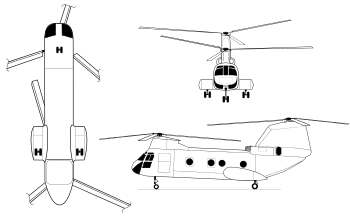

Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight

| CH-46 Sea Knight | |

|---|---|

| |

| A U.S. Marine Corps CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter flies over Huntington Beach, California in October 2011. | |

| Role | Cargo helicopter |

| Manufacturer | Vertol Aircraft Corp. Boeing Vertol |

| First flight | August 1962 |

| Introduction | 1964 |

| Retired | 2004 (U.S. Navy) 2015 (USMC) |

| Status | In limited service |

| Primary users | United States Marine Corps (historical) United States State Department Swedish Air Force (historical) Japan (historical) |

| Produced | 1962–1971 |

| Number built | H-46: 524[1] |

|

| |

The Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight is a medium-lift tandem rotor transport helicopter powered by twin turboshaft aircraft engines. It was used by the United States Marine Corps (USMC) to provide all-weather, day-or-night assault transport of combat troops, supplies and equipment until its replacement by the MV-22 Osprey. Additional tasks include combat support, search and rescue (SAR), support for forward refueling and rearming points, CASEVAC and Tactical Recovery of Aircraft and Personnel (TRAP).

The Sea Knight was also the U.S. Navy's standard medium-lift utility helicopter until it was phased out in favor of the MH-60S Knighthawk in the early 2000s. Canada also operated the Sea Knight, designated as CH-113, and operated them in the SAR role until 2004. Other export customers include Japan, Sweden, and Saudi Arabia. The commercial version is the BV 107-II, commonly referred to simply as the "Vertol".

Development

Origins

Piasecki Helicopter was a pioneering developer of tandem-rotor helicopters, with the most famous previous helicopter being the H-21 "Flying Banana". Piasecki Helicopter became Vertol in 1955 and work began on a new tandem rotor helicopter designated the Vertol Model 107 or V-107 in 1956. The V-107 prototype had two Lycoming T53 turboshaft engines, producing 877 shp (640 kW) each.[2] The first flight of the V-107 took place on 22 April 1958.[3] The V-107 was then put through a flight demonstration tour in the United States and overseas. In June 1958, the U.S. Army awarded a contract to Vertol for ten production aircraft designated "YHC-1A".[4]

The order was later decreased to three, so that the Army could divert funds for the V-114, also a turbine powered tandem, but larger than the V-107.[4] The Army's three YHC-1As were powered by GE-T-58 engines. The YHC-1As first flew in August 1959, and were followed by an improved commercial/export model, the 107-II.[1] During 1960, the U.S. Marine Corps evolved a requirement for a medium-lift, twin-turbine troop/cargo assault helicopter to replace the piston-engined types then in use.[5] That same year Boeing acquired Vertol and renamed the group Boeing Vertol.[4] Following a competition, Boeing Vertol was selected to build its model 107M as the HRB-1, early in 1961.[1] In 1962 the U.S. Air Force ordered 12 XCH-46B Sea Knights with the XH-49A designation, but later cancelled the order due to a delivery delay and opted for the Sikorsky S-61R instead.[6]

Following the Sea Knight's first flight in August 1962, the designation was changed to CH-46A. In November 1964, introduction of the Marines' CH-46A and the Navy's UH-46As began. The UH-46A variant was modified for the vertical replenishment role.[1] The CH-46A was equipped with a pair of T58-GE8-8B turboshaft engines rated at 1,250 shp (930 kW) each and could carry 17 passengers or 4,000 pounds (1,815 kg) of cargo.[7]

Further developments

Production of the improved CH-46D followed with deliveries beginning in 1966. Its improvements included modified rotor blades and more powerful T58-GE-10 turboshaft engines[1] rated at 1,400 shp (1,040 kW) each. The increased power allowed the D-model to carry 25 troop or 7,000 pounds (3,180 kg) of cargo.[7] The CH-46D was introduced to the Vietnam theater in late 1967, supplementing the U.S. Marine Corps' existing unreliable and problematic CH-46A fleet.[8] Along with the USMC's CH-46Ds, the U.S. Navy received a small number of UH-46Ds for ship resupply.[9] Also, approximately 33 CH-46As were upgraded to CH-46Ds.[7]

The Marines also received CH-46Fs from 1968 to 1971. The F-model retained the D-model's T58-GE-10 engines but revised the avionics and included other modifications. The CH-46F was the final production model.[1] The Sea Knight has undergone upgrades and modifications. Most of the U.S. Marine Corps' Sea Knights were upgraded to CH-46E standard. The CH-46E features fiberglass rotor blades, airframe reinforcement, and further uprated T58-GE-16 engines producing 1,870 shp (1,390 kW) each. Some CH-46Es have been given double fuel capacity.[7] The Dynamic Component Upgrade (DCU), incorporated starting in the mid-1990s, provides for increased capability through strengthened drive systems and rotor controls.

