Longobards in Italy. Places of Power (568-774 A.D.)

| Brescia, Italy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Comune | ||

| Città di Brescia | ||

|

Panorama of Brescia | ||

| ||

|

Nickname(s): Leonessa d'Italia ("Lioness of Italy") La città della Mille Miglia ("The City of the Mille Miglia") | ||

| Motto: Brixia fidelis ("Brescia Faithful") | ||

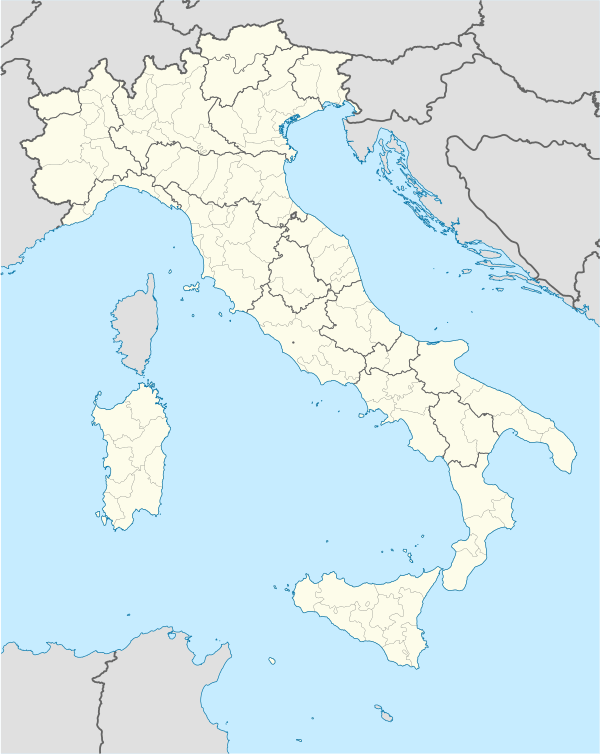

Brescia, Italy Location of Brescia, Italy in Italy | ||

| Coordinates: 45°32′30″N 10°13′00″E / 45.54167°N 10.21667°ECoordinates: 45°32′30″N 10°13′00″E / 45.54167°N 10.21667°E | ||

| Country | Italy | |

| Region | Lombardy | |

| Province | Province of Brescia (BS) | |

| First settlement: Celtic settlement: Roman settlement: |

1200 BC 7th century BC 89 BC | |

| Frazioni | Fornaci, Sant'Eufemia, San Polo, Urago Mella, Sant'Anna, Mompiano | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Emilio Del Bono (PD) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 90.7 km2 (35.0 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 149 m (489 ft) | |

| Population (31 July 2014)[1] | ||

| • Total | 195,568 | |

| • Density | 2,200/km2 (5,600/sq mi) | |

| Demonym | Bresciani | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Postal code | 25100 | |

| Dialing code | 030 | |

| Patron saint | Sts. Faustino and Giovita | |

| Saint day | February 15 | |

| Website | Official website | |

Brescia (Italian: [ˈbreʃʃa]; Lombard: Brèsa [ˈbrɛsɔ] or [ˈbrɛhɔ]; Latin: Brixia) is a city and comune in the region of Lombardy in northern Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, between the Mella River and the Naviglio, a few kilometres from the lakes Garda and Iseo. With a population of around 196,000, it is the second largest city in the region and the fourth of northwest Italy. The urban area of Brescia extends beyond the administrative city limits and has a population of 672,822,[2] while over 1.5 million people live in its metropolitan area.[2] The city is the administrative capital of the Province of Brescia, one of the largest in Italy, with over 1,200,000 inhabitants.

Founded over 3,200 years ago, Brescia (in antiquity Brixia) has been an important regional centre since pre-Roman times. Its old town contains the best-preserved Roman public buildings in northern Italy[3][4] and numerous monuments, among these the medieval castle, the Old and New cathedral, the Renaissance Piazza della Loggia and the rationalist Piazza della Vittoria.

The monumental archaeological area of the Roman forum and the monastic complex of San Salvatore-Santa Giulia have become a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of a group of seven inscribed as Longobards in Italy. Places of the power (568-774 A.D.).[5]

The city is at the centre of the third-largest Italian industrial area, concentrating on mechanical and automotive engineering and machine tools, as well as Beretta and Fabarm firearm manufacturers.

Nicknamed the Leonessa d'Italia ("Lioness of Italy"), Brescia is known for being the original production area of the Franciacorta wine and for the prestigious Mille Miglia car race that starts and ends in this city. In addition, Brescia is the setting for most of the action in Manzoni's Adelchi.

History

Ancient era

Various myths relate to the founding of Brescia: one assigns it to Hercules while another attributes its foundation as Altilia ("the other Ilium") by a fugitive from the siege of Troy. According to another myth, the founder was the king of the Ligures, Cidnus, who had invaded the Padan Plain in the late Bronze Age. Colle Cidneo (Cidnus's Hill) was named after that version, and it is the site of the medieval castle. This myth seems to have a grain of truth, because recent archaeological excavations have unearthed remains of a settlement dating back to 1,200 BC that scholars presume to have been built and inhabited by Ligures peoples.[7][8] Others scholars attribute the founding of Brescia to the Etruscans.

The Gallic Cenomani, allies of the Insubres, invaded in the 7th century BC, and used the town as their capital. The city became Roman in 225 BC, when the Cenomani submitted to the Romans. During the Carthaginian Wars, 'Brixia' (as it was called then) was usually allied with the Romans. In 202 BC, it was part of a Celtic confederation against them but, after a secret agreement, changed sides and attacked and destroyed the Insubres by surprise. Subsequently the city and the tribe entered the Roman world peacefully as faithful allies, maintaining a certain administrative freedom. In 89 BC, Brixia was recognized as civitas ("city") and in 41 BC, its inhabitants received Roman citizenship. Augustus founded a civil (not military) colony there in 27 BC, and he and Tiberius constructed an aqueduct to supply it. Roman Brixia had at least three temples, an aqueduct, a theatre, a forum with another temple built under Vespasianus, and some baths.

