Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot, BWV 39

| Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot | |

|---|---|

| BWV 39 | |

| Church cantata by J. S. Bach | |

|

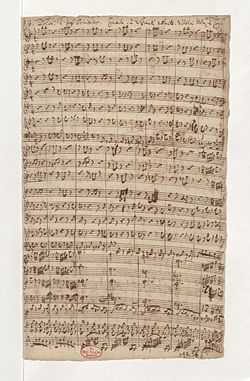

Opening orchestral Sinfonia from Bach's autograph score | |

| Occasion | First Sunday after Trinity |

| Performed | 23 June 1726 – Leipzig |

| Movements | 7 in two parts (3 + 4) |

| Cantata text | anonymous |

| Bible text | |

| Chorale | by David Denicke |

| Vocal |

|

| Instrumental | |

Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot (Break your bread for the hungry),[1] BWV 39, is a church cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach. He composed it in Leipzig and first performed it on 23 June 1726, the first Sunday after Trinity. About three years earlier, on the first Sunday after Trinity of 1723, Bach had taken office as Thomaskantor and started his first cycle of cantatas for the occasions of the liturgical year, and on the first Sunday after Trinity 1724 he began his second cycle, consisting of chorale cantatas. As he composed no new work for the first Sunday after Trinity 1725, Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot is regarded as part of his third cantata cycle.

The text is from a 1704 collection attributed to Duke Ernst Ludwig von Sachsen-Meiningen. The symmetrical structure of seven movements is typical for this collection, beginning with a quotation from the Old Testament, culminating in a central quotation from the New Testament and ending with a chorale. The theme is an invocation to be grateful for God's gifts and to share them with the needy.

Bach set the opening movement as a complex choral structure, but the central movement as a simple solo for the bass voice, traditionally considered the voice of Jesus. The instrumentation is for woodwinds and strings, including recorders as a symbol of poverty, need and humility. It is possibly the last time that Bach scored recorders in his cantatas.

History and text

Bach composed the cantata for the first Sunday after Trinity.[2] This Sunday marks the beginning of the second half of the liturgical year, "in which core issues of faith and doctrine are explored".[3] Bach had taken office as Thomaskantor in Leipzig on that occasion in 1723, responsible for the education of the Thomanerchor, performances in the regular services in the main churches of the town including Thomaskirche and the Nikolaikirche.[2] He had started the project of composing one cantata for each Sunday and holiday of the liturgical year,[3] termed by Christoph Wolff "an artistic undertaking on the largest scale".[4] In 1724 he started a project on the first Sunday after Trinity to exclusively compose chorale cantatas, based on the main Lutheran hymn for the respective occasion.[3] After two years of regular cantata composition, Bach performed a cantata by his relative Johann Ludwig Bach for the first Sunday after Trinity in 1725, and it was not until one year later, at the start of his fourth year in the office, that he composed Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot for the occasion.[5]

The prescribed readings for the Sunday were from the First Epistle of John, (the "God is Love" verses, 1 John 4:16–21), and from the Gospel of Luke (the parable of the Rich man and Lazarus, Luke 16:19–31). While Bach's first cantata for the occasion, Die Elenden sollen essen, BWV 75 (1723), had concentrated on the contrast of rich and poor, and his second one, the chorale cantata O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort, BWV 20 (1724), had reflected on repentance, the theme of Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot was to be grateful for God's gifts and share them with the needy.[2]

According to Christoph Wolff and Klaus Hofmann, the cantata text is taken from a 1704 collection which is attributed to Duke Ernst Ludwig von Sachsen-Meiningen.[5][6] Works from this collection had been set to music by the court composer Johann Ludwig Bach, whose cantatas Bach had frequently performed in 1725. They all start with an Old Testament quotation, then focus on a New Testament passage in a central movement.[6] The librettist organized the text in seven poetic movements, divided into two distinct parts. Both parts begin with a quotation from the Bible, but not, as in several other Bach cantatas, taken from the prescribed readings. Part I starts with a quotation from the Book of Isaiah (Isaiah 58:7–8), Part II begins with a quotation from the Epistle to the Hebrews (Hebrews 13:16), which forms the text for the central fourth movement. The first part derives from the words of the prophet a call to love one's neighbour and to share God's gifts, the second part similarly deals with thanks for God's gifts and makes a promise to love one's neighbour and share. The poet closed the cantata with stanza 6 from David Denicke's hymn "Kommt, laßt euch den Herren lehren" (1648),[7] which summarizes the ideas.[2] This hymn is sung to the melody of "Freu dich sehr, o meine Seele", which was codified by Louis Bourgeois when setting the Geneva Psalm 42 in his collection of Psaumes octante trios de David (Geneva, 1551). Bourgeois seems to have been influenced by the secular song "Ne l'oseray je dire" contained in the Manuscrit de Bayeux published around 1510.[8][9]

