Briarcliff Farms

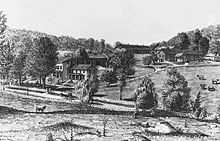

Briarcliff Farms was a farm established in 1890 by Walter William Law in Briarcliff Manor, a village in Westchester County, New York. One of several companies founded by Law in the turn of the 20th century, Briarcliff Farms was known for its milk, butter, and cream; its operations also produced other dairy products, American Beauty roses, bottled water, and print media. At its height, the farm was one of the largest dairy operations in the Northeastern United States, operating about 8,000 acres (10 sq mi) and maintaining over 1,000 Jersey cattle. In 1907, the farm moved to Pine Plains in New York's Dutchess County, and it was purchased by New York banker Oakleigh Thorne in 1918, who developed it into an Angus cattle farm. After Thorne's death in 1948, the farm changed hands multiple times; in 1968 the farm became a beef feeding operation named Stockbriar Farm. Stockbriar sold the farmland to its current owners in 1979.

The farm combined a practical American business model with the concept of a European country seat,[2] with cows being milked constantly, and with milk promptly chilled and bottled within five minutes, and then shipped to stores in New York City each night. The farm was progressive, with sterile conditions within all of its operations, numerous employee benefits, good living conditions for livestock, as well as regular veterinary inspections to maintain a healthy herd. The farm also made use of tenant farming, established working blacksmith, wheelwright, and harness shops on-site, was located around Walter Law's manor house, and constructed numerous buildings in the Tudor Revival architectural style.

The farm was the first location for the School of Practical Agriculture and Horticulture, established by the New York State Committee for the Promotion of Agriculture in conjunction with Walter Law. The function of the school was to educate people in farming, gardening, and poultry-keeping, among other agriculture-related skills. The school moved to a farm near Poughkeepsie in 1903, and the school building was run as a hotel for two years until it became Miss Knox's School. After the building burned down in 1912, Miss Knox's School was relocated several times; since 1954, the Knox School has been located at St. James, New York.

Locations

Briarcliff Manor

The farm was first established in the hamlet of Whitson's Corners (present-day Briarcliff Manor), 27 miles (40 km) from Manhattan in New York City. The farm overlooked the Hudson River, and was located between the Hudson and Pocantico Rivers. The farm's location was described in 1901 as "the most healthy, hilly portion of Westchester...where there are neither swamps nor contaminated streams of water".[5](p101) The initial land plot was four miles (6,400 m) long and three miles (4,800 m) wide, and was developed inside of twelve years.[6] In 1901, Briarcliff Farms (including its school farm) encompassed 6,000 acres (9 sq mi) in the area between Pleasantville and Old Briarcliff Roads north of Scarborough Road,[7](p31) At its peak, the farm's original location encompassed 7,800 acres (10 sq mi) of land.[8] In Briarcliff Manor, the farm had six main barns: Barn A near the farm's office building on Pleasantville Road, which housed all of the horses for the farm and for the Briarcliff Lodge.[9](p23) The farm's blacksmith, wheelwright, and harness shops and other buildings were located around that barn; the farm also had a smokehouse and butcher's shop on-site.[10](p336) Barns B (housing 78 cattle) and C (housing 118 cattle) were at the south end of Dalmeny Road,[1](p23) and Barn D (housing 116 cattle) was between Beech Hill Road and New York Route 117; it later was used as a boarding stable for horses. Barn E held 118 cattle and was on Pleasantville Road just east of the present Taconic State Parkway, and Barn F (housing 118 cattle[4](p24)) was in Millwood near a crossing of the Taconic and New York Route 100. The farm also had a large barn near New York Route 9A for supplies, including all of the feed for the farm. The barns each had ice sheds to cool the milk, and ice was primarily harvested from Echo Lake (source of the Pocantico River), with Kinderogen Lake (now part of the Edith Macy Conference Center) as a supplemental source.[7](p35) The farm also had a large supply store that housed feed amd other items, southeast of the service station on North State and Pleasantville Roads.[4](p27)

The farm office was also the first dairy building,[11] and held Walter Law's personal office. The building burned down in 1901 and was rebuilt in 1902. Between the village's 1902 incorporation and the construction of its first municipal building in 1913, the building also held Briarcliff Manor's village government.[3] In the 1960s, the building was redesigned and rebuilt and became a local union headquarters within the International Union of Operating Engineers.[1](pp16, 126) The farm was enclosed and its pastures were divided[12] by stone walls taken from within the farmland;[13] those stones were also used for roadbeds, walls of the farm buildings and office, and Law's house.[10](p336)[11](p307)

Walter Law encouraged his employees at Briarcliff Farms to move into the village, and he sold plots of land either of 2,500 square feet (230 m2) or 11,250 square feet (1,045 m2) to any worker at a nominal price. He would then ask the worker to choose what kind of house he wanted, and then Law would have it built and take a mortgage on it;[13] Law also allowed workers to rent a cottage.[10](p335) In that way, Law built several wood-framed cottages near the farms,[1](p23) which all had a steep front-gable roofs and open porches using up some of the first floor space.[14] Of the cottages still standing, six are on Dalmeny Road and three are on Old Briarcliff Road.[1](p125) The farm also owned and operated a farm in Peekskill that had previously been owned by John Paulding, a militiaman who helped capture British Major John André.[15](pp29–30) Briarcliff Farms ran the Peekskill farm as a nursery to grow maples, oaks, lindens, hemlocks, spruces, and other trees.[16](p587) In the early 1900s, Law also purchased farms in Lewisboro and Pound Ridge, and he used those farms to breed cattle to replenish the farm's herd. He also purchased a house in Pound Ridge which his Briarcliff Realty Company sold to Westchester County after his death; it then became headquarters of the Ward Pound Ridge Reservation, the county's largest park.[17]

Dalmeny

Law provided Dalmeny, a boarding house on Dalmeny Road[1](p36) for the farm's single men.[6] The building, modeled after the Mills Hotels in New York City,[18] was 100 feet (30 m) long and four stories tall. Its first floor held a social hall for meetings and entertainment; a parlor and reading room equipped with books, newspapers, magazines, and games; a large dining room; a private dining room; a kitchen; and a bathroom with marble basins and supplied with clean towels. The upper floors held seventy individual bedrooms for the men and unrestricted access to bathrooms with showers and tubs on every floor.[13][19] Dalmeny also housed a barber who would trim hair for the residents. None of the farm workers were required to be housed at Dalmeny, although the building was so well-kept that the number of people who wanted to live there exceeded the available space. The cost was 15 to 18 dollars per month, including room, board, and laundry. Walter Law frequently joined the men at meals,[13] known lecturers frequently visited the boarding house to speak,[11](p313) and the farm workers had their own orchestra, brass band, and glee club that gave shows at the boarding house.[10](p335)[18]