When Constantine advanced against Maxentius in 312, an engagement took place at Brixia in which the enemy was forced to retreat as far as Verona. In 402, the city was ravaged by the Visigoths of Alaric I. During the 452 invasion of the Huns under Attila, the city was besieged and sacked. Forty years later, it was one of the first conquests by the Gothic general Theoderic the Great in his war against Odoacer.

Middle Ages

.jpg)

In 568 (or 569), Brescia was taken from the Byzantines by the Lombards, who made it the capital of one of their semi-independent duchies. The first duke was Alachis, who died in 573. Later dukes included the future kings Rotharis and Rodoald, and Alachis II, a fervent anti-Catholic who was killed in the battle of Cornate d'Adda (688). The last king of the Lombards, Desiderius, had also been duke of Brescia.

In 774, Charlemagne captured the city and ended the existence of the Lombard kingdom in northern Italy. Notingus was the first (prince-)bishop (in 844) who bore the title of count (see Bishopric of Brescia). From 855 to 875, under Louis II the Younger, Brescia become de facto capital of the Holy Roman Empire. Later the power of the bishop as imperial representative was gradually opposed by the local citizens and nobles, Brescia becoming a free commune around the early 12th century. Subsequently it expanded into the nearby countryside, first at the expense of the local landholders, and later against the neighbouring communes, notably Bergamo and Cremona. Brescia defeated the latter two times at Pontoglio, then at the Grumore (mid-12th century) and in the battle of the Malamorte (Bad Death) (1192).

During the struggles in 12th and 13th centuries between the Lombard cities and the German emperors, Brescia was implicated in some of the leagues and in all of the uprisings against them. In the Battle of Legnano the contingent from Brescia was the second in size after that of Milan. The Peace of Constance (1183) that ended the war with Frederick Barbarossa confirmed officially the free status of the comune. In 1201 the podestà Rambertino Buvalelli made peace and established a league with Cremona, Bergamo, and Mantua. Memorable also is the siege laid to Brescia by the Emperor Frederick II in 1238 on account of the part taken by this city in the battle of Cortenova (27 November 1237). Brescia came through this assault victorious. After the fall of the Hohenstaufen, republican institutions declined at Brescia as in the other free cities and the leadership was contested between powerful families, chief among them the Maggi and the Brusati, the latter of the (pro-imperial, anti-papal) Ghibelline party. In 1258 it fell into the hands of Ezzelino da Romano.

In 1311 Emperor Henry VII laid siege to Brescia for six months, losing three-fourths of his army. Later the Scaliger of Verona, aided by the exiled Ghibellines, sought to place Brescia under subjection. The citizens of Brescia then had recourse to John of Luxemburg, but Mastino II della Scala expelled the governor appointed by him. His mastery was soon contested by the Visconti of Milan, but not even their rule was undisputed, as Pandolfo III Malatesta in 1406 took possession of the city. However, in 1416 he bartered it to Filippo Maria Visconti duke of Milan, who in 1426 sold it to the Venetians. The Milanese nobles forced Filippo to resume hostilities against the Venetians, and thus to attempt the recovery of Brescia, but he was defeated in the battle of Maclodio (1427), near Brescia, by general Carmagnola, commander of the Venetian mercenary army. In 1439 Brescia was once more besieged by Francesco Sforza, captain of the Venetians, who defeated Niccolò Piccinino, Filippo's condottiero. Thenceforward Brescia and the province were a Venetian possession, with the exception of the years between 1512 and 1520, when it was occupied by the French armies under Gaston of Foix, Duke of Nemours.

Modern era

%2C_Mappa_di_Brescia_a_inizio_Settecento.jpg)

Brescia has had a major role in the history of the violin. Many archive documents testify that from 1585 to 1895 Brescia was the cradle of a magnificent school of string players and makers, all styled "maestro", of all the different kinds of stringed instruments of the Renaissance: viola da gamba (viols), violone, lyra, lyrone, violetta and viola da brazzo. So you can find "maestro delle viole" or "maestro delle lire" and later, at least from 1558, "maestro di far violini" that is master of violin making. From 1530 the word violin appeared in Brescian documents and spread throughout north of Italy.

Early in the 16th century Brescia was one of the wealthiest cities of Lombardy, but it never recovered from its sack by the French in 1512.

It subsequently shared the fortunes of the Venetian republic until the latter fell at the hands of French general Napoleon Bonaparte; in Napoleonic times, it was part of the various revolutionary republics and then of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy after Napoleon became Emperor of the French.

In 1769, the city was devastated when the Bastion of San Nazaro was struck by lightning. The resulting fire ignited 90,000 kg (198,416 lb) of gunpowder stored there, causing a massive explosion which destroyed one-sixth of the city and killed 3,000 people.

After the end of the Napoleonic era in 1815, Brescia was annexed to the Austrian puppet state known as the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia. Brescia revolted in 1848; then again in March 1849, when the Piedmontese army invaded Austrian-controlled Lombardy, the people in Brescia overthrew the hated local Austrian administration, and the Austrian military contingent, led by general Haynau, retreated to the Castle. When the larger military operations turned against the Piedmontese, that retreated, Brescia was left to its own resources, but managed to resist recapture by the Austrian army for ten days of bloody and obstinate street fighting that are now celebrated as the Ten Days of Brescia. This prompted poet Giosuè Carducci to nickname Brescia "Leonessa d'Italia" ("Italian Lioness"), since it was the only Lombard town to rally to King Charles Albert of Piedmont in that year.

