Board of Fortifications

Several boards have been appointed by US presidents or Congress to evaluate the US defensive fortifications, primarily coastal defenses near strategically important harbors on the US shores, its territories, and its protectorates.

Endicott Board

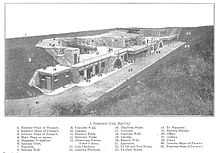

In 1885 US President Grover Cleveland appointed a joint Army, Navy and civilian board, headed by Secretary of War William Crowninshield Endicott, known as the Board of Fortifications (now usually referred to simply as the Endicott Board). The findings of the Board in its 1886 report[1] illustrated a grim picture of neglect of America's coast defenses and recommended a massive $127 million construction program for a series of new forts with breech-loading cannons, mortars, floating batteries, and submarine mines for some 29 locations on the US coast. Coast Artillery fortifications built between 1885 and 1905 are often referred to as Endicott Period fortifications.

Prior efforts at harbor defense construction had ceased in the 1870s. Since that time the design and construction of heavy ordnance had advanced rapidly, including the development of superior breech-loading and longer-range cannon, making U.S. harbor defenses obsolete. In 1883, the Navy had begun a new construction program with an emphasis on offensive rather than defensive warships, and many foreign powers were building more heavily armored warships with larger guns. These factors combined to create a need for improved coastal defense systems.

The Endicott Era Defenses were constructed, in large part, during the years of 1890-1910 and some remained in use until 1945. Endicott Era Forts ushered the transition from mortar to concrete as a building material in response to the massive technological discoveries in arms and ordinance brought on by the American Civil War. Masonry walls shrouding hordes of smooth-bore cannon could no longer serve as a primary coastal defense mechanism, thus the Endicott Era Defenses were born.

Endicott Era Forts were constructed with concrete walls that concealed large, breech-loading rifled cannons mounted on "disappearing carriages". These disappearing carriages allowed the new, rifled cannons to be raised above the walls, aimed, and fired, and then quickly and easily move back underneath the walls, becoming invisible from the sea. the fact that these cannons were "breech loading" is also not to be overlooked a significant technological advancement, as it allowed for a much more rapid, accurate, and safe manipulation of artillery by its crew. This became even more important as Warships of the Era (such as the Spanish warship "Pelayo") were armored with steel plates, increasing the necessity of accurate, sustained fire in anti-ship warfare. For reference, the Model 1873 Springfield (in service with the United States Army from 1873-1892 with some use in the Spanish-American War) was the first breech-loading rifle adopted as standard-issue by the United States Army. These larger guns were complemented by a variety of other ordinance best explained by describing the armament of Fort Hancock, one of the vanguards of New York's Southern Harbor, part of which was the prototype by which all other Endicott Era Forts were constructed.

Fort Hancock's Endicott Era Defenses:

Dynamite Gun Battery: (3) 15" dynamite guns and (1) 8" dynamite gun

Battery Potter: (2) 12" disappearing guns. (This and the Mortar Battery were the first prototype concrete gun batteries of the Endicott System)

Battery Granger: (2) 10" counterweight disappearing guns

Nine-Gun Battery Consisted of Batteries: Alexander: (2) 12" counterweight disappearing guns Richardson: (2) 12" counterweight disappearing guns Bloomfield: (2) 12" counterweight disappearing guns Halleck: (3) 10" counterweight disappearing guns

Mortar Battery Consisted of Batteries: McCook: (8) 12" Mortars Reynolds: (8) 12" Mortars

Fort Hancock was also equipped with several batteries of rapid fire guns, tasked with protecting the underwater minefields from smaller, swifter-moving vehicles.The rapid-fire gun batteries were:

Battery Engle: (1) 5" gun on pedestal mounts

Battery Morris: (4) 3" guns on pedestal mounts

Battery Urmston: (4) 15-pounders and (2) 3" guns on pedestal mounts

Battery Peck: (2) 6" guns on pedestal mounts

Battery Gunnison: (2) 6" counterweight disappearing guns

In addition to submarine nets and searchlights, Fort Hancock, and other Forts of the Endicott System, also had a hidden, unseen weapon that harnessed the newfound power of the modern age: Underwater controlled minefield system that utilized a mine casemate on Sandy Hook from where underwater mines could be detonated at will via electrical cables to destroy warships. This marked the first instance of concrete and electricity being used together in defenses.