The commercial variant, the BV 107-II, was first ordered by New York Airways in 1960. They took delivery of their first three aircraft, configured for 25 passengers, in July 1962.[5] In 1965, Boeing Vertol sold the manufacturing rights of the 107 to Kawasaki Heavy Industries. Under this arrangement, all Model 107 civilian and military aircraft built in Japan are known as KV 107.[5] On 15 December 2006, Columbia Helicopters, Inc acquired the type certificate for the Boeing Vertol 107-II, and is in the process of acquiring a Production Certificate from the FAA. Plans for actual production of the aircraft have not been announced.[5]

Design

The CH-46 has tandem counter-rotating rotors powered by two GE T58 turboshaft engines. The engines are mounted on each side of the rear rotor pedestal with a driveshaft to the forward rotor. The engines are coupled so either could power both rotors in an emergency. The rotors feature three blades and can be folded for on-ship operations.[7] The CH-46 has fixed tricycle landing gear, with twin wheels on all three units. The gear configuration causes a nose-up stance to facilitate cargo loading and unloading. The main gear are fitted in rear sponsons that also contain fuel tanks with a total capacity of 350 US gallons (1,438 L).[7]

The CH-46 has a cargo bay with a rear loading ramp that could be removed or left open in flight for extended cargo or for parachute drops. An internal winch is mounted in the forward cabin and can be used to pull external cargo on pallets into the aircraft via the ramp and rollers. A belly sling hook (cargo hook) which is usually rated at 10,000 lb (4,500 kg). could be attached for carrying external cargo. Although the hook is rated at 10,000 lb (4,500 kg)., the limited power produced by the engines precludes the lifting of such weight. It usually has a crew of three, but can accommodate a larger crew depending on mission specifics. For example, a Search and Rescue variant will usually carry a crew of five (Pilot, Co-Pilot, Crew Chief, Swimmer, and Medic) to facilitate all aspects of such a mission. A pintle-mounted 0.50 in (12.7 mm) Browning machine gun is mounted on each side of the helicopter for self-defense.[7] Service in southeast Asia resulted in the addition of armor with the guns.[1]

Operational history

United States

Known colloquially as the "Phrog", the Sea Knight was used in all U.S. Marine operational environments between its introduction during the Vietnam War and its frontline retirement in 2014.[11] The type's longevity and reputation for reliability led to mantras such as "phrogs phorever" and "never trust a helicopter under 30".[12] CH-46s transported personnel, evacuated wounded, supplied forward arming and refueling points (FARP), performed vertical replenishment, search and rescue, recovered downed aircraft and crews and other tasks.

During the Vietnam War, the CH-46 was one of the prime US troop transport helicopters in the theatre, slotting between the smaller Bell UH-1 Iroquois and larger Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion. During the 1972 Easter Offensive, Sea Knights saw heavy use to convey US and South Vietnamese ground forces to and around the front lines.[13] CH-47 operations were plagued by major technical problems; the engines, being prone to foreign object damage (FOD) from debris being ingested when hovering close to the ground and subsequently suffering a compressor stall, had a lifespan as low as 85 flight hours; on 21 July 1966, all CH47s were grounded until more efficient filters had been fitted.[14] By the end of US military operations in Vietnam, over a hundred Sea Knights had been lost to enemy fire.[15]

In February 1968 the Marine Corps Development and Education Command obtained several CH-46 units to perform herbicide dissemination tests using HIDAL (Helicopter, Insecticide Dispersal Apparatus, Liquid) systems; testing indicated the need for redesign and further study.[16] Tandem-rotor helicopters were often used to transport nuclear warheads; the CH-46A was evaluated to deploy Naval Special Forces with the Special Atomic Demolition Munition (SADM).[17] Nuclear Weapon Accident Exercise 1983 (NUWAX-83), simulating the crash of a Navy CH-46E carrying 3 nuclear warheads, was conducted at the Nevada Test Site on behalf of several federal agencies; the exercise, which used real radiological agents, was depicted in a Defense Nuclear Agency-produced documentary.[18]