Dalmeny first opened on Christmas in 1899,[19] and closed in July 1908, in conjunction with the relocation of the farm to Upstate New York.[20](p142) In 1909, the building was moved over a period of months to the Briarcliff Lodge property, where it stood adjacent to the Lodge's laundry building.[nb 1] When the Lodge was used as the campus of The King's College (from 1955 to 1994), the school referred to the former boarding house as Harmony Hall, and used it for classrooms and staff housing.[1](pp36, 90) In autumn 1979, the college demolished the building shortly after dedicating a new classroom building.[1](p90)

Pine Plains

The farm's second location, in the town of Pine Plains, was initially 3,249 acres (5 sq mi) in size.[21] The farm was 2 miles (3 km) from the hamlet of Pine Plains and was adjacent to the Central New England Railway.[22] The farm was located in the shallow Stissing Basin, 12 miles (20 km) from the Hudson River.[20](p105) In Pine Plains, the farm had three barns, each housing 200 Jersey cattle (with beds of sawdust or shavings[22]) which were built at a cost of about $20,000 each ($525,000 today[23]). Barn B was in Pine Plains' hamlet of Bethel,[21][22] and Barn C was farther south, in the town of Stanford.[21]

Operations

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Sugars |

4.83 g |

|

5.36 g | |

|

3.76 g | |

| Other constituents | |

| Water | 85.31 g |

|

Source: "The Inspiration of a Great Farm", Country Life in America, page 13, 1902.[6] | |

| |

| Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

| Briarcliff Farms herd population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | No. | ±% p.a. |

| 1893 | 330 | — |

| 1899 | 849 | +17.06% |

| 1900 | 1,029 | +21.20% |

| 1901 | 1,045 | +1.55% |

| 1902 | 1,100 | +5.26% |

| 1904 | 2,460 | +49.54% |

| 1915 | 900 | −8.74% |

| 1918 | 1,000 | +3.57% |

| Sources: | ||

The farm was one of the first producers of certified milk in the U.S., having begun around 1901 and under the supervision of the Milk Commission of the Medical Society of the County of New York.[22] With the farm's cattle producing about 4,500 US quarts (4,300 litres) of milk daily,[13] (with an average of 8 US quarts (7.6 litres) per cow per day[22]) Briarcliff Farms was one of the largest dairy operations in the Northeast.[8] According to Nebraska's department of agriculture in 1903, the three largest owners of dairy cows in the US eastern states were Fairfield Farm Dairy in New Jersey, Briarcliff Farms, and the Walker-Gordon Laboratory Company, which had "branches in all of the principal cities".[28] In 1897, the farm kept Jersey, Normande, and Simmental cattle,[12] and sold those breeds' milk at 10, 12, and 15 cents per quart respectively. The farm also sold cream (of 50% butter fat[13]) at 60 cents per quart, as well as Jersey butter at 50 cents per pound, and Normande or Simmental butter at 60 cents per pound.[29] In 1909, half of the farm's herd consisted of registered Jerseys, and the other half were high-grade Jerseys.[22] In Pine Plains, many of Barn B's milkers were from the Netherlands due to its reputation for the best milkers.[21]

In 1905, farm workers were milking nearly 500 cows at any given moment. The farm raised its own stock and fed the cattle eight pounds of dry feed twice daily,[22] with pasture and green corn in summer. The feed mixture was 50 percent bran, 25 percent crushed oats, and 25 percent cornmeal; all of which were claimed to be the best quality available on the market. The farm would require that cattle produce 6,000 pounds of milk with 5 percent butterfat or 5,000 pounds of milk with 6 percent butterfat; otherwise the cow would be butchered or sold. The average grain consumed by the cows was 7 pounds per day; 2 when on pastures and 12 in winter; each cow was also fed 1.5 to 2 pounds of oil meal each day and all the hay (timothy and clover) the cow could eat (17-20 lbs. daily, depending on the animal's size). Each farm worker milked, cleaned, and groomed 16 to 18 cattle daily, taking up about all of their time. The New York Milk Commission analyzed the farm's milk weekly; the board of health regulations in New York permitted as high as 3 million bacteria per cubic centimeter in milk; the milk commission limited bacteria to 30,000. The farm chilled its milk almost immediately after milking (within 2 minutes), and the milk would be chilled to 45 degrees Fahrenheit; often limiting bacteria counts to 200 to 400 bacteria per cc.[30](pp289–91) The farm also had a chemical analysis of the milk performed every month;[31] regulations required a minimum of 3 percent fat in milk. Briarcliff milk was required to contain over 5 percent fat, otherwise the milk was not offered for sale.[13] In March 1905, the New York Milk Commission analyzed that the farm's milk had 8.2 percent milk fat, which was publicized as the farm's "richest Briarcliff product ever reported on".[32](p210)

In 1901, the farm had 1,045 Jersey cattle, 4,000 chickens and ducks, 1,500 pigs, and 400 sheep.[13][25](p2666) Later it would grow to have 500 workers tending those animals in addition to Thoroughbred horses, pheasants, and peacocks.[33] The pigs, which included Chester Whites and Berkshires, were constantly outdoors; the farm superintendent believed the animals should only be in pens for breeding purposes. In summer, the pigs were allowed to run in the orchards or the woods.[13] Approximately 2,000 were slaughtered each year.[10](p336) The farm's 31 poultry houses were run by a head poulterer and 40 assistants; each building was 18 by 100 feet, and the buildings were spread out on the property. The farm would use 300-egg insulators,[10](p336) and feed the hens five times a day with a mix of grains including oats, wheat, and corn.[13] The farm butchered 7,000 broilers each season[34] Eggs sold at 35 to 50 cents per dozen and there was a much larger demand than supply. Broilers sold from $1.50 ($43 today[23]) to $3.00 ($85 today[23]) per pair.[13] The farm also raised about 300 lambs each spring, primarily Dorset Horns. The lambs were all dressed (their internal organs removed) on the farm, after which they would be sold for $12 ($340 today[23]) or more each; there was also a greater demand for lambs than the available supply.[10](p336)[13]

The farm's gardens grew a variety of crops, adapting to the market;[34] in 1900 the gardens' crops included oats, rye, corn, wheat, buckwheat, carrots, mangolds, turnips, rutabagas, radishes, sugar beets, potatoes, apples, cabbages, rye straw, oat straw, hay, wheat straw, corn stalks, and ensilage.[2] The farm also rotated grain production in order to grow better vegetables. At one time, the farm had 12 acres (0.02 sq mi) planted solely of asparagus,[13] sold at 35 to 50 cents per bunch.[10](p334)

The farm also operated a printing press and office north of the farms office on Pleasantville Road. The print shop produced various print media, including Briarcliff Farms, the Briarcliff Bulletin in 1900, the monthly Briarcliff Outlook in 1903 followed by The Briarcliff Once-a-Week in 1908 (all edited by Arthur W. Emerson).[9](p27) The print shop also printed bottle caps for Briarcliff dairy products. The Briarcliff Table Water Company sold its products in New York City, Lakewood, New Jersey, and the Westchester municipalities Yonkers, Tarrytown, White Plains, and Ossining. The company owned 250-foot (76 m) wells.[4](p27) Around 1901, the Briarcliff Steamer Company No. 1 (later the Briarcliff Manor Fire Department) housed its equipment and horses at the Briarcliff Farms' Barn A.[35](p5) The American Plasmon Syndicate, a producer of the dried milk product plasmon, had their factory in Briarcliff in order to have milk directly sourced from Briarcliff Farms.[36] The farm had built the factory as well as an electric plant for its needs.[37]

