Bose–Hubbard model

The Bose–Hubbard model gives an approximate description of the physics of interacting bosons on a lattice. It is closely related to the Hubbard model which originated in solid-state physics as an approximate description of superconducting systems and the motion of electrons between the atoms of a crystalline solid. The name Bose refers to the fact that the particles in the system are bosonic; the model was first introduced by Gersch H., Knollman G [1] in 1963, The Bose–Hubbard model can be used to study systems such as bosonic atoms on an optical lattice. In contrast, the Hubbard model applies to fermionic particles such as electrons, rather than bosons. Furthermore, it can also be generalized and applied to Bose–Fermi mixtures, in which case the corresponding Hamiltonian is called the Bose–Fermi–Hubbard Hamiltonian.

The Hamiltonian

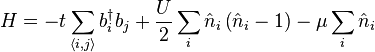

The physics of this model is given by the Bose–Hubbard Hamiltonian:

.

.

Here i is summed over all lattice sites, and  denotes summation over all neighboring sites i and j..

denotes summation over all neighboring sites i and j..  and

and  are bosonic creation and annihilation operators.

are bosonic creation and annihilation operators.  gives the number of particles on site i. Parameter

gives the number of particles on site i. Parameter  is the hopping matrix element, signifying mobility of bosons in the lattice. Parameter

is the hopping matrix element, signifying mobility of bosons in the lattice. Parameter  describes the on-site interaction, if

describes the on-site interaction, if  it describes repulsive interaction, if

it describes repulsive interaction, if  then the interaction is attractive.

then the interaction is attractive.  is the chemical potential.

is the chemical potential.

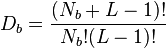

The dimension of the Hilbert space of the Bose–Hubbard model grows exponentially with respect to the number of particles N and lattice sites L. It is given by:

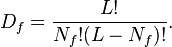

while that of Fermi–Hubbard Model is given by:

while that of Fermi–Hubbard Model is given by:

The different results stem from different statistics of fermions and bosons.

For Bose–Fermi mixtures, the corresponding Hilbert space of the Bose–Fermi–Hubbard model is simply the tensor product of Hilbert spaces of the bosonic model and the fermionic model.

The different results stem from different statistics of fermions and bosons.

For Bose–Fermi mixtures, the corresponding Hilbert space of the Bose–Fermi–Hubbard model is simply the tensor product of Hilbert spaces of the bosonic model and the fermionic model.

Phase diagram

At zero temperature, the Bose–Hubbard model (in the absence of disorder) is in either a Mott insulating (MI) state at small  , or in a superfluid (SF) state at large

, or in a superfluid (SF) state at large  .[2] The Mott insulating phases are characterized by integer boson densities, by the existence of an energy gap for particle-hole excitations, and by zero compressibility. In the presence of disorder, a third, ‘‘Bose glass’’ phase exists. The Bose glass phase is characterized by a finite compressibility, the absence of a gap, and by an infinite superfluid susceptibility.[3] It is insulating despite the absence of a gap, as low tunneling prevents the generation of excitations which, although close in energy, are spatially separated.

.[2] The Mott insulating phases are characterized by integer boson densities, by the existence of an energy gap for particle-hole excitations, and by zero compressibility. In the presence of disorder, a third, ‘‘Bose glass’’ phase exists. The Bose glass phase is characterized by a finite compressibility, the absence of a gap, and by an infinite superfluid susceptibility.[3] It is insulating despite the absence of a gap, as low tunneling prevents the generation of excitations which, although close in energy, are spatially separated.

Implementation in optical lattices

Ultracold atoms in optical lattices are considered a standard realization of the Bose Hubbard model. The ability to tune parameters of the model using simple experimental techniques, lack of lattice dynamics, present in electronic systems provides very good conditions for experimental study of this model.[4][5]

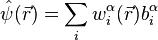

The hamiltonian in Second quantization formalism describing a gas of ultracold atoms in the optical lattice potential is of the form :

![H= \int {\rm d}^3 r \! \left[ \hat\psi^\dagger(\vec r) \left ( -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 +V_{\rm latt.}(x) \right) \hat\psi(\vec r)