In 1859, the citizens of Brescia voted overwhelmingly in favor of its inclusion in the newly founded Kingdom of Italy.

The city was awarded a Gold Medal for its resistance against Fascism in World War II.

On May 28, 1974, it was the seat of the bloody Piazza della Loggia bombing.

Geography

Topography

Brescia is located in the north-eastern section of the Po Valley, at the foot of the Brescian Prealps, between the Mella and the Naviglio, with the Lake Iseo to the west and the Lake Garda to the east. The municipal territory is mostly flat, although the Monte Maddalena in the north-east is the highest point of the city at 874 m above sea level. The administrative commune covers an area of about 90 square kilometres, with a population, in 2014, of 194,559[10] and a population density of 2,145 inhabitants per square kilometres.

Modern Brescia has a central area focused on residential and tertiary activities. Around the city proper, lies a vast urban agglomeration with over 600,000 inhabitants that expands mainly to the north, to the west and to the east, engulfing many communes in a continuous urban landscape.

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification, Brescia has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa). Its average annual temperature is 13.7 °C (57 °F): 18.2 °C (65 °F) during the day and 9.1 °C (48 °F) at night. The warmest months are June, July, and August, with high temperatures from 27.8 °C (82 °F) to 30.3 °C (87 °F). The coldest are December, January, and February, with low temperatures from −1.5 °C (29 °F) to 0.6 °C (33 °F).

Winter is not very cold and snowfall is rare (average 21 cm (8 in) per year), mainly occurs from December through February, but snow cover does not usually remain for long. Summer can be sultry, when humidity levels are high and peak temperatures can reach 35 °C (95 °F). Spring and autumn are generally pleasant, with temperatures ranging between 10 °C (50 °F) and 20 °C (68 °F).

The relative humidity is high throughout the year, especially in winter when it causes fog, mainly from dusk until late morning, although the phenomenon has become increasingly less frequent in recent years.

Precipitation is spread evenly throughout the year. The driest month is December, with precipitation of 54.6 mm (2.1 in), while the wettest month is May, with 104.9 mm (4.1 in) of rain.

| Climate data for Brescia Ghedi (1971–2000, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

22.0 (71.6) |

27.3 (81.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

36.2 (97.2) |

37.2 (99) |

38.4 (101.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

29.0 (84.2) |

22.8 (73) |

17.0 (62.6) |

38.4 (101.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

8.5 (47.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.2 (63) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.5 (83.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

18.0 (64.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.9 (66) |

13.3 (55.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.8 (37) |

6.6 (43.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

2.8 (37) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

7.7 (45.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −19.4 (−2.9) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

0.2 (32.4) |

5.2 (41.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−19.4 (−2.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 65.5 (2.579) |

47.9 (1.886) |

56.0 (2.205) |

67.3 (2.65) |

82.6 (3.252) |

83.4 (3.283) |

74.0 (2.913) |

74.2 (2.921) |

89.2 (3.512) |

111.9 (4.406) |

73.8 (2.906) |

62.4 (2.457) |

888.2 (34.969) |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.7 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 8.1 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 82.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 81 | 75 | 76 | 73 | 71 | 72 | 72 | 75 | 79 | 85 | 86 | 78 |

| Source: Servizio Meteorologico (humidity 1961–1990)[11][12][13] | |||||||||||||

Government

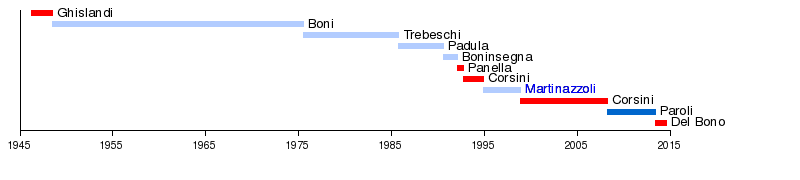

Since local government political reorganization in 1993, Brescia has been governed by the City Council of Brescia, which is based in Palazzo della Loggia. Voters elect directly 33 councilors and the Mayor of Brescia every five years.

Between the 1994 and 2008 local elections, the center-left coalition held the largest number of seats with a partnership administration based on the alliance between Italian People's Party, Democrats of the Left and other minor left-wing and green parties. In the 2008 local election the center-right coalition formed by Silvio Berlusconi's People of Freedom party and the regionalist Lega Nord won the majority in the City Council. In the 2013 elections the Democratic Party achieved an outright majority, after gaining an additional 5 seats across the city. The current Mayor of Brescia is Emilio Del Bono (PD), elected on 10 June 2013.

Brescia is also the capital of its own province. The Provincial Council is seated in Palazzo Broletto.