CH-46E Sea Knights were also used by the U.S. Marine Corps during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In one incident on 1 April 2003, Marine CH-46Es and CH-53Es carried U.S. Army Rangers and Special Operations troops on an extraction mission for captured Army Private Jessica Lynch from an Iraqi hospital.[19] During the subsequent occupation of Iraq and counter-insurgency operations, the CH-46E was heavily used in the CASEVAC role, being required to maintain 24/7 availability regardless of conditions.[20] According to authors Williamson Murray and Robert H Scales, the Sea Knight displayed serious reliability and maintenance problems during its deployment to Iraq, as well as "limited lift capabilities".[21] Following the loss of numerous US helicopters in the Iraqi theatre, the Marines opted to equip their CH-46s with more advanced anti-missile countermeasures.[22]

The U.S. Navy retired the type on 24 September 2004, replacing it with the MH-60S Seahawk;[23] the Marine Corps maintained its fleet as the MV-22 Osprey was fielded.[24] In March 2006 Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 263 (HMM-263) was deactivated and redesignated VMM-263 to serve as the first MV-22 squadron.[25] The replacement process continued through the other medium helicopter squadrons into 2014. On 5 October 2014, the Sea Knight performed its final service flight with the U.S. Marine Corps at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar. HMM-364 was the last squadron to use it outside the United States, landing it aboard the USS America (LHA-6) on her maiden transit. On 9 April 2015, the CH-46 was retired by the Marine Medium Helicopter Training Squadron 164, the last Marine Corps squadron to transition to the MV-22.[26][27]

Canada

The Royal Canadian Air Force procured six CH-113 Labrador helicopters for the SAR role and the Canadian Army acquired 12 of the similar CH-113A Voyageur for the medium-lift transport role. The RCAF Labradors were delivered first with the first one entering service on 11 October 1963.[28][29] When the larger CH-147 Chinook was procured by the Canadian Forces in the mid-1970s, the Voyageur fleet was converted to Labrador specifications to undertake SAR missions. The refurbished Voyageurs were re-designated as CH-113A Labradors, thus a total of 15 Labradors were ultimately in service.[29]

The Labrador was fitted with a watertight hull for marine landings, a 5,000 kilogram cargo hook and an external rescue hoist mounted over the right front door. It featured a 1,110 kilometer flying range, emergency medical equipment and an 18-person passenger capacity. By the 1990s, heavy use and hostile weather conditions had taken their toll on the Labrador fleet, resulting in increasing maintenance costs and the need for prompt replacement.[29] In 1981, a mid-life upgrade of the fleet was carried out by Boeing Canada in Arnprior, Ontario. Known as the SAR-CUP (Search and Rescue Capability Upgrade Program), the refit scheme included new instrumentation, a nose-mounted weather radar, a tail-mounted auxiliary power unit, a new high-speed rescue hoist mounted over the side door and front-mounted searchlights. A total of six CH-113s and five CH-113As were upgraded with the last delivered in 1984.[29]

In 1992, it was announced that the Labradors were to be replaced by 15 new helicopters, a variant of the AgustaWestland EH101, designated CH-149 Chimo. The order was subsequently cancelled by the Jean Chrétien Liberal government in 1993, resulting in cancellation penalties, as well as extending the service life of the Labrador fleet. However, in 1998, a CH-113 from CFB Greenwood crashed on Quebec's Gaspé Peninsula while returning from a SAR mission, resulting in the deaths of all crewmembers on board. The crash placed pressure upon the government to procure a replacement, thus an order was placed with the manufacturers of the EH101 for 15 aircraft to perform the search-and-rescue mission, designated CH-149 Cormorant. CH-149 deliveries began in 2003, allowing the last CH-113 to be retired in 2004.[29] In October 2005 Columbia Helicopters of Aurora, Oregon purchased eight of the retired CH-113 Labradors to add to their fleet of 15 Vertol 107-II helicopters.[30]

Sweden

In 1963, Sweden procured ten UH-46B from the US as a transport and anti-submarine helicopter for the Swedish armed forces, designated Hkp 4A. In 1973, a further eight Kawasaki-built KV-107, which were accordingly designated Hkp 4B, were acquired to replace the older Piasecki H-21. During the Cold War, the fleet's primary missions were anti-submarine warfare and troop transportation, they were also frequently employed in the search and rescue role. In the 1980s, the Hkp 4A was phased out, having been replaced by the Eurocopter AS332 Super Puma; the later Kawasaki-built Sea Knights continued in operational service until 2011, they were replaced by the UH-60 Black Hawk.