In a 1900 publication, the farm's motto was reported to be "The production of pure food of the highest standard of excellence",[38] although a 1902 publication stated the farm's motto was "Do unto a cow as you would that a cow would do unto you", and also mentioned that the phrase was placed in large letters in every barn on the farm.[11](p309) Similarly, notices printed by the farm would begin with the verse "If a Cobbler by trade, I'll make it my pride, the best of all Cobblers to be; and if only a Tinker, no Tinker on earth shall mend an old Kettle like me".[13] At the boarding house Dalmeny, this verse among several other mottoes were printed on friezes on the interior walls of the building.[2][9](p67)

Processing and delivery

At its peak, the farm delivered milk to areas between and including Albany and New York City.[8] After cooling, milk was brought daily to the dairy processing building.[39] When milk was brought into the building, it would be poured into a large sterilized tank and then forced, using compressed air at 160 US quarts (150,000 ml) per minute,[11](p312) through sterilized pipes to the building's second floor. There the milk would be cooled, strained five times, and then bottled.[13] The milk then would be sealed with parchment circles with the certification of the supervising commission and the date,[22] and then would be put in boxes with ice.[31] The whole process from entering the building to bottling took five minutes. Every utensil that contacted the milk or workers would be regularly sterilized using live steam. The building was free of bacteria as best as the farm could make it; its rooms had white-tiled walls and floors, with coving (concave tiling) between the walls and floors for better cleaning.[13] Milk bottles would be reused; the farm's machines cleaned them with rotating wire brushes several times and then heat-sterilized them for two hours.[31]

The farm's products would be packaged as milk, cream, butter, or kumyss, and sent every night via the New York and Putnam Railroad to New York City for delivery on the following day;[9](p26)[39] it would be sold to the public in the farm's stores or from their wagons.[11](p312) The farm had three stores in New York City and one in Greenwich, Connecticut; in Westchester, the farm had a store in Yonkers, Dobbs Ferry, and Tarrytown.[40] The farm's first New York City store was in Manhattan's Windsor Arcade, at Fifth Avenue and 46th Street; the farm also had an office in the Seymour Building, at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street.[41] The office created advertisements that were used in the New-York Tribune, New York Times, New York Evening Post, and Mail and Express, what Printers' Ink said was obviously advertising to wealthy city residents.[41] The stores sold Briarcliff dairy products in addition to Briarcliff table water.[1](p36) Milk was also sent to Hotel Lorraine, the St. Regis Hotel, the Waldorf Astoria, Mendel's Lunch Room at Grand Central Station [sic], and Milhau's Drug Store on Broadway; kumyss was sent to seventeen New York City drugstores. Milk was sold to stores in New York free on board for $0.084 ($2.13 today[23]) per quart.[22] The farm also supplied the Briarcliff Lodge with cream, milk, butter, eggs, and vegetables;[42] it also shipped its products on steamers across the ocean in zinc-lined cases, and shipped to all US locations every day except Sunday, and would ship a double order on Saturday to make up for Sunday.[39](p278) In Pine Plains, the farm's milk was processed into milk, cheese, butter, or buttermilk at its creamery at Barn A, and was then packaged for the 101-mile (200 km) railroad shipment to New York City.[21]

Ethics and advances

That a man...who has acquired wealth by trade or manufacture should leave the city to develop an ideal farm is something new and notable. This is what Mr. Walter W. Law has done at Briarcliff Manor. He determined to have a farm run absolutely on the highest principles—a farm where science should speak the first word and the last word, and all the time. Science is nothing but accumulated experience; what we have found out to be best and truest; and so Briarcliff Manor farms were simply to do the best, instead of second best, or third best, or tenth best. The houses were to be models, the stables were to be ideal, the orchards planted and worked ideally, the gardens must show what possibly could be done in vegetables, and the corn crop and the oats and the wheat must not be left to any guesses of man or nature. Feeding must be done on scientific principles; barns must be as sanitary as houses; stables must be sunny and thoroughly ventilated. Water must be absolutely pure for the cattle, and their sanitary conditions as perfect as those for human beings.

In 1906, Andrew Carnegie wrote of his impression of the farm, that "every known appliance or mode of treatment is at hand, and the herd is pronounced free from all and every ailment. In cases of doubt animals are sacrificed".[43] The farm ensured the best obtainable stock, extensive and expensive experimenting, for the products sent out. The operation set rich and abundant food, cleanliness, light, good air, and gentleness for the animals as high priorities. The farm also immediately removed every cow with indication of sickness, and a large number of cattle were slaughtered during the farm's first few years to better the overall health of the herd. In relation to that, Walter Law said "It is not the cows that have been put in, but those which have been taken out, that have made the Briarcliff herd what it is". The farm's large and light barns had concrete floors which were scrubbed every day.[31] The farm also had up-to-date appliances for separating, churning, handling, and packing its products.[6]

Every year, Law offered cash awards in September to be distributed at Christmas, given to workers for certain results,[2] including being the "most gentle with cows", the "most careful teamster in feeding his horses and keeping his stables clean", or for having the "cleanest delivery wagon", "neatest house yard", "best garden truck", or "best kept room in Dalmeny".[13] The farm gave an emphasis that virtues such as those have a commercial benefit. The prizes were all $5 ($142 today[23]), to be awarded by Law at Dalmeny on December 24. That night, after the Briarcliff Orchestra performed Handel's "Largo", Law talked of the farm's improvements that year and then of the prizes.[2] The Briarcliff Orchestra was made up of the farm's workers; among its members was Law's son Walter Jr.[13]

The arrangement for human beings must be on the highest level. Men and boys who were employed must be looked after to produce a splendid human result. That is, they must not be left to act as so many mechanical appliances or brute force masters of the lower animals...It seems not yet quite familiar to us that a store should have the Golden Rule for a business maxim; but what are we to make of a farm where the superintendent says, "Not until we apply the Golden Rule to cows will we ever get the best from them?" The walls of the stables are hung with such mottoes as "Speak gently; it is better far to rule by love than by fear." The application of this rule to cows ought to create a moral evolution in the stablemen, so that by and by it could be applied to human folk as well, and thoroughly believed in as a workable law of life.