Timeline of the mayors of Brescia

(red: centre-left party; blue: centrist party; dark blue: centre-right party)

Boroughs

The city of Brescia is divided in 5 boroughs called circoscrizioni:

| rowspan"1" style="border-bottom:1px solid gray; vertical-align:top;" class="sortable"|Circoscrizione | rowspan"1" style="border-bottom:1px solid gray; vertical-align:top;" class="sortable"|Population 31 December 2010 |

rowspan"3" style="border-bottom:1px solid gray; vertical-align:top;" class="unsortable"|Map |

|---|---|---|

| Historical Center | 41,856 |  |

| North | 41,772 | |

| West | 37,773 | |

| South | 44,281 | |

| East | 28,070 |

Main sights

The old town of Brescia (characterized, in the north-east, by a rectangular plan, with the streets that intersect at right angles, a peculiarity handed down from Roman times) has a significant artistic and archaeological heritage, consisting of various monuments ranging from the ancient age to contemporary.

| The monumental area with the monastic complex of San Salvatore-Santa Giulia (Longobards in Italy. Places of Power; 568-774 A.D.) | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

The Capitolium in the Roman forum. The Capitolium in the Roman forum. | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, vi |

| Reference | 1318 |

| UNESCO region | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2011 (35th Session) |

_int2.jpg)

1.jpg)

UNESCO World Heritage monuments

In 2011, UNESCO has inscribed in the World Heritage List, belonging the group known as "Longobards in Italy, Places of Power (568-774 A.D.)", the following monuments of Brescia:

- Monumental area of the Roman forum

This is the archaeological complex where there are the best-preserved Roman public buildings in the northern Italy,[3][4] composed of:

- Republican sanctuary

- It is under the Capitoline temple. It has been built in the 1st century BC and it is the oldest structure of the forum. It consists of four rectangular rooms next to each other and inside then there are the remains of the original mosaic floors and the wall frescoes, which from a stylistic point of view and state of preservation are comparable to those of Pompeii.[14] It is not open to the public, because it is still undergoing archaeological excavation and restoration.

- Capitolium

- It was the most important temple of the ancient Brixia, dedicated to the cult of the Capitoline Triad. It was built in 73 AD and consists of three cellae that have preserved much of the original polychrome marble floors,[14] while their interior walls are decorated by ancient Roman epigraphs placed here in the 19th century. In front of them, there are the remains of the portico, composed of Corinthian columns that support a pediment containing a dedication to the Emperor Vespasian. Almost entirely buried by a landslide of the Cidneo Hill, it was rediscovered in 1823 through various archaeological campaigns. During excavation in 1826, a splendid bronze statue of a winged Victory was found inside it, likely hidden in late antiquity to preserve it from one of the various lootings that the town had to endure in those times. Since the spring of 2013, after a new archaeological restoration, it has opened again to the public.

- Roman theatre

- It is located immediately at east of the Capitolium. It has been built in the Flavian era and altered in the 3rd century. With its 86 meters diameter, is one of the largest Roman theatres in northern Italy and originally it housed around 15,000 spectators. In the 5th century, an earthquake has heavily damaged the building. In addition, in later centuries, its remains were incorporated into new buildings built on top of it, largely demolished starting from the 19th century. Of the original structure are preserved the semicircular perimeter walls, the two side passages (aditus) and the remains of the proscenium, as well as many fragments of columns and friezes of the scaenae frons. The most of the orchestra and the ima cavea are still below ground. The archaeological excavations should resume in the coming years.

Near the Capitolium is located the Palazzo Maggi Gambara, an aristocratic palace built in the 16th century on top of the west ruins of the Roman theatre.

It is an outstanding architectural palimpsest,[3][15] today transformed into the Museo di Santa Giulia, which contains about 11,000 works of art and archaeological finds.[16] During the period of Longobard domination, Princess Anselperga, daughter of King Desiderius, headed the monastery. It consists of:

- Basilica of San Salvatore

- It has been built in 753 by Duke of Brescia Desiderius, future Lombard king, and his wife Ansa. It is characterized by the simultaneous use of the Longobards stylistic elements and decorative motifs of classical and Byzantine art and it is one of the most important examples of High Middle Ages architecture in Italy.[17] The basilica has a nave with two apses and has a transept with three apses. It is located over a pre-existing church, which had a single nave and three apses. Expanded in the following centuries, it houses various works of art, including the Stories of St. Obizio painted by Romanino and Stories of the Virgin and the infancy of Christ by Paolo Caylina il Giovane,[18] as well as others from the Carolingian age.

- Church of Santa Maria in Solario

- It has been built in the mid-12th century as a chapel inside the monastery. It has a square base with an octagonal lantern and has two internal levels.[18] Four vaults, supported in the centre by an ancient Roman altar, covers the lower floor, while a hemispherical dome covers the upper chamber, that has, into the east wall, three small apses. Inside there are frescoes by Floriano Ferramola and two of the most important pieces of the treasure of the ancient monastery: the Brescia Casket (that consists of a small ivory box dating the 4th century) and the Cross of Desiderius (made of silver and gold plate, studded with 212 precious gems).[19]

- The nuns' choir

- It is placed between the Basilica of San Salvatore and the church of Santa Giulia. It has been built between the late 15th and early 16th century and it is on two levels. The lower level is the old churchyard covered for access to the basilica. The upper floor is the real choir, made up by a room covered by a barrel vault, which is connected to the east with San Salvatore by three small windows with a grating, on the west by Santa Giulia through an arch. The interior of the choir is entirely decorated with frescoes painted by Ferramola and Caylina, and inside are shown different funerary monuments of the Venetian age, including the Martinengo Mausoleum, a masterpiece of the Renaissance sculpture in Lombardy.[20]

- Church of Santa Giulia

- It has been built between 1593 and 1599. The façade, made of Botticino marble, is decorated with a double row of pilasters of the Corinthian order, separated by a rich marble frieze and connected to the sides by volutes. The inside consists of a spacious nave covered with a barrel vault. In the church, there are no sacred furniture and there are only a few scraps of the frescoes that originally decorated each surface. Although annexed to the monastery, it is not part of the Museo di Santa Giulia and is used as a conference room.[18]

In the former vegetable garden of this monastery have been discovered a group of Roman domus called Domus dell’Ortaglia that were used between the 1st and 4th centuries and they are some of the best preserved domus in northern Italy.

