Borophaginae

| Borophaginae Temporal range: 40–2.5Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Strobodon stirtoni, Cat Tooth | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Subfamily: | †Borophaginae |

| Genera | |

|

See text | |

The subfamily Borophaginae is an extinct group of canids called "bone-crushing dogs"[1] that were endemic to North America during the Oligocene to Pliocene and lived roughly 36—2.5 million years ago and existing for about 33.5 million years.[2]

Origin

The Borophaginae apparently descended from the subfamily Hesperocyoninae. The earliest and most primitive borophagine is the genus Archaeocyon, which is a small fox-sized animal mostly found in the fossil beds in western North America. The borophagines soon diversified into several major groups. They evolved to become considerably larger than their predecessors, and filled a wide range of niches in late Cenozoic North America, from small omnivores to powerful, bear-sized carnivores, such as Epicyon.[2][3]

Species

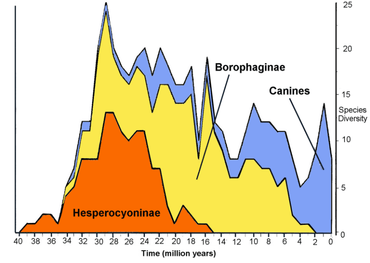

There are 66 identified Borophagine species, including 18 new ones that range from the Orellan to Blancan ages. A phylogenetic analysis of the species was conducted using cladistic methods, with Hesperocyoninae as an archaic group of canids, as the outgroup. Aside from some transitional forms, Borophaginae can be organized into four major clades: Phlaocyonini, Cynarctina, Aelurodontina, and Borophagina (all erected as new tribes or subtribes). The Borophaginae begins with a group of small fox-sized genera, such as Archaeocyon, Oxetocyon, Otarocyon, and Rhizocyon, in the Orellan through early Arikareean stages.[4] These canids reached their maximum diversity of species around 28 million years ago.

Often generically referred to as "bone-crushing dogs" for their powerful teeth and jaws, and hyena-like features (although their dentition was more primitive than that of hyenas), their fossils are abundant and widespread; in all likelihood, they were probably one of the top predators of their ecosystems.[3][5] Their good fossil record has also allowed a detailed reconstruction of their phylogeny, showing that the group was highly diverse in its heyday.[3] All Borophaginae had a small fifth toe on their rear feet (similar to the toes that bear dew claws on the front feet), where as all modern Caninae have only four toes normally.[6]

Noteworthy genera in this group are Aelurodon, Epicyon, and Borophagus (=Osteoborus). According to Xiaoming Wang, the Borophaginae played broad ecological roles that are performed by at least three living carnivoran families, Canidae, Hyaenidae, and Procyonidae.

Classification

Borophagine taxonomy, following Wang et al.[3]

- Family Canidae

(million years=in existence)

- Subfamily †Borophaginae

- †Archaeocyon 33—26 Ma, existing 7 million years

- †Oxetocyon 33—28 Ma, existing 4 million years

- †Otarocyon 34—30 Ma, existing 4 million years

- †Rhizocyon 33—26 Ma, existing 4 million years

- Tribe †Phlaocyonini 33—13 Ma, existing 20 million years

- †Cynarctoides 30—18 Ma, existing 12 million years

- †Phlaocyon 30—19 Ma,11 million years

- Tribe †Borophagini 30—3 Ma, existing 27 million years

- †Cormocyon 30—20 Ma, existing 10 million years

- †Desmocyon 25—16 Ma, existing 9 million years

- †Metatomarctus 19—16 Ma, existing 3 million years

- †Euoplocyon 18—16 Ma, existing 2 million years)

- †Psalidocyon 16—13 Ma, existing 7 million years

- †Microtomarctus 21—13 Ma, existing (7 million years

- †Protomarctus 20—16 Ma, existing (4 million years

- †Tephrocyon 16—14 Ma, existing 2.7 million years

- Subtribe †Cynarctina 20—10 Ma, existing 10 million years

- †Paracynarctus 19—16 Ma, existing 3 million years

- †Cynarctus 16—12 Ma, existing 4 million years

- Subtribe †Aelurodontina 20—5 Ma, existing 15 million years

- Subtribe †Borophagina

- †Paratomarctus 16—5 Ma, existing 11 million years

- †Carpocyon 16—5 Ma, existing 11 million years

- †Protepicyon 16—12 Ma, existing 2.7 million years

- †Epicyon 12—10 Ma, existing 2 million years

- †Borophagus (=Osteoborus) 12—5 Ma, existing (7 million years

- Subfamily †Borophaginae

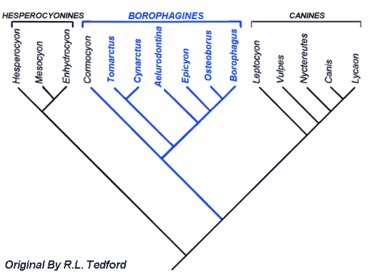

Cladogram showing borophagine interrelationships, following Wang et al., figure 141:[3]

| Canidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

References

- ↑ http://paleodb.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl?action=checkTaxonInfo&taxon_no=83323&is_real_user=1 Paleobiology Database: Borophaginae

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Postanowicz, Rebecca. "Lioncrusher's Domain: Canidae". Retrieved 2006-04-12.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Wang, Xiaoming; Richard Tedford; Beryl Taylor (1999-11-17). "Phylogenetic systematics of the borophaginae". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 243. hdl:2246/1588.

- ↑ ANMH Scientific Library, Wang, X.

- ↑ Alan Turner, "National Geographic: Prehistoric Mammals" (Washington, D.C.: Firecrest Books Ltd., 2004), pp. 112–114. ISBN 0-7922-7134-3

- ↑ Wang, Xiaoming; and Tedford, Richard H. Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. p44

Additional Reading

- Xiaoming Wang, Richard H. Tedford, Mauricio Antón, Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History, New York : Columbia University Press, 2008; ISBN 978-0-231-13528-3

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||