+ \frac{g}{2}\hat \psi^\dagger(\vec r)\hat\psi^\dagger(\vec r)\hat\psi(\vec r)\hat\psi(\vec r) - \mu \hat{\psi}^\dagger(\vec r)\hat\psi(\vec r)\right]](../I/m/f205bd683e5166fb31c619b7d0e369fb.png) ,

,

where,  is the optical lattice potential, g is interaction amplitude (here contact interaction is assumed),

is the optical lattice potential, g is interaction amplitude (here contact interaction is assumed),  is a chemical potential. Standard tight binding approximation (see this article for details)

is a chemical potential. Standard tight binding approximation (see this article for details)  yields the Bose-Hubbard hamiltonians if one assumes additionally

that

yields the Bose-Hubbard hamiltonians if one assumes additionally

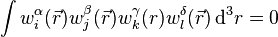

that  except for case

except for case  . Here

. Here  is a Wannier function for a particle in an optical lattice potential localized around site i of the lattice and for

is a Wannier function for a particle in an optical lattice potential localized around site i of the lattice and for  th Bloch band.[6]

th Bloch band.[6]

Subtleties and approximations

The tight-binding approximation simplifies significantly the second quantization hamltonian, introducing several limitations in the same time:

- Parameters U and J may in fact depend on density, as neglected terms are in fact not exactly zero; instead of one parameter U, the interaction energy of n particles may be described by

close, but not equal to U [6]

close, but not equal to U [6] - When considering fast lattice dynamics, additional terms should be added to the Bose-Hubbard hamiltonian, so that the Time-dependent Schrödinger equation was obeyed. They come from dependence on time of Wannier functions.[7][8]

Experimental results

Quantum phase transitions in the Bose–Hubbard model were experimentally observed by Greiner et al.[9] in Germany. Density dependent interaction parameters  were observed by I.Bloch's group [10]

were observed by I.Bloch's group [10]

Further applications of the model

The Bose–Hubbard model is also of interest to those working in the field of quantum computation and quantum information. Entanglement of ultra-cold atoms can be studied using this model.[11]

Numerical simulation

In the calculation of low energy states the term proportional to  means that large occupation of a single site is improbable, allowing for truncation of local Hilbert space to states containing at most

means that large occupation of a single site is improbable, allowing for truncation of local Hilbert space to states containing at most  particles. Then the local Hilbert space dimension is

particles. Then the local Hilbert space dimension is  The dimension of the full Hilbert space grows exponentially with the number of sites in the lattice, therefore computer simulations are limited to the study of systems of 15-20 particles in 15-20 lattice sites. Experimental systems contain several millions lattice sites, with average filling above unity. For the numerical simulation of this model, an algorithm of exact diagonalization is presented in this paper.[12]

The dimension of the full Hilbert space grows exponentially with the number of sites in the lattice, therefore computer simulations are limited to the study of systems of 15-20 particles in 15-20 lattice sites. Experimental systems contain several millions lattice sites, with average filling above unity. For the numerical simulation of this model, an algorithm of exact diagonalization is presented in this paper.[12]

One-dimensional lattices may be treated by Density matrix renormalization group (DMRG) and related techniques such as Time-evolving block decimation (TEBD). This includes to calculate the ground state of the Hamiltonian for systems of thousands of particles on thousands of lattice sites, and simulate its dynamics governed by the Time-dependent Schrödinger equation.

Higher dimensions are significantly more difficult due to the quick growth of entanglement.[13]

All dimensions may be treated by Quantum Monte Carlo algorithms, which provide a way to study properties of thermal states of the Hamiltonian, as well as the particular the ground state.

Generalizations

Bose-Hubbard-like Hamiltonians may be derived for:

- systems with density-density interaction

- long-range dipolar interaction [14]

- systems with interaction-induced tunneling terms

[15]

[15] - internal spin structure (spin-1 Bose–Hubbard model) [16]

- disordered systems [17]

See also

- Hubbard model

- Jaynes-Cummings-Hubbard model

References

- ↑ Gersch, H.; Knollman, G. (1963). "Quantum Cell Model for Bosons". Physical Review 129 (2): 959. Bibcode:1963PhRv..129..959G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.129.959.

- ↑ Kühner, T.; Monien, H. (1998). "Phases of the one-dimensional Bose-Hubbard model". Physical Review B 58 (22): R14741. arXiv:cond-mat/9712307. Bibcode:1998PhRvB..5814741K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.58.R14741.

