Bosnian Church

| Bosnian Church Crkva bosanska/Црква босанска | |

|---|---|

| |

| Classification | Heretical church |

| Governance | Banate of Bosnia, Bosnian Kingdom |

| Origin | 12th century |

| Other name(s) | Crkva Dobrih Bošnjana |

The Bosnian Church (Bosnian: Crkva bosanska/Црква босанска Latin: Ecclesia bosniensis) was a Christian church in Medieval Bosnia that was independent of and considered heretical by both the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox hierarchies. Historians have traditionally connected the church with the Bogomils, although this has been challenged. Adherents of the church called themselves simply Krstjani ("Christians") or Dobri Bošnjani ("Good Bosnians"). The church's organization and beliefs are poorly understood, because few if any records were left by church members, and the church is mostly known from the writings of outside sources, primarily Roman Catholic ones.

History

Christian missions emanating from Rome and Constantinople had since the ninth century pushed into the Balkans and firmly established Catholicism in Croatia and most of Dalmatia, while Orthodoxy came to prevail in Bulgaria, Macedonia, and eventually most of Serbia. Bosnia, lying in between, remained a no-man's land due to its mountainous terrain and poor communications.[1]

No accurate figures exist as to the numbers of adherents of the two churches. The Bosnian Church coexisted uneasily with Roman Catholicism for much of the later Middle Ages. Part of the resistance of the Bosnian Church was political. During the 14th century, the Roman Church placed Bosnia under a Hungarian bishop, and the schism may have been motivated by a desire for independence from Hungarian domination. Several Bosnian rulers were Krstjani, but some of them embraced Roman Catholicism for political reasons.

Outsiders accused the Bosnian Church of links to the Bogomils, a stridently dualist sect of dualist-gnostic Christians heavily influenced by the Manichaean Paulician movement and also to the Patarene heresy (itself only a variant of the same belief system of Manichean-influenced dualism). The Bogomil heretics at one point mainly were centered in Bulgaria and are now known by historians as the direct progenitors of the Cathars. The Inquisition reported the existence of a dualist sect in Bosnia in the late 15th century and called them "Bosnian heretics", but this sect was according to some historians most likely not the same as the Bosnian Church. The historian Franjo Rački wrote about this in 1869 based on Latin sources but the Croatian scholar Dragutin Kniewald in 1949 established the credibility of the Latin documents in which the Bosnian Church is described as heretical.[2] It is thought today that the Bosnian dualists, who were persecuted by both the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, were predominantly converted to Islam thus contributing to the ethnogenesis of the modern-day Bosniaks. The Bosnian Church was dualist in character, and so was neither a schismatic Catholic nor Orthodox Church.[3] According to Mauro Orbini (d.1614), the Patarenes and the Manicheans[4] were two Christian religious sects in Bosnia. The Manicheans had a bishop called djed and priests called strojnici (strojniks), the same titles ascribed to the leaders of the Bosnian Church.[5] The church left a few traditions by those who converted to Islam, one of which is having mosques built out of wood because many Bogomilian churches were primarily built of wood. Another tradition is having the imam stay at the grave of a deceased person which is something not found in other Islamic communities.

Some historians reckon that the Bosnian Church had largely disappeared before the Turkish conquest in 1463. Other historians dispute a discrete terminal point.

The religious centre of the Bosnian Church was located in Moštre, near Visoko, where the house of krstjani was founded.[6]

Characteristics

The Church had its own bishop and used the Slavic language in liturgy. The bishop was called djed (lit. "grandfather"), and had a council of twelve men called strojnici. The monasteries were called hiža (lit. "house"), and the heads of monasteries were often called gost (lit. "guest") and served as strojnici.

The Church was mainly composed of monks in scattered monastic houses. It had no territorial organization and it did not deal with any secular matters other than attending people's burials. It did not involve itself in state issues very much. Notable exceptions were when King Stephen Ostoja of Bosnia, a member of the Bosnian Church himself, had a djed as an advisor at the royal court between 1403 and 1405, and an occasional occurrence of a krstjan elder being a mediator or diplomat.

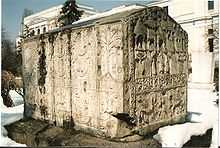

The monumental tombstones called stećci (plural) / stećak (singular) that appeared in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina are identified with the Bosnian Church.

Bosnian Church scholarship

The phenomenon of Bosnian medieval Christians has been attracting scholars' attention for centuries, but it was not until the latter half of the 19th century that the most important monograph on the subject, "Bogomili i Patareni" (Bogomils and Patarens), 1870, by eminent Croatian historian Franjo Rački, had been published. Rački argued that the Bosnian Church was essentially Gnostic and Manichaean in nature. This interpretation has been accepted, expanded and elaborated upon by a host of later historians, most prominent among them being Dominik Mandić, Sima Ćirković, Vladimir Ćorović, Miroslav Brandt and Franjo Šanjek. However, a number of other historians (Leon Petrović, Jaroslav Šidak, Dragoljub Dragojlović, Dubravko Lovrenović, and Noel Malcolm) stressed theologically the impeccably orthodox character of Bosnian Christian writings and claimed that for the explanation of this phenomenon suffices the relative isolation of Bosnian Christianity, which retained many archaic traits predating the East-West Schism in 1054.

Conversely, the American historian of the Balkans, Prof. John Fine, does not believe in the dualism of the Bosnian Church at all.[7] Though he represents his theory as a "new interpretation of the Bosnian Church", his view is very close to J. Šidak's early theory and several other scholars before him.[8] He believes that there could well have been heretical groups alongside of the Bosnian Church, however, the church itself emanated from Catholicism gone astray.

See also

- Christianity

- Rodnovery

- Stećci

- Islam in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Pomaks

- Bogomilism

- Paulicianism

References

- ↑ Pinson, Mark (1994). The Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina: Their Historic Development from the Middle Ages to the Dissolution of Yugoslavia. Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-932885-09-8.

- ↑ Denis Bašić. The roots of the religious, ethnic, and national identity of the Bosnian-Herzegovinan [sic] Muslims. University of Washington, 2009, 369 pages (p. 194).

- ↑ Denis Bašić, p. 186.

- ↑ The Paulicians and Bogomils have been confounded with the Manichaeans. L. P. Brockett, The Bogomils of Bulgaria and Bosnia - The Early Protestants of the East. Appendix II, http://www.reformedreader.org/history/brockett/bogomils.htm

- ↑ Mauro Orbini. II Regno Degli Slav: Presaro 1601, p.354 and Мавро Орбини, Кралство Словена, p. 146.

- ↑ Old town Visoki declared as national monument. 2004.

- ↑ Fine, John. The Bosnian Church: Its Place in State and Society from the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century: A New Interpretation. London: SAQI, The Bosnian Institute, 2007. ISBN 0-86356-503-4

- ↑ Denis Bašić, p.196.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bosnian Church. |