Others sights

.jpg)

- Piazza della Loggia, Brescia, a noteworthy example of Renaissance piazza, with the eponymous Palazzo della Loggia (the current Town Hall) built in 1492 under the direction of Filippo de' Grassi and later completed in the 16th century under the supervision of Sansovino and Palladio. In 1769, Vanvitelli designed the upper room of the palace. On the south side of the square are aligned the two Monti di Pietà ("Mounts of Piety") built between the 15th and the 16th century. The façades of these two buildings, entirely covered by ancient Roman tombstones, constitute the oldest lapidary museum of Italy.[21] At the centre of the east side of the square stands a tower with a large astronomical clock dating back to the mid 16th century, on top of which there are two copper automata depicting two men which strike the hours on a bell. On May 28, 1974, the square was the location of a terrorist bombing.

- Duomo Vecchio ("Old Cathedral"), also known as La Rotonda. It is an exteriorly rusticated Romanesque church, striking for its circular shape. The main structure was built in the 11th century on the ruins of an earlier basilica. Near the entrance is the pink Veronese marble sarcophagus of Berardo Maggi, while in the presbytery is the entrance to the crypt of San Filastrio. The structure houses paintings of the Assumption, the Evangelists Luke and Mark, the Feast of the Paschal Lamb, and Eli and the Angel by Alessandro Bonvicino (known as il Moretto); two canvasses by Girolamo Romanino, and paintings by Palma il Giovane, Francesco Maffei, Bonvicino, and others.[22]

- Duomo Nuovo ("New Cathedral"). Construction on the new cathedral began in 1604 and continued until 1825. While initially a contract was awarded to Palladio, economic shortfalls awarded the project, still completed in a Palladian style, to the young Brescian architect Giovanni Battista Lantana, with decorative projects directed mainly by Pietro Maria Bagnadore. The façade is designed mainly by Giovanni Battista and Antonio Marchetti, while the cupola was designed by Luigi Cagnola. Interior frescoes including the Marriage, Visitation, and Birth of the Virgin, as well as the Sacrifice of Isaac, were frescoed by Bonvicino. The main attraction is the Arch of Sts. Apollonius and Filastrius (1510).[23]

- The Broletto, Brescia, the medieval Town Hall, which now hosts offices of both the Municipality and the Province. It is a massive 12th- and 13th-century building; on the front, the balcony where the medieval city officials spoke to the townsfolk from; on the north side, still standing one (Lombard: Tòr del Pégol) of the two original city towers, with a belfry still hosting the bells used of old to call all hands in moments of distress.

- Piazza della Vittoria, an example of Italian rationalism architecture. It has been built between 1927 and 1932 by architect Marcello Piacentini through the demolition of part of the medieval old town and it has an L-shape. On the inside corner right there is the Torrione, the first skyscraper built in Italy.[9] In the north background there is the large Palazzo delle poste ("Post Office building"), with its ocher-white two-tone upholstery. The Torre della Rivoluzione ("Tower of the Revolution") and three other buildings, recalling the classical architecture, complete the square.

- Piazza del Foro. It marks the site of the Roman forum. In addition to the already mentioned Capitolium, republican sanctuary and Roman theatre, various other remains are visible in the area. Among these, on the south side of the square, are scanty remains of a building called the curia, which may have been a basilica.

- Palazzo Martinengo Cesaresco Novarino. It is an aristocratic palace built in the middle of the 17th century, on the remains of an earlier 14th century construction. It is home to art exhibitions and an underground archaeological tour, which constitutes an extraordinary stratification, a complete picture of the city's history from the early Iron Age to the present day, concentrating in a single place 3,000 years of urban history of Brescia.[24]

- Church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli, built between 1488 and 1523. The fine façade by Giovanni Antonio Amadeo, decorated with bas-reliefs and a Renaissance peristilium, is considered a jewel of Lombard Renaissance sculpture.[25]

- The Romanesque-Gothic church of St. Francis of Assisi, with a Gothic façade and cloisters.

- The Castle of Brescia, also known as Falcone d’Italia ("falcon of Italy"), is situated at the northeast angle of the town, on top of Cidneo Hill. It has been built between the 13th and the 16th century and it is one of the largest castles in Italy.[26] Besides commanding a fine view of the city and a large part of the surrounding area, and being a local favorite recreational area, it hosts the Arms Museum, with a fine collection of weapons from the Middle Ages onwards; the Risorgimento Museum, dedicated to the Italian independence wars of the 19th century; an exhibition of model railroads; and an astronomical observatory.

- Church of Santi Nazaro e Celso, with the Averoldi Polyptych by Titian.

- Church of San Faustino e Giovita, also known as San Faustino Maggiore. The interior of the church has extensive frescoes, including the Apotheosis of Saints Faustino, Jovita, Benedict and Scholastica by Giandomenico Tiepolo.

- Basilica of Santa Maria delle Grazie. It has been built between the 16th and the 17th century and it houses various works of local authors, including a painting by Moretto. The interior of the church is entirely covered by frescoes and stucco, making it the most important example of baroque art in the city.

- Church of St. Joseph. It has been built during the 16th century and it is home to a vast quantity of paintings, wall paintings, stucco and other decorative inserts. On the walls of the aisles are hung fourteen Stations of the Cross of St. Joseph, executed in 1713 by Giovanni Antonio Cappello. The church houses the tombs of important personalities in the field of music, such as Gasparo da Salò, who is one of the first that has created and devised the violin and Benedetto Marcello, a great exponent of Italian Baroque music. Inside it, there is one of the oldest organs in the world.[27]

- Church of San Clemente, with numerous painting by Alessandro Bonvicino (generally known as Moretto).