An easily overlooked aspect of the Endicott Era Defenses, especially with the necessary highlighting of the breech-loading rifled artillery mounted on disappearing carriages, are the mortars. At Fort Hancock, Battery Potter's (2) 12" guns mounted on disappearing carriages and the Mortar Battery, together formed the model for other Endicott Era Forts. The reason is because the mortars were: 1) voluminous 2) before the establishment of the Coast Artillery Corps in 1907 (see below) they operated in the Abbot-Quad design, which very nicely complemented the capabilities of the larger, rifled guns. The Abbot-Quad design called for mortars to be fired in 4-16 gun salvos, in shotgun-like patterns designed to overcome the shortcomings of range-finding techniques of the time. This mode of fire resulted in clusters of mortar fire raining from above, with a much steeper arch than other artillery shells, which rained ½ ton mortar shells down onto the often poorly armored decks of enemy ships, which served to incite panic as well as material destruction. Perhaps most important to note, of the Endicott Era Defenses armaments, the mortars exceeded all but the 12" M1888 (disappearing carriage) guns in range and, while pursuant to the Abbot-Quad design they were not intended to operate as such, they did have a 360 degree field of fire providing a great versatility in their application.[2]

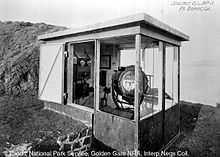

In 1907 the Coast Artillery Corps was created which vastly increased garrisons, as well as catalyzed the installation of electrical plants at various Forts, meteorological stations became standard at every post, and telephone communications were added. All of this served as the capstone of the Endicott Era Defenses, soon to be furthered by the actions of the Taft Era.

Taft Board

In 1905, after the experiences of the Spanish–American War, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed a new board, under secretary of war William Howard Taft. They updated some standards and reviewed the progress on the Endicott Board's program. Most of the changes recommended by the Taft Board were technical, such as adding more searchlights, electrification (lighting, communications, and projectile handling), and more sophisticated optical aiming techniques.[3] The Board also recommended fortifications in territories acquired from Spain (Cuba and the Philippines), as well as Hawaii, and a few other sites. Defenses in Panama were authorized by the Spooner Act of 1902. The Taft program fortifications differed slightly in battery construction and had fewer guns at a given location than those of the Endicott program.

World War I and later

By the time of the First World War, many of the Endicott and Taft era forts had become obsolete due to the increased range and accuracy of naval weaponry and the advent of aircraft. In the 1920s and 1930s, most U.S. coast defense facilities were put on "maintenance" status, a type of "mothballing." In the late 1930s and early 1940s, a new program of construction added huge 16-inch gun batteries, as well as rapid-firing 6-inch and 90 mm guns (for use against motor torpedo boats) to many harbors' defenses, and large fields of submarine mines were still being deployed as well. But as it became clearer that the U.S. was unlikely to face seaborne attack, these defenses were largely discontinued (by 1945), and were decommissioned altogether after 1946.

Endicott-Taft forts at war

The only Endicott era fort to come under direct enemy fire was Fort Stevens at the mouth of Columbia River in Oregon. On the night of June 20, 1942, the Japanese submarine I-25 surfaced off the coast and proceeded to shell Fort Stevens in the vicinity of Battery Russell. There were no U.S. casualties and damage to the fort was negligible. The battery commander made the decision not to return fire.

Several Taft era fortifications in the Philippines were attacked and captured by Imperial Japanese forces within a few months of the U.S. entry into World War II. Fort Mills, Fort Hughes, Fort Drum (El Fraile Island), and Fort Frank guarding the entrance to Manila Bay were subjected to a three-month siege that ended when U.S. forces surrendered on May 6, 1942. All four forts were recaptured by U.S. forces in early 1945. At no point was any of the Taft era weaponry used against the targets for which they were designed, namely armored ships.

Preserved forts and surviving weaponry

Several Endicott-Taft era forts have been preserved in the United States, though most of the period weaponry was dismantled and scrapped in the 1940s and 1950s. Fort Casey and Fort Worden on the Puget Sound in Washington State are now state parks, their extensive concrete gun emplacements, as well as many supporting structures, have been preserved and are now open to the public. Fort Winfield Scott at the Presidio in San Francisco contains several Endicott-Taft era emplacements in various states of preservation. Fort Winfield Scott is part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Only a few examples of Endicott-Taft era weaponry survive to this day in the United States.

- Battery Worth at Fort Casey contains two 10-inch M1895MI guns on disappearing carriages that were salvaged from Fort Wint in the Philippines in the 1960s.

