Boeing B-29 Superfortress

| B-29 Superfortress | |

|---|---|

| |

| A USAAF B-29 Superfortress | |

| Role | Strategic bomber |

| Manufacturer | Boeing |

| First flight | 21 September 1942[1] |

| Introduction | 8 May 1944 |

| Retired | 21 June 1960 |

| Status | 1 airworthy, 1 in restoration, and several in whole or part in museum collections |

| Primary users | United States Army Air Forces United States Air Force Royal Air Force |

| Produced | 1943–1946[2] |

| Number built | 3,970 |

| Unit cost |

US$639,188[3] |

| Variants | All models Boeing KB-29 Superfortress XB-39 Superfortress Boeing XB-44 Superfortress Boeing B-50 Superfortress Tupolev Tu-4 |

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a four-engine propeller-driven heavy bomber designed by Boeing that was flown primarily by the United States toward the end of World War II and during the Korean War. It was one of the largest aircraft to have seen service during World War II and a very advanced bomber for its time, with features such as a pressurized cabin, an electronic fire-control system, and a quartet of remote-controlled machine-gun turrets operated by the fire-control system in addition to its defensive tail gun installation. The name "Superfortress" was derived from that of its well-known predecessor, the B-17 Flying Fortress. Although designed as a high-altitude strategic bomber, and initially used in this role against the Empire of Japan, these attacks proved to be disappointing; as a result the B-29 became the primary aircraft used in the American firebombing campaign, and was used extensively in low-altitude night-time incendiary bombing missions. One of the B-29's final roles during World War II was carrying out the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Due to the B-29's highly advanced design for its time, unlike many other World War II-era bombers, the Superfortress remained in service long after the war ended, with a few even being employed as flying television transmitters for the Stratovision company. The B-29 served in various roles throughout the 1950s. The Royal Air Force flew the B-29 and used the name Washington for the type, replacing them in 1953 with the Canberra jet bomber, and the Soviet Union produced an unlicensed reverse-engineered copy as the Tupolev Tu-4. The B-29 was the progenitor of a series of Boeing-built bombers, transports, tankers, reconnaissance aircraft and trainers including the B-50 Superfortress (the first aircraft to fly around the world non-stop) which was essentially a re-engined B-29. The type was finally retired in the early 1960s, with 3,970 aircraft in all built. While dozens of B-29s have survived through today as static displays, only one, Fifi, remains on active flying status.

A transport derived from the B-29 was the C-97, first flown in 1944, followed by its commercial airliner variant, the Boeing Model 377 Stratocruiser in 1947. This bomber-to-airliner derivation was similar to the B-17/Model 307 evolution. The tanker variant of the B-29 was introduced in 1948 as the KB-29, followed by the Model 377-derivative KC-97 introduced in 1950. A heavily modified line of outsized-cargo variants of the B-29-derived Stratocruiser is the Guppy / Mini Guppy / Super Guppy which remain in service today with operators such as NASA.

Design and development

Boeing began work on pressurized long-range bombers in 1938, when, in response to a United States Army Air Corps request, it produced a design study for the Model 334, a pressurized derivative of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress with nosewheel undercarriage. Although the Air Corps did not have money to pursue the design, Boeing continued development with its own funds as a private venture,[4] so that when, in December 1939, the Air Corps issued a formal specification for a so-called "superbomber", capable of delivering 20,000 lb (9,100 kg) of bombs to a target 2,667 mi (4,290 km) away and capable of flying at a speed of 400 mph (640 km/h), they formed a starting point for Boeing's response.[5]

Boeing submitted its Model 345 on 11 May 1940,[6] in competition with designs from Consolidated Aircraft (the Model 33, later to become the B-32),[7] Lockheed (the Lockheed XB-30),[8] and Douglas (the Douglas XB-31).[9] Douglas and Lockheed soon abandoned work on their projects, but Boeing received an order for two flying prototypes, given the designation XB-29, and an airframe for static testing on 24 August 1940, with the order being revised to add a third flying aircraft on 14 December. Consolidated continued to work on its Model 33 as it was seen by the Air Corps as a backup in case of problems with Boeing's design.[10] An initial production order for 14 service test aircraft and 250 production bombers was placed in May 1941,[11] this being increased to 500 aircraft in January 1942.[6] The B-29 featured a fuselage design with circular cross-section for strength. The need for pressurization in the cockpit area also led to the B-29 having the only "stepless" cockpit design, without a separate windscreen for the pilot, on an American combat aircraft of World War II.

Manufacturing the B-29 was a complex task. It involved four main-assembly factories: a pair of Boeing operated plants at Renton, Washington (Boeing Renton), and Wichita, Kansas (actual Spirit AeroSystems), a Bell plant at Marietta, Georgia ("Bell-Atlanta"), and a Martin plant at Omaha, Nebraska ("Martin-Omaha" - Offutt Field).[6][12] Thousands of subcontractors were involved in the project.[13] The first prototype made its maiden flight from Boeing Field, Seattle on 21 September 1942.[12] Because of the aircraft's highly advanced design, challenging requirements, and immense pressure for production, development was deeply troubled. The second prototype, which, unlike the unarmed first, was fitted with a Sperry defensive armament system using remote-controlled gun turrets sighted by periscopes,[14] first flew on 30 December 1942, this flight being terminated due to a serious engine fire. On 18 February 1943, the second prototype experienced an engine fire and crashed.[15] Changes to the production craft came so often and so fast that in early 1944, B-29s flew from the production lines directly to modification depots for extensive rebuilds to incorporate the latest changes. The USAAF–operated modification depots struggled to cope with the scale of work required, with a lack of hangars capable of housing the B-29 combined with freezing cold weather further delaying the modification, such that at the end of 1943, although almost 100 aircraft had been delivered, only 15 were airworthy.[16][17] This prompted an intervention by General Hap Arnold to resolve the problem, with production personnel being sent from the factories to the modification centers to speed modification of sufficient aircraft to equip the first Bomb Groups in what became known as the "Battle of Kansas". This resulted in 150 aircraft being modified in the six weeks between 10 March and 15 April 1944.[18][19]