Civilian

The civilian version, designated as the BV 107-II Vertol,[31] was developed prior to the military CH-46. It was operated commercially by New York Airways, Pan American World Airways and later on by Columbia Helicopters.[31] Among the diversity of tasks was pulling a hover barge.[32][33] In December 2006, Columbia Helicopters purchased the type certificate of the Model 107 from Boeing, with the aim of eventually producing new-build aircraft themselves.[34]

Variants

American versions

%2C_1968%2C_vertrep.jpg)

- Model 107

- Company model number for basic prototype, one built.[35]

- Model 107-II

- Commercial airline helicopter. All subsequent commercial aircraft were produced as BV 107-II-2, two built as Boeing Vertol prototypes, five sold to New York Airways, ten supplied to Kawasaki as sub-assemblies or as parts.[36]

- Model 107M

- Company model number for military transport of BV-107/II-2 for the U.S. Marine Corps.[37]

- YHC-1A

- Vertol Model 107 for test and evaluation by the United States Army. Adopted by the U.S. Marine Corps as the HRB-1. Later redesignated YCH-46C, three built.

- HRB-1

- Original designation before being renamed as CH-46A before delivery under the 1962 United States Tri-Service aircraft designation system.

- CH-46A

- Medium-lift assault and cargo transport and SAR helicopter for the USMC, fitted with two 1,250 shp (935 kW) General Electric T58-GE-8 turboshaft engines. Previously designated HRB-1. 160 built for USMC, one static airframe.

- UH-46A

- Medium-lift utility transport helicopter for the United States Navy. Similar to the CH-46A. 14 built.

- HH-46A

- Approximately 50 CH-46As were converted into SAR helicopters for the United States Navy base rescue role.

- RH-46A

- Planned conversion of CH-46As into minesweeping helicopters for the US Navy, none converted. Nine SH-3As were converted to the RH-3A configuration instead.

- UH-46B

- Development of the CH-46A to specification HX/H2 for the United States Air Force; 12 ordered in 1962, cancelled and Sikorsky S-61R / CH-3C ordered instead.

- YCH-46C

- YHC-1A redesignated in 1962. United States Army retained two, NASA used one for vertical autonomous landing trials (VALT).

- CH-46D

- Medium-lift assault and cargo transport helicopter for the USMC, fitted with two 1,400 shp (1,044 kW) General Electric T58-GE-10 turboshaft engines. 266 built.

- HH-46D

- Surviving HH-46A were upgraded and a small number of UH-46Ds were converted into SAR helicopters. SAR upgrades included the addition of an external rescue hoist near the front crew door and an 18-inch X 18-inch Doppler RADAR system located behind the nose landing gear, which provided for automatic, day/night, over-water hovering capability for at sea rescue. Additionally a "Loud Hailer" was installed opposite the crew entrance door for communicating with downed aviators on the ground or in the water.

- UH-46D

- Medium-lift utility transport helicopter for the US Navy combat supply role. Similar to the CH-46D. Ten built and one conversion from CH-46D.

- CH-46E

- Approximately 275 -A, -D, and -F airframes were updated to CH-46E standards with improved avionics, hydraulics, drive train and upgraded T58-GE-16 and T58-GE-16/A engines.

- HH-46E

- Three CH-46Es were converted into SAR helicopters for Marine Transport Squadron One (VMR-1) at MCAS Cherry Point.[38]

- CH-46F

- Improved version of CH-46D, electrical distribution, com/nav update BUNO 154845-157726. Last production model in the United States. 174 built, later reverted to CH-46E.

- VH-46F

- Unofficial designation of standard CH-46F used by HMX-1 as VIP support transport helicopter.

- CH-46X

- Replacement helicopter based on the Boeing Model 360, this Advance Technology Demonstrator from the 1980s never entered production. The aircraft relied heavily on composites for its construction and had a beefier drive train to handle the twin Avco-Lycoming AL5512 engines (4,200 shp).[39]

- XH-49

- Original designation of UH-46B.

Canadian versions

- CH-113 Labrador

- Search and rescue version of the Model 107-II-9 for the Royal Canadian Air Force.[40]

- CH-113A Voyageur

- Assault and utility transport version of the Model 107-II-28 for the Canadian Army. Later converted to CH-113A Labrador when the Canadian Forces acquired the CH-47 Chinook.[41]

Swedish versions

- HKP 4A

- Boeing Vertol 107-II-14, used originally by Air Force for SAR, ten built.[42]

- HKP 4B

- Boeing Vertol 107-II-15, mine-layer/ASW/SAR helicopter for Navy, three built and one conversion from Boeing-Vertol civil prototype.[43]

- HKP 4C

- Kawasaki KV-107-II-16, advanced mine-layer/ASW/SAR helicopter for Navy,eight built.