- ↑ Fisher, Matthew P. A.; Grinstein, G.; Fisher, Daniel S. (1989). "Boson localization and the superfluid-insulator transition". Physical Review B 40: 546–70. Bibcode:1989PhRvB..40..546F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.40.546.,

- ↑ Jaksch, D.; Bruder, C.; Cirac, J.; Gardiner, C.; Zoller, P. (1998). "Cold Bosonic Atoms in Optical Lattices". Physical Review Letters 81 (15): 3108. arXiv:cond-mat/9805329. Bibcode:1998PhRvL..81.3108J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.3108.

- ↑ Jaksch, D.; Zoller, P. (2005). "The cold atom Hubbard toolbox". Annals of Physics 315: 52. arXiv:cond-mat/0410614. Bibcode:2005AnPhy.315...52J. doi:10.1016/j.aop.2004.09.010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lühmann, D. S. R.; Jürgensen, O.; Sengstock, K. (2012). "Multi-orbital and density-induced tunneling of bosons in optical lattices". New Journal of Physics 14 (3): 033021. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/14/3/033021.

- ↑ Sakmann, K.; Streltsov, A. I.; Alon, O. E.; Cederbaum, L. S. (2011). "Optimal time-dependent lattice models for nonequilibrium dynamics". New Journal of Physics 13 (4): 043003. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/13/4/043003.

- ↑ Łącki, M.; Zakrzewski, J. (2013). "Fast Dynamics for Atoms in Optical Lattices". Physical Review Letters 110 (6). arXiv:1210.7957. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.110f5301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.065301.

- ↑ Greiner, Markus; Mandel, Olaf; Esslinger, Tilman; Hänsch, Theodor W.; Bloch, Immanuel (2002). "Quantum phase transition from a superfluid to a Mott insulator in a gas of ultracold atoms". Nature 415 (6867): 39–44. doi:10.1038/415039a. PMID 11780110.

- ↑ Will, S.; Best, T.; Schneider, U.; Hackermüller, L.; Lühmann, D. S. R.; Bloch, I. (2010). "Time-resolved observation of coherent multi-body interactions in quantum phase revivals". Nature 465 (7295): 197–201. doi:10.1038/nature09036. PMID 20463733.

- ↑ Romero-Isart, O; Eckert, K; Rodó, C; Sanpera, A (2007). "Transport and entanglement generation in the Bose–Hubbard model". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 40 (28): 8019–31. arXiv:quant-ph/0703177. Bibcode:2007JPhA...40.8019R. doi:10.1088/1751-8113/40/28/S11.

- ↑ Zhang, J M; Dong, R X (2010). "Exact diagonalization: The Bose–Hubbard model as an example". European Journal of Physics 31 (3): 591–602. arXiv:1102.4006. Bibcode:2010EJPh...31..591Z. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/31/3/016.

- ↑ Eisert, J.; Cramer, M.; Plenio, M. B. (2010). "Colloquium: Area laws for the entanglement entropy". Reviews of Modern Physics 82: 277. arXiv:0808.3773. Bibcode:2010RvMP...82..277E. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.82.277.

- ↑ Góral, K.; Santos, L.; Lewenstein, M. (2002). "Quantum Phases of Dipolar Bosons in Optical Lattices". Physical Review Letters 88 (17). arXiv:cond-mat/0112363. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88q0406G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.170406.

- ↑ Sowiński, T.; Dutta, O.; Hauke, P.; Tagliacozzo, L.; Lewenstein, M. (2012). "Dipolar Molecules in Optical Lattices". Physical Review Letters 108 (11). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.115301.

- ↑ Tsuchiya, S.; Kurihara, S.; Kimura, T. (2004). "Superfluid–Mott insulator transition of spin-1 bosons in an optical lattice". Physical Review A 70 (4). arXiv:cond-mat/0209676. Bibcode:2004PhRvA..70d3628T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.70.043628.

- ↑ Gurarie, V.; Pollet, L.; Prokof’Ev, N. V.; Svistunov, B. V.; Troyer, M. (2009). "Phase diagram of the disordered Bose-Hubbard model". Physical Review B 80 (21). arXiv:0909.4593. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..80u4519G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.214519.