The most common cause of maintenance headaches and catastrophic failures were the engines.[18] Although the Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone radial engines later became a trustworthy workhorse in large piston-engined aircraft, early models were beset with dangerous reliability problems. This problem was not fully cured until the aircraft was fitted with the more powerful Pratt & Whitney R-4360 "Wasp Major" in the B-29D/B-50 program, which arrived too late for World War II. Interim measures included cuffs placed on propeller blades to divert a greater flow of cooling air into the intakes, which had baffles installed to direct a stream of air onto the exhaust valves. Oil flow to the valves was also increased, asbestos baffles installed around rubber push rod fittings to prevent oil loss, thorough pre-flight inspections made to detect unseated valves, and frequent replacement of the uppermost five cylinders (every 25 hours of engine time) and the entire engines (every 75 hours).[N 1][18]

Pilots, including the present day pilots of the Commemorative Air Force’s Fifi, the last remaining flying B-29, describe flight after takeoff as being an urgent struggle for airspeed (generally, flight after takeoff should consist of striving for altitude). Radial engines need airflow to keep them cool, and failure to get up to speed as soon as possible could result in an engine failure and risk of fire. One useful technique was to check the magnetos while already on takeoff roll rather than during a conventional static engine-runup before takeoff.[20]

In wartime, the B-29 was capable of flight at altitudes up to 31,850 feet (9,710 m),[21] at speeds of up to 350 mph (560 km/h) (true airspeed). This was its best defense, because Japanese fighters could barely reach that altitude, and few could catch the B-29 even if they did attain that altitude. Only the heaviest of anti-aircraft weapons could reach it, and since the Axis forces did not have proximity fuzes, hitting or damaging the aircraft from the ground in combat proved difficult.

The B-29's revolutionary Central Fire Control system included four remotely controlled turrets armed with two .50 Browning M2 machine guns each.[N 2] All weapons were aimed electronically from five sighting stations located in the nose and tail positions and three Plexiglas blisters in the central fuselage.[N 3] Five General Electric analog computers (one dedicated to each sight) increased the weapons' accuracy by compensating for factors such as airspeed, lead, gravity, temperature and humidity. The computers also allowed a single gunner to operate two or more turrets (including tail guns) simultaneously. The gunner in the upper position acted as fire control officer, managing the distribution of turrets among the other gunners during combat.[22][23][24][25]

In early 1945, with a change of role from high-altitude day bomber to low-altitude night bomber, LeMay reportedly ordered the removal of most of the defensive armament and remote-controlled sighting equipment from his B-29s so that they could carry greater fuel and bomb loads.[26] As a consequence of this requirement, Bell Marietta (BM) produced a series of 311 B-29Bs that had turrets and sighting equipment removed, except for the tail position, which initially had the two .50 cal Browning machine guns and single M2 cannon with the APG-15 radar fitted as standard. This armament was quickly changed to three .50 caliber Brownings. This version also had an improved APQ-7 "Eagle" bombing-through-overcast radar fitted in an airfoil shaped radome under the fuselage. Most of these aircraft were assigned to the 315th Bomb Wing, Northwest Field, Guam.[27]

The crew enjoyed, for the first time in a bomber, full-pressurization comfort. This first-ever cabin pressure system for an Allied production bomber was developed for the B-29 by Garrett AiResearch. [N 4] The nose and the cockpit were pressurized, but the designers were faced with deciding whether to have bomb bays that were not pressurized, between fore and aft pressurized sections, or a fully pressurized fuselage with the need to de-pressurize to drop their loads. The decision was taken to have a long tunnel over the two bomb bays so that crews could crawl back and forth between the fore and aft sections, with both areas and the tunnel pressurized. The bomb bays were not pressurized.[28]

Operational history

World War II

The initial plan, implemented at the direction of President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a promise to China and called Operation Matterhorn, was to use B-29s to attack Japan from four forward bases in southern China, with five main bases in India, and to attack other targets in the region from China and India as needed.[29] The Chengdu region was eventually chosen over the Guilin region to avoid having to raise, equip, and train 50 Chinese divisions to protect the advanced bases from Japanese ground attack.[30] The XX Bomber Command, initially intended to be two combat wings of four groups each, was reduced to a single wing of four groups because of the lack of availability of aircraft, automatically limiting the effectiveness of any attacks from China.

This was an extremely costly scheme, as there was no overland connection available between India and China, and all supplies had to be flown over the Himalayas, either by transport aircraft or by the B-29s themselves, with some aircraft being stripped of armor and guns and used to deliver fuel. B-29s started to arrive in India in early April 1944. The first B-29 flight to airfields in China (over the Himalayas, or "The Hump") took place on 24 April 1944. The first B-29 combat mission was flown on 5 June 1944, with 77 out of 98 B-29s launched from India bombing the railroad shops in Bangkok and elsewhere in Thailand. Five B-29s were lost during the mission, none to hostile fire.[29][31]

Forward base in China

On 5 June 1944, B-29s raided Bangkok, in what is reported as a test before being deployed against the Japanese home islands. Sources do not report from where they launched, and vary as to the numbers involved—77, 98, and 114 being claimed. Targets were Bangkok's Memorial Bridge and a major power plant. Bombs fell over two kilometres away, damaged no civilian structures, but destroyed some tram lines and destroyed both a Japanese military hospital and the Japanese secret police headquarters.[32] On 15 June 1944, 68 B-29s took off from bases around Chengdu 47 of which reached and bombed the Imperial Iron and Steel Works at Yahata, Japan. This was the first attack on Japanese islands since the Doolittle raid in April 1942.[33] The first B-29 combat losses occurred during this raid, with one B-29 destroyed on the ground by Japanese fighters after an emergency landing in China,<ref name="AAFWW" v5p101">Craven and Cate 1983, p. 101.</ref> one lost to anti-aircraft fire over Yawata, and another, the Stockett's Rocket (after Capt. Marvin M. Stockett, Aircraft Commander) B-29-1-BW 42-6261,[N 5] disappeared after takeoff from Chakulia, India, over the Himalayas (12 KIA, 11 crew and one passenger)(Source: 20th Bomb Group Assn.) This raid, which did little damage to the target, with only one bomb striking the target factory complex,[35] nearly exhausted fuel stocks at the Chengdu B-29 bases, resulting in a slow-down of operations until the fuel stockpiles could be replenished.[36] Starting in July, the raids against Japan from Chinese airfields continued at relatively low intensity. Japan was bombed on: 7 July 1944 (14 B-29s), 29 July (70+), 10 August (24), 20 August (61), 8 September (90), 26 September (83), 25 October (59), 12 November (29), 21 November (61), 19 December (36) and for the last time on 6 January 1945 (49).