- HKP 4D

- Rebuilt HKP 4A for Navy as SAR/ASW helicopter, four conversions.[44]

Japanese versions

_lifts_cargo_during_a_vertical_replenishment_(VERTREP).jpg)

- KV-107II-1 (CT58-110-1)

- Utility transport version, one built from Boeing-supplied kits.

- KV-107II-2 (CT58-110-1)

- Commercial airline version, nine built from Boeing-supplied kits.

- KV-107IIA-2 (CT58-140-1)

- Improved version of the KV-107/II-2, three built.

- KV-107II-3 (CT58-110-1)

- Minesweeping version for the JMSDF, two built.

- KV-107IIA-3 (CT58-IHI-10-M1)

- Uprated version of the KV-107/II-3, seven built.

- KV-107II-4 (CT58-IHI-110-1)

- Assault and utility transport version for the JGSDF, 41 built.

- KV-107II-4A (CT58-IHI-110-1)

- VIP version of the KV-107/II-4, one built.

- KV-107IIA-4 (CT58-IHI-140-1)

- Uprated version of the KV-107/II-4, 18 built.

- KV-107II-5 (CT58-IHI-110-1)

- Long-range SAR version for the JASDF, 17 built.

- KV-107IIA-5 (CT58-IHI-104-1)

- Uprated version of the KV-107II-5, 35 built.

- KV-107II-7 (CT58-110-1)

- VIP transport version, one built.

- KV-107II-16

- HKP 4C for Swedish Navy. Powered by Rolls-Royce Gnome H.1200 turboshaft engines, eight built.

- KV-107IIA-17 (CT58-140-1)

- Long-range transport version for the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department, one built.

- KV-107IIA-SM-1 (CT58-IHI-140-1M1)

- Firefighting helicopter for Saudi Arabia, seven built.

- KV-107IIA-SM-2 (CT58-IHI-140-1M1)

- Aeromedical and rescue helicopter for Saudi Arabia, four built.

- KV-107IIA-SM-3 (CT58-IHI-140-1M1)

- VIP transport helicopter for Saudi Arabia, two built.

- KV-107IIA-SM-4 (CT58-IHI-140-1M1)

- Air ambulance helicopter for Saudi Arabia, three built.

Source:[45]

Operators

Military and Government operators

Civilian operators

- Helifor Canada[47]

Former operators

- Japan Air Self-Defense Force[51]

- Japan Ground Self-Defense Force[51]

- Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force[51]

- Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department[52]

- New York Airways[57]

- Pan American Airways[58]

- United States Marine Corps[59]

Notable accidents and incidents

- On 15 July 1966 during Operation Hastings, two CH-46As BuNo 151930 and BuNo 151936 of HMM-164 collided at LZ Crow while another, BuNo 151961, crashed into a tree avoiding the first two, resulting in 2 Marines killed. Another CH-46 BuNo 152500 of HMM-265 was shot down at the LZ later that day resulting in 13 Marines killed.[71]

- On 4 June 1968 CH-46D BuNo 152533 of HMM-165 was hit by anti-aircraft fire at Landing Zone Loon and crashed killing 13 Marines[72]

- On 14 March 1969 CH-46D BuNo 154841 of HMM-161 was hit by a B-40 rocket as it conducted a resupply and medevac mission at Landing Zone Sierra, killing 12 Marines and 1 Navy corpsman.[73]

- On 9 December 1999, a CH-46D Sea Knight BuNo 154790 of HMM-166 crashed during a boarding exercise off the coast of San Diego, California, killing seven U.S. Marines. The pilot landed the CH-46D short on the deck of the USNS Pecos, causing the left rear tire and strut to become entangled in the restraint equipment at the back of the ship, which caused it to plunge into the ocean.[74]

Specifications (CH-46E)

Data from Frawley,[75] Donald[3]

General characteristics

- Crew: five: two pilots, one crew chief, one aerial gunner/observer, one tail gunner

- Capacity: ** 24 troops or

- 15 stretchers and two attendants or

- 2270 kg (5,000 lb)

- Length: 44 ft 10 in fuselage (13.66 m

- Fuselage width: 7 ft 3 in (2.2 m))

- Rotor diameter: 50 ft (15.24 m)

