Boolean network

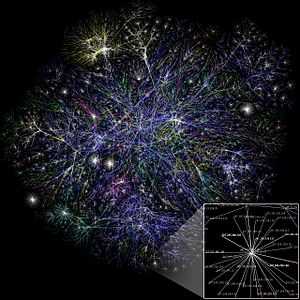

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

|

||||

A Boolean network consists of a discrete set of Boolean variables each of which has a boolean function (possibly different for each variable) assigned to it which takes inputs from a subset of those variables and output that determines the state of the variable it is assigned to. This set of functions in effect determines a topology (connectivity) on the set of variables, which then become nodes in a network. Usually, the dynamics of the system is taken as a discrete time series where the state of the entire network at time t+1 is determined by evaluating each variable's function on the state of the network at time t. This may be done synchronously or asynchronously.

Although Boolean networks are a crude simplification of genetic reality where genes are not simple binary switches, there are several cases where they correctly capture the correct pattern of expressed and suppressed genes.[1][2] The seemingly mathematical easy (synchronous) model was only fully understood in the mid 2000's.[3]

Classical model

A Boolean network is a particular kind of sequential dynamical system, where time and states are discrete, i.e. both the set of variables and the set of states in the time series each have a bijection onto an integer series. Boolean networks are related to cellular automata. Usually, cellular automata are defined with an homogeneous topology, i.e. a single line of nodes, a square or hexagonal grid of nodes or an even higher-dimensional structure, but each variable (node in the grid) may take on more than two values (and hence not be boolean).

A random Boolean network (RBN) is one that is randomly selected from the set of all possible boolean networks of a particular size, N. One then can study statistically, how the expected properties of such networks depend on various statistical properties of the ensemble of all possible networks. For example, one may study how the RBN behavior changes as the average connectivity is changed.

The first Boolean networks were proposed by Stuart A. Kauffman in 1969, as random models of genetic regulatory networks.[4]

Random Boolean networks (RBNs) are known as NK networks or Kauffman networks (Dubrova 2005). An RBN is a system of N binary-state nodes (representing genes) with K inputs to each node representing regulatory mechanisms. The two states (on/off) represent respectively, the status of a gene being active or inactive. The variable K is typically held constant, but it can also be varied across all genes. In the simplest case each gene is assigned, at random, K regulatory inputs from among the N genes, and one of the possible Boolean functions of K inputs. This gives a single random sample from the ensemble of possible networks of size N and either connectivity =k or with connectivities with some deviation around k. The state of a network at any point in time is given by the current states of all N genes. Thus the size of the state space of any such network is 2N.

Simulation of RBNs is done in discrete time steps. The state of a node at time t+1 is computed by applying the boolean function associated with the node to the state of its input nodes at time t. The sequence of states of the whole network starting from some initial state is called the trajectory of that state.

The behavior of specific RBNs and generalized classes of them has been the subject of much of Kauffman's (and others) research.

Attractors

Since a Boolean network has only 2N possible states, a trajectory will sooner or later reach a previously visited state, and thus, since the dynamics are deterministic, the trajectory will fall into a cycle. In the literature in this field, each cycle is also called an attractor (though in the broader field of dynamical systems a cycle is only an attractor if perturbations from it lead back to it). If the attractor has only a single state it is called a point attractor, and if the attractor consists of more than one state it is called a cycle attractor. The set of states that lead to an attractor is called the basin of the attractor. States which occur only at the beginning of trajectories (no trajectories lead to them), are called garden-of-Eden states and the dynamics of the network flow from these states towards attractors. The time it takes to reach an attractor is called transient time. (Gershenson 2004)

With growing computer power and increasing understanding of the seemingly simple model, different authors gave different estimates for the mean number and length of the attractors, here a brief summary of key publications.[5]

| Author | Year | Mean attractor length | Mean attractor number | comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kauffmann [4] | 1969 |  |

|

|

| Bastolla/ Parisi[6] | 1998 | faster than a power law,  |

faster than a power law,  |

first numerical evidences |

| Bilke/ Sjunnesson[7] | 2002 | linear with system size,  |

||

| Socolar/Kauffman[8] | 2003 | faster than linear,  with with  |

||

| Samuelsson/Troein[9] | 2003 | superpolynomial growth,  |

mathematical proof | |

| Mihaljev/Drossel[10] | 2005 | faster than a power law,  |

faster than a power law,  |

Topologies

- homogeneous

- normal

- scale-free (Aldana, 2003)

Updating Schemes

Classical RBNs (CRBNs) use a synchronous updating scheme and a criticism of CRBNs as models of genetic regulatory networks is that genes do not change their states all at the same moment. Harvey and Bossomaier introduced this criticism and defined asynchronous RBNs (ARBNs) where a random node is selected at each time step and updated (Harvey and Bossomaier, 1997). Since a random node is updated ARBNs are non-deterministic and do not have the cycle attractors found in CRBNs (Gershenson, 2004).

Deterministic asynchronous RBNs (DARBNs) were introduced by Gershenson as a way to have RBNs that do not have asynchronous updating but still are deterministic. In DARBNs each node has two randomly generated parameters Pi and Qi (Pi, Qi ∈ ℕ, Pi > Qi). These parameters remain fixed. A node i will be updated when t ≡ Qi (mod Pi) where t is the time step. If more than one node is to be updated at a time step the nodes are updated in a pre-defined order, e.g. from lowest to highest i. Another way to do this is to synchronously update all nodes that fulfill the updating condition. The latter scheme is called deterministic semi-synchronous or deterministic generalized asynchronous RBNs (DGARBNs) (Gershenson, 2004).