The tactic of using aircraft to ram American B-29s was first recorded on raid of 20 August 1944 on the steel factories at Yawata. Sergeant Shigeo Nobe of the 4th Sentai intentionally flew his Kawasaki Ki-45 into a B-29; debris from the explosion following this attack severely damaged another B-29, which also went down. Lost were Colonel Robert Clinksale's B-29-10-BW 42-6334 Gertrude C and Captain Ornell Stauffer's B-29-15-BW 42-6368 Calamity Sue, both from the 486th BG.[37] Several B-29s were destroyed in this way over the ensuing months. Although the term "Kamikaze" is often used to refer to the pilots conducting these attacks, the word was not used by the Japanese military.[38]

B-29s were withdrawn from airfields in China by the end of January 1945. Throughout this prior period, B-29 raids were also launched from China and India against many other targets throughout Southeast Asia, including a series of raids on Singapore and Thailand. On 2 November 1944, 55 B-29s raided Bangkok's Bang Sue marshalling yards in the largest raid of the war. Seven RTAF Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusas from Foong Bin (Air Group) 16 and 14 IJAAF Ki-43s attempted intercept. RTAF Flt Lt Therdsak Worrasap attacked a B-29, damaging it, but was shot down by return fire. One B-29 was lost, possibly the one damaged by Flt Lt Therdsak. [N 6] On 14 April 1945, a second B-29 raid on Bangkok destroyed two key power plants, and was the last major attack conducted against Thai targets.[32] The B-29 effort was gradually shifted to the new bases in the Mariana Islands in the Central Pacific, with the last B-29 combat mission from India flown on 29 March 1945.

New Mariana Islands air bases

In addition to the logistical problems associated with operations from China, the B-29 could only reach a limited part of Japan while flying from Chinese bases. The solution to this problem was to capture the Mariana Islands, which would bring targets such as Tokyo, about 1,500 mi (2,400 km) north of the Marianas within range of B-29 attacks. It was therefore agreed in December 1943 to seize the Marianas.[40]

Saipan was invaded by US forces on 15 June 1944, and despite a Japanese naval counterattack which led to the Battle of the Philippine Sea and heavy fighting on land, was secured by 9 July.[41] Operations followed against Guam and Tinian, with all three islands secured by August.[42]

Work began at once to construct air bases suitable for the B-29, commencing even before the end of ground fighting. [41] In all, five major air fields were built: two on the flat island of Tinian, one on Saipan, and two on Guam. Each was large enough to eventually accommodate a bomb wing consisting of four bomb groups, giving a total of 180 B-29s per airfield. [31] These bases, which could be supplied by ship, and unlike the bases in China, were not vulnerable to attacks by Japanese ground forces, became the launch sites for the large B-29 raids against Japan, in the final year of the war. The first B-29 arrived on Saipan on 12 October 1944, and the first combat mission was launched from there on 28 October 1944, with 14 B-29s attacking the Truk atoll. The first mission against Japan from bases in the Marianas, was flown on 24 November 1944, with 111 B-29s sent to attack Tokyo, with 73rd Bomb Wing wing commander Brigadier General Emmett O'Donnell, Jr. as mission command pilot in B-29 Dauntless Dotty, the first attack on the capital since the Doolittle Raid in April 1942. From that point, raids intensified, launched regularly until the end of the war. These attacks succeeded in devastating most large Japanese cities (with the exception of Kyoto and several others), and they gravely damaged Japan's war industries. Although less publicly appreciated, the mining of Japanese ports and shipping routes (Operation Starvation) carried out by B-29s from April 1945 significantly affected Japan's ability to support its population and move its troops.

The atomic bombs

Perhaps the most famous B-29s were the Silverplate series, which were modified to drop atomic bombs. The Silverplate aircraft were handpicked by Lieutenant Colonel Paul W. Tibbets for the mission, straight off the assembly line at the Omaha plant that was to become Offutt Air Force Base.

Enola Gay flown by Tibbets, dropped the first bomb, called Little Boy, on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. Enola Gay is fully restored and on display at the Smithsonian's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, outside Dulles Airport in Washington, D.C. Bockscar dropped the second bomb, called Fat Man, on Nagasaki three days later. Bockscar is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

Following the surrender of Japan, called V-J Day, B-29s were used for other purposes. A number supplied POWs with food and other necessities by dropping barrels of rations on Japanese POW camps. In September 1945, a long-distance flight was undertaken for public relations purposes: Generals Barney M. Giles, Curtis LeMay and Emmett O'Donnell, Jr. piloted three specially modified B-29s from Chitose Air Base in Hokkaidō to Chicago Municipal Airport, continuing to Washington, D.C., the farthest nonstop distance to that date flown by U.S. Army Air Forces aircraft and the first-ever nonstop flight from Japan to the U.S.[N 7][44] Two months later, Colonel Clarence S. Irvine commanded another modified B-29, Pacusan Dreamboat, in a world-record-breaking long-distance flight from Guam to Washington, D.C., traveling 7,916 miles (12,740 km) in 35 hours,[45] with a gross takeoff weight of 155,000 pounds (70,000 kg).[46] Almost a year later, in October 1946, the same B-29 flew 9,422 miles nonstop from Oahu, Hawaii to Cairo, Egypt in less than 40 hours, further proving the capability of routing airlines over the polar icecap.[47]

