Bloody April

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bloody April refers to April 1917, and is the name given to the (largely successful) British air support operations during the Battle of Arras,[2] during which particularly heavy casualties were suffered by the Royal Flying Corps at the hands of the German Luftstreitkräfte.

The tactical, technological and training differences between the two sides ensured the British suffered a casualty rate nearly four times as great as their opponents. The losses were so disastrous that it threatened to undermine the morale of entire squadrons.[3] Nevertheless, the RFC contributed to the success, limited as it finally proved, of the British Army during the five-week campaign.

Background

In April 1917 the British Army began an offensive at Arras, planned in conjunction with the French High Command, who were simultaneously embarking on a massive attack (the Nivelle Offensive) about eighty kilometres to the south. The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) supported British operations by offering close air support, aerial reconnaissance and strategic bombing of German targets. The RFC's commanding officer, Hugh Trenchard believed in the offensive use of air power and pushed for operations over German-controlled territory. It was expected the large numbers of aircraft assembled over the frontlines in the spring of 1917 would fulfil this purpose. However, the aircraft were, for the most part, inferior to German fighter aircraft.

Crucially, British pilot training was not only poorly organised and inconsistent, it had to be drastically abbreviated in order to keep squadrons suffering heavy casualties up to strength. This was self-perpetuating, as it resulted in most new pilots lacking sufficient practical flight experience before reaching the war zone.

"...the worst carnage was amongst the new pilots – many of whom lasted just a day or two..."[4][5]

German pilot training was, at that time, more thorough and less hurried than the British programmes. After the heavy losses and failures against the French over Verdun in 1916, and against the British at the Somme they had reorganised their air forces into the Luftstreitkräfte by October 1916, which now included specialised fighter units.[6] These units were led by highly experienced pilots, some of them survivors of the Fokker Scourge period.[7] and had been working up with the first mass-produced twin-gunned German fighters, the Albatros D.I and D.II, comprising a total of nearly 350 aircraft between the two types.

Paradoxically, the one sided nature of the casualty lists during "Bloody April" was partly a result of German numerical inferiority. The German air forces mostly confined themselves to operating over friendly territory, thus reducing the possibility of losing pilots to capture and increasing the amount of time they could stay in the air. Moreover, they could choose when and how to engage in combat.[8]

Battle

The Battle of Arras began on 9 April 1917. The Allies launched a joint ground offensive, with the British attacking near Arras in Artois, northern France, while the French offensive was launched on the Aisne.

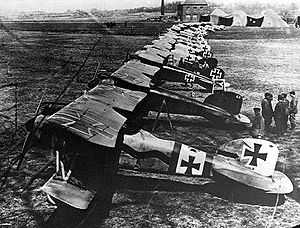

In support of the British army, the RFC deployed 25 squadrons, totalling 365 aircraft, about one-third of which were fighters (or "scouts" as they were called at the time). There were initially only five German Jastas (fighter squadrons) in the region, but this rose to eight as the battle progressed (some 80 or so operational fighter aircraft in total).

Since late 1916, the Germans had held the upper hand in the contest for air supremacy on the Western Front, with the twin-lMG 08 machine gun-armed Albatros D.II and D.III outclassing the fighters charged with protecting the vulnerable B.E.2c, F.E.2b and Sopwith 1½ Strutter two-seater reconnaissance and bomber machines. The allied fighter squadrons were equipped with obsolete "pushers" such as the Airco DH.2 and F.E.8 – and other outclassed types such as the Nieuport 17 and Sopwith Pup. Only the SPAD S.VII and Sopwith Triplane could compete on more or less equal terms with the Albatros; but these were few in number and spread along the front. The new generation of Allied fighters were not yet ready for service, although No. 56 Squadron RFC with the S.E.5 was working up to operational status in France. The Bristol F2A also made its debut with No. 48 Squadron during April, but lost heavily on its very first patrol, with four out of six shot down in an encounter with five Albatros D.IIIs of Jasta 11, led by Manfred von Richthofen. The new R.E.8 two-seaters, which were eventually to prove less vulnerable than the B.E.2e, also suffered heavy casualties in their early sorties.

During April 1917, the British lost 245 aircraft, 211 aircrew killed or missing and 108 as prisoners of war. The German Air Services recorded the loss of 66 aircraft during the same period. As a comparison, in the five months of the Battle of the Somme of 1916 the RFC had suffered 576 casualties. Under Richthofen's leadership, Jasta 11 scored 89 victories during April, over a third of the British losses.

In casualties suffered, the month marked the nadir of the RFC's fortunes. However, despite the losses inflicted, the German Air Service failed to stop the RFC carrying out its prime objectives. The RFC continued to support the army throughout the Arras offensive with up-to-date aerial photographs, reconnaissance information, effective contact patrolling during British advances and harassing bombing raids. In particular the artillery spotting aircraft rendered valuable reconnaissance to the British artillery, who were able to maintain their superiority throughout the battle. In spite of their ascendancy in air combat, the German fighter squadrons continued to be used defensively, flying for the most part behind their own lines. Thus the Jastas established "air superiority", but certainly not the air supremacy sometimes claimed.

Aftermath

Within a couple of months the new technologically advanced generation of fighter (the SE.5, Sopwith Camel, and SPAD S.XIII) had entered service in numbers and quickly gained ascendancy over the over-worked Jastas. As the British fighter squadrons became once more able to adequately protect the slower reconnaissance and artillery observation machines, RFC losses fell and German losses rose.

The RFC learned from their mistakes, instituting new policies on the improvement of training and tactical organisation. By mid-1917 better aircraft designs were reaching the front. By the late summer of 1917 the British achieved a greater measure of air superiority than they had held for almost a year. The casualties in the air campaigns through the remainder of the war were never so one sided again. In fact, this was essentially the last time that the Germans possessed real air superiority for the rest of the war — although the degree of allied dominance in the air certainly varied, the final all-out efforts of September 1918 causing even greater Allied losses.

See also

References

- ↑ Hart (2005) p. 11

- ↑ Hart (2005) pp. 11–13

- ↑ Hart (2005) pp. 326–327.

- ↑ Hart (2005) p. 11

- ↑ Bloody April: Slaughter in the Skies over Arras, 1917, (Preface) by Peter Hart. (Search for "amongst" in the search bar) Google Books. Retrieved 02 June 2014.

- ↑ Gray and Thetford (1962) pp.xxviii-xxx

- ↑ Mackersey (2012) pp.126–130

- ↑ Shores (1991) p.14

Bibliography

- Franks, Norman; Guest, Russell; Bailey, Frank W. (1995). Bloody April ... Black September. London: Grub Street. ISBN 1-898697-08-6.

- Gray, Peter; Thetford, Owen (1962). German Aircraft of the First World War. London: Putman.

- Hart, Peter (2005). Bloody April: Slaughter in the Skies over Arras, 1917. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0297846213.

- Mackersley, Ian (2012). No Empty Chairs: The short and heroic lives of the young aviators who fought and died in the First World War. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9780297859949.

- Morris, Alan (1968). Bloody April. Arrow Books. ISBN 0090004507.

- Shores, Christopher; Franks, Norman; Guest, Russell (1991). Above the Trenches: A Complete Record of the Fighter Aces and the Units of the British Empire Air Forces 1915–1920. London: Grub Street. ISBN 0-948817-19-4.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||