Bone sialoprotein

| Integrin-binding sialoprotein | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

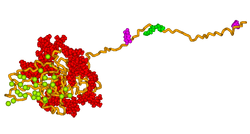

Model of human bone sialoprotein. The protein backbone is shown in orange; most of the protein is in the form of a random globule, with a surface layer of glycans (shown in red). The globule is thought to nucleate crystallization of hydroxyapatite, which is the mineral part of bone. A negatively charged region of the globule attracts calcium ions (shown as green spheres), beginning the crystallization process. The unwound protein strand on the right of the picture is thought to anchor the protein to the cell surface, before it is transferred to the collagen fibrils that provide the main organic component of bone[1]. | |||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||

| Symbols | IBSP ; BNSP; BSP; BSP-II; SP-II | ||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 147563 MGI: 96389 HomoloGene: 3644 GeneCards: IBSP Gene | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Orthologs | |||||||||||||

| Species | Human | Mouse | |||||||||||

| Entrez | 3381 | 15891 | |||||||||||

| Ensembl | ENSG00000029559 | ENSMUSG00000029306 | |||||||||||

| UniProt | P21815 | Q61711 | |||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | NM_004967 | NM_008318 | |||||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | NP_004958 | NP_032344 | |||||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 4: 88.72 – 88.73 Mb | Chr 5: 104.3 – 104.31 Mb | |||||||||||

| PubMed search | |||||||||||||

Bone sialoprotein (BSP) is a component of mineralized tissues such as bone, dentin, cementum and calcified cartilage. BSP is a significant component of the bone extracellular matrix and has been suggested to constitute approximately 8% of all non-collagenous proteins found in bone and cementum.[2] BSP, a SIBLING protein, was originally isolated from bovine cortical bone as a 23-kDa glycopeptide with high sialic acid content.[3][4]

The human variant of BSP is called bone sialoprotein 2 also known as cell-binding sialoprotein or integrin-binding sialoprotein and is encoded by the IBSP gene.[5]

Structure

Native BSP has an apparent molecular weight of 60-80 kDa based on SDS-PAGE, which is a considerable deviation from the predicted weight (based on cDNA sequence) of approximately 33 kDa.[6] The mammalian BSP cDNAs encode for proteins averaging 327 amino acids, which includes the 16-residue preprotein secretory signal peptide. Among the mammalian cDNAs currently characterized, there is an approximate 45% conservation of sequence identity and a further 10-23% conservative substitution. The protein is highly acidic (pKa of ~ 3.9)[7] and contains a large amount of Glu residues, constituting ~22% of the total amino acid.

Secondary structure prediction and hydrophobicity analyses suggest that the primary sequence of BSP has an open, flexible structure with the potential to form regions of α-helix and some β-sheet.[8] However, the majority of studies have demonstrated that BSP has no α-helical or β-sheet structure by 1D NMR[7][9] and circular dichroism.[10] Analysis of native protein by electron microscopy confirm that the protein has an extended structure approximately 40 nm in length.[11] This flexible conformation suggests that the protein has few structural domains, however it has been suggested that there may be several spatially segmented functional domains including a hydrophobic collagen-binding domain (rattus norvegicus residues 36-57),[12] a hydroxyapatite-nucleating region of contiguous glutamic acid residues (rattus norvegicus residues 78-85, 155-164)[10] and a classical integrin-binding motif (RGD) near the C-terminal (rattus norvegicus residues 288-291).

BSP has been demonstrated to be extensively post-translationally modified, with carbohydrates and other modifications comprising approximately 50% of the molecular weight of the native protein.[13][14] These modifications, which include N- and O-linked glycosylation, tyrosine sulfation and serine and threonine phosphorylation, make the protein highly heterogeneous.

Function

The amount of BSP in bone and dentin is roughly equal,[15] however the function of BSP in these mineralized tissues is not known. One possibility is that BSP acts as a nucleus for the formation of the first apatite crystals.[16] As the apatite forms along the collagen fibres within the extracellular matrix, BSP could then help direct, redirect or inhibit the crystal growth.

Additional roles of BSP are MMP-2 activation, angiogenesis, and protection from complement-mediated cell lysis. Regulation of the BSP gene is important to bone matrix mineralization and tumor growth in bone.[17]

References

- ↑ Vincent, K.; Durrant, M.C. (2013). "A structural and functional model for human bone sialoprotein". Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 39: 108–117. doi:10.1016/j.jmgm.2012.10.007.

- ↑ Fisher LW, McBride OW, Termine JD, Young MF (February 1990). "Human bone sialoprotein. Deduced protein sequence and chromosomal localization". J. Biol. Chem. 265 (4): 2347–51. PMID 2404984.