B-29s in Europe and Australia

Although considered for other theaters, and briefly evaluated in England, the B-29 was exclusively used in World War II in the Pacific Theatre. The use of YB-29-BW 41-36393, the so-named Hobo Queen, one of the service test aircraft flown around several British airfields in early 1944, was thought to be as a "disinformation" program intended to deceive the Germans into believing that the B-29 would be deployed to Europe.[19]

Postwar, several RAF Bomber Command squadrons were equipped with B-29s loaned from USAF stocks. The aircraft were known as the Washington B.1 in RAF service, and remained in service from March 1950 until the last bombers were returned in early 1954, having been replaced by deliveries of the English Electric Canberra bombers. Three Washingtons modified for ELINT duties and a standard bomber version used for support by No. 192 Squadron RAF were decommissioned in 1958 being replaced by de Havilland Comet aircraft.

Two British Washington B.1 aircraft were transferred to the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) in 1952. They were attached to the Aircraft Research and Development Unit and used in trials conducted on behalf of the British Ministry of Supply. Both aircraft were placed in storage in 1956 and were sold for scrap the next year.[48]

Soviet replication of the B-29

.jpg)

Following the limited service of the only Soviet-designed four-engined heavy bomber, the Petlyakov Pe-8 with the VVS starting in 1940, of which only some 93 examples were ever built, during 1944 and 1945 five B-29s made emergency landings in Soviet territory after bombing raids on Japanese Manchuria and Japan. In accordance with Soviet neutrality in the Pacific War, the bombers were interned and kept by the Soviets, despite American requests for their return and were, instead, used by the Soviets as a pattern for the Tupolev Tu-4.[49]

On 31 July 1944 Ramp Tramp (serial number 42-6256), of the 462nd (Very Heavy) Bomb Group was diverted to Vladivostok, Russia after an engine failed and the propeller could not be feathered.[N 8] This B-29 was part of a 100 aircraft raid against the Japanese Showa steel mill in Anshan, Manchuria.[49] On 20 August 1944, Cait Paomat (42-93829), flying from Chengdu, was damaged by anti-aircraft gunfire during a raid on the Yawata Iron Works. Due to the damage sustained, the crew elected to divert to the Soviet Union. The aircraft crashed in the foothills of Sikhote Alin Range east of Khabarovsk after the crew bailed out.

On 11 November 1944, during a night raid on Omura on Kyushu Japan, the General H.H. Arnold Special (42-6365) was damaged and forced to divert to Vladivostok in the Soviet Union. The crew was interned.[50] On 21 November 1944, Ding Hao (42-6358) was damaged during a raid on an aircraft factory at Omura, Japan, and was also forced to divert to Vladivostok.

The interned crews of these four B-29s were allowed to escape into American-occupied Iran in January 1945 but none of the B-29s was returned after Stalin ordered the Tupolev OKB to examine and copy the B-29, and produce a design ready for quantity production as soon as possible.[50][N 9]

Because aluminum in the USSR was supplied in different gauges from that available in the US (metric vs imperial),[49] the entire aircraft had to be extensively re-engineered. In addition, Tupolev substituted his own favored airfoil sections for those used by Boeing, with the Soviets themselves already having their own Wright R-1820-derived 18 cylinder radial engine, the Shvetsov ASh-73 of comparable power and displacement to the B-29's Duplex Cyclone radials available to power their B-29 clone aircraft. In 1947, the Soviets debuted both the Tupolev Tu-4 (NATO ASCC code named Bull), and the Tupolev Tu-70 transport variant. The Soviets used tail-gunner positions similar to the B-29 in many later bombers and transports.[51][N 10]

Between wars

While the end of World War II caused production of the B-29 to be phased out, with the last example completed by Boeing's Renton factory on 28 May 1946, and with many aircraft sent for storage and ultimately scrapping as surplus to requirements, the remaining B-29s formed the combat equipment of Strategic Air Command when it formed on 21 March 1946.[53] In particular, the "Silverplate" modified aircraft of the 509th Composite Group remained the only aircraft capable of delivering the atomic bomb, and so the unit was involved in the Operation Crossroads series of tests, with B-29 Dave's Dream dropping a "Fat Man"-type bomb in Test Able on 1 July 1946.[53]

The B-29s were outfitted with filtered air sampling scoops and monitored debris from above ground nuclear weapons testing by the United States and the USSR. The aircraft were also used for long-range weather reconnaissance (WB-29) and for signals intelligence gathering and photographic reconnaissance (RB-29).

Korean War and postwar service

The B-29 was used in 1950–53 in the Korean War. At first, the bomber was used in normal strategic day-bombing missions, though North Korea's few strategic targets and industries were quickly reduced to rubble. More importantly, in 1950 numbers of Soviet MiG-15 "Fagot" jet fighters appeared over Korea, and after the loss of 28 aircraft, future B-29 raids were restricted to night-only missions, largely in a supply-interdiction role. Over the course of the war, B-29s flew 20,000 sorties and dropped 200,000 tonnes (180,000 tons) of bombs. B-29 gunners were credited with shooting down 27 enemy aircraft.[54]

The B-29 was notable for dropping the large "Razon" and "Tarzon" radio-controlled bomb in Korea, mostly for demolishing major bridges, like the ones across the Yalu River, and for attacks on dams. The aircraft also was used for numerous leaflet drops in North Korea, such as those for Operation Moolah.[55]

A Superfortress of the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron flew the last B-29 mission of the war on 27 July 1953. Over the three years 16 B-29 and reconnaissance variants were lost to North Korean fighters, four to anti-aircraft fire and 14 to other operational causes.[56]

The B-29 was soon made obsolete by the development of jet engined fighter aircraft. With the arrival of the mammoth Convair B-36, the B-29 was reclassified as a medium bomber by the Air Force. However, the later B-50 Superfortress variant (which was initially designated B-29D) was good enough to handle auxiliary roles such as air-sea rescue, electronic intelligence gathering, air-to-air refueling, and weather reconnaissance. The B-50D was replaced in its primary role during the early 1950s by the Boeing B-47 Stratojet, which in turn was replaced by the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. The final active-duty KB-50 and WB-50 variants were phased out in the mid-1960s, with the final example retired in 1965. A total of 3,970 B-29s was built.

