 2,200-foot (670 m) Level adit in December 2001 as the initial step in constructing a more substantial Millennium Plug. The idea for the installation was to create a laboratory to study ways to seal mine adits using bulk materials. At the same time the installation would immediately stop all pollution from the 2200 Level into Jane Creek, a tributary of Britannia Creek. UBC researchers invited the Provincial government to participate in the project. The Province was willing to participate to the extent of providing funding for the minimum plug work required to address its needs. From the perspective of the UBC researchers this was not adequate. The UBC researchers then chose to work with the owners of the site at the time, Britannia Mine and Reclamation Corporation, with UBC and BMARC sharing equally in the cost of the project.

The concrete plug was constructed through the fall of 2001 by a Squamish company, TSS Tunnel and Shaft Sinking Ltd. The concrete plug was poured on December 20, 2001 and the effluent turned off on December 31, 2001. UBC's plan was to begin the research work to install the Millennium Plug for testwork purposes during 2001. However the ground above the mine portal began sloughing into the adit creating significant danger for further work. The Province was asked to contribute to shoring-up the roof, but once again declined stating that they saw no need for a second plug. During 2002, Macdonald Development Corporation (MDC) bought out the secured creditor, 400091 BC Ltd., to whom BMARC owed approximately $10 million. MDC then gave the bulk of the mine site lands to the Province in exchange for MDC receiving indemnification for their remaining lands which consisted of the village of Britannia Beach and some adjacent developable land.

The Province also received some limited development levies from MDC for each existing and new residential property developed. The Province now owned the main mine site lands, including the 2200 portal and plug. Since the Province did not have any legal responsibility to the agreement entered into between BMARC and UBC, and already had the concrete plug in place, the Provincial Mine Reclamation Project declined to contribute to the 2200 portal reclamation work necessary for constructing the Millennium Plug. The cost to do the stabilization was estimated at $100,000. Although UBC had the funds to build the Millennium Plug and conduct the necessary research, they did not have the funds for the portal reclamation required under the Mines Act; this shortfall led to UBC abandoning the project.

Although the 2200 Level concrete plug is sufficient to prevent discharge of acid mine drainage into Jane Creek and Britannia Creek, the UBC researchers believe it is not a permanent solution. With the exposure over time to the acidic waters that flow through the mine, this concrete plug will eventually fail after about 60–70 years of service. However, the Provincial government's engineering consultants advised that sampling of the water behind the 2200 plug before removal of the sampling valve, showed the water that the chemistry behind the plug had become more neutral with respect to sulphate levels and pH since construction of the plug, and therefore the simple concrete plug could last much longer than 60–70 years. UBC researchers believe this is likely speculative as the extremely high sulphate concentrations even at neutral pH levels observed before the plug was constructed, will likely return and result in degradation of the concrete plug, similar to what is currently being experienced at the Capilano reservoir tunnels which are being replaced after 70 years of service life.

The plug effectively diverted acid mine drainage to flow with the remaining ARD to discharge untreated from the 4100 portal into a deep outfall pipe into Howe Sound, resulting in lesser impact, but still substantially affecting the aquatic ecosystem in Howe Sound. Field monitoring done in 2003, using intertidal algae and mussels as ecological indicators, showed that the recovery of coastal biological communities was actually minimal.[8] However, recovery of Britannia Creek was significant and the amount of copper and zinc in the total discharge waters declined by about 20%.

As part of the reclamation work undertaken by the Provincial government, an environmental monitoring program is under way to determine the recovery of Britannia Creek and Howe Sound subsequent to the 2200 plug diversion (2001 by UBC), startup of the water plant (2005 by the Provincial Government), startup of the groundwater management system and optimization (2005-2008 by the Provincial Government), and other reclamation activities (2003-2010 by the Provincial Government). Initial assessments show significant recovery, however, the Provincial government has not yet completed its comprehensive environmental impact assessment to confirm this conclusion.[9]

Following completion of the Water Treatment Plant it was estimated that 90% of the pollution to Howe Sound had been stopped. Optimization of the groundwater management system by 2008, further increased the reduction to 98-99%.[9] In 2011, pink salmon returned to Britannia Creek for the first time in over a century.

Among other positive developments, in 2015, the Provincial government turned its attention to the potential to decommission the 7 dams that exist in the upper parts of the Britannia Creek watershed and which use to be part of the mine site’s electricity generating infrastructure. These dams, close to a century old, have outlived their usefulness and are beyond repair. Their removal would have public safety benefits but the dismantling of some of these old structures would also have environmental benefits in terms of resident fish passage and habitat connectivity. The idea of removing some of these structures over time , especially the Tunnel Dam, was first broached in 2001 in a report overseen by Mark Angelo and the Outdoor Recreation Council and written by Rod and Laurie Stott entitled, River Recovery.

References

- ↑ Britannia Mines Concentrator. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Akrigg, G.P.V.; Akrigg, Helen B. (1969), 1001 British Columbia Place Names (3rd, 1973 ed.), Vancouver: Discovery Press

- ↑ Walbran, Captain John T. (1971), British Columbia Place Names, Their Origin and History (Facsimile reprint of 1909 ed.), Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, ISBN 0-88894-143-9

- ↑ http://www.seatoskycommunity.org/archived/britanniabeach/disaster/1915slide.html

- ↑ http://www.seatoskycommunity.org/archived/britanniabeach/disaster/1921fire.html

- ↑ http://www.seatoskycommunity.org/archived/britanniabeach/disaster/1921flood.html

- ↑ http://www.bcmm.ca/history/the_mill.html

- ↑ Zis, T.; Ronningen, V.; Scrosati, R. (2004), Minor improvement for intertidal seaweeds and invertebrates after acid mine drainage diversion at Britannia Beach, Pacific Canada, Marine Pollution Bulletin, Vol. 48, pp. 1040–1047

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 http://www.britanniamine.ca

Bibliography

Province of BC Britannia Mine Remediation Project: www.britanniamine.ca

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Britannia Beach. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lions Bay-Britannia Beach. |

- Portal To Britannia Beach

- Britannia Mine Museum

- Britannia Mine's Mill No. 3 National Historic Site

- Province of BC Britannia Mine Remediation Project

Other sources

Coordinates: 49°38′N 123°11′W / 49.633°N 123.183°W

| ||||||||||||||||||