Bach first performed the cantata on 23 June 1726.[10] It is considered to be part of Bach's third annual cantata cycle in Leipzig. While the first and second cycle lasted one year, according to Christoph Wolff, the cantatas of the third cycle date from a period beginning on the first Sunday after Trinity, 3 June 1725, and lasting for about three years.[5] Musicologist Julian Mincham notes that "Bach attached personal significance to this particular day and consequently sought to parade a work of considerable substance".[11]

Scoring and structure

The cantata is scored for three vocal soloists (soprano, alto and bass), a four-part choir, two alto recorders, two oboes, two violins, viola, and basso continuo.[10] The recorders (flauti dolci) represent poverty, need and a "mood of humility". It is possibly the last time that Bach scored recorders in his cantatas.[12]

The cantata in seven movements is divided in two parts, to be performed before and after the sermon:

- Part I

- Chorus: Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot

- Recitative (bass): Der reiche Gott

- Aria (alto): Seinem Schöpfer noch auf Erden

- Part II

- Bass solo: Wohlzutun und mitzuteilen vergesset nicht

- Aria (soprano): Höchster, was ich habe

- Recitative (alto): Wie soll ich dir, o Herr

- Chorale: Selig sind, die aus Erbarmen

Music

The cantata is symmetrically centred around the fourth movement on the words from the New Testament. Movements 1 and 7 are choral, movements 2 and 6 recitatives, 3 and 5 arias in two sections each, neither utilizing the da capo form.[2]

The Old Testament text of the first movement is long and "multifaceted".[2] The opening chorus follows these words in a complex architecture of three sections, the first and the third section further composed of three parts.[2] The first section begins with a two-part ritornello and climaxes in a fugal exposition in all four voices. The second section starts with the shift to common time; it is characterized by a full texture and fluid melody. The chorus then returns to triple meter for the final section, which includes two four-part fugati.[11] The movement combines elements of the motet which follows the text, with composition in polyphony, elaborating on its different ideas.[2] Seth Lachterman explains the beginning of the movement:

The text of the movement is a paraphrase of Isaiah 58:7–8 in which the giving of food, shelter, and clothing to the needy is seen as a divine, transforming act of charity ... The first section ... literally depicts the distribution of bread to the hungry by 'distributing' staccato chords to differing musical forces (recorders, oboes, then strings).[12]

John Eliot Gardiner, who conducted the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage with the Monteverdi Choir in 2000, notes: "The opening chorus is multi-sectional and, at 218 bars, immense". He continues:

After ninety-three bars the time signature changes to common time: the basses begin unaccompanied, and are then answered by all voices and instruments very much in the old style of Bach's Weimar cantatas, with a florid counter-subject to suggest the 'clothing' of the naked. At bar 106 the time changes of 3/8 (again a Weimar feature) and the tenors lead off in the first of two fugal expositions separated by an interlude with a coda. The sense of relief after the stifling pathos of the opening sections is palpable and comes to a sizzling homophonic conclusion with 'und deine Besserung wird schnell wachsen' ('and thy health shall spring forth speedily'). The basses now instigate the second fugal exposition, 'the glory of the Lord shall be thy reward'. After so much pathos, the final coda led by the sopranos 'und die Herrlichkeit des Herrn wird dich zu sich nehmen' releases the pent-up energy in an explosion of joy.[3]

A secco bass recitative leads into the alto aria with obbligato oboe and violin that concludes Part I. The aria conveys three main images: "imitation, ultimate celestial ecstasy, and the scattering of fertile seeds".[11]

The fourth movement is sung by the bass, the vox Christi (voice of Jesus), as if Jesus said the words himself which Paul wrote to the Hebrews: "Wohlzutun und mitzuteilen vergesset nicht" (To do good and to communicate forget not).[1][3] The style is typical for Bach's treatment of such words, between arioso and aria.[2] The accompaniment is asymmetrical and repetitive, almost a ground bass.[11]

The soprano aria is accompanied by two unison obbligato recorders. The ritornello is simple and fluid, while the vocal line "has, at times, the quality of a folk song". The penultimate movement, an alto recitative, is accompanied by dense chordal strings.[11]

The closing choral, "Selig sind, die aus Erbarmen" (Blessed are those who, out of mercy)[1] is a four-part setting, "symmetrical and predictable until the last two phrases" of two-and-a-half measures each.[11]

Gardiner summarizes that all later movements are "dwarfed by the immensity, vigour, flexibility and imagination of the opening chorus, every phrase of its text translated into music of superb quality".[3]

Selected recordings

- J.S. Bach: Cantatas BWV 39, BWV 79, Fritz Lehmann, Berliner Motettenchor, Berliner Philharmoniker, Gunthild Weber, Lore Fischer, Hermann Schey, Archiv Produktion 1952

- J.S. Bach: Cantatas BWV 32 & BWV 39, Wolfgang Gönnenwein, Süddeutscher Madrigalchor, Consortium Musicum, Edith Mathis, Sybil Michelow, Franz Crass, EMI late 1960s?