- ↑ Williams PA, Peacocke AR (November 1965). "The physical properties of a glycoprotein from bovine cortical bone (bone sialoprotein)". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 101 (3): 327–35. doi:10.1016/0926-6534(65)90011-4. PMID 5862222.

- ↑ Herring GM (February 1964). "Comparison of bovine bone sialoprotein and serum orosomucoid". Nature 201 (4920): 709. doi:10.1038/201709a0. PMID 14139700.

- ↑ Kerr JM, Fisher LW, Termine JD, Wang MG, McBride OW, Young MF (August 1993). "The human bone sialoprotein gene (IBSP): genomic localization and characterization". Genomics 17 (2): 408–15. doi:10.1006/geno.1993.1340. PMID 8406493.

- ↑ Fisher LW, Whitson SW, Avioli LV, Termine JD (October 1983). "Matrix sialoprotein of developing bone". J. Biol. Chem. 258 (20): 12723–7. PMID 6355090.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Stubbs JT, Mintz KP, Eanes ED, Torchia DA, Fisher LW (August 1997). "Characterization of native and recombinant bone sialoprotein: delineation of the mineral-binding and cell adhesion domains and structural analysis of the RGD domain". J. Bone Miner. Res. 12 (8): 1210–22. doi:10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.8.1210. PMID 9258751.

- ↑ Shapiro HS, Chen J, Wrana JL, Zhang Q, Blum M, Sodek J (November 1993). "Characterization of porcine bone sialoprotein: primary structure and cellular expression". Matrix 13 (6): 431–40. doi:10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80109-5. PMID 8309422.

- ↑ Fisher LW, Torchia DA, Fohr B, Young MF, Fedarko NS (January 2001). "Flexible structures of SIBLING proteins, bone sialoprotein, and osteopontin". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280 (2): 460–5. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.4146. PMID 11162539.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Tye CE, Rattray KR, Warner KJ, Gordon JA, Sodek J, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA (March 2003). "Delineation of the hydroxyapatite-nucleating domains of bone sialoprotein". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (10): 7949–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M211915200. PMID 12493752.

- ↑ Oldberg A, Franzén A, Heinegård D (December 1988). "The primary structure of a cell-binding bone sialoprotein". J. Biol. Chem. 263 (36): 19430–2. PMID 3198635.

- ↑ Tye CE, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA (April 2005). "Identification of the type I collagen-binding domain of bone sialoprotein and characterization of the mechanism of interaction". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (14): 13487–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408923200. PMID 15703183.

- ↑ Kinne RW, Fisher LW (July 1987). "Keratan sulfate proteoglycan in rabbit compact bone is bone sialoprotein II". J. Biol. Chem. 262 (21): 10206–11. PMID 2956253.

- ↑ Ganss B, Kim RH, Sodek J (1999). "Bone sialoprotein". Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 10 (1): 79–98. doi:10.1177/10454411990100010401. PMID 10759428.

- ↑ Qin C, Brunn JC, Jones J, George A, Ramachandran A, Gorski JP, Butler WT (April 2001). "A comparative study of sialic acid-rich proteins in rat bone and dentin". Eur. J. Oral Sci. 109 (2): 133–41. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0722.2001.00001.x. PMID 11347657.

- ↑ Hunter GK, Goldberg HA (August 1994). "Modulation of crystal formation by bone phosphoproteins: role of glutamic acid-rich sequences in the nucleation of hydroxyapatite by bone sialoprotein". Biochem. J. 302 ( Pt 1) (Pt 1): 175–9. PMC 1137206. PMID 7915111.

- ↑ Ogata Y (April 2008). "Bone sialoprotein and its transcriptional regulatory mechanism". J. Periodont. Res. 43 (2): 127–35. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01014.x. PMID 18302613.

Further reading

- Karadag A, Fisher LW (2006). "Bone sialoprotein enhances migration of bone marrow stromal cells through matrices by bridging MMP-2 to alpha(v)beta3-integrin". J. Bone Miner. Res. 21 (10): 1627–36. doi:10.1359/jbmr.060710. PMID 16995818.

- Barnes GL, Javed A, Waller SM et al. (2003). "Osteoblast-related transcription factors Runx2 (Cbfa1/AML3) and MSX2 mediate the expression of bone sialoprotein in human metastatic breast cancer cells". Cancer Res. 63 (10): 2631–7. PMID 12750290.

- Carlinfante G, Vassiliou D, Svensson O et al. (2003). "Differential expression of osteopontin and bone sialoprotein in bone metastasis of breast and prostate carcinoma". Clin. Exp. Metastasis 20 (5): 437–44. doi:10.1023/A:1025419708343. PMID 14524533.