RBNs where one or more nodes are selected for updating at each time step and the selected nodes are then synchronously updated are called generalized asynchronous RBNs (GARBNs). GARBNs are semi-synchronous, but non-deterministic (Gershenson, 2002).

See also

External links

- DDLab

- Discrete Visualizer of Dynamics

- RBNLab

- NetBuilder Boolean Networks Simulator

- Open Source Boolean Network Simulator

- JavaScript Kauffman Network

- Probabilistic Boolean Networks (PBN)

- A BDD-based tool for computing attractors in Boolean Networks

- A SAT-based tool for computing attractors in Boolean Networks

References

- ↑ Albert, Réka; Othmer, Hans G (July 2003). "The topology of the regulatory interactions predicts the expression pattern of the segment polarity genes in Drosophila melanogaster". Journal of Theoretical Biology 223 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(03)00035-3.

- ↑ Li, J.; Bench, A. J.; Vassiliou, G. S.; Fourouclas, N.; Ferguson-Smith, A. C.; Green, A. R. "Imprinting of the human L3MBTL gene, a polycomb family member located in a region of chromosome 20 deleted in human myeloid malignancies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesedate=30 April 2004 101 (19): 7341–7346. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308195101. PMC 409920. PMID 15123827. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ Drossel, Barbara (December 2009). Schuster, Heinz Georg, ed. "Chapter 3. Random Boolean Networks". Reviews of Nonlinear Dynamics and Complexity. Reviews of Nonlinear Dynamics and Complexity (Wiley): 69–110. doi:10.1002/9783527626359.ch3. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kauffman, Stuart (11 October 1969). "Homeostasis and Differentiation in Random Genetic Control Networks". Nature 224 (5215): 177–178. doi:10.1038/224177a0.

- ↑ Greil, Florian (2012). "Boolean Networks as Modeling Framework". Frontiers in Plant Science 3. doi:10.3389/fpls.2012.00178.

- ↑ Bastolla, U.; Parisi, G. (May 1998). "The modular structure of Kauffman networks". Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 115 (3-4): 219–233. doi:10.1016/S0167-2789(97)00242-X.

- ↑ Bilke, Sven; Sjunnesson, Fredrik (December 2001). "Stability of the Kauffman model". Physical Review E 65 (1). doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.65.016129.

- ↑ Socolar, J.; Kauffman, S. (February 2003). "Scaling in Ordered and Critical Random Boolean Networks". Physical Review Letters 90 (6). Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90f8702S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.068702. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ Samuelsson, Björn; Troein, Carl (March 2003). "Superpolynomial Growth in the Number of Attractors in Kauffman Networks". Physical Review Letters 90 (9). Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90i8701S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.098701.

- ↑ Mihaljev, Tamara; Drossel, Barbara (October 2006). "Scaling in a general class of critical random Boolean networks". Physical Review E 74 (4). doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.74.046101.

- Aldana, M (2003). "Boolean dynamics of networks with scale-free topology" (PDF). Physica D 185: 45–66. doi:10.1016/s0167-2789(03)00174-x.

- Aldana, M., Coppersmith, S., and Kadanoff, L. P. (2003). Boolean dynamics with random couplings. In Kaplan, E., Marsden, J. E., and Sreenivasan, K. R., editors, Perspectives and Problems in Nonlinear Science. A Celebratory Volume in Honor of Lawrence Sirovich. Springer Applied Mathematical Sciences Series.

- Dubrova, E., Teslenko, M., Martinelli, A., (2005). *Kauffman Networks: Analysis and Applications, in "Proceedings of International Conference on Computer-Aided Design", pages 479-484.

- Kauffman, S. A. (1969). "Metabolic stability and epigenesis in randomly constructed genetic nets". Journal of Theoretical Biology 22: 437–467. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(69)90015-0. PMID 5803332.

- Kauffman, S. A. (1993). Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution. Oxford University Press. Technical monograph. ISBN 0-19-507951-5

- Gershenson, C. (2002). *Classification of random Boolean networks. In Standish, R. K., Bedau, M. A., and Abbass, H. A., editors, Artificial Life VIII:Proceedings of the Eight International Conference on Artificial Life, pages 1–8. MIT Press.

- Gershenson, C (2004). *Introduction to Random Boolean Networks Carlos Gershenson, editors M. Bedau and P. Husbands and T. Hutton and S. Kumar and H. Suzuki, "Workshop and Tutorial Proceedings, Ninth International Conference on the Simulation and Synthesis of Living Systems {(ALife} {IX)}", pages 160–173.

- Harvey, I. and Bossomaier, T. (1997). Time out of joint: Attractors in asynchronous random Boolean networks. In Husbands, P. and Harvey, I., editors, Proceedings of the Fourth European Conference on Artificial Life (ECAL97), pages 67–75. MIT Press.

- Wuensche, A. (1998). *Discrete dynamical networks and their attractor basins. In Standish, R., Henry, B., Watt, S., Marks, R., Stocker, R., Green, D., Keen, S., and Bossomaier, T., editors, Complex Systems'98, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.