The farm was a for-profit operation, and it intended to show that the best farming practices will pay off.[25](p2666) Walter Law believed that kind treatment would lead to better cattle, and thus the farm did not tolerate abuse of the cattle.[9](p26) Law had said "Cruelty to a cow is the same as cruelty to me, and shall never be permitted on this farm."[13] Similar to how Law knew every person living at the farms,[11](p316) the farm workers knew the names of the cows,[11](p310) which were also written on a brass plate at the head of each stall.[10](p336) Each cow was sponged several times a day, and the cattle were always combed before their milking. The workers would wear sterilized white cotton suits, which would be boiled clean every day, and Law treated and regarded his workers not as simple laborers, but as intelligent co-workers.[6] The cattle would be groomed before milking, and then a pail of warm water and a brush would be used on the cattle's sides, flanks, and udders; then the flank and udder would be thoroughly washed again with another pail of warm water containing about one percent of creolin, and a clean towel. More clean water and a towel would be used to remove the antiseptic. Next the cattle's udders would be thoroughly dried with fresh towels.[22] The workers would milk into a fine wire strainer placed over a pail; during the process, no talking, laughing, smoking, or spitting was permitted, as it was claimed to have a "perceptible effect upon their milk".[10](p336)[11](p312) The workers were required to thoroughly wash their hands after washing the udders and before milking each cow.[13] Every milker helped clean and wash the cattle, and each of them had a set of towels and washed, cared for, and milked 15 to 16 cows.[22] The farm also practiced that the cattle would graze from early spring until late autumn, and would never be in the barns except during milking. The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review stated in 1901 that it doubted any other large dairy near New York did this.[5](p102)

The farm also had a laboratory to regularly analyze the milk,[13] as well as a veterinary chemist. The farm's dairy plant had reception and visitor's observation room separated by glass doors to the different rooms,[10](p336) allowing view of every step of the farm's dairy processing operation. One room was for skimming cream, one for bottling milk, one for churning. The building's basement held its sterilizing, pasteurizing, and shipping departments. The facility shipped out 2,000 US quarts (1,900 l) of milk, 300 US quarts (280 l) of cream, and 500 pounds (230 kg) of butter each day.[44] Companies of trained nurses from leading New York City hospitals visited the farm to learn about its practices in relation to their work,[5](pp102–3) and students from the Ethical Culture School in the city visited; the Briarcliff Farms was reportedly chosen as the most typical industry of New York available for inspection.[45]

Greenhouse operations

Although the farm's primary operation was in dairy production, its secondary agricultural product was the American Beauty rose. The farm had two sets of greenhouses; one set behind Walter Law's house and directly west of the Briarcliff Lodge produced decorations for Briarcliff Farms, the Briarcliff Lodge, and Law's and his workers' houses. The other set, the Pierson commercial greenhouses, was used for growing the American Beauty rose and rare carnations, producing 22 varieties and about 2,500 blooms per day.[1](p26)[13] The greenhouses were advanced for their time, with light steel frames and unique glass panes for an "almost unshadowed exposure to the light". The newer greenhouses were 50 by 300 feet,[6] and each held up to 40,000 plants.[13] The roses earned the business up to $100,000 ($2.83 million today[23]) each year, and were sold in winter at 8 to 12 cents per piece;[13] most were shipped to New York City.[46] The Briarcliff Lodge ran an annual American Beauty carnival, with events including a golf tournament, water sports, moonlight bathing and night diving, a dinner dance, cinema program, and a concert.[47]

At the greenhouses, foreman George Romaine propagated an American Beauty with longer and more-pointed buds and a brighter color. Paul M. Pierson registered the rose with the American Rose Society as the Briarcliff Rose.[7](p37) The rose is Briarcliff Manor's village symbol,[48] and since 2006, an image of the rose has been used on village street signs.[49] The Briarcliff Manor Garden Club also uses the Briarcliff Rose as its symbol.[50] The Briarcliff Rose variety is now lost.[3]

School of Practical Agriculture

In the winter of 1895-96, the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor[51] made an inquiry into the causes for youth to move from the countryside into cities, and into the most efficient method of drawing back youth to the countryside.[nb 2] That, in addition to examining agricultural needs for a year[52] resulted in a meeting at the residences of Abram S. Hewitt and R. Fulton Cutting, and the group formed themselves into the New York State Committee for the Promotion of Agriculture.[6] The original committee was chaired by Hewitt, and also included Cutting, Jacob H. Schiff, John G. Carlisle, Mrs. Seth Low, Josephine Shaw Lowell, Walter Law, and William E. Dodge. The Board of Trustees had five officers, with Theodore L. Van Norden as president, and seventeen other trustees, including Law, V. Everit Macy, and James Speyer.[53] Professor[nb 3] George T. Powell, who The New York Times called a "recognized authority on scientific agriculture", was called in for consultation; he later undertook the school's organization and became the first and only director of the school.[53] Once Walter Law was called in, the school's definite plan took shape,[6] as Law provided the school property and building.[54] In September 1900,[34] Law and the committee established the School of Practical Agriculture and Horticulture as part of Briarcliff Farms, on an elevated site of 66 acres (0.1 sq mi), about midway between the Briarcliff Manor and Pleasantville train stations[55] on Pleasantville Road.[1](p10) Law had leased the 66 acres (which were worth $1,000 ($28,300 today[23]) an acre) for 20 years at a dollar a year; he also gave the trustees $30,000 ($850,400 today[23]) to build a dormitory, and he promised them $3,000 ($85,000 today[23]) a year for expenses until the school began to profit. With that and $30,000 from the trustees, the school opened.[13] The committee decided for the curriculum to focus on methods of horticulture, floriculture, gardening, and aviculture.[52] The school's progress was closely followed by members of the public interested in forms of agricultural education.[56]

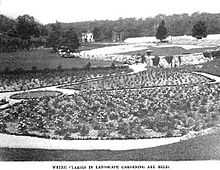

The School of Practical Agriculture was regarded as an experiment when established;[56] it had the object "to open an independent means of livelihood for young men and women, especially of our cities; to demonstrate that higher values may be obtained from land under intelligent management, and to develop a taste for rural life." Its students were trained in garden and farm operations over a general course of two years, although the school also offered short courses in nature study, which were held for a few weeks of summer. There were three terms each year, including twelve weeks' vacation; the school allowed new students to start at the beginning of any term, although a September start was the most desirable.[38] The school had courses or instruction in agriculture, horticulture, cold storage, botany, chemistry, geology, physics, agricultural zoology, entomology, apiculture,[38] meteorology, land surveying and leveling, soils, drainage, irrigation, tillage, fertilizers, plant diseases, stock, fruit growing, landscape gardening, and bookkeeping, all with specific reference to agriculture and horticulture. It was run as a practical school, with no attempt to give students a general education; practical work included care of orchard trees and bush fruits, culture of fruits and vegetables "under glass", making of jellies and jams, market-gardening, tillage of soils, use of fertilizers, hybridization and propagation of flowers, methods of harvesting and marketing crops. The school also made use of Briarcliff Farms, where students worked the farmland, tested the cattle's milk, and took care of all of the different animals.[34] As well, the students raised flowers, vegetables, and fruit, and would accompany their products to the cities, where they would assist in their marketing.[11](p314) The New York Botanical Garden arranged with the school to give the students access to its lectures, museums, and conservatories.[13] Tuition was $100 a year ($2,800 today[23]), and board was $280 a year ($7,900 today[23]). Instruction was primarily given in lectures, given at forenoon on weekdays; in the afternoon, students worked on the school farm under their instructors' supervision. Instruction also involved indoor laboratory work.[6] The school farm also had a foreman, gardener, and several workmen to ensure its continual operation.[56] 35 students attended in 1901 and 34 attended in 1902,[6] almost all from cities; their ages ranged from 16 to 35. Most of the students had high school education prior to enrollment, and some had college education as well. With 35 students, at the time the school was at its limit for accommodations, although plans to expand were mentioned.[56]

