Bodélé Depression

Coordinates: 16°57′22.4″N 17°46′51.2″E / 16.956222°N 17.780889°E

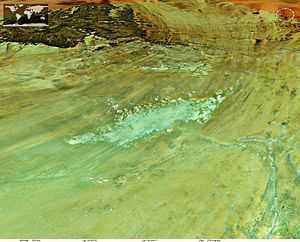

The Bodélé Depression (also Bodele), located at the southern edge of the Sahara Desert in north central Africa, is the lowest point in Chad. Dust storms from the Bodélé Depression occur on average about 100 days per year,[1] one typical example being the massive dust storms that swept over West Africa and the Cape Verde Islands in February 2004.[2][3] As the wind sweeps between the Tibesti and the Ennedi Mountains in Northern Chad, it is channeled across the depression. The dry bowl that forms the depression is marked by a series of ephemeral lakes, many of which were last filled during wetter periods of the Holocene.

Diatoms from these fresh water lakes, once part of Mega-Lake Chad, now make up the surface of the depression and are the source material for the dust,[1] which, carried across the Atlantic Ocean, is an important source of nutrient minerals for the Amazon rainforest.

Drying up of Lake Chad

As the Sahara dried out over the last few thousand years, Mega-Lake Chad receded to the current position of Lake Chad in the south-west corner of Chad. In the mid-1960s, Lake Chad was about the size of Lake Erie. But persistent drought conditions associated with the great Sahel drought coupled with increased demand for fresh water for irrigation have reduced Lake Chad to about 5 percent of its former size. As the waters receded, the silts and sediments resting on the lakebed were left to dry in the scorching African sun. The small grains of the diatomite are swept up by the strong wind gusts that occasionally blow over the region. Once heaved aloft, the Bodélé dust can be carried for hundreds or even thousands of kilometers.[2] In winter, the depression produces an average of 700,000 tonnes of dust each day (Todd et al., 2007).[4]

Research published in the 25 March 2004 edition of Geophysical Research Letters, which used images taken by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), aboard NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites, indicated that storms move across the Bodélé Depression at about 47 km/h (29 mi/h)—two times faster than previously believed. The research also found that winds have to whip across the region at a minimum of 36 km/h (22 mi/h), to kick up a dust storm.[1][5] The pattern of air flow is so common that the winds have scoured a straight path in the ground, marking its southwesterly flow.[2]

Complementary research published in Geophysical Research Letters by Richard Washington from the University of Oxford and Martin Todd (University of Sussex) has shown that these strong winds are part of feature now called the Bodele Low Level Jet. In the Reanalysis data sets such as ERA-40 the wind shows up as a clear wind speed maximum at about 900 hPa (or roughly 1 km above the surface) near 18 N and 19 E. This jet maximum coincides with the exit gap of the North-easterlies between the Tibesti mountains and the Ennedi massif which lie 2600 m and 1000 m above the flat terrain in the Djourab Desert of Chad respectively. The effect of the Tibesti massif is clearly evident in creating a split in the low-level easterly flow north and south of these mountains. While the jet feature is pronounced over the Bodele, it is absent from other longitudes over west Africa along 18 N. It is therefore a feature which uniquely overlies the greater Bodele region, downwind of the mountains of Chad.[6]

The Bodele Low Level Jet undergoes a marked seasonal cycle. It is active in the October–March period and relatively inactive from June–August. This timing closely matches the seasonality of dust emission from the Bodele. Individual dust storms in the Bodele were also shown in this research to coincide with a major strengthening of the Bodele Low Level Jet which, in turn, is associated with the ridging of the Libyan High, a feature of the subtropical High Pressure belt.[1][6]

The same researchers who in 2004 more accurately determined the speed of wind through the depression also published in 2006 work showing that more than half of the dust needed for fertilizing the Amazon Rainforest is provided by the Bodélé depression, depositing up to 50 million tonnes in South America per year.[7][8][9] The research also shows that, contrary to what was previously thought, most of the Saharan dust that reaches the east coast of the United States originates from a single source—the Bodele depression.[10]

The Bodele Dust Experiment

In February 2005 the first field experiment, the Bodele Dust Experiment or BoDEx 2005, was carried out in the Bodele Depression. The experiment measured the surface winds and near surface winds, dust concentrations and the influence of dust on the radiation budget in the Bodele Depression for the first time.[1] This work coincided with a major dust emission event during which the Bodele Low Level Jet sustained surface wind speeds of around 16 m/s. The core of the Bodele Low Level Jet was also mapped for the first time from the wind data and was shown to undergo a very marked diurnal cycle with peak winds occurring mid morning. During night time, the Bodele Low Level Jet flows over a near-surface inversion but quickly mixes down to the surface a few hours after sunrise once the intense surface heating induces turbulence in the lowest layers.