- Battery Laidley at Fort De Soto just outside the city of St. Petersburg, Florida still possesses four 12-inch M1890-M1 mortars that were originally mounted in 1902.

- Battery Cooper at Fort Pickens near Pensacola, Florida contains one 6-inch M1905 gun on a disappearing carriage.

- Battery Chamberlain at Fort Scott in San Francisco contains one 6-inch M1905 gun on a disappearing carriage.

- Battery Peck (formerly Battery Gunnison) at Fort Hancock, New Jersey contains one 6-inch M1900 gun on a pedestal mount.

See also

- Seacoast defense in the United States

- List of coastal fortifications of the United States of America

Table of guns by caliber and carriage types

The following is summarized from American Seacoast Defenses, edited by Mark Berhow, with pages referenced from the rows.[4] The units column reflects the lower of the original emplacements or the carriages built, since some emplacements were not armed and some carriages not used. Carriage models after 1905 are not included in the Endicott Era table.

| Model | Carriage | Tube | Caliber | Units | Page |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1901 | disappearing | rifle | 12 inch | 13 | 150 |

| M1897 | disappearing | rifle | 12 inch | 35 | 148 |

| M1897 | Altered | rifle | 12 inch | 3 | 146 |

| M1896 | Mortar | Mortar | 12 inch | 308 | 140 |

| M1896 | disappearing | rifle | 12 inch | 27 | 138 |

| M1892 | disappearing | rifle | 12 inch | 28 | 136 |

| M1891 | Mortar | Mortar | 12 inch | 86 | 134 |

| M1888 | lift | rifle | 12 inch | 2 | 130 |

| M1901 | disappearing | rifle | 10 inch | 16 | 128 |

| M1896 | disappearing ARF | rifle | 10 inch | 3 | 126 |

| M1896 | disappearing | rifle | 10 inch | 74 | 124 |

| M1894 | disappearing | rifle | 10 inch | 35 | 122 |

| M1893 | barbette | rifle | 10 inch | 9 | 120 |

| M1896 | disappearing | rifle | 8 inch | 38 | 110 |

| M1894 | disappearing | rifle | 8 inch | 26 | 108 |

| M1892 | barbette | rifle | 8 inch | 9 | 106 |

| M1905 | disappearing | rifle | 6 inch | 33 | 100 |

| M1903 | disappearing | rifle | 6 inch | 90 | 98 |

| M1900 | pedestal | rifle | 6 inch | 44 | 96 |

| M1898 | disappearing | rifle | 6 inch | 29 | 94 |

| Armstrong | pedestal | rifle | 6 inch | 8 | 92 |

| M1903 | pedestal | rifle | 5 inch | 20 | 90 |

| M1896 | pilar | rifle | 5 inch | 32 | 88 |

| Armstrong | pedestal | rifle | 4.72 inch | 34 | 86 |

| Army/Navy | pedestal | rifle | 4 inch | 4 | 84 |

| M1903 | pedestal | rifle | 3 inch | 101 | 74 |

| M1902 | pedestal | rifle | 3 inch | 60 | 72 |

| M1898 | parapet | rifle | 3 inch | 111 | 70 |

Notes

- ↑ Endicott, William C., "Report of the Board on Fortifications or Other Defenses Appointed by the President of the United States," in U.S. House of Representatives Ex. Doc No. 49, 49th Congress, 1st Session, Government Printing Office, Washington [D.C.], 1886. Reprinted for the Coast Defense Study Group by Thomson-Shore, Inc., Dexter, MI, 2007.

- ↑ "Endicott Era Defenses". www.nps.gov.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ McGovern, p. 28

- ↑ Berhow, Mark A., Ed. (2004). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide, Second Edition. CDSG Press. ISBN 0-9748167-0-1.

References

- Berhow, Mark A., Ed. (2004). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide, Second Edition. CDSG Press. ISBN 0-9748167-0-1.

- Kaufmann, J.E.; Kaufmann, H.W. (2004). Fortress America: The Forts That Defended America, 1600 to the Present. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81550-8.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1993). Seacoast Fortifications of The United States: An Introductory History. Annapolis: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-502-6.

- McGovern, Terrance; Smith, Bolling (2006). American Coastal Defences 1885-1950. Osprey. ISBN 1-8417692-2-3.

- Harbor Defenses of San Francisco US Park Service

- United States Seacoast Defense Construction 1781-1948: a Brief History Coast Defense Study Group website