Variants

Unlike many other aircraft designed to play a similar role, the variants of the B-29 were all essentially the same. The developments made between the first prototype XB-29 and any of the three versions flown in combat were all minuscule, excluding the Silverplate models built for the Manhattan Project. The biggest differences were between variants modified for non-bomber missions. In addition to acting as cargo carriers, rescue aircraft, weather ships and trainers; some were used for odd purposes such as flying relay television transmitters under the name of Stratovision.

An example of a later variant of the B-29, the B-50 Superfortress (which was powered by four 3,500 hp (2,600 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-4360-35 Wasp Major engines), acted as the mothership for experimental parasite fighter aircraft, such as the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin and Republic F-84 Thunderjets as in flight lock on and offs. It was also used to develop the Airborne Early Warning program; it was the ancestor of various modern radar picket aircraft. A B-29 with the original Wright Duplex Cyclone powerplants was used to air-launch the famous Bell X-1 supersonic research rocket aircraft, as well as Cherokee rockets for the testing of ejection seats.[57]

Some B-29s were modified to act as test beds for various new systems or special conditions, including fire-control systems, cold-weather operations, and various armament configurations. Several converted B-29s were used to experiment with aerial refueling and re-designated as KB-29s. Perhaps the most important tests were conducted by the XB-29G; it carried prototype jet engines in its bomb bay, and lowered them into the air stream to conduct measurements.

Operators

- Royal Australian Air Force (two former RAF aircraft for trials)

- Royal Air Force (87 loaned from the USAF as the Washington B.1)

- United States Army Air Forces

- United States Air Force

- United States Navy (four former USAF aircraft designated as P2B patrol bombers)

- Soviet Air Forces (three captured USAAF)

Survivors

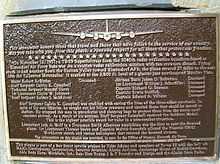

Twenty-two B-29s are preserved at various museums worldwide, including one flying example; Fifi, which belongs to the Commemorative Air Force, along with four complete airframes either in storage or under restoration (including one to airworthy), eight partial airframes in storage or under restoration, and four known wreck sites.[58] Only two of the 22 museum aircraft are outside the United States, one is the B-29A "It's Hawg Wild" in the American Air Museum at the Imperial War Museum Duxford in the United Kingdom, the other at the KAI Aerospace Museum in Sachon, South Korea. The B-29, "Miss Marilyn Gay", which flew 27 successful bombing missions mainly over Japan during the Second World War, and five POW relief missions is displayed at Dobbins Air Reserve Base in Georgia. There is a restored B-29A, "Jack's Hack," located as part of the 58th Bomb Wing Memorial the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, CT. The Enola Gay (nose number 82) the B-29 that dropped the first atomic bomb, was fully restored and placed on display at the Smithsonian's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Air & Space Museum near Washington Dulles International Airport in 2003. Similarly, the weapons delivery aircraft for the Nagasaki raid deploying the Fat Man, the Bockscar (nose number 77) is restored and on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.

Accidents and incidents

Notable B-29 accidents and incidents include a crash of the plane near Clovis, New Mexico on Friday evening, 10 November 1944 wherein all 15 members of the crew were killed; 1948 Waycross B-29 crash, which resulted in the United States v. Reynolds lawsuit regarding State Secrets Privilege, the 1948 Lake Mead Boeing B-29 crash and the 1953 "Tip Tow" crash. Another well-known crash took place in 1946 near Clingmans Dome on the border of North Carolina and Tennessee. On 11 April 1950 a B-29 departed Kirtland Air Force Base at 9:38 p.m. and crashed into a mountain on Manzano Base approximately three minutes later, killing the crew. Detonators were installed in the nuclear bomb on the aircraft. The bomb case was demolished and some high-explosive (HE) material burned in the gasoline fire. Other pieces of unburned HE were scattered throughout the wreckage. Four spare detonators in their carrying case were recovered undamaged. There were no contamination or recovery problems. The recovered components were returned to the Atomic Energy Commission.[59] Both the weapon and the capsule of nuclear material were on board the aircraft but the capsule was not inserted for safety reasons. A nuclear detonation was not possible. [60]

Specifications (B-29)

Data from Quest for Performance[61]

General characteristics

- Crew: 11 (Pilot, Co-pilot, Bombardier, Flight Engineer, Navigator, Radio Operator, Radar Observer, Right Gunner, Left Gunner, Central Fire Control, Tail Gunner)

- Length: 99 ft 0 in (30.18 m)

- Wingspan: 141 ft 3 in (43.06 m)

- Height: 27 ft 9 in (8.45 m)

- Wing area: 1,736 sq ft (161.3 m²)

- Aspect ratio: 11.50:1

- Empty weight: 74,500 lb (33,800 kg)

- Loaded weight: 120,000 lb (54,000 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 133,500 lb (60,560 kg) ; 135,000 lb plus combat load

- Powerplant: 4 × Wright R-3350 -23 and 23A Duplex Cyclone turbosupercharged radial engines, 2,200 hp (1,640 kW) each

- Zero-lift drag coefficient: 0.0241

- Drag area: 41.16 ft² (3.82 m²)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 357 mph (310 knots, 574 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 220 mph (190 knots, 350 km/h)

- Stall speed: 105 mph (91 knots, 170 km/h)

- Range: 3,250 mi (2,820 nmi, 5,230 km)

