Borel–Weil–Bott theorem

In mathematics, the Borel–Weil–Bott theorem is a basic result in the representation theory of Lie groups, showing how a family of representations can be obtained from holomorphic sections of certain complex vector bundles, and, more generally, from higher sheaf cohomology groups associated to such bundles. It is built on the earlier Borel–Weil theorem of Armand Borel and André Weil, dealing just with the space of sections (the zeroth cohomology group), the extension to higher cohomology groups being provided by Raoul Bott. One can equivalently, through Serre's GAGA, view this as a result in complex algebraic geometry in the Zariski topology.

Formulation

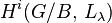

Let G be a semisimple Lie group or algebraic group over  , and fix a maximal torus T along with a Borel subgroup B which contains T. Let λ be an integral weight of T; λ defines in a natural way a one-dimensional representation Cλ of B, by pulling back the representation on T = B/U, where U is the unipotent radical of B. Since we can think of the projection map G → G/B as a principal B-bundle, for each Cλ we get an associated fiber bundle L−λ on G/B (note the sign), which is obviously a line bundle. Identifying Lλ with its sheaf of holomorphic sections, we consider the sheaf cohomology groups

, and fix a maximal torus T along with a Borel subgroup B which contains T. Let λ be an integral weight of T; λ defines in a natural way a one-dimensional representation Cλ of B, by pulling back the representation on T = B/U, where U is the unipotent radical of B. Since we can think of the projection map G → G/B as a principal B-bundle, for each Cλ we get an associated fiber bundle L−λ on G/B (note the sign), which is obviously a line bundle. Identifying Lλ with its sheaf of holomorphic sections, we consider the sheaf cohomology groups  . Since G acts on the total space of the bundle

. Since G acts on the total space of the bundle  by bundle automorphisms, this action naturally gives a G-module structure on these groups; and the Borel–Weil–Bott theorem gives an explicit description of these groups as G-modules.

by bundle automorphisms, this action naturally gives a G-module structure on these groups; and the Borel–Weil–Bott theorem gives an explicit description of these groups as G-modules.

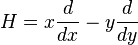

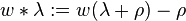

We first need to describe the Weyl group action centered at ρ. For any integral weight λ and w in the Weyl group W, we set  , where ρ denotes the half-sum of positive roots of G. It is straightforward to check that this defines a group action, although this action is not linear, unlike the usual Weyl group action. Also, a weight μ is said to be dominant if

, where ρ denotes the half-sum of positive roots of G. It is straightforward to check that this defines a group action, although this action is not linear, unlike the usual Weyl group action. Also, a weight μ is said to be dominant if  for all simple roots α. Let ℓ denote the length function on W.

for all simple roots α. Let ℓ denote the length function on W.

Given an integral weight λ, one of two cases occur:

- There is no

such that

such that  is dominant, equivalently, there exists a nonidentity

is dominant, equivalently, there exists a nonidentity  such that

such that  ; or

; or - There is a unique

such that

such that  is dominant.

is dominant.

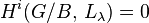

The theorem states that in the first case, we have

for all i;

for all i;

and in the second case, we have

for all

for all  , while

, while

is the dual of the irreducible highest-weight representation of G with highest weight

is the dual of the irreducible highest-weight representation of G with highest weight  .

.

It is worth noting that case (1) above occurs if and only if  for some positive root β. Also, we obtain the classical Borel–Weil theorem as a special case of this theorem by taking λ to be dominant and w to be the identity element

for some positive root β. Also, we obtain the classical Borel–Weil theorem as a special case of this theorem by taking λ to be dominant and w to be the identity element  .

.

Example

For example, consider G = SL2(C), for which G/B is the Riemann sphere, an integral weight is specified simply by an integer n, and ρ = 1. The line bundle Ln is  , whose sections are the homogeneous polynomials of degree n (i.e. the binary forms). As a representation of G, the sections can be written as Symn(C2)*, and is canonically isomorphic to Symn(C2). This gives us at a stroke the representation theory of

, whose sections are the homogeneous polynomials of degree n (i.e. the binary forms). As a representation of G, the sections can be written as Symn(C2)*, and is canonically isomorphic to Symn(C2). This gives us at a stroke the representation theory of  :

:  is the standard representation, and

is the standard representation, and  is its nth symmetric power. We even have a unified description of the action of the Lie algebra, derived from its realization as vector fields on the Riemann sphere: if H, X, Y are the standard generators of

is its nth symmetric power. We even have a unified description of the action of the Lie algebra, derived from its realization as vector fields on the Riemann sphere: if H, X, Y are the standard generators of  , then we can write

, then we can write

Positive characteristic

One also has a weaker form of this theorem in positive characteristic. Namely, let G be a semisimple algebraic group over an algebraically closed field of characteristic  . Then it remains true that

. Then it remains true that  for all i if λ is a weight such that

for all i if λ is a weight such that  is non-dominant for all

is non-dominant for all  as long as λ is "close to zero".[1] This is known as the Kempf vanishing theorem. However, the other statements of the theorem do not remain valid in this setting.

as long as λ is "close to zero".[1] This is known as the Kempf vanishing theorem. However, the other statements of the theorem do not remain valid in this setting.

More explicitly, let λ be a dominant integral weight; then it is still true that  for all

for all  , but it is no longer true that this G-module is simple in general, although it does contain the unique highest weight module of highest weight λ as a G-submodule. If λ is an arbitrary integral weight, it is in fact a large unsolved problem in representation theory to describe the cohomology modules

, but it is no longer true that this G-module is simple in general, although it does contain the unique highest weight module of highest weight λ as a G-submodule. If λ is an arbitrary integral weight, it is in fact a large unsolved problem in representation theory to describe the cohomology modules  in general. Unlike over

in general. Unlike over  , Mumford gave an example showing that it need not be the case for a fixed λ that these modules are all zero except in a single degree i.

, Mumford gave an example showing that it need not be the case for a fixed λ that these modules are all zero except in a single degree i.

Notes

- ↑ Jantzen, Jens Carsten (2003). Representations of algebraic groups (second ed.). American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-3527-0.

References

- Fulton, William; Harris, Joe (1991), Representation theory. A first course, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Readings in Mathematics 129, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-97495-8, MR 1153249, ISBN 978-0-387-97527-6.

- Baston, Robert J.; Eastwood, Michael G. (1989), The Penrose Transform: its Interaction with Representation Theory, Oxford University Press.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Bott–Borel–Weil theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- A Proof of the Borel–Weil–Bott Theorem, by Jacob Lurie. Retrieved on Jul. 13, 2014.

Further reading

- Teleman, Borel-Weil-Bott theory on the moduli stack of G-bundles over a curve

This article incorporates material from Borel–Bott–Weil theorem on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.