Bodo League massacre

| Bodo League massacre | |

|---|---|

Summary execution of South Korean political prisoners by the South Korean military and police at Daejeon, South Korea | |

| Location | Korea |

| Date | summer of 1950 |

| Target | Communist sympathizers |

Attack type | Massacre |

| Deaths | At least 100,000[1] |

| Perpetrators | Syngman Rhee anticommunist forces |

| Motive | Anti-communism; fear of North Korean collaborators |

The Bodo League massacre (Hangul: 보도연맹 사건; hanja: 保導聯盟事件) was a massacre and war crime against communists and suspected sympathizers (many of whom were civilians who had no connection with communism or communists) that occurred in the summer of 1950 during the Korean War. Estimates of the death toll vary. According to Prof. Kim Dong-Choon, Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, at least 100,000 people were executed on suspicion of supporting communism;[2] others estimate 200,000[3] and even 1.2 million deaths.[4] The massacre was wrongly blamed on the communists.[5] For four decades the South Korean government concealed this massacre. Survivors were forbidden by the government from revealing it, under suspicion of being communist sympathizers. Public revelation carried with it the threat of torture and death. During the 1990s, several corpses were excavated from mass graves, resulting in public awareness of the massacre.[6]

Bodo League

In June 1949, the South Korean government accused independence activists of being members of the Bodo League, and subsequently arrested them.[7]

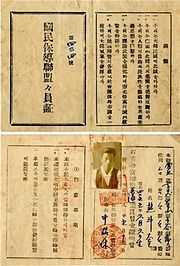

In 1950, just before the outbreak of the Korean War, the first president of South Korea, Syngman Rhee, had about 30,000 alleged communists imprisoned. He also had about 300,000 suspected sympathizers or his political opponents enrolled in an official "re-education" movement known as the Bodo League (or National Rehabilitation and Guidance League, National Guard Alliance,[7] National Guidance Alliance[8] National Bodo League,[9] Bodo Yeonmaeng,[7] Gukmin Bodo Ryeonmaeng, 국민보도연맹, 國民保導聯盟) on the pretext of protecting them from execution.[5][7][10] The League had been created by Korean jurists who had collaborated with the Japanese.[3] Many Bodo League members were civilians; as most leftists had already been purged or had fled to North Korea, and the local police had enrollment quota to fill, up to 70 percent of the members were non-political.[3] Non-communist sympathizers or political opponents of Rhee were also forced into the Bodo League to fill enlistment quotas.[9][10]

Executions

Under the leadership of Kim Il-sung, the Korean People's Army attacked from the North on 25 June 1950, starting the Korean War.[12] According to Kim Mansik, who was a military police superior officer, President Syngman Rhee ordered the execution of people related to either the Bodo League or the South Korean Workers Party on 27 June 1950.[13][14] The first massacre was started one day later in Hoengseong, Gangwon-do on 28 June.[14][15] Retreating South Korean forces and anti-communist groups[16] executed the alleged communist prisoners, along with many of the Bodo League members.[5] The executions were performed without any trials or sentencing.[17]

United States official documents show American officers witnessed and photographed the massacre.[17] In one case a US officer is known to have sanctioned the killing of political prisoners so that they would not fall into enemy hands.[5][18] On the other hand, United States official documents show that John J. Muccio, then United States Ambassador to South Korea, made recommendations to South Korean President Rhee Syngman and Defense Minister Shin Sung-mo that the executions be stopped.[17] American witnesses also reported the scene of the execution of a girl who appeared to be 12 or 13 years old.[8][17] The massacre was also reported to both Washington and General Douglas MacArthur,[5] who described them as an "internal matter".[3] [19] According to one witness, forty victims had their backs broken with rifle butts and were shot later. In many seaside villages, victims were tied together and thrown into the sea to drown.[20]

There were also British and Australian witnesses.[5][21] Great Britain raised this issue with the U.S. at a diplomatic level, causing Dean Rusk, Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs, to inform the British that U.S. commanders were doing "everything they can to curb such atrocities".[8] During the massacre, the British protected their allies and saved some citizens.[22][23] In the autumn of 1951, the British seized “Execution Hill” in occupied North Korea to prevent more mass killings.[3]

Retired South Korean Admiral Nam Sang-hui confessed that he authorized 200 victims' bodies to be thrown into the sea, saying: "There was no time for trials for them."[17]

Aftermath

After the UN offensive in which South Korea recovered its occupied territories, the police and militia groups executed people who were suspected as North Korean sympathizers. In October 1950, the Goyang Geumjeong Cave Massacre occurred. In December British troops saved civilians lined up to be shot by South Korean officers and seized one execution site outside Seoul to prevent further massacres.[8][22] In 1951 the Ganghwa massacre were conducted by South Korean police.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

In 2008, trenches containing the bodies of children were discovered in Daejeon, South Korea, and other sites.[18][11] South Korea's Truth and Reconciliation Commission documented testimonies of those still alive and who took part in the executions, including former Daejeon prison guard Lee Joon-young.