- Hwang Q, Cheifetz S, Overall CM et al. (2009). "Bone sialoprotein does not interact with pro-gelatinase A (MMP-2) or mediate MMP-2 activation". BMC Cancer 9: 121. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-9-121. PMC 2679042. PMID 19386107.

- Styrkarsdottir U, Halldorsson BV, Gretarsdottir S et al. (2009). "New sequence variants associated with bone mineral density". Nat. Genet. 41 (1): 15–7. doi:10.1038/ng.284. PMID 19079262.

- Zhang L, Hou X, Lu S et al. (2010). "Predictive significance of bone sialoprotein and osteopontin for bone metastases in resected Chinese non-small-cell lung cancer patients: a large cohort retrospective study". Lung Cancer 67 (1): 114–9. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.03.017. PMID 19376608.

- Roca H, Phimphilai M, Gopalakrishnan R et al. (2005). "Cooperative interactions between RUNX2 and homeodomain protein-binding sites are critical for the osteoblast-specific expression of the bone sialoprotein gene". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (35): 30845–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M503942200. PMID 16000302.

- Lamour V, Detry C, Sanchez C et al. (2007). "Runx2- and histone deacetylase 3-mediated repression is relieved in differentiating human osteoblast cells to allow high bone sialoprotein expression". J. Biol. Chem. 282 (50): 36240–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M705833200. PMID 17956871.

- Ogata Y (2008). "Bone sialoprotein and its transcriptional regulatory mechanism". J. Periodont. Res. 43 (2): 127–35. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01014.x. PMID 18302613.

- Papotti M, Kalebic T, Volante M et al. (2006). "Bone sialoprotein is predictive of bone metastases in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective case-control study". J. Clin. Oncol. 24 (30): 4818–24. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1952. PMID 17050866.

- Frank O, Heim M, Jakob M et al. (2002). "Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis of human bone marrow stromal cells during osteogenic differentiation in vitro". J. Cell. Biochem. 85 (4): 737–46. doi:10.1002/jcb.10174. PMID 11968014.

- Yerges LM, Klei L, Cauley JA et al. (2009). "High-Density Association Study of 383 Candidate Genes for Volumetric BMD at the Femoral Neck and Lumbar Spine Among Older Men". J. Bone Miner. Res. 24 (12): 2039–49. doi:10.1359/jbmr.090524. PMC 2791518. PMID 19453261.

- Gordon JA, Sodek J, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA (2009). "Bone sialoprotein stimulates focal adhesion-related signaling pathways: role in migration and survival of breast and prostate cancer cells". J. Cell. Biochem. 107 (6): 1118–28. doi:10.1002/jcb.22211. PMID 19492334.

- Araki S, Mezawa M, Sasaki Y et al. (2009). "Parathyroid hormone regulation of the human bone sialoprotein gene transcription is mediated through two cAMP response elements". J. Cell. Biochem. 106 (4): 618–25. doi:10.1002/jcb.22039. PMID 19127545.

- Wuttke M, Müller S, Nitsche DP, Paulsson M, Hanisch FG, Maurer P (September 2001). "Structural characterization of human recombinant and bone-derived bone sialoprotein. Functional implications for cell attachment and hydroxyapatite binding". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (39): 36839–48. doi:10.1074/jbc.M105689200. PMID 11459848.

- Hilbig H, Wiener T, Armbruster FP et al. (2005). "Effects of dental implant surfaces on the expression of bone sialoprotein in cells derived from human mandibular bone". Med. Sci. Monit. 11 (4): BR111–5. PMID 15795688.

- Koller DL, Ichikawa S, Lai D et al. (2010). "Genome-Wide Association Study of Bone Mineral Density in Premenopausal European-American Women and Replication in African-American Women". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95 (4): 1802–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-1903. PMC 2853986. PMID 20164292.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH et al. (2002). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Fujisawa R (2002). "[Recent advances in research on bone matrix proteins]". Nippon Rinsho. 60 Suppl 3: 72–8. PMID 11979972.

- Loibl S, Königs A, Kaufmann M, Costa SD, Bischoff J (December 2006). "[PTHrP and bone sialoprotein as prognostic markers for developing bone metastases in breast cancer patients]". Zentralbl Gynakol (in German) 128 (6): 330–5. doi:10.1055/s-2006-942314. PMID 17213971.

- Uccello M, Malaguarnera G, Vacante M et al. (2011). "Serum bone sialoprotein levels and bone metastases". J. Cancer. Res. Ther. 7 (2): 115–9. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.82912. PMID 21768695.