- Ferry range: 5,600 mi (4,900 nmi, 9,000 km, <ref group"N">record 7,916 miles, 12,740 km</ref>)

- Service ceiling: 31850 ft [21] (9,710 m)

- Rate of climb: 900 ft/min (4.6 m/s)

- Wing loading: 69.12 lb/sqft (337 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.073 hp/lb (121 W/kg)

- Lift-to-drag ratio: 16.8

Armament

- Guns:

- Bombs: 20,000 lb (9,000 kg) standard loadout.[63]

See also

- Silverplate – the atom bomb-dedicated B-29 version

- Boeing B-29 Superfortress variants

- Bockscar

- Enola Gay

- FIFI

- Kee Bird

- Straight Flush

- AN/APQ-13

- United States v. Reynolds

- ASM-A-1 Tarzon

- Related development

- Boeing KB-29

- Boeing XB-39 Superfortress

- Boeing XB-44 Superfortress

- Boeing B-50 Superfortress

- Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter

- Boeing 377

- Tupolev Tu-4

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Avro Lancaster

- Amerika Bomber

- Consolidated B-32 Dominator

- Douglas XB-31

- Heinkel He 277

- Junkers Ju 390

- Lockheed XB-30

- Messerschmitt Me 264

- Victory Bomber

- Related lists

- List of aircraft of World War II

- List of bomber aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States

References

Notes

- ↑ As efforts were made to eradicate the problems a succession of engine models were fitted to B-29s. B-29 production started with the −23, which were all modified to the "war engine" −23A. Other versions were −41 (B-29A), −57, −59.

- ↑ The forward upper turret's armament was later doubled to four .50 Brownings.

- ↑ The nose sighting station was operated by the bombardier

- ↑ Boeing had previously built the 307 Stratoliner, which was the first commercial airliner with a fully pressurized cabin. Only 10 of these aircraft were built. While other aircraft such as the Ju 86P were pressurized, the B-29 was designed from the outset with a pressurized system.

- ↑ The suffix −1-BW indicates that this B-29 was from the first production batch of B-29s manufactured at the Boeing, Wichita plant. Other suffixes are BA = Bell, Atlanta; BN = Boeing, Renton, Washington; MO = Martin, Omaha, Nebraska.[34]

- ↑ The biggest raid on Bangkok during the war occurred on 2 November 1944, when the marshalling yards at Bang Sue were raided by 55 B-29s ...[39]

- ↑ "The straight line distance between Chitose Japanese Air Self Defense Force and Chicago, Chicago Midway Airport is approximately 5,839 miles or 9,397 kilometers."[43]

- ↑ The drag of the windmilling propeller critically reduced the range of the B-29. Because of this "Ramp Tramp" was unable to reach the home-base at Chengdu, China, and the pilot opted to head for Vladivostok.

- ↑ Ramp Tramp was also used during 1948-49 as a drop ship for underwing launching of 346P glider. The 346P was a development of the German DFS 346 rocket-powered aircraft. The complete wing and engines of Cait Paomat were later incorporated into the sole Tupolev Tu-70 transport aircraft.

- ↑ The Soviets interned another B-29 when, on 29 August 1945, a Soviet Air Force Yak-9 damaged a B-29 dropping supplies to a POW camp in Korea, and forced it to land at Konan (now Hŭngnam), North Korea. The 13-man crew of the B-29 was not injured in the attack, and was released after being interned for 13 days.[52]

- ↑ For the B-29B-BW all armament and sighting equipment was removed except for tail position; initially 2 x .50 in M2/AN and 1× 20 mm M2 cannon, later 3 x 2 x .50 in M2/AN with APG-15 gun-laying radar fitted as standard.

Citations

- ↑ LeMay and Yenne 1988, p. 60.

- ↑ "Boeing B-29." Boeing. Retrieved: 5 August 2010.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, p. 486.

- ↑ Bowers 1989, p. 318.

- ↑ Willis 2007, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Bowers 1989, p. 319.

- ↑ Wegg 1990, p. 91.

- ↑ "Factsheet: Lockheed XB-30". National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- ↑ Francillon 1979, p. 713.

- ↑ Willis 2007, p. 138.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, p. 480.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Bowers 1989, p. 322.

- ↑ Willis 2007, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Brown 1977, p. 80.

- ↑ Peacock Air International August 1989, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Willis 2007, p. 144.

- ↑ Peacock Air International August 1989, p. 76.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Knaack 1988, p. 484.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Bowers 1989, p. 323.

- ↑ Gardner, Fred Carl. "A Year in the B-29 Superfortress." Fred Carl Gardner's website, updated 1 May 2005. Retrieved: 11 April 2009.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "B-29 Superfortress". Boeing. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ↑ Brown 1977, pp. 80–83.

- ↑ Williams and Gustin 2003, pp. 164–166.

- ↑ "B-29 Gunnery Brain Aims Six Guns at Once." Popular Mechanics, February 1945, p. 26.

- ↑ "Central Station Fire Control and the B-29 Remote Control Turret System" twinbeech.com

- ↑ Herman 2012, p. 327.

- ↑ "History of 315 BW". 315bw.org. Retrieved: 19 June 2008.

- ↑ Mann 2009, p. 103.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Willis 2007, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Craven and Cate 1983, pp. 18–22.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Peacock Air International August 1989, p. 87.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Stearn, Duncan. "The air war over Thailand, 1941-1945; Part Two, The Allies attack Thailand, 1942-1945." Pattaya Mail, Volume XI, Issue 21, 30 May – 5 June 2003. Retrieved: 18 February 2012.

- ↑ Craven and Cate 1983, p. 100.

- ↑ "List of B-29 and B-50 production." warbird-central.com. Retrieved: 16 June 2008.

- ↑ Willis 2007, p. 145.

- ↑ Craven and Cate 1983, pp. 101, 103.

- ↑ "Pacific War Chronology: August 1944." att.net. Retrieved: 12 June 2008.

- ↑ tokkotai.or.jp/ "Japanese website dedicated to the Tokkotai JAAF and JNAF." tokkotai.or.jp. Retrieved: 7 June 2008.