Besides photographs of the execution trench sites, the National Archives in Washington D.C. released declassified photographs of U.S. soldiers at execution sites including Daejeon, confirming American military knowledge.[18]

Additional photographs

See also

References

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the Korean War, Paul M. Edwards, Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press, 2010, p. 32, entry "Bodo League Massacre"

- ↑ "Khiem and Kim Sung-soo: Crime, Concealment and South Korea". Japan Focus. Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 John Tirman (2011). The Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America's Wars. Oxford University Press. p. 97.

- ↑ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2013). Atrocities, Massacres, and War Crimes: An Encyclopedia [2 Volumes]: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 755. ISBN 9781598849264.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 "South Korea owns up to brutal past". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- ↑ http://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=055&aid=0000171996

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Family tragedy indicative of S. Korea’s remaining war wounds – Kim Gwang-ho is waiting for the government to apologize for state crimes committed against his father and grandfather". Hankyoreh. 23 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Writers Charles J. Hanley and Jae-Soon Chang (11 February 2009). "U.S. Allowed Korean Massacre In 1950". Associated Press (CBS). Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Waiting for the truth – A missed deadline contributes to a lost history". Hankyoreh. 25 June 2007. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bae Ji-sook (3 February 2009). "Gov’t Killed 3,400 Civilians During War". Korea Times. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Charles J. Hanley & Hyung-Jin Kim (10 July 2010). "Korea bloodbath probe ends; US escapes much blame". Associated Press (San Diego Union Tribune). Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Stokesbury, James L (1990). A Short History of the Korean War. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-688-09513-5.

- ↑ 60년 만에 만나는 한국의 신들러들. Hankyoreh (in Korean). 25 June 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "보도연맹 학살은 이승만 특명에 의한 것" 민간인 처형 집행했던 헌병대 간부 최초증언 출처 : "보도연맹 학살은 이승만 특명에 의한 것" – 오마이뉴스. Ohmynews (in Korean). 4 July 2007. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ 헌병대의 보도연맹원 '대량학살' 최초 구체증언 확보 6.25 당시 헌병대 과장 김만식 씨 증언 토대, 전국 조직적 학살 자행. CBS (in Korean). 4 July 2007. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ Kim Young Sik (17 November 2003). "The left-right confrontation in Korea – Its origin". asianresearch.org. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 "New evidence of Korean war killings". BBC. 21 April 2000. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Charles J. Hanley and Jae-soon Chang (7 December 2008). "Children 'executed' in 1950 South Korean killings". Associated Press (Fox News). Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ↑ Paul M. Edwards (2010). Historical Dictionary of the Korean War. Scarecrow Press Inc. p. 33.

- ↑ John Tirman (2011). The Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America's Wars. Oxford University Press. p. 97.

- ↑ "Truth commission confirms Korean War killings by soldiers and police 3,400 civilians and inmates were shot dead or drowned out of concerns they might cooperate with the People’s Army". Hankyoreh. 3 March 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Unearthing proof of Korea killings". BBC. 18 August 2008. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ↑ Writers Charles J. Hanley and Jae-Soon Chang (11 February 2009). "AP: U.S. Allowed Korean Massacre In 1950". CBS News (AP). Retrieved 4 June 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bodo League massacre. |

- Mass Killings in Korea — Commission Probes Hidden History of 1950, Associated Press (Video and Documents)

- Unearthing War’s Horrors Years Later in South Korea, New York Times, 3 December 2007.

- TRCK confirms hundreds of villagers were massacred during onset of Korean War The commission advises an official state apology and will continue investigations of the National Guard Alliance through the end of the year, Hankyoreh, 17 November 2009.

- Truth commission confirms Korean War killings by soldiers and police 3,400 civilians and inmates were shot dead or drowned out of concerns they might cooperate with the People’s Army, Hankyoreh, 3 March 2009.