- Torre della Pallata, Brescia ("Pallata Tower"). It has been built in 1254 as part of the medieval walls. The name "Pallata" comes from a fence erected as a defence. In the 15th century were added the clock, the blackbirds and the turret. On the western side of the tower there is a fountain, designed in 1597 by Pier Maria Bagnadore.

- Church of San Giovanni, with a refectory painted partly by the Moretto and partly by Girolamo Romanino.

- Monumental Cemetery, also known as Vantiniano. It is the largest cemetery in Brescia, built around 1813 by Rodolfo Vantini. It is the first monumental cemetery built in Italy[28] and at its centre stands the Lighthouse of Brescia (60 meters tall) which has inspired the architect Heinrich Strack for the design of the Berlin Victory Column.[29]

- Museo di Santa Giulia. This is the City Museum, situated in the monastic complex of San Salvatore-Santa Giulia, which has a rich Roman section. One of the masterpieces is the bronze statue of a winged Victory, originally probably a Venus, converted in antiquity into the Victory by adding the wings; it is said to be in the act of writing the winner's name on her shield (now lost). Also very interesting, one of the very few places in the world where the remains of two Roman domus can be visited on their original site simply by strolling into one of the Museum halls.

- Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo (currently closed for renovations), the municipal art gallery; it hosts works of the painters of the classical Brescian school, Romanino, Bonvicino, and Bonvicino's pupil, Giovanni Battista Moroni.

- Teatro Grande. It is an opera house renovated several times between the mid-17th and mid-19th century. The name Grande ("Big") is derived from the former name Il Grande ("The Great") in honour of Napoleon Bonaparte. The horseshoe-shaped auditorium is richly decorated and has five galleries. From 1912, the theatre is a national monument.[30]

- Biblioteca Queriniana, containing rare early manuscripts, including a 14th-century manuscript of Dante, and some rare incunabula.

The city has no fewer than seventy-two public fountains. The stone quarries of Botticino, 8 km (5 mi) east of Brescia, supplied marble for the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II in Rome.

Economy

The city is at the centre of the third largest Italian industrial area.[31] The local Confindustria, the AIB - Associazione Industriale Bresciana (Industrial Association of Brescia), was the first industry association founded in Italy in 1897.[32] The Brescian companies are typically a small or medium-sized, often family-run, ranging from the food to the engineering industry.

Agriculture

The viticulture is the most important agricultural sector of the Brescian food system. The municipality of Brescia is part of the production areas of five different wines: a DOCG wine, i.e. the Franciacorta,[33] three DOC wines (Botticino,[34] Cellatica[35] and Curtefranca[36]) and an IGT wine (Ronchi di Brescia[37]). In addition, in its old town, along the northern slope of the Cidneo Hill, there is the largest urban vineyard in Europe,[38] characterized by the cultivation of Invernenga, a local white grape variety present in Brescia since Roman times.[39]

Another very important sector is the production of olive oil, especially in the nearby area of Lake Garda. The European Union has recorded as PDO two typologies of extra virgin olive oils and they are Garda and Laghi lombardi.

Industry and services

The main industrial activities of Brescia are those mechanical, specialized in the production and distribution of machine tools. Also important is the production of motor vehicle, represented by the OM, which is the manufacturer of Iveco trucks, and the production of weapons, among which the Beretta, Fabarm and Perazzi. Very important is the metallurgical industry. On the outskirts of town, there are two steel mills: the "Alfa Acciai" and "Ori Martin". Other crucial industrial activities are the production of cutlery and faucets, along with the textile, footwear and clothing, as well as the production of building materials and bricks. The intense industrial development has resulted in a high level of pollution in the outskirts of the city located near the disused chemical factory "Caffaro" that produced PCB. For this reason, this part of the city is in the list of SIN - Siti di Interesse Nazionale (Sites of National Interest).

Brescia hosts the headquarters of several industry groups, including the Lucchini Group, the Feralpi and the Camozzi Group. Brescia is also home to the A2A Group (the result of the merger of ASM Brescia, AEM Milano and AMSA).

The financial sector is also a major employer, with the presence of several branches of banks and financial assets. The UBI Banca Group, fourth largest banking group in Italy, has several division headquarters in the city.

Tourism

The significant historical and artistic heritage of Brescia (from 2011 in the UNESCO World Heritage list) and the natural beauties of its surrounding area (like the Lake Garda, the Val Camonica and the Lake Iseo) have allowed the city to attract an increasing number of visitors. In 10 years, the number of tourists who visited Brescia has almost doubled from 142,556 in 2003[40] to over 280,000 in 2013.[41]

Transportation

Brescia Metro

The Brescia Metro is a rapid transit network that opened on 2 March 2013.[42] The network comprises one line, 13.7 kilometres (9 mi) long,[43] with 17 stations[43] between Buffalora and Prealpino, of which 13 are underground.

The first projects for a metro in Brescia date back to 1980s, with the introduction of the first fully automatic light metro systems in other mid-size cities in Europe. Two feasibility studies were commissioned in 1987. The automatic light metro system was chosen as the best technology for the city. The first public tender was announced in 1989. But this project was then cancelled in 1996.

In 1994, the first application for public financing was issued. The public financing form the central government arrived in 1995, while other funds arrived in 2002 from the Region. The international public bid for the first phase of the project was announced in 2000. The winning proposal was from a group of companies comprising Ansaldo STS, AnsaldoBreda, Astaldi and Acciona, with a system similar to that of the Copenhagen metro.