For a single year the school was held in the basement of Pleasantville's public school building, until its building at Briarcliff Farms was completed. During that time the school did not provide housing.[34] The school building was completed in spring 1901[1](p18) and opened and dedicated on May 15.[55] It was a large Colonial Revival building with a plain exterior and wide halls,[34] and it had lecture halls, a library, a laboratory,[6] an office, a dining hall,[55] and dormitory space for 40 staff members and students. The school grounds had an orchard, a working garden, greenhouses for experimenting, poultry houses, a farmhouse,[56] and barns.[25](p2666) The school's faculty included a director, a horticulturalist, an agriculturalist, and instructors in nature study and cold storage. The school was coeducational (the course did not differ for female students[34]), and students were required to have English proficiency, good references, be older than sixteen, and be in good health.[56] On January 1, 1902, Henry Francis du Pont, then in his third year at Harvard University, wrote to Powell requesting admission to the school. Powell replied that he had listed DuPont first for the school's 1903 class. DuPont was not able to attend the school, and ended up leaving Harvard, speculated to be because of his mother's sudden death in autumn 1902.[57]

Relocation and closing

The school had outgrown its Briarcliff location;[58] in autumn 1902, R. Fulton Cutting purchased a 415-acre (0.6 sq mi) farm near Poughkeepsie so the school could be permanently established upstate.[53] Before this move, the school was popularly known as the Briarcliff School; the school's name after its move would be "the School of Practical Agriculture at Poughkeepsie". When established, Van Norden expressed that the school needed funds for equipment and its endowment,[54] and the land still had no buildings; the school rented two houses in Poughkeepsie to hold the school until funds were acquired to build on the purchased land.[59] The school initially hoped to raise a million dollars,[58] but in 1903, after then endeavoring to collect $150,000 ($3.94 million today[23]), but only securing $50,000 ($1.31 million today[23]) to operate the school, Director George Powell announced that the school would be closed and the property sold. Cutting presented a plan to the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts to carry out the plan devised for the school in Poughkeepsie.[60] In 1908, school funds were donated to Cornell University as the Agricultural Student Loan Fund, for students in Cornell's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.[61]

From 1903 to 1905, the original school building was known as Pocantico Lodge, and was run as a small year-round hotel. In 1905, Alice Knox, an employee at Mrs. Dow's School, opened a school in the building which became known as Miss Knox's School. The building burned down in 1912, and the school moved to nearby Tarrytown and then to Cooperstown.[7](p38) Since 1954, the Knox School has been located at St. James, New York.[62] The only remaining feature of the building is a stone retaining wall in front of the current building, built in 1925 by Oscar Vatet for Reverend Dr. Rufus P. Johnston (pastor of John D. Rockefeller's Fifth Avenue Baptist Church). The building later became home to Dr. Arthur O'Connor; then to Cognitronics, and later to Frank B. Hall, Inc. It is currently an empty and unused part of Briarcliff Corporate Campus.[7](p71, 73)

History

James Stillman had owned a small farm on Pleasantville Road since at least 1886.[1](pp9, 12) Stillman's farm was named Briarcliff Farm after John David Ogilby's estate "Brier Cliff", itself named after Ogilby's family home in Ireland.[7](pp21, 31)[63] In 1887, Stillman exhibited a display at the Great Dairy and Cattle Show in New York City's Madison Square Garden, where he showed the processes of setting milk, churning cream, and making butter.[64] In 1890, Walter Law began purchasing property in the present-day village of Briarcliff Manor, as part of his desire for rest and recreation.[6] That year, Law paid James Stillman $35,000 ($918,700 today[23]) for his 236 acres (0.4 sq mi) farm; he altered his property's name to "Briarcliff Farms".[65] In 1893, The New York Times reported that the 14th Duke of Veragua (a stock farmer himself) along with a large party had visited the farm on the afternoon of June 16, 1893. At the time the farm had about 330 cattle and 100 sheep. The party went from New York to Scarborough, and then used numerous carriages to go to Briarcliff. In order, the party visited the farm's poultry yard, hennery, and stables. The group then viewed the farm's heifers and stallions and went to creamery to taste the Briarcliff butter. The guests went to Law's Yonkers home "Hillcrest" for dinner and then returned to New York. The duke had said "Well, this is a perfect place. I am delighted with what I have seen."[24]

In 1898, Law retired from vice presidency at W. & J. Sloane, moved with his family to the area, and began devoting his time to his farming.[7](p35) Law rapidly added to his property, buying about forty parcels in less than ten years; by 1900, he owned more than 5,000 acres (8 sq mi) of Westchester County,[46][66] and became the largest individual landholder in the county.[67] He made deals with some of the farms he purchased, where the previous owner would become a tenant farmer; e.g. Jesse Bishop's 160-acre (0.2 sq mi) farm, where Law agreed to receive half of the farm's hay and straw and a third of everything else.[7](p35) Early on, Law and Briarcliff Farms deepened the Pocantico River for a length of 2 miles (3 km), taking out the rifts so the stream would flow and the swamps adjacent to the river would drain. The workers also cut rock and took out trees that lined the swamps to reclaim land for farming.[2]

Law found that the soil was poor, having been used by farmers for the past fifty years. The fields were lacking in grass, and the cows yielded poor milk. Law said, "I had to begin at the bottom and repair the waste of fifty years." Law increased his soil's fertility by arranging for waste and manure in New York City streets and stables to be regularly transferred to his farm; for four years twenty car-loads of manure each week were used on the farmland. As a result of that effort, the farm's hay yield had grown from two to five tons. Law also decided to improve the area's roads, giving them a base layer of large, closely packed stones and further layers of top gravel. Law also developed his herd; at first the farm had weak cattle (many afflicted with tuberculosis) and "ordinary milk", and after Law's development, the farm had strong cattle, healthy calves and rich milk in abundance. Law hired Dr. Leonard Pearson, a professor of veterinary medicine at the University of Pennsylvania,[2][13] to examine each cow every 6 months for tuberculosis[5](p102) and other diseases, a standard above that of the New York City Board of Health.[6]

In the beginning Law had very little knowledge or experience in farming, but he had enough money to reach his goal of maximizing the dairy farm's quality and output.[43] Law's farm eventually grew to having 500 workers, cattle, pigs, chickens, Thoroughbred horses, pheasants, peacocks, and sheep, at the farm's peak.[33] In 1900, after the US government requested that the farm exhibit its milk, butter, and cream at Paris' Exposition Universelle,[37] Briarcliff Farms entered its products to be judged,[1](p23) and sent raw milk as well as pasteurized milk and sterilized milk, the French sent word that "there is no use sending these, for your fresh milk keeps fresh".[2] The farm contributed to the USDA's Bureau of Animal Industry and the New York State Commission to the Paris Exhibition's collective exhibit,[68] and won gold medals for its milk, cream, and butter[69] and a silver medal for social benefit or economy.[18][70] After concern that the milk had preservatives, the French authorities asked for a sworn affidavit that no chemicals were added, which the farm sent.[37] In addition, the farm was photographed by the US government for display at the exposition.[44] The photographs, of the barns, farmland, Law's mottoes, and the employees, were installed in the exposition's Palace of Social Economy and of Congress.[2]