Dust from the Bodele may be seen as a simple coincidence of two key requirements for deflation: strong surface winds and erodible sediment. But recent research has argued that long-term links exist between topography, wind, deflation and dust and that topography acts as the controlling agent ensuring the long term maintenance of this source. The spatial co-location of strong winds and dust is not simply fortuitous but results from a set of processes. Specifically:

- Contemporary deflation from the Bodele is delineated by topography such that wind stress, the maximum in dust output and the topographic depression are colocated.

- The topography of the Tibesti and Ennedi Mountains plays a key role in the generation of the Bodele Low Level Jet.

- Enhanced deflation from a stronger Bodele Low Level Jet during drier phases, such as the Last Glacial Maximum was probably sufficient to create or enhance a shallow lake populated by diatoms during wetter phases, such as the Holocene pluvial.

Wind conditions which deflate the erodible sediment now may have created the depression necessary for generating the erodible diatomite in the past. Instead of a simple coincidence of nature, the world’s largest source results from a system of processes operating over paleo timescales.[11]

The largest town associated with the Bodele dust source is Faya-Largeau (17°55′00″N 19°7′00″E / 17.91667°N 19.11667°E), located just to the north of the depression.[12]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Washington R, et al. Dust and the Low Level Circulation over the Bodélé Depression, Chad: Observations from BoDEx 2005, J. Geophys. Res.Atmospheres Vol. 111, No. D3, D03201.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Dust Storms from Africa's Bodélé Depression". Natural Hazards, Earth Observatory, NASA. URL accessed 2006-12-29.

- ↑ "Dust in the Bodélé Depression". Natural Hazards, Earth Observatory, NASA. URL accessed 2006-12-29.

- ↑ Fisher, Richard. "Amazon forest relies on dust from one Saharan valley". NewScientist Environment online. 3 Jan 2007. URL accessed 2007-01-04.

- ↑ Koren, Ilan; Yoram J. Kaufman (2004). "Direct wind measurements of Saharan dust events from Terra and Aqua satellites". Geophysical Research Letters (American Geophysical Union) 31 (6). Bibcode:2004GeoRL..3106122K. doi:10.1029/2003GL019338. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Washington R., and Todd M.C., Atmospheric Controls on Mineral Dust Emission from the Bodélé Depression, Chad: The role of the Low Level Jet, Geophysical Research Letters 32 (17): Art. No. L17701, 2005.

- ↑ "Dust to gust". EurekAlert!. AAAS. 28 Dec 2006. URL accessed 2006-12-29.

- ↑ Koren, Ilan et al. (2006). "The Bodélé depression: a single spot in the Sahara that provides most of the mineral dust to the Amazon forest (abstract)". Environmental Research Letters (Institute of Physics and IOP Publishing Limited) 1 (1): 014005. Bibcode:2006ERL.....1a4005K. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/1/1/014005. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- ↑ Ben-Ami, Y. et al. (February 12, 2010). "Transport of Saharan dust from the Bodélé Depression to the Amazon Basin: a case study". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (European Geosciences Union) 10 (2): 4345–4372. doi:10.5194/acpd-10-4345-2010. Retrieved November 2013.

- ↑ "New Earth Science Journal Highlights the Work of Climate and Radiation Branch Scientists". Climate News. NASA GSFC. 1 Nov 2006. URL accessed 2006-12-29.

- ↑ R. Washington, M. C. Todd, G. Lizcano, I. Tegen, C. Flamant, I. Koren, P. Ginoux, S. Engelstaedter, A. S. Goudie, C. S. Zender, C. Bristow and J. Prospero, Links between topography, wind, deflation, lakes and dust: The case of the Bodélé depression, Chad, Geophysical Research Letters Vol. 33, L09401, doi:10.1029/2006GL025827, 2006.

- ↑ Prospero, Joseph M et al. "Environmental Characterization of Global Sources of Atmospheric Soil Dust Identified with the Nimbus 7 Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (Toms) Absorbing Aerosol Product". Reviews of Geophysics. 40(1). Feb 2002.

Scientific American Feb 2012 Swept from Africa to the Amazon

It has been shown that Saharan soil may have the potential of producing bioavailable iron when illuminated with visible light and also it has some essential macro and micro nutrient elements. In this study the impact of various growth media on development of some bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and durum wheat (Triticum durum L.) cultivars have been investigated. As a four different nutrient media, Hewitt nutrient solution [1], illuminated and non-illuminated Saharan desert soil solutions and distilled water have been utilized. Shoot length (cm.seedling-1), leaf area (cm2 seedling-1) and photosynthetic pigments [chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and carotenoids, mg ml-1 g fresh weight (g fw)-1] have been determined. The results of this study indicate that, wheat varieties fed by irradiated Saharan soil solution gave comparable results to Hewitt nutrient solution (Yücekutlu et al., 2011).

Yücekutlu A.N., Terzioğlu S., Saydam C. and Bildacı I., (2011. Organic Farming By Using Saharan. Soil: Could It Be An Alternative To Fertilizers? Hacettepe J. Biol. & Chem., 2011, 39 (1), 29–37.