A €575 million contract was awarded to a consortium led by Ansaldo STS in April 2003.[44] Work started in January 2004, but archaeological finds caused delays and required station redesigns. The line opened on 2 March 2013.[42][45]

Airports

- about 15 km (9 mi) south-east of Brescia you can find the Brescia Airport

- about 50 km (31 mi) north-west of Brescia you can find the Bergamo Orio al Serio Airport

- about 60 km (37 mi) east of Brescia you can find the Verona Villafranca Airport

- about 85 km (53 mi) west of Brescia you can find the Linate Airport

- about 135 km (84 mi) west of Brescia you can find the Malpensa Airport

Sports

Brescia was the starting and end point of the historical car race Mille Miglia that took place annually in May until 1957 on a Brescia-Rome-Brescia itinerary, and also the now defunct Coppa Florio, one of the first ever sport motor races. The Mille Miglia tradition is now kept alive by the "Historic Mille Miglia",[46] a world-class event that gathers in Brescia every year thousands of fans of motor sports and of vintage sports cars. The only cars admitted to the race are the ones that could have competed in (although they do not necessarily have to have taken part in) the original Mille Miglia. The race nowadays is not however a speed race anymore, but rather a "regularity" race; speed races have actually been banned on regular roads in Italy because of the deadly accident that killed a driver and ten bystanders in the last minutes of the 1957 Mille Miglia - that therefore became the last of the original races.

Brescia is also the home of the Brescia Calcio football club and the Rugby Leonessa 1928.

Fencing

- since 1984 the fencingclub Schermabrescia is active.

- the in Brescia born foil-fencer Andrea Cassarà wins at the 2011 World Fencing Championships gold.

Notable people

- Marcus Nonius Macrinus, Roman general and consul to Emperor Marcus Aurelius

- Rothari or Rotari, King of the Lombards

- Rodoald or Rodoaldo, King of the Lombards

- Desiderius, King of the Lombards

- Louis II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frankish emperor and King of Italy

- Arnold of Brescia, a dissident monk who lived in the 12th century

- Albertanus of Brescia, 13th-century Latin author

- Vincenzo Capirola, composer

- Vincenzo Foppa, painter

- Girolamo Savoldo, painter

- Girolamo Romani, also known as "Romanino", painter

- Alessandro Bonvicino, also known as "Moretto", painter

- Luca Marenzio, composer

- Biagio Marini, composer

- Giovanni Battista Fontana, composer

- Laura Cereta, 1469–99, humanist author.

- Veronica Gambara (1485–1550), poet and stateswoman.

- Giovanni Paoli (Juan Pablos), who brought the printing press to the new world in Mexico City under the viceroyalty of Antonio de Mendoza from Spain in 1535

- Saint Angela Merici, who founded the Order of Ursulines in Brescia in 1535

- Gasparo da Salò, born 1540, died 1609 - pioneer of violin making

- Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia (1499-1557), mathematician

- Giulio Alenio, (Brescia 1582-Yanping 1649) Jesuit missionary called the "Confucius from the West"

- Francesco Lana de Terzi (1631–1687), aeronautics and braille pioneer

- Benedetto Castelli, mathematician and expert in hydraulics in the early 17th century

- Paris Francesco Alghisi (1666–1733), composer

- Pietro Gnocchi 1689–1775, eccentric polymath and composer

- Bartolomeo Beretta, gunsmith and founder of the Beretta firearm company

- Giuseppe Zanardelli (1826 - 1903), jurist, politician, prime minister of the Kingdom of Italy (1901–1903)

- Saint Maria Crocifissa di Rosa, who founded the Handmaids of Charity order of nuns in Brescia in 1840

- Camillo Golgi, experimental pathologist, born 1843, died 1926, who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906 for his studies of the structure of the nervous system

- Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, a pianist of the 20th century

- Pope Paul VI, born nearby in Concesio as Giovanni Battista Montini (1897–1978).

- Saint Giovanni Battista Piamarta, who was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI with some others on 2012 October 21.

- Guglielmo Achille Cavellini (1914–1990), art collector and artist

- Andrea Pirlo, football player

- Mario Balotelli, football player

- Manuel Belleri, football player

- Giacomo Agostini born 1942, Grand Prix motorcycle racer and World Champion 1964–1977

- Marco Cassetti, football player

- Sergio Scariolo, basketball coach

- L'Aura, born 1984, singer-songwriter

- Giuliano Paratico, musician, ca. 1550

International relations

In Brazil there is a town called Nova Bréscia. This name was given by its first citizens, who were from Brescia.

Twin towns—Sister cities

Brescia is twinned with:

Bethlehem, Palestinian Authority[47]

Bethlehem, Palestinian Authority[47] Bouaké, Ivory Coast[48][49][50]

Bouaké, Ivory Coast[48][49][50] Darmstadt, Germany (1991)[51]

Darmstadt, Germany (1991)[51] Kaunas, Lithuania

Kaunas, Lithuania Logroño, Spain

Logroño, Spain Maringá, Brazil[52]

Maringá, Brazil[52] Toluca, Mexico

Toluca, Mexico Shenzhen, China[53][54][55]

Shenzhen, China[53][54][55]

See also

- Bishopric of Brescia

- University of Brescia

- Congregation of the Holy Family of Nazareth

References and sources

- References

- ↑ ISTAT

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Urbanismi in Italia, 2011" (PDF). cityrailways.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Italia langobardorum, la rete dei siti Longobardi italiani iscritta nella Lista del Patrimonio Mondiale dell'UNESCO" [Italia langobardorum, the network of the Italian Longobards sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List]. beniculturali.it (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "THE LONGOBARDS IN ITALY. PLACES OF THE POWER (568-774 A.D.). NOMINATION FOR INSCRIPTION ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST" (PDF). unesco.org. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ ""Brescia: description of goods" on Italialangobardorum.it". Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ↑ Clara Stella (2003). Brixia. Scoperte e riscoperte (in Italian). Milano: Skira.