On September 2, 1901, the farm's dairy buildings were destroyed in a fire; the fire was discovered in the dairy building's tower, and the cause of the fire was unknown; insurance paid for any damages. Walter Law promptly arranged the creation of a temporary dairy in a room of the electric plant that had a boiler for sterilizing. The arrangements were made quickly, and by the afternoon, regardless of the farm's large production of milk, processing was handled as usual. A new and larger dairy building was planned to be built, closer to the railroad station for faster shipping.[71]

When the village was incorporated on November 21, 1902, Law owned all but two small parcels of the square mile village, and employed nearly all of its residents, numbering around 100.[1](p19) Law developed the village, establishing schools, churches, parks and the Briarcliff Lodge. The population grew to encourage Law to establish the area as a village. A proposition was presented to the supervisors of Mount Pleasant and Ossining on October 8, 1902 that the area of 640 acres (1 sq mi) with a population of 331 be incorporated as the Village of Briarcliff Manor,[9](p14) and the village was incorporated on November 21.[7](p43)[48] That year Law's son Walter Jr. joined his father and brother Henry in managing the farm and realty company; he went on to become the second village president,[72] in office from 1905 to 1918.[9](p15)[nb 4]

In April 1906, Governor General of Canada Albert Grey, 4th Earl Grey and US Representative and farm architect Edward Burnett toured the farm as guests of Walter Law; the two had driven up from New York City; Briarcliff Outlook described that the two "expressed hearty approval of Briarcliff ways".[73](p358)

Relocation to Pine Plains

Law largely developed his Briarcliff Manor property as a business corporation until 1907, when due to rising property values and diminishing agricultural development in Westchester County, he purchased twelve farms totaling 3,249 acres (5 sq mi) for Briarcliff Farms on both sides of the Pine Plains-Stanford Road (present-day New York Route 82) in Pine Plains, New York;[21] he then began developing his Briarcliff Manor properties for houses, churches, and schools instead. Law's general manager George W. Tuttle arranged the Pine Plains purchases as well as the construction of new barns, a creamery, an electricity-generating power house, and other buildings;[26] Tuttle had worked at Briarcliff Farms since 1901.[21] The barns used Franklin Hiram King's "King System" of ventilation, the dairy building was constructed of concrete, and cost about $25,000 ($656,200 today[23]), and the farm's well was 700 feet away from the barn, 26 feet deep, and 15 feet in diameter.[22]

From 1907 to 1908, the farm and many of its workers moved to the Pine Plains site. Although preliminary steps for the relocation primarily took place gradually, the final transfer occurred in October 1908, when two trains were used to move 300 cattle. The rest of the cattle were transferred a day later, directly to the main station of the Farms, at Barn A.[20](p22) The station was between the Pine Plains and Attlebury stations on the Central New England Railway.[74] During Briarcliff Manor's first automobile race in 1908, the barns were used for mechanic crews so that each driver had his own crew weeks before the race.[9](p12) In 1909, Law formed the Briarcliff Realty Company to sell the original property in Briarcliff Manor, and in 1918, he sold the property in Pine Plains,[1] soon before his death in 1924.[75]

On October 9, 1918,[21][76] New York banker Oakleigh Thorne changed careers[77] and joined several business partners to purchase the 4,200-acre (7 sq mi) Briarcliff Farms property, cattle, and dairy buildings from Walter Law[1](p37) for $500,000 ($7.84 million today[23]).[27] Thorne then began breeding Angus cattle still in the name of Briarcliff Farms, and made the farm equally well known as an Angus beef cattle farm.[21][78] Thorne and W. Alan McGregor had started an Aberdeen-Angus herd, and determined to breed the animals into a large herd. The Aberdeen Angus industry became prominent in the United States due to Briarcliff Farms, which began importing the cattle from Scotland in 1925.[79] In 1955, about 95 percent of US Angus cattle were from the Briarcliff stock.[80]

Thorne hired William Harper Pew after seeing his ability in livestock production lines. At the time, the farm had over 5,000 acres (8 sq mi) and 1,000 purebred Aberdeen Angus cattle, which was the largest Aberdeen Angus herd in the US. Pew went on to start eighteen Angus herds in Dutchess County and serve as a director of the American Angus Association.[81] At the International Livestock Show, the farm exhibited the "International Grand Champion Female" in 1927, the "International Grand Champion Bull" in 1930, and the "International Grand Champion Steers" in 1931 and 1933; in those two years Thorne became the first to win a grand championship at the exposition twice.[77] At the Dutchess County Fair's beef cattle show, 100 cattle and steers were displayed; Briarcliff Farms' steer "Briarcliff Aristocrat" was titled the grand champion steer; the animal was a summer yearling weighing 1,000 pounds. The grand champion bull was Briarcliff Farms' "Briarcliff Barbarian 8th", which was also the first prize senior yearling of the 1933 International Livestock Show. The grand champion female was the farm's "Briarcliff Mighonne 10th", also the first prize senior yearling heifer of the 1933 exposition.[76][82]

The farm had an impact on numerous herds, leading to the Briarcliff prefix being used in many pedigrees in the present day.[76] In 1935, the portion of the farm to the east of the road (2,000 acres (3 sq mi)) was sold. The new owner, Henry Jackson, named the farm "Bethel Farms". After Thorne's death in 1948, the farm changed hands multiple times; in 1968 the farm became a beef feeding operation named Stockbriar Farm.[21] Stockbriar attempted to sell the farm multiple times; it almost was sold as a county zoo.[79] In 1979, Stockbriar sold the farmland to the Conservation and Preservation Association (CAPA) for $2.1 million ($6.82 million today[23]).[83]

In 1982, CAPA hired a Millbrook realtor, who advertised the farm for $2.75 million ($6.72 million today[23]) in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Taconic Press newspapers.[83] Around 1982, Stockbriar Farms filed four lawsuits against CAPA and its lessee Mashomack Fish and Game Preserve over the Pine Plains farm, claiming that the Mashomack Preserve operated a private club there without obtaining necessary liquor permits and that CAPA did not make a payment on March 23, 1982 that constituted the bulk of its total payment for the farm.[84] Stockbriar Farms requested that Mashomack be evicted and the property handed back to Stockbriar Farms.[83] Of the four lawsuits, one was in county court and three were in the New York Supreme Court, and Mashomack and CAPA won the first two.[79] In 1984, a state supreme court justice ordered Mashomack and CAPA to vacate the property; Stockbriar Farms remained open to offers for its purchase.[85]

Current status

Most of the Pine Plains farmland is currently occupied by Thoroughbred breeding farm Berkshire Stud (which purchased 550 acres (0.9 sq mi) there, starting in 1983.[86]) and the Mashomack Polo Club (which owns the farmhouse on Halcyon Lake[21]).[87] The farm's creamery[21] and several barns still exist at Mashomack Polo Club, many built during the 19th century, and repurposed in the 1980s for stables, farm equipment storage, and raising sporting birds. The barns also housed The Triangle Arts Association (part of the Triangle Arts Trust) from 1982 to 1993.[8][88]

In Briarcliff Manor, part of the original Stillman farmhouse currently survives as the rectory of St. Theresa's Catholic Church,[7](p79) and several of the employees' wood-framed cottages still stand on Dalmeny and Old Briarcliff Roads.[3] Similar houses still stand on South State, Pleasantville, and Poplar Roads. The farm's dairy building is currently owned by Consolidated Edison; the company also owns a nearby building that formerly housed the Briarcliff Manor Light and Power Company. The Plasmon Company of America's Woodside Avenue factory is now an automotive restoration facility.[1](pp18, 125)

Gallery

-

A section of the cow stables, with Law's mottoes overhead

-

The "great barn fire", Dalmeny Road, April 28, 1913; next-door to the Briarcliff Fire Company headquarters.[1](p61)

-

The Pocantico Valley, Barn A in the foreground and the school in the background

-

The plasmon factory, now an automotive restoration facility

-

One of the 306-foot-long greenhouses

-

The greenhouses beside the Lodge

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Changing_Landscapewas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

See also

- History of Briarcliff Manor, New York

- History of New York

- Agriculture in the United States

Notes

- ↑ The Briarcliff Lodge's laundry building was built in 1909, was The King's College's music building, and was demolished in summer 2002.[1](pp90, 115)

- ↑ The inquiry was specifically made by George T. Powell and a Pennsylvania farmer named Kelgaard in New York City. The two asked state residents, primarily farmers, about urban migration, tenant farming, and principals of agriculture. The direct result of the research was the founding of the School of Practical Agriculture.[34]

- ↑ Powell was a practical educator and lecturer with Cornell University and the USDA.[10](p338)

- ↑ The title changed to President-Mayor during Henry Law's office (1918-36) and subsequently to Mayor around 1936.[9](p15)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 Yasinsac, Robert (2004). Images of America: Briarcliff Lodge. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3620-0. LCCN 2004104493. OCLC 57480785. OL 3314243M.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 "Christmas Eve at Briarcliff Farms". Social Service (New York, New York: League for Social Service) 3 (1): 8–22. January 1901. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "2014 Summer Newsletter" (PDF). Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society. 2014. pp. 3, 5. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Bosak, Midge, ed. (1977). A Village Between Two Rivers: Briarcliff Manor. White Plains, New York: Monarch Publishing, Inc. OCLC 6163930.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Nurses Visit Briarcliff". The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review (New York, New York) 27 (2). August 1901. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 Bacon, Edgar Mayhew (May 1902). Bailey, L. H., ed. "The Inspiration of a Great Farm". Country Life in America (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Doubleday, Page & Co.) 2 (1): 12–15. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Cheever, Mary (1990). The Changing Landscape: A History of Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough. West Kennebunk, Maine: Phoenix Publishing. ISBN 0-914659-49-9. LCCN 90045613. OCLC 22274920. OL 1884671M.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Mashomack Barn Reservations". Mashomack Polo Club. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 Our Village: Briarcliff Manor, N.Y. 1902 to 1952. Historical Committee of the Semi–Centennial. 1952. OCLC 24569093.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 10.10 10.11 Baker, Caroline Sheridan (December 1900). "Where Women Study Farming". The Puritan, a Journal for Gentlewomen (New York, New York: Frank A. Munsey) 9 (3): 329–344. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 11.10 Hendrick, Burton J. (January 1902). "An American Country Gentleman". Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly 53 (3). Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "A Model Dairy Farm". The Illustrated American (New York, New York) 21 (362): 128. January 16, 1897. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 13.21 13.22 13.23 13.24 13.25 13.26 Blossom, Mary C. (1901). Page, Walter Hines, ed. "The New Farming and a New Life". The World's Work (Doubleday, Page & Company) 3: 1625–1637. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ Wade, Betsy (May 1, 1983). "If You're Thinking of Living in Briarcliff Manor". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ Emerson, Arthur W., ed. (June 1905). Briarcliff Outlook 4 (1). Briarcliff Manor, New York. OCLC 679344578. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ↑ Emerson, Arthur W., ed. (c. 1907). Briarcliff Once-a-Week. Briarcliff Manor, New York. OCLC 679344578. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ↑ Herr, Beth; Koehl, Maureen (2013). Ward Pound Ridge Reservation. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-7385-9905-2. LCCN 2012951208. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Walter W. Law, Jr.". Social Service 3 (4): 99–100. April 1901. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "A Briar Cliff Communal Home". Social Service (New York, New York: League for Social Service) 2 (2): 5. February 1900. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Emerson, Arthur W., ed. (October 4, 1908). Briarcliff Once-a-Week. Briarcliff Manor, New York. OCLC 679344578. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 21.9 21.10 21.11 Duel, Newton; Klare, Elizabeth; Mara, James; Netter, Helen; Wapnick, Dyan (1996). "5: Out of the Wilderness". The Record. The Little Nine Partners Historical Society. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 22.8 22.9 22.10 22.11 "Certified Milk in New York State: Answers to Questions Submitted to Producers of Certified Milk". Eighteenth Annual Report of the Department of Agriculture (Albany, New York: State of New York Department of Agriculture): 35e–38e. 1911. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 23.9 23.10 23.11 23.12 23.13 23.14 23.15 23.16 23.17 23.18 Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2014. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "The Duke Christens a Bull". The New York Times. June 17, 1893. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 "A Great Experiment". The Independent 53 (2762) (New York, New York). November 7, 1901. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Briarcliff Farms Entertain" (PDF). The Pine Plains Register. September 2, 1915. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Thorne Buys Briarcliff Farms". The New York Times. October 10, 1918. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Salmon, D. E. (1903). "The Tuberculin Test for Tuberculosis". Annual Report, Nebraska State Board of Agriculture For the Year 1902 (Lincoln, Nebraska): 244. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ↑ Oliver, John W., ed. (February 8, 1897). "Briar Cliff Farms" (PDF). The Statesman (Yonkers, New York: Yonkers Publishing Company). Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ↑ Emerson, Arthur W., ed. (September 1905). Briarcliff Outlook 4 (4). Briarcliff Manor, New York. OCLC 679344578. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 "The Supply of Milk to Cities". Municipal Journal and Engineer (New York, New York) 20 (6): 132. February 7, 1906. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ Emerson, Arthur W., ed. (June 1904). Briarcliff Outlook 3 (1). Briarcliff Manor, New York. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Oechsner, Carl (1975). Ossining, New York: An Informal Bicentennial History. Croton-on-Hudson, New York: North River Press. ISBN 0-88427-016-5. OCLC 1324414.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 34.5 34.6 34.7 Reynolds, Minnie J. (August 18, 1901). "Training Scientific Farmers". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ A Century of Volunteer Service: Briarcliff Manor Fire Department 1901–2001. Briarcliff Manor Fire Department. 2001. LCCN 00093475. OCLC 48049424.

- ↑ Bailey, L. H., ed. (June 1902). "Briarcliff Products". Country Life in America (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Doubleday, Page & Co.) 2 (2): xxxiv. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 "The Dairy". The Co-operative Journal (Oakland, California: The Co-operative Education Publishing Company) 1 (1): 15. January 1901. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 "The School of Practical Agriculture and Horticulture, Briarcliff Manor, N. Y.". American Gardening; A Weekly Illustrated Journal of Horticulture and Gardeners' Chronicle 21 (280): 317–8. May 5, 1900. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Emerson, Arthur W., ed. (August 1904). Briarcliff Outlook 3 (3). Briarcliff Manor, New York. OCLC 679344578. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ↑ The Medical Directory of New York, New Jersey and Connecticut 2. New York, New York: New York State Medical Association. 1900. p. 697. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Briarcliff Farms". Printers' Ink (New York, New York) 27 (7): 6. May 17, 1899. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ↑ "Briarcliff Lodge". Pearson's Magazine (New York, New York: The Pearson Publishing Co.) 26 (2): 6. August 1911. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 John Steiner, Henry (May 19, 2011). "Briarcliff Manor – The Hudson River Town Six Degrees of Separation". River Journal. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Morton, Julius Sterling, ed. (November 30, 1899). "Millionaires as Farmers". The Conservative (Nebraska City, Nebraska) 2 (21): 4. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Hine, L . W. (December 1905). "The Function of the School Excursion". The Journal of Geography 4 (10): 447. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Sharman, Karen M. (1996). Glory in Glass: A Celebration of The Briarcliff Congregational Church 1896–1996. Briarcliff Manor, New York: Caltone Color Graphics Inc. ISBN 0-912882-96-4. OCLC 429606439.

- ↑ "Westchester Folk Hold Horse Show". The New York Times. July 12, 1931. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Gelard, Donna (2002). Explore Briarcliff Manor: A driving tour. Contributing Editor Elsie Smith; layout and typography by Lorraine Gelard; map, illustrations, and calligraphy by Allison Krasner. Briarcliff Manor Centennial Committee.

- ↑ Marchant, Robert (June 29, 2006). "Historic Briarcliff rose adorns new street signs". The Journal News.

- ↑ The Briarcliff Manor Garden Club Yearbook 2013–2014. Briarcliff Manor Garden Club. September 2013. p. 2.

- ↑ "Living Issues for Pulpit Treatment". The Homiletic Review (New York: Funk and Wagnalls Company) 32 (1): 83. July 1896. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "New Agricultural School.; Briar Cliff Farm Selected by Abram S. Hewitt and His Associates." (PDF). The New York Times. May 1, 1900. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 "School of Agriculture". The New York Times. June 19, 1902. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 "Farming School to be Extended: Experimental Educational Station Proves a Big Success". The San Francisco Call. June 9, 1902. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 "School of Agriculture" (PDF). The Yonkers Statesman. May 8, 1901. p. 5. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 United States Department of Agriculture (1901). Allen, E. W., ed. "A School of Practical Agriculture and Horticulture". Experiment Station Record (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office) 13 (4): 301–2. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Libby, Valencia (June 1984). Henry Francis Du Pont and the Early Development of Winterthur Gardens, 1800-1927. University of Delaware. p. 28. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 United States Department of Agriculture (1902). Allen, E. W., ed. "Notes". Experiment Station Record (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office) 13 (1): 1005. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ United States Department of Agriculture (September 1902). Allen, E. W., ed. "Notes". Experiment Station Record (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office) 14 (1): 515–6. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ↑ "School of Agriculture Closed". The School Journal (New York, New York: E. L. Kellogg & Co.) 66 (14): 398. April 4, 1903. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Loan Funds: Other Pecuniary Aids". Cornell University Register, 1924-25 (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University) 16 (17page=107). September 1, 1925. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ "A history worth reading ...". The Knox School. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ Butter Tests of Registered Jersey Cows 1. New York: American Jersey Cattle Club. January 1889. p. 17. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Stillman's Model Dairy". American Agriculturalist (O Judd Co.) 46 (6): 270. June 1887. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ↑ Pattison, Robert (1939). A History of Briarcliff Manor. William Rayburn. OCLC 39333547.

- ↑ "Our Village: a family place for more than a century". Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Westchester Excels Nevada". The New York Times. December 26, 1904. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Report of the Commissioner-General for the United States to the International Universal Exposition, Paris, 1900 3. Washington, D.C. 1901. pp. 300–1. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ↑ Seventeenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Animal Industry for the Year 1900. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture. 1901. pp. 219–20. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ↑ Tolman, William Howe (1900). Industrial Betterment. New York, New York: The Social Service Press. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Among and About our Commercial Members". Social Service (New York, New York: League for Social Service) 4 (4): 128. October 1901. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ Murlin, Edgar L. (1915). The New York Red Book. Albany, New York: J. B. Lyon Company. p. 164. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ Emerson, Arthur W., ed. (April 1906). Briarcliff Outlook 4 (11). Briarcliff Manor, New York. OCLC 679344578. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Central New England Railway". Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ "Walter W. Law Dies in the South". The New York Times. January 19, 1924. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 Burke, Tom (2013). Shanahan, Mike, ed. "New York – The Mother Church of Angus History". Angus Angles (NY Angus Association). Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Saddle & Sirloin Club Portrait Collection (PDF). Louisville, Kentucky: Kentucky State Fair Board. 2013. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-9634756-4-0. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ Loeb, Penny (July 1982). "Pine Plains' Historical Houses" (PDF). Rhinebeck Gazette. Taconic Newspapers. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 Loeb, Penny (August 19, 1982). "Court Asked to Decide Who Owns Stockbriar" (PDF). The Register Herald 117 (33). p. 3. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Livestock and Livestock Products". Soil Survey of Dutchess County, New York (USDA Soil Conservation Service; Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station): 18. December 1955. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ "William Harper Pew: 1883–1935". Department of Animal Science, Iowa State University. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Honors Go To Briarcliff at County Fair" (PDF). The Register-Herald 53 (36). September 6, 1934. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 Loeb, Penny (August 19, 1982). "Stockbriar Tries to Get Farm Back" (PDF). The Register Herald 117 (33). p. 1. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ Loeb, Penny (March 9, 1983). "Stockbriar Case Will Go to Court March" (PDF). Millbrook Round Table (Millbrook, New York). p. 8. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ Robinson, Tim (April 5, 1984). "Court Evicts Mashomack; Deal Readied" (PDF). The Register Herald 119 (14) (Millbrook, New York). Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Berkshire Stud History". Berkshire Stud. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Berkshire Stud Real Estate". Berkshire Stud. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ↑ "History". Triangle Arts Association. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

External links

![]() Media related to Briarcliff Farms at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Briarcliff Farms at Wikimedia Commons