- Height: 16 ft 9 in (5.09 m)

- Disc area: 3,927 ft² (364.8 m²)

- Empty weight: 11,585 lb (5,255 kg)

- Loaded weight: 17,396 lb (7,891 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 24,300 lb (11,000 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric T58-GE-16 turboshafts, 1,870 shp (1,400 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 166 mph (144 knots, 267 km/h)

- Range: 633 mi (550 nmi, 1,020 km)

- Ferry range: 690 mi (600 nmi, 1,110 km)

- Service ceiling: 17,000 ft (5,180 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,715 ft/min (8.71 m/s)

- Disc loading: 4.43 lb/ft² (21.6 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.215 hp/lb (354 W/kg)

Armament

- Guns: Two door-mounted GAU-15/A .50 BMG (12.7 x 99 mm) machine guns (optional), one ramp-mounted M240D 7.62 x 51 mm machine gun (optional)

Aircraft on display

- National Air Force Museum of Canada – Labrador 11315[76]

- Canada Aviation and Space Museum – Labrador 11301[29]

- Comox Air Force Museum – Labrador 11310[77]

- Japan Air Self Defense Force Hamamatsu Air Base Publication Center, Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan[78]

- Kakamigahara Aerospace Science Museum, Kakamigahara, Gifu, Japan[79]

- Kawasaki Vertol 107-II – Kawasaki Good Times World, within Kobe Maritime Museum, Kobe, Hyōgo, Japan.[80][81]

- Aeroseum, Gothenburg, Sweden – Boeing Vertol/Kawasaki KV-107-II (CH-46), Hkp 4C, c/n 4093, Fv 04072 "72"[82]

_04064_64_(8315424775).jpg)

- Swedish Air Force Museum, Linköping Sweden. Prototype BV-107-II N6679D[83] Bought used from Boeing in 1970.

- Flying Leatherneck Aviation Museum, San Diego, California, USA has CH-46E #154803 (c/n 2410) as YS-09 Lady Ace 09 of HMM-165. The CH-46 took part in Operation Frequent Wind and was used to evacuate Ambassador Graham Martin, the last United States Ambassador to South Vietnam from the United States Embassy, Saigon on 30 April 1975.[84][85]

- USS Midway Museum in San Diego, California displays HH-46A #150954 (c/n 2040) as U.S. Navy SA-46 of HC-3 on one side and VR-46 of HC-11 on the other.[86]

- National Museum of Naval Aviation in Pensacola, FL displays HH-46D #151952 (c/n 2102) as U.S Navy HW-00 of HC-6.[87]

- Carolinas Aviation Museum, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA has Raymond Clausen's Medal of Honor mission CH-46E #153389 (c/n 2287) as HMM-263 EG-16. The rear fuselage of #153335 was used in restoration.[88]

- New River Aviation Memorial at the front gate of Marine Corps Air Station New River, (part of Camp Lejeune) in Jacksonville, North Carolina- CH46E #153402 (c/n 2300) as YS-02 of HMM-162 on one side and HMM-261 on the other.[89][90]

- National Museum of the Marine Corps Quantico, Virginia has a walk-through exhibit containing the rear half of a CH-46D displayed as the former #153986 (c/n 2337) YK-13 from HMM-364 with their logo, The Purple Fox.[91] The front half of the aircraft was used as a training aid display for HMX-1.[92][93]

- Patriots Point Naval and Maritime Museum in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, has CH-46E #154009 (c/n 2360) of HMM-164.[94][95]

- Veterans Museum Dyersburg Army Air Base in Halls, Tennessee.[96]

See also

- Related development

- CH-47 Chinook

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Piasecki H-25

- Sikorsky S-61

- Yakovlev Yak-24

- Related lists

References

- Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 CH-46 history page, U.S. Navy, 16 November 2000.

- ↑ Apostolo, Giorgio. "Boeing Vertol Model 107". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Helicopters. New York: Bonanza Books. 1984. ISBN 978-0-517-43935-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Donald 1997, p. 175.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Spenser, Jay P. Whirlybirds, A History of the U.S. Helicopter Pioneers. University of Washington Press, 1998. ISBN 0-295-97699-3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Tandem Twosome", Vertical Magazine, February–March 2007.

- ↑ "US Air Force CH-46B". Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 "Boeing Sea Knight". Vectorsite.net, 1 August 2011.

- ↑ Rottman and Hook 2007, p. 10.