- ↑ "History of Brescia: the origins and the Roman Brescia". turismobrescia.it. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ "Storia del Colle Cidneo" [History of the Cidneo Hill]. bresciamusei.com (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 F. Robecchi; G. P. Treccani (1993). Piazza della Vittoria (in Italian). Brescia: Grafo.

- ↑ "Demographic Balance for the year 2014 (provisional data)". demo.istat.it. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ "Brescia/Ghedi (BS)" (PDF). Atlante climatico. Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ↑ "STAZIONE 088-BRESCIA GHEDI: medie mensili periodo 61 - 90". Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Brescia Ghedi: Record mensili dal 1951" (in Italian). Servizio Meteorologico dell’Aeronautica Militare. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Brescia: monumental area". italialangobardorum.it. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Brescia: San salvatore-Santa Giulia complex". italialangobardorum.it. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Santa Giulia Museum Complex". bresciamusei.com. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Pierluigi De Vecchi; Elda Cerchiari (1991). L'arte nel tempo (in Italian). Milano: Bompiani.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Renata Stradiotti (2001). San Salvatore - Santa Giulia a Brescia. Il monastero nella storia (in Italian). Milano: Skira.

- ↑ "Brescia: Longobard Monastery". italialangobardorum.it. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Santa Giulia Museum Complex: the choir.". bresciamusei.com. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "The Old and New Monte di Pietà". turismobrescia.it. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Duomo Vecchio

- ↑ Duomo Nuovo.

- ↑ "Palazzo Martinengo". provinciadibresciaeventi.com (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli". turismobrescia.it. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "The Castle". turismobrescia.it. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Francesco de Leonardis (2008). Guida di Brescia (in Italian). Brescia: Grafo Edizioni.

- ↑ "Cimitero Vantiniano" [Vantiniano Cemetery]. touringclub.com (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Valerio Terraroli (1990). Il Vantiniano: la scultura monumentale a Brescia tra Ottocento e Novecento (in Italian). Brescia: Grafo.

- ↑ "Teatro Grande, 100 anni da Monumento Nazionale". teatrogrande.it (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Massimiliano Del Barba (February 26, 2014). "Brescia ritorna il terzo polo industriale. Ma l’occupazione rischia un nuovo calo." [Brescia becomes again the third largest industrial centre. But for the employment rate is likely a new drop.] (in Italian). Corriere della Sera.

- ↑ "AIB-Associazione Industriale Bresciana. La storia." [AIB-Industrial Association of Brescia. The history.]. aib.bs.it (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Franciacorta DOCG, disciplinare di produzione" [Franciacorta DOCG, production regulations]. agraria.org (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Botticino DOC". agraria.org (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Cellatica DOC". agraria.org (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Curtefranca DOC". agraria.org (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Ronchi di Brescia IGT". agraria.org (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Michela Bono (September 11, 2012). "Il vigneto Pusterla rinasce e torna alla famiglia Capretti" [The vineyard Pusterla reborn and returns to the family Capretti.] (in Italian). Bresciaoggi.

- ↑ "Un bianco ultracentenario nel cuore di Brescia." [A centuries-old white wine in the heart of Brescia.]. slowfood.it (in Italian). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "RSY Lombardia-Arrivals and nights spent by guests in accommodation establishments, by type of resort and by type of establishment. Total accommodation establishments. Part III. Tourist resort. Year 2003". asr-lombardia.it. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Alessandra Troncana (March 27, 2014). "Turismo, Garda superstar Iseo e Franciacorta in calo" (in Italian). Corriere della Sera.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "La metro di Brescia apre sabato 2 marzo" [The Brescia Metro opens 2 March]. CityRailways.it (in Italian). 5 February 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Mappa della linea metropolitana" (PDF) (in Italian). Brescia Mobilitá. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ↑ Francesco Di Maio (April 2008). "Automation in a medium-sized city". Railway Gazette International.

- ↑ "Parte la metro! 2 marzo 2013" [The Metro goes! 2 March 2013] (in Italian). Brescia Mobilitá. 5 February 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-11.

- ↑ Official Mille Miglia website

- ↑ "Bethlehem Municipality". www.bethlehem-city.org. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- ↑ Massimo Tedeschi (2008). Il palazzo e la città. Storia del Consiglio comunale di Brescia (1946-2006) (in Italian). Brescia: Grafo edizioni.

- ↑ "Bouaké official website" (in French). mairiebke.e-monsite.com. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ "Official website of the UVICOCI-Union des Villes et Communes de Côte d'ivoire" (in French). Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ "Städtepartnerschaften und Internationales". Büro für Städtepartnerschaften und internationale Beziehungen (in German). Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "Press coverage of the Municipality of Brescia" (in Italian). servizi.comune.brescia.it. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ 友好城市 (Friendly cities), 市外办 (Foreign Affairs Office), 2008-03-22. (Translation by Google Translate.)

- ↑ 国际友好城市一览表 (International Friendship Cities List), 2011-01-20. (Translation by Google Translate.)

- ↑ 友好交流 (Friendly exchanges), 2011-09-13. (Translation by Google Translate.)

- Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

- "Brescia", Hand-book for Travellers in Northern Italy (16th ed.), London: John Murray, 1897, OCLC 2231483

- Published in the 20th century

- Edward Hutton (1912), "Brescia", The Cities of Lombardy, New York: Macmillan Co.

- "Brescia", Northern Italy (14th ed.), Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1913

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Brescia. |

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brescia. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Brescia. |

- Brescia Tourism official site: useful information,guide destination and hotel, airport

- University of Brescia official site

- Catholic University of Brescia

- Just some news about Brescia

- Photo Gallery (Italian)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||