Blakeney Point

| Blakeney Point | |

| National Nature Reserve | |

The visitor centre, formerly a lifeboat station | |

| Official name: Blakeney Point Nature Reserve | |

| Country | England |

|---|---|

| County | Norfolk |

| District | North Norfolk |

| Biome | Salt marsh and mudflats |

| Geology | Shingle ridge spit |

| Animal | Migrating and nesting birds, seals |

| Management | National Trust |

| Owner | National Trust |

| For public | Open all year |

| Protection | SSSI, SAC, SPA, Ramsar Site and AONB |

| IUCN | IUCN category IV (habitat/species management area) |

| |

| Wikimedia Commons: Blakeney Point | |

| Website: National Trust Blakeney Point | |

Blakeney Point (officially called Blakeney National Nature Reserve) is a National Nature Reserve situated near to the villages of Blakeney, Morston and Cley next the Sea on the north coast of Norfolk, England. Its main feature is a 6.4 km (4 mi) spit of shingle and sand dunes, but the reserve also includes salt marshes, tidal mudflats and reclaimed farmland. It has been managed by the National Trust since 1912, and lies within the North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest, which is additionally protected through Natura 2000, Special Protection Area (SPA), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Ramsar listings. The reserve is part of both an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), and a World Biosphere Reserve. The Point has been studied for more than a century, following pioneering ecological studies by botanist Francis Wall Oliver and a bird ringing programme initiated by ornithologist Emma Turner.

The area has a long history of human occupation; ruins of a medieval monastery and "Blakeney Chapel" (probably a domestic dwelling) are buried in the marshes. The towns sheltered by the shingle spit were once important harbours, but land reclamation schemes starting in the 17th century resulted in the silting up of the river channels. The reserve is important for breeding birds, especially terns, and its location makes it a major site for migrating birds in autumn. Up to 500 seals may gather at the end of the spit, and its sand and shingle hold a number of specialised invