Boston and Maine Corporation

| Boston and Maine Corporation | |

|---|---|

| |

|

B&M 1916 system map | |

| Reporting mark | BM |

| Locale |

Maine Massachusetts New Hampshire New York Vermont |

| Dates of operation | 1836–1983 |

| Successor | Guilford Transportation Industries |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 2,077 mi (3,343 km) |

| Headquarters | Boston, Massachusetts |

The Boston and Maine Corporation (reporting mark BM), known as the Boston and Maine Railroad (B&M), was a former U.S. Class I railroad in northern New England. It became part of what is now the Pan Am Railways network in 1983.

At the end of 1970 B&M operated 1,515 route-miles (2,438 km) on 2,481 miles (3,993 km) of track, not including Springfield Terminal. That year it reported 2744 million ton-miles of revenue freight and 92 million passenger-miles.

History

The Boston & Maine Railroad (B&M) grew for the most part by acquisition, not by construction. The oldest component of the B&M was the 25-mile (40 km) route between Boston and Lowell, Massachusetts, opened by the Boston & Lowell Railroad (B&L) on June 24, 1835, but not acquired until much later. The B&M's 19th century history consists of four distinct routes.[1]

Portland Division

.jpg)

B&M's earliest corporate predecessor was the Andover & Wilmington Railroad, opened in August 1836 from Andover, Massachusetts, south to a junction with the B&L at Wilmington, approximately 7 miles (11 km). The line was extended north 10 miles (16 km) to Bradford, on the south bank of the Merrimack River opposite Haverhill, the next year. Construction continued north, reaching South Berwick, Maine, in 1843, by which time the three companies involved (one from each state) had been consolidated using the name of the New Hampshire company, Boston & Maine Railroad (B&M). At South Berwick, the B&M connected with the Portland, Saco & Portsmouth Railway (PS&P), opened in 1842 between the cities of its name and leased in 1847 jointly to the B&M and the Eastern Railroad (Boston to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, opened in 1840).[1]

In 1845, dissatisfied with using the B&L, the B&M opened its own line from North Wilmington through Reading to Boston. There followed a boom period of railroad construction in eastern Massachusetts. Towns not situated along a railroad wanted one; towns already situated along a railroad wanted a second one, for the benefits of competition. Each of the three major companies — B&M, B&L, and Eastern — bought up smaller railroads as they built to keep the other two railroads from getting a hold of them. Soon the B&L had branches from Wilmington to Lawrence and from Lowell to Salem; the Eastern had a branch from Salem to Lawrence, plus several branches to coastal towns east of its main line; and the B&M had branches from Andover to Lowell and from Wakefield to Newburyport and to Peabody (the Eastern soon got the last one, giving it a nearly useless branch from Peabody to Wakefield).[1]

Competition between the B&M and the Eastern for Boston-Portland traffic was fierce. The Eastern route was a few miles shorter but reached Boston by a ferry from East Boston until 1854, when the Eastern built a line into Boston from the north. The B&M carried most of the traffic. In 1869 the Eastern and the Maine Central Railroad (MEC) began discussions about controlling the traffic, with the upshot that the PS&P canceled the joint lease and leased itself to the Eastern, which obtained control of the MEC just about the time the B&M's own line from South Berwick reached Portland. The new lease of the PS&P, the cost of control of the MEC, and several disastrous accidents nearly exhausted the Eastern. In the early 1870s, the Eastern made merger overtures to the B&M, which was unwilling to assume the Eastern's debt. The two railroads eventually reached an agreement in 1874 to end the worst of the competition, and in 1883, B&M leased the Eastern.[1]

To further protect its access to Maine, the B&M leased the Worcester, Nashua & Rochester Railroad (WN&R) in 1886; B&M already controlled the Portland & Rochester Railroad. (The Boston & Albany Railroad (B&A) did not want the Old Colony Railroad (OC) to get the WN&R; the B&M did not want the B&A to get it; and the B&L did not want the B&M to get it.)[1]

New Hampshire Division

Lowell, Massachusetts, was one of America's first industrial cities, combining the power of a falls in the Merrimack River with power textile loom technology. It began its rise in 1822, and it needed year-round transportation to Boston. The Middlesex Canal, which had opened in 1803 from Boston to the Merrimack River, froze in the winter, and the roads were inadequate. The B&L was built parallel to the canal and soon superseded it.[1]

In 1838, three years after the B&L opened, the Nashua & Lowell Railroad (N&L) began operating from Lowell north alongside the Merrimack River to Nashua, New Hampshire, a distance of 18 miles (29 km). By 1850, the N&L included branches west to Ayer, Massachusetts, and Wilton, New Hampshire, both intended primarily to block construction by the Fitchburg Railroad. In 1857, the B&L and N&L agreed to operate as a unit.[1]

By then another textile mill city, Manchester, New Hampshire, was growing north of Nashua. The Manchester & Lawrence Railroad (M&L) linked Manchester with Lawrence, Massachusetts, on the B&M, competing with the Concord Railroad-N&L-B&L route to Boston. The five railroads involved formed a pooling agreement, but then the Concord leased the M&L. The B&L proposed consolidation with the N&L and the Concord; the B&M opposed such a move. In 1869, the Great Northern Railroad was chartered. It was to include the three railroads plus the Northern (Concord, New Hampshire-White River Junction, Vermont). It required the approval of the New Hampshire legislature, which it did not get. The B&L was equally unsuccessful with a proposal to consolidate with the Fitchburg, and it had a falling out with the N&L.[1]

In 1880, the B&L leased the N&L and acquired control of the Massachusetts Central, under construction between Boston and Northampton, Massachusetts, on the Connecticut River. In 1884, it leased the Northern and the Boston, Concord & Montreal Railroad, acquired control of the St. Johnsbury & Lake Champlain, and came head to head with the Concord Railroad (Nashua-Concord, New Hampshire), kicking off a railroad war in the legislature and courts of New Hampshire. The B&L leased itself to the B&M in 1887, and let the B&M (which was incorporated in New Hampshire) do battle with the Concord Railroad.[1]

The B&M and the Concord eventually reached accord, primarily because the B&M had the Concord surrounded, except for one poorly built branch from Nashua to Concord, Massachusetts, where it connected with the Fitchburg Railroad and the OC. In 1895 the B&M, which by then had acquired control of the Concord & Montreal [C&M] (the consolidation of the Concord and the Boston, Concord & Montreal), leased the C&M and became the dominant railroad in New Hampshire, as it was in southern Maine, through control of the MEC.[1]

Fitchburg Division

B&M's line to the west was built by several different agencies over a period of 30 years. The Fitchburg Railroad was opened from Boston to Fitchburg, Massachusetts, 50 miles (80 km) northwest, in 1845. It soon acquired several branches but did not choose to extend its line to the west.[1] The Vermont & Massachusetts built west from Fitchburg to the Connecticut River at Grout's Corner, near Greenfield, then turned north, reaching Brattleboro, Vermont, in 1850.[1]

The grain of most of New England's topography runs north and south, and any railroad west from Boston has to cross two ranges of hills, the southern extensions of the White Mountains of New Hampshire and the Green Mountains of Vermont. The Western Railroad from Worcester to Albany, New York, crossed these ridges in 1840 and 1841, with the expected steep grades.[1] As early as 1819, there was a proposal for a canal across northern Massachusetts, using a tunnel to penetrate Hoosac Mountain, which stood between the valleys of the Deerfield and Hoosic rivers. The proposal for a canal became a proposal for a railroad to connect Boston with the Great Lakes at Oswego or Buffalo, New York. The tunnel was begun in 1851.[1]

The Troy & Greenfield Railroad (T&G) was built west from Greenfield to the Hoosac Tunnel by the state of Massachusetts and was leased to the Fitchburg and the Vermont & Massachusetts (V&M) in 1868. In 1870 the Vermont & Massachusetts sold its Grout's Corner-Brattleboro line to the Rutland Railway. The Troy & Boston Railroad (T&B) was opened in the early 1850s from Troy, New York, north to the Hoosic River, then east and south to connections at Eagle Bridge and White Creek with two railroads north to Rutland, Vermont. In 1857, it leased the latter of these, the Western Vermont Railroad from Bennington to Rutland, Vermont. (In 1867 at the expiration of the lease, the Bennington & Rutland, successor to the Western Vermont, seized several dozen T&B locomotives and cars and held them for ransom, alleging damage to the line while under T&B operation.)[1] By 1859 the T&B had joined up with the Southern Vermont (8 miles (13 km) across the southwest corner of Vermont), and the 7-mile-long (11 km) western portion of the T&G to form a route from Troy to North Adams, Massachusetts. Two petitions before the Massachusetts legislature in 1873, to allow consolidation of the Fitchburg, V&M, T&G, Hoosac Tunnel (then nearly complete), and the T&B, and to consolidate the B&L and the Fitchburg, led to a legislative committee proposal to consolidate all of them. The railroads all but rejected the proposal; the sole change resulting from the proposal was that the Fitchburg leased the V&M.[1]

As the Hoosac Tunnel neared completion in 1875, two other railroads were proposed: the Massachusetts Central west from Boston, approximately halfway between Fitchburg-V&M and the B&A lines, to a connection with the T&G; and the Boston, Hoosac Tunnel & Western Railroad (BHT&W), from the Hoosac Tunnel to Oswego, New York. The Massachusetts Central ran out of breath when it reached the Connecticut River at Northampton; the BHT&W was built from the Vermont-Massachusetts state line near Williamstown, Massachusetts, parallel to the T&B as far as Johnsonville, New York, and crossing it several times, then west to Mechanicville and Rotterdam, New York. The T&B made a freight traffic agreement with the New York Central Railroad (NYC) and the Fitchburg, and the BHT&W did the same with the Delaware & Hudson Railway (D&H), the Erie Railroad, and the Fitchburg.[1]

The Fitchburg wanted to gain control of the Hoosac Tunnel, and the state, which owned the tunnel, would allow that only if the Fitchburg had its own route to the Hudson River. Accordingly, in the 1880s the Fitchburg acquired the T&B, the T&G, and the BHT&W, along with branches to Worcester, Bellows Falls, Vermont, and Saratoga Springs, New York. In 1899, the NYC was considering leasing either the B&A or the Fitchburg or both to gain access to Boston. NYC doubted it could get state approval to lease both and chose the B&A. The B&M offered to lease the Fitchburg and in 1900 it did so.[1]

Connecticut River line

The Connecticut River Line connected with all routes running west and northwest from Boston:

- B&A at Springfield, Massachusetts;

- Massachusetts Central at Northampton;

- Fitchburg at Greenfield;

- V&M at East Northfield;

- Cheshire Railroad and Rutland at Bellows Falls, Vermont;

- Concord & Claremont at Claremont, New Hampshire;

- Northern Railroad and Central Vermont Railway (CV) at White River Junction, Vermont;

- Boston, Concord & Montreal and Montpelier & Wells River (M&WR) at Wells River, Vermont; plus

- Portland & Ogdensburg Railway and the St. Johnsbury & Lake Champlain (StJ&LC) at St. Johnsbury, Vermont.[1]

It consisted of six companies:

- Connecticut River Railroad to Springfield-East Northfield;

- V&M to Brattleboro;

- Vermont Valley to Bellows Falls;

- Sullivan County to Windsor;

- CV to White River Junction;

- Connecticut & Passumpsic Rivers Railroad from White River Junction to the Canadian border at Newport, Vermont.[1]

They were all under control of the Connecticut River Railroad (except for CV), as was the St. Johnsbury & Lake Champlain Railroad.[1]

By 1893, the lines north of White River Junction had been leased to the B&M, and the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad (NH) was ready to lease what remained, but during the few months of control of the B&M by the Philadelphia & Reading Railway (P&R), A. A. MacLeod, president of the P&R, secured control of the Connecticut River Railroad (CRRR), leased it to the B&M, and signed an agreement with the NH to divide New England along the line of the B&A. (NH already had several branches that reached north of the B&A almost to the New Hampshire border; B&M had none south of the B&A.)[1]

Twentieth century

In the early twentieth century B&M and its controlled lines reached from Boston west to the Hudson River at Troy and Mechanicville, New York, and the Mohawk River at Rotterdam Junction; northwest to Lake Champlain at Maquam, Vermont; north to Sherbrooke and Lime Ridge, Quebec; and northeast to Vanceboro and Eastport, Maine. East of the Connecticut River, north of the B&A, and south of the Canadian border there were only two railroads of any consequence not under B&M control: the Bangor & Aroostook Railroad and the Grand Trunk Railway route from Montreal and Sherbrooke to Portland, Maine.[1]

The NH, expanding under the leadership of Charles S. Mellen, acquired control of the B&M in 1907. In 1914 the NH's B&M stock was placed in the hands of trustees for eventual sale, and that same year B&M sold its MEC stock. B&M was placed in receivership in 1916.[1]

In 1919, the B&M simplified its corporate structure slightly by consolidating with itself the Fitchburg, B&L, CRRR and Concord & Montreal railroads. B&M returned to independent operation several roads it had been operating: Suncook Valley Railroad in 1924, StJ&LC in 1925, and M&WR in 1926. Also in 1926 B&M leased its lines between Wells River, Vermont, and Sherbrooke, Quebec, to the Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) and CP subsidiary Quebec Central Railway. About the same time B&M abandoned some of the weakest of its redundant branch lines.[1]

B&M opened a new North Station in Boston in 1928, replacing the adjacent B&M, B&L and Fitchburg stations, which had been operated as a unit. In 1930, B&M acquired control of the Springfield Terminal Railway (ST), an electric interurban line between Charlestown, New Hampshire and Springfield, Vermont, a length of 6.5 miles (10.5 km).[2]

From 1932 to 1952, B&M shared offices with MEC in a voluntary arrangement that provided many of the benefits of consolidation or merger. B&M continued to abandon or sell branch lines in order to stay solvent. B&M disposed of its interest in the Mount Washington Cog Railway in 1939, followed by a series of branch lines sold to Samuel M. Pinsly to form several short lines:

- the branch from Mechanicville to Saratoga, New York, became the Saratoga & Schuylerville in 1945;

- the Rochester, New Hampshire-Westbrook, Maine, line became the Sanford & Eastern in 1949; and

- the Concord-Claremont, New Hampshire, branch became the Claremont & Concord Railroad in 1954.[1]

In 1946, B&M purchased the Connecticut & Passumpsic Rivers Railroad south of Wells River, Vermont; CP and its subsidiaries purchased the line north of Wells River. Floods in 1936 and a hurricane in 1938 caused the abandonment of several branches.[1]

B&M dieselized quickly, except for suburban passenger trains, and it was an early user of Centralized Traffic Control. In 1950 it was a well-run, progressive railroad — in a region that was losing its heavy industry and beginning to build interstate superhighways. In 1956, Patrick B. McGinnis became president of the B&M, bringing in a new image — not just blue replacing maroon on the locomotives and cars but a new way of doing things: deficits, deferred maintenance, and kickbacks on the sale of B&M's streamlined passenger cars, which ultimately culminated in a prison sentence that ended his career in railroading. B&M amassed the world's largest fleet of Budd Rail Diesel Cars (RDCs), using them for all passenger service except the New York-Montreal trains operated in conjunction with the NH and CV, and by the mid-1960s only suburban passenger service remained, operated for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA).[1]

McGinnis's managerial style had left the NH's finances in a perilous state; earnings for 1955 were less than half of what McGinnis had claimed. McGinnis did the same damage to B&M, which by 1958, was posting record deficits that would continue unabated. B&M asked to be included in the Norfolk & Western Railway (N&W), but N&W was reluctant to take on what was rapidly becoming a charity case. On March 23, 1970, B&M declared bankruptcy. By the end of the year, B&M's trustees had chosen John W. Barriger III to be CEO. Barriger retired at the end of 1972, having made a start of rerailing the B&M.[1]

Rather than split B&M among its connections or ask for inclusion in Conrail, B&M's trustees decided to reorganize independently. Under the leadership of Alan Dustin, the B&M bought new locomotives, rebuilt its track, and changed its attitude. The revived B&M went after new business and expanded its operations. It sold the tracks and rolling stock to MBTA in 1975, but retained freight rights on those lines and continued to operate the trains for MBTA. In 1977 it assumed operation of commuter trains on the former NH and B&A lines out of Boston's South Station. In 1982 it bought several Conrail lines in Massachusetts and Connecticut,[1] and began operating coal trains and piggyback service.

Guilford

The revived B&M was purchased in 1983 for $24 million by Timothy Mellon's Guilford Transportation Industries, which had bought the MEC in 1981 and in 1984 would buy the D&H. Guilford began operating the three railroads as a unified system, selling unprofitable lines, closing redundant yards and shops, eliminating jobs, and essentially undoing Dustin's revitalization projects.[3] Mellon, heir to the Mellon Bank fortune whose motives were largely driven by ideology and profit, had little understanding of the railroad industry and its labor quirks.[3] Mellon's draconian management style resulted in railroad employees going on strike in 1986 and 1987. As a cost-saving tactic, Mellon leased most of the B&M and the MEC to the ST to take advantage of short-line work rules that raised profits for Guilford but cut employee pay in half.

Track degenerated to the point that Amtrak discontinued the Montrealer, which operated on B&M rails between Springfield, Massachusetts and Windsor, Vermont. The CV later acquired and rebuilt the Brattleboro-Windsor line, and Amtrak restored the Montrealer, rerouting it on CV rails south of Brattleboro.[1] Additional drastic cost cutting occurred in 1990 with the closure of B&M's Mechanicville, New York, site, the largest rail yard and shop facilities on the B&M system. This closure removed most freight traffic from the former Fitchburg Division line through Hoosac Tunnel.[3] B&M's problem for years had been that its routes were so short that its share of revenue on a freight move was small; those routes became approximately 175 miles (282 km) shorter under Mellon's ownership.[1]

Pan Am Railways

For most of its existence, Guilford had about as much success with B&M as it has had with MEC: none. This was due more to mismanagement and a lack of understanding of how a railroad works than questionable traffic loads.[1] Guilford changed its name to Pan Am Railways (PAR) in 2006. Technically, B&M Corporation still exists but only as a non-operating ward of PAR. B&M owns the property (and also employs its own railroad police), while ST operates the trains and performs maintenance. This complicated operation is due to more favorable labor agreements under ST rules.

Pan Am entered a joint venture with Norfolk Southern Railway (NS) in April 2009 to form Pan Am Southern (PAS). PAR transferred to the joint venture its 155-mile (249 km) main line track that runs between Mechanicville, New York, and Ayer, Massachusetts. This route includes the B&M's Hoosac Tunnel and Fitchburg line as far as Willows, Massachusetts. Also included are 281 miles (452 km) of secondary and branch lines, including trackage rights, in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, and Vermont. NS transferred cash and other property valued at $140 million to the joint venture, $87.5 million of which was expected to be invested within a three-year period in capital improvements on the Patriot Corridor, such as terminal expansions, track and signal upgrades. ST provides all railroad services for the joint venture, again to keep costs down.

Service at B&M's former yard in Mechanicville, New York, was restored in January 2012 under PAS.[4]

Passenger trains

New York City trains served Grand Central Terminal, except where noted. Boston trains served North Station.[5]

- Alouette – Boston - Montreal

- Ambassador – Boston - Montreal

- Cheshire – Boston - Fitchburg - Bellows Falls

- Day White Mountains – New York City - Berlin, NH

- East Wind – Washington, DC - New York City (Penn Station) - Bar Harbor

- Flying Yankee – Boston - Bangor

- Gull – Boston - Halifax

- Kennebec – Boston - Bangor

- Minute Man – Boston - Troy, NY

- Montrealer/Washingtonian – New York City - Montreal

- Mountaineer – Boston - Littleton, NH (summer only)

- Night White Mountains – New York City - Bretton Woods, NH

- Pine Tree – Boston - Bangor

- Red Wing – Boston - Montreal (night train)

- State of Maine – New York City - Worcester - Bangor (night train)

Gallery

-

1898 B&M System map

-

Woodburytype of 0-4-0 Achilles, Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1871

-

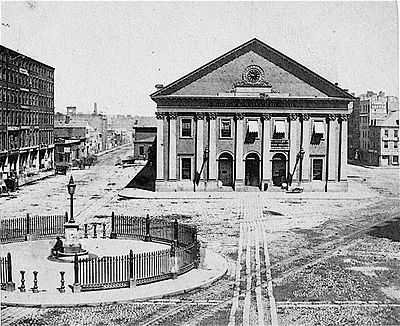

B&M depot, Boston, circa 19th

-

Wells, Maine Station, circa 1910

-

B&M train passing through Saco, Maine, circa 1879

-

B&M yard, Keene, New Hampshire, circa 1916

-

Littleton, Massachusetts Station, circa 1910

-

B&M boxcar with faded interlocking "B" and "M" logo used during the McGinnis era, circa 2005

-

B&M advertisement, circa 1905

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 Drury, George H. (1994). The Historical Guide to North American Railroads: Histories, Figures, and Features of more than 160 Railroads Abandoned or Merged since 1930. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 365–371. ISBN 0-89024-072-8.

- ↑ Springfield Terminal Railroad map

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Belden, Tom (May 6, 1990). "An Investor Believes He's On Track; Banking Heir Timothy D. Mellon Has Poured Millions Into Regional Railroads; He's Also Stirred Controversy". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ↑ Post, Paul (March 24, 2012). "Boom II: Overshadowed by GlobalFoundries, new rail hub could spur unprecedented growth along Route 67 corridor in Stillwater". The Saratogian. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ↑ Run-Through Passenger Trains in New England - Far Acres Farm

- Edward Appleton, Massachusetts Railway Commissioner (1871). "History of the Railways of Massachusetts".

- Karr, Ronald D. (1995). The Rail Lines of Southern New England - A Handbook of Railroad History. Branch Line Press. ISBN 0-942147-02-2.

- Karr, Ronald D. (1994). Lost Railroads New England. Branch Line Press. ISBN 0-942147-04-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boston and Maine Railroad. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Boston and Maine Railroad. |

- Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society

- July 1, 1923 Official List - Officers, Agents and Stations

- Boston & Maine All-Time Pre-Guilford Diesel Roster

| ||||||