- ↑ Forsgren, Jan. "Japanese Aircraft In Royal Thai Air Force and Royal Thai Navy Service During WWII." Japanese Aircraft, Ships, & Historical Research, 21 July 2004. Retrieved: 18 February 2012.

- ↑ Willis 2007, pp. 145–146.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Willis 2007, p. 146.

- ↑ Dear and Foot 1995, p. 718.

- ↑ "How Far Is It?" Findlocalweather.com. Retrieved: 8 June 2009.

- ↑ Potts, J. Ivan, Jr. "Chapter: The Japan to Washington Flight." Remembrance of War: The Experiences of a B-29 Pilot in World War II. Shelbyville, Tennessee: J.I. Potts & Associates, 1995. Retrieved: 8 June 2009.

- ↑ "Monday, January 01, 1940 – Saturday, December 31, 1949." History Milestones ( US Air Force). Retrieved: 21 October 2010.

- ↑ Mayo, Weyland. "B-29s Set Speed, Altitude, Distance Records." b-29s-over-korea.com. Retrieved: 21 October 2010.

- ↑ "Inside The Dreamboat." Popular Science, December 1946 interview with crew about planning for flight.

- ↑ "A76: Boeing Washington." RAAF Museum. Retrieved: 28 January 2012.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 "Tu-4 "Bull" and Ramp Tramp." Monino Aviation. Retrieved: 1 November 2009.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Lednicer, David. "Intrusions, Overflights, Shootdowns and Defections During the Cold War and Thereafter." David Lednicer, 16 April 2011. Retrieved: 31 July 2011.

- ↑ "Russian B-29 Clone – The TU-4 Story." at the Wayback Machine (archived August 9, 2008) B-29.net. Retrieved: 20 July 2011

- ↑ Streifer, Bill and Irek Sabitov. "The Flight of the Hog Wild B-29 (WWII): The day the world went cold." Jia Educational Products, Inc., 2011. Retrieved: 28 November 2011.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Peacock Air International September 1989, p. 141.

- ↑ Futrell et al. 1976.

- ↑ United States Air Force operations in the Korean conflict, 1 July 1952 – 27 July 1953. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: USAF Historical Division, 1956, p. 62.

- ↑ Wheeler 1992, p. 84.

- ↑ Shinabery, Michael. "Whoosh failures were 'instructive'". 26 October 2008. Alamogordo Daily News. Accessed 2014-05-17.

- ↑ Weeks, John A. III. "B-29: The Superfortress Survivors". johnweeks.com, 2009. Retrieved: 17 July 2009.

- ↑ Atomic Energy Commission.

- ↑ Department of Defense, Narrative Summaries of Accidents Involving U.S. Nuclear Weapons, 1950-1980

- ↑ Loftin, LK, Jr. Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft. NASA SP-468. Retrieved: 22 April 2006.

- ↑ AAF manual No. 50-9: Pilot's Flight Operating Instructions for Army model B-29, 25 January 1944, page 40; Armament

- ↑ "The bombload of the B-29 eventually reached 9000 kg (20000 lb)" (Lewis 1994, p. 4)

Bibliography

- Anderton, David A. B-29 Superfortress at War. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Ltd., 1978. ISBN 0-7110-0881-7.

- Berger, Carl. B29: The Superfortress. New York: Ballantine Books, 1970. ISBN 0-345-24994-1.

- Birdsall, Steve. B-29 Superfortress in Action (Aircraft in Action 31). Carrolton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1977. ISBN 0-89747-030-3.

- Birdsall, Steve. Saga of the Superfortress: The Dramatic Story of the B-29 and the Twentieth Air Force. London: Sidgewick & Jackson Limited, 1991. ISBN 0-283-98786-3.

- Birdsall, Steve. Superfortress: The Boeing B-29. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1980. ISBN 0-89747-104-0.

- Bowers, Peter M. Boeing Aircraft since 1916. London: Putnam, 1989. ISBN 0-85177-804-6.

- Bowers, Peter M. Boeing B-29 Superfortress. Stillwater, Minnesota: Voyageur Press, 1999. ISBN 0-933424-79-5.

- Brown, J. "RCT Armament in the Boeing B-29". Air Enthusiast, Number Three, 1977, pp. 80–83.

- Campbell, Richard H., The Silverplate Bombers: A History and Registry of the Enola Gay and Other B-29s Configured to Carry Atomic Bombs. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005. ISBN 0-7864-2139-8.

- Chant, Christopher. Superprofile: B-29 Superfortress. Sparkford, Yeovil, Somerset, UK: Haynes Publishing Group, 1983. ISBN 0-85429-339-6.

- Craven, Wesley Frank and James Lea Cate, eds. The Army Air Forces In World War II: Volume Five: The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 to August 1945. Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, 1983.

- Davis, Larry. B-29 Superfortress in Action (Aircraft in Action 165). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89747-370-1.

- Dear, I.C.B. and M.R.D. Foo, eds. The Oxford Companion of World War II. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-866225-4.

- Dorr, Robert F. B-29 Superfortress Units in World War Two. Combat Aircraft 33. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2002. ISBN 1-84176-285-7.

- Dorr, Robert F. B-29 Superfortress Units of the Korean War. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84176-654-2.

- Fopp, Michael A. The Washington File. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians) Ltd., 1983. ISBN 0-85130-106-1.

- Francillon, René J. McDonnell Douglas Aircraft since 1920. London: Putnam, 1979. ISBN 0-370-00050-1.

- Futrell R.F. et al. Aces and Aerial Victories: The United States Air Force in Southeast Asia, 1965–1973. Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, 1976. ISBN 0-89875-884-X.

- Grant, R.G. and John R. Dailey. Flight: 100 Years of Aviation. Harlow, Essex, UK: DK Adult, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7566-1902-2.

- Herbert, Kevin B. Maximum Effort: The B-29s Against Japan. Manhattan, Kansas: Sunflower University Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0-89745-036-2.

- Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II. New York: Random House, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- Hess, William N. Great American Bombers of WW II. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1999. ISBN 0-7603-0650-8.

- Higham, Robin and Carol Williams, eds. Flying Combat Aircraft of USAAF-USAF. Volume 1. Washington, D.C.: Air Force Historical Foundation, 1975. ISBN 0-8138-0325-X.

- Howlett, Chris. "Washington Times". http://www.rafwatton.info/History/TheWashington/tabid/90/Default.aspx

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982–1985). London: Orbis Publishing, 1985.

- Johnsen, Frederick A. The B-29 Book. Tacoma, Washington: Bomber Books, 1978. ISBN 1-135-76473-5 |.

- Johnson, Robert E. "Why the Boeing B-29 Bomber, and Why the Wright R-3350 Engine?" American Aviation Historical Society Journal, 33(3), 1988, pp. 174–189. ISSN 0002-7553.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Post-World War II Bombers, 1945–1973. Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, 1988. ISBN 0-16-002260-6.

- LeMay, Curtis and Bill Yenne. Super Fortress. London: Berkley Books, 1988. ISBN 0-425-11880-0.

- Lewis, Peter M. H., ed. "B-29 Superfortress". Academic American Encyclopedia. Volume 10. Chicago: Grolier Incorporated, 1994. ISBN 978-0-7172-2053-3.

- Lloyd, Alwyn T. B-29 Superfortress, Part 1. Production Versions (Detail & Scale 10). Fallbrook, California/London: Aero Publishers/Arms & Armour Press, Ltd., 1983. ISBN 0-8168-5019-4 (USA). ISBN 0-85368-527-4 (UK).

- Lloyd, Alwyn T. B-29 Superfortress. Part 2. Derivatives (Detail & Scale 25). Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania/London: TAB Books/Arms & Armour Press, Ltd., 1987. ISBN 0-8306-8035-7 (USA). ISBN 0-85368-839-7 (UK).

- Mann, Robert A. The B-29 Superfortress: A Comprehensive Registry of the Planes and Their Missions. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2004. ISBN 0-7864-1787-0.

- Mann, Robert A. The B-29 Superfortress Chronology, 1934-1960. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009. ISBN 0-7864-4274-3.

- Marshall, Chester. Warbird History: B-29 Superfortress. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1993. ISBN 0-87938-785-8.

- Mayborn, Mitch. The Boeing B-29 Superfortress (Aircraft in Profile 101). Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1971 (reprint).

- Nowicki, Jacek. B-29 Superfortress (Monografie Lotnicze 13) (in Polish). Gdańsk, Poland: AJ-Press, 1994. ISBN 83-86208-09-0.

- Pace, Steve. Boeing B-29 Superfortress. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, United Kingdom: Crowood Press, 2003. ISBN 1-86126-581-6.

- Peacock, Lindsay. "Boeing B-29... First of the Superbombers, Part One." Air International, August 1989, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 68–76, 87. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Peacock, Lindsay. "Boeing B-29... First of the Superbombers, Part Two." Air International, September 1989, Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 141–144, 150–151. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Pimlott, John. B-29 Superfortress. London: Bison Books Ltd., 1980. ISBN 0-89009-319-9.

- Rigmant, Vladimir. B-29, Tу-4 – стратегические близнецы – как это было (Авиация и космонавтика 17 [Крылья 4] (in Russian). Moscow: 1996.

- Vander Meulen, Jacob. Building the B-29. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 1995. ISBN 1-56098-609-3.

- Wegg, John. General Dynamics Aircraft and their Predecessors. London: Putnam, 1990. ISBN 0-85177-833-X.

- Wheeler, Barry C. The Hamlyn Guide to Military Aircraft Markings. London: Chancellor Press, 1992. ISBN 1-85152-582-3.

- Wheeler, Keith. Bombers over Japan. Virginia Beach, Virginia: Time-Life Books, 1982. ISBN 0-8094-3429-6.

- White, Jerry. Combat Crew and Unit Training in the AAF 1939–1945. USAF Historical Study No. 61. Washington, D.C.: Center for Air Force History, 1949.

- Williams, Anthony G. and Emmanuel Gustin. Flying Guns World War II: Development of Aircraft Guns, Ammunition and Installations 1933–45. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife, 2003. ISBN 1-84037-227-3.

- Willis, David. "Boeing B-29 and B-50 Superfortress". International Air Power Review, Volume 22, 2007, pp. 136–169. Westport, Connecticut: AIRtime Publishing. ISSN 1473-9917. ISBN 1-880588-79-X.

- Wolf, William. Boeing B-29 Superfortress: The Ultimate Look. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-7643-2257-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to B-29 Superfortress. |

- B-29 Combat Crew Manual

- "Meet the B-29", Popular Science, August 1944—the first large and detailed public article printed on the B-29 in the USA

- National Museum B-29 Superfortress Official Fact Sheet Retrieved: 11 August 2007.

- 330th BG, 330th, 20th AF, 314th BW, 330th Bomb Group official history and first-hand accounts

- 315th BW at Guam, 20th AF, photographs, history, first-hand accounts, reunion information

- B-29 "DOC" Restoration Project, the restoration of Doc

- Bombers Over Japan, development, photos, and history

- Pelican's Perch #56:Superfortress!, Article wrote by John Deakin, one of the pilots who regularly fly the world's only remaining flyable B-29

- WarbirdsRegistry.org B-29/B-50, Listing of surviving B-29s

- Annotated bibliography on the B-29 from the Alsos Digital Library

- "Great Engines and Great Planes", 1947 – 130 page book about the rapid design, testing, and production of the B-29 powerplant by Chrysler Corporation in World War II

- T-Square-54: The Last B-29 website, by Tom Mathewson

- B-29 Flight Procedure and Combat Crew Functioning - 1944 US Army Air Forces Training Film on YouTube

- B-29 & B-50 production batches and serial numbers

- Washington Times

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||