- ↑ Eden, Paul, ed. "Boeing-Vertol H-46 Sea Knight", Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- ↑ King, Tim (23 April 2012). "Vietnam's Helicopter Valley: Graveyard of Marine CH-46's". Salem-News.com (Salem, OR). Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ "Boeing Vertol 107 – CH-46 Sea Knight". Helicopter History Site. Helis.com.

- ↑ "Ask A Marine". HMM-364 Purple Foxy Ladies.

- ↑ Hamilton, Molly. "Former CH-46 Sea Knight pilot lends expertise to Vietnam Experience Exhibit." patriotspoint.org, 3 November 2014.

- ↑ Dunstan 2003, pp. 182-184.

- ↑ "CH-46 Sea Knight." National Naval Aviation Museum, Retrieved: 23 March 2014.

- ↑ Darrow Robert A.. Historical, Logistical, Political and Technical Aspects of the Herbicide/Defoliant Program, 1967-1971. Plant Sciences Laboratories, US Army Chemical Corps, Fort Detrick, Frederick MD, September 1971. p. 30. A Resume of the Activities of the Subcommittee on Defoliation/Anticrop Systems (Vegetation Control Subcommittee) for the Joint Technical Coordinating Group/Chemical-Biological.

- ↑ "0800031 Special Atomic Demolition Munition (SADM) Delivery by Parachutist/Swimmer/ Declassified U.S. Nuclear Test Film #31". osti.gov. Department of Energy. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ NUWAX-83 training scenario film.

- ↑ Stout, Jay A. Hammer from Above, Marine Air Combat Over Iraq. Ballantine Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0-89141-871-9.

- ↑ Cheeca, Rocky. "Evacuating the Injured." Air & Space Magazine, September 2012.

- ↑ Murray and Scales 2005, p. 272.

- ↑ Warwick, Graham. "Picture: US Marine Corps tests anti-missile system for Boeing CH-46 Sea Knight as Iraq helicopter shoot-downs mount." Flight International, 23 February 2007.

- ↑ "Major Acquisition Programs – Aviation Combat Element Programs" (PDF). Headquarters Marine Corps. 2006.

- ↑ White, LCpl Samuel. "VMM-263 ready to write next chapter in Osprey program". U.S. Marine Corps.

- ↑ Venerable 'Sea Knight' Makes Goodbye Flights - Military.com, 3 October 2014

- ↑ Marines Bid ‘Phrog’ Farewell to Last Active CH-46E Sea Knight Squadron - News.USNI.org, 10 April 2015

- ↑ Milberry, Larry: Sixty Years – The RCAF and Air Command 1924–1984, p. 472. McGraw Hill Ryerson, 1984. ISBN 0-07-549484-1

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Canada Aviation and Space Museum (n.d.). "Boeing Vertol CH-113 Labrador". Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ "Columbia Helicopters Acquires eight CH-113 Labrador helicopters from Canadian military". RotorHub. RotorHub.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Eichel, Garth. "Columbia Helicopters". Vertical Magazine, February–March 2007.

- ↑ "Happy birthday to Columbia Helicopters! Oregon-based company celebrates its 50th anniversary" Vertical (magazine), 18 April 2007. Retrieved: 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "The hover barge" Columbia Helicopters. Retrieved: 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Type Certificate Data Sheet No. 1H16" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 17 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ↑ Boeing BV-107 helicopters built. Helis.com

- ↑ Boeing BV-107/II helicopters built. Helis.com

- ↑ Boeing H-46 helicopters built. Helis.com

- ↑ LCpl Payne, Doug (20 December 2007). "Pedro retires last HH-46Ds" (PDF). The Windsock (Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, NC). pp. A1 & A3. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ↑ "Photo of Boeing Model 360 with CH-46X tail markings". Airport-data.com. 2007-06-17. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ↑ CH-113 Labrador. Helis.com.

- ↑ CH-113A Voyageur. Helis.com.

- ↑ HKP 4A. Helis.com.

- ↑ HKP 4B. Helis.com.

- ↑ HKP 4D. Helis.com.

