Brahmagupta–Fibonacci identity

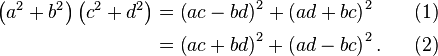

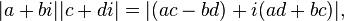

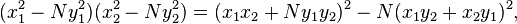

In algebra, the Brahmagupta–Fibonacci identity or simply Fibonacci's identity (and in fact due to Diophantus of Alexandria) says that the product of two sums each of two squares is itself a sum of two squares. In other words, the set of all sums of two squares is closed under multiplication. Specifically:

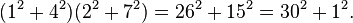

For example,

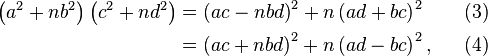

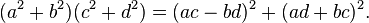

The identity is a special case (n = 2) of Lagrange's identity, and is first found in Diophantus. Brahmagupta proved and used a more general identity (the Brahmagupta identity), equivalent to

showing that the set of all numbers of the form x2 + y2 is closed under multiplication.

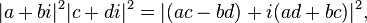

Both (1) and (2) can be verified by expanding each side of the equation. Also, (2) can be obtained from (1), or (1) from (2), by changing b to −b.

This identity holds in both the ring of integers and the ring of rational numbers, and more generally in any commutative ring.

In the integer case this identity finds applications in number theory for example when used in conjunction with one of Fermat's theorems it proves that the product of a square and any number of primes of the form 4n + 1 is also a sum of two squares.

History

The identity is actually first found in Diophantus' Arithmetica (III, 19), of the third century A.D. It was rediscovered by Brahmagupta (598–668), an Indian mathematician and astronomer, who generalized it (to the Brahmagupta identity) and used it in his study of what is now called Pell's equation. His Brahmasphutasiddhanta was translated from Sanskrit into Arabic by Mohammad al-Fazari, and was subsequently translated into Latin in 1126.[1] The identity later appeared in Fibonacci's Book of Squares in 1225.

Related identities

Analogous identities are Euler's four-square related to quaternions, and Degen's eight-square derived from the octonions which has connections to Bott periodicity. There is also Pfister's sixteen-square identity, though it is no longer bilinear.

Relation to complex numbers

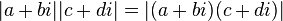

If a, b, c, and d are real numbers, this identity is equivalent to the multiplication property for absolute values of complex numbers namely that:

since

by squaring both sides

and by the definition of absolute value,

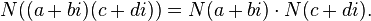

Interpretation via norms

In the case that the variables a, b, c, and d are rational numbers, the identity may be interpreted as the statement that the norm in the field Q(i) is multiplicative. That is, we have

and also

Therefore the identity is saying that

Application to Pell's equation

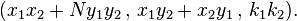

In its original context, Brahmagupta applied his discovery (the Brahmagupta identity) to the solution of Pell's equation, namely x2 − Ny2 = 1. Using the identity in the more general form

he was able to "compose" triples (x1, y1, k1) and (x2, y2, k2) that were solutions of x2 − Ny2 = k, to generate the new triple

Not only did this give a way to generate infinitely many solutions to x2 − Ny2 = 1 starting with one solution, but also, by dividing such a composition by k1k2, integer or "nearly integer" solutions could often be obtained. The general method for solving the Pell equation given by Bhaskara II in 1150, namely the chakravala (cyclic) method, was also based on this identity.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ George G. Joseph (2000). The Crest of the Peacock, p. 306. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00659-8.

- ↑ John Stillwell (2002), Mathematics and its history (2 ed.), Springer, pp. 72–76, ISBN 978-0-387-95336-6