- Kodaly: Harry-Janos Suite for Orchestra; Bach: Cantata Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot BWV 39, Diethard Hellmann, Bachchor und Bachorchester Mainz, Nobuko Gamo-Yamamoto, Martha Kessler, Jakob Stämpfli, SWF late 1960s?

- Les Grandes Cantates de J.S. Bach Vol. 28, Fritz Werner, Heinrich-Schütz-Chor Heilbronn, Württembergisches Kammerorchester Heilbronn, Ingeborg Reichelt, Barbara Scherler, Bruce Abel, Erato 1973

- Bach Cantatas Vol. 3 – Ascension Day, Whitsun, Trinity, Karl Richter, Münchener Bach-Chor, Münchener Bach-Orchester, Edith Mathis, Anna Reynolds, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Archiv Produktion 1975

- J.S. Bach: Das Kantatenwerk – Sacred Cantatas Vol. 3, Gustav Leonhardt, Knabenchor Hannover, Leonhardt-Consort, René Jacobs, Max van Egmond, Teldec 1975

- Die Bach Kantate Vol. 40, Helmuth Rilling, Gächinger Kantorei, Bach-Collegium Stuttgart, Arleen Augér, Gabriele Schreckenbach, Franz Gerihsen, Hänssler 1982

- J.S. Bach: Cantatas, Philippe Herreweghe, Collegium Vocale Gent, Agnès Mellon, Charles Brett, Peter Kooy, Virgin Classics 1991

- Bach Edition Vol. 19 – Cantatas Vol. 10, Pieter Jan Leusink, Holland Boys Choir, Netherlands Bach Collegium, Ruth Holton, Sytse Buwalda, Bas Ramselaar, Brilliant Classics 2000

- Bach Cantatas Vol. 1: City of London, John Eliot Gardiner, Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Gillian Keith, Wilke te Brummelstroete, Dietrich Henschel , Soli Deo Gloria 2000

- J.S. Bach: Cantatas for the First and Second Sundays After Trinity, Craig Smith, Emmanuel Music, Jayne West, Pamela Dellal, Mark McSweeney, Koch International 2001

- J.S. Bach: Complete Cantatas Vol. 16, Ton Koopman, Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir, Johannette Zomer, Bogna Bartosz, Klaus Mertens, Antoine Marchand 2002

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Dellal, Pamela. "BWV 39 – "Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot"". Emmanuel Music. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8

- Dürr, Alfred (2006). The cantatas of J. S. Bach. Oxford University Press. pp. 392–397. ISBN 0-19-929776-2.

- Dürr, Alfred (1981). Die Kantaten von Johann Sebastian Bach (in German) 1 (4 ed.). Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag. pp. 333–336. ISBN 3-423-04080-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Gardiner, John Eliot (2004). "Cantatas for the First Sunday after Trinity / St Giles Cripplegate, London" (PDF). bach-cantatas.com. p. 5. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ↑ Wolff, Christoph (1991). Bach: Essays on his Life and Music. Harvard University Press. p. 30.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Wolff, Christoph (2002). Bach's Third Yearly Cycle of Cantatas (1725–1727) – I (PDF). pp. 7, 9. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hofmann, Klaus (2009). "Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot, BWV 39 / To deal thy bread to the hungry" (PDF). bach-cantatas.com. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ "Kommt, laßt euch den Herren lehren". bach-cantatas.com. 2005. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ Gérold, Théodore, ed. (1921). "Chanson XVII: Ne l'oseray je dire". Le manuscrit de Bayeux: texte et musique d'un recueil de chansons du XVe siècle (in French). Strasbourg: Librairie Istra. p. 18. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "Freu dich sehr, o meine Seele". bach-cantatas.com. 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot BWV 39; BC A 96". Leipzig University. 1967. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Mincham, Julian (2010). "Chapter 17 BWV 39 Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot". jsbachcantatas.com. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lachterman, Seth (2000). "Program Notes: Nov. 2000 Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot". berkshirebach.org. p. 39. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

Sources

- Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot, BWV 39: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- "Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot BWV 39; BC A 96 / Cantata". Leipzig University. 1967. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Cantata BWV 39 Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot: history, scoring, sources for text and music, translations to various languages, discography, discussion, Bach Cantatas Website

- Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot: history, scoring, Bach website (German)

- BWV 39 Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot: English translation, University of Vermont

- BWV 39 Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot: text, scoring, University of Alberta

- Cantata No. 39, "Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot," BWV 39 (BC A96), Allmusic

| ||||||||||

|