- ↑ "database for all Kawasaki KV-107 helicopters built". Helis.com. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ↑ "Old Phrogs get new life". 2012, Gannett Government Media Corporation. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ↑ "Helifor Fleet". helifor.com. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Columbia 107-II". colheli.com. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "World's Air Forces 1981 pg. 330". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Boeing Vertol CH-113 Labrador". Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 66". Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ↑ "警視庁 – Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department". Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ↑ "World Air Forces 2004 pg. 83". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Kawasaki/Vertol KV107 operators". Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 91". Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ↑ "Thai aviation history". Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- ↑ "New York Airways Boeing-Vertol V 107 N6672D". Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ↑ "HEAVY-LIFT HELPERS". Vertical magazine. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ↑ "Vietnam-era Marine helo flies into history". utsandiego.com. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ "HMX-1". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "VMR-1". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron-262 [HMM-262]". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron-265". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron-268". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron-364". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 764". tripod.com. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Marine Medium Helicopter Training Squadron 164". tripod.com. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ Vietnam-era Marine helo flies into history

- ↑ "World Air Forces 2004 pg. 96". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ Polmar, Norman (2005). [page 384 The Naval Institute Guide to the Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet] (18th ed.). p. 384. ISBN 978-1591146858. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ↑ Shulimson, Jack (1982). U.S. Marines in Vietnam: An Expanding War, 1966 (Marine Corps Vietnam Operational Historical Series). Marine Corps Association. pp. 164–5. ASIN B000L34A0C.

- ↑ "680606 HMM-165 Vietnam". USMC Combat Helicopter Association. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Charles (1988). US Marines in Vietnam High Mobility and Standdown 1969. History and Museums Division Headquarters United States Marine Corps. p. 55. ISBN 9781494287627.

- ↑ A Tailhook of a Different Kind... check-six.com

- ↑ Frawley, Gerald. The International Directory of Military Aircraft, 2002/2003, p. 48. Fyshwick, ACT, Australia: Aerospace Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-875671-55-2.

- ↑ National Air Force Museum of Canada (2010). "Labrador". Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ↑ Comox Air Force Museum (December 2009). "News". Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Display aircraft JASDF Hamamatsu Air Base Publication Center

- ↑ Display helicopters Kakamigahara Aerospace Science Museum

- ↑ Museum Outline Kawasaki Good Times World

- ↑ "JA9555". Chakkiri.com. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ↑ Aircraft at Museum. Aeroseum

- ↑ "boeing-vertol hkp4b - Helicopter Database". Helis.com. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ↑ "Boeing-Vertol CH-46D c/n 2410- Helicopter Database". Helis.com. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ Myers, Phil (31 March 2012). "HMM-165 "Lady Ace 09″ Dedication". militaryaviationjournal.com/. Military Aviation Journal. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ "Boeing-Vertol CH-46D c/n 2040 - Helicopter Database". Helis.com. Retrieved 2014-12-13.

- ↑ "Boeing-Vertol CH-46D c/n 2102 - Helicopter Database". Helis.com. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ "Boeing-Vertol CH-46D c/n 2225 - Helicopter Database". Helis.com. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ "Boeing-Vertol CH-46D (c/n 2300) - Helicopter Database". Helis.com. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ Lingafelt, Jared (6 November 2014). "MV-22 dedicated to Aviation Memorial". The Globe (Jacksonville, NC). Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ "Boeing-Vertol CH-46D (c/n 2337) - Helicopter Database". Helis.com. Retrieved 2014-12-13.

- ↑ Helicopter halved to serve as museum exhibit, training aid

- ↑ Swifty Finds Permanent Home

- ↑ "Boeing-Vertol CH-46D c/n 2360 - Helicopter Database". Helis.com. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ Patriots Point Adds 1967 CH-46D Helicopter

- ↑ Veterans Museum welcomes new exhibit

- Bibliography

- Andrade, John U.S.Military Aircraft Designations and Serials since 1909. Midland Counties Publications, 1979. ISBN 0-904597-22-9.

- Andrade, John. Militair 1982. London: Aviation Press Limited, 1982. ISBN 0-907898-01-7.

- Donald, David ed. "Boeing Vertol Model 107 (H-46 Sea Knight)" The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft, Barnes & Nobel Books, 1997. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- Dunstan, Simon. Vietnam Choppers: Helicopters in Battle 1950-1975, Osprey Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84176-796-4.

- Murray, Williamson and Robert H. Scales. The Iraq War. Harvard University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-67450-412-7.

- Rottman, Gordon and Adam Hook. Vietnam Airmobile Warfare Tactics. Osprey Publishing, 2007. ISBN 1-84603-136-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to CH-46 Sea Knight. |

- CH-46D/E Sea Knight and CH-46 history pages on U.S. Navy site; CH-46 page on USMC site

- CH-46 product page and CH-46 history page on Boeing.com

- Columbia Helicopters — Largest Civilian Operator of BV/KV Model 107

- Boeing Vertol 107 & H-46 Sea Knight on Airliners.net

- Detail List of CH-113 Labradors & Voyageurs

- Kawasaki Helicopter Services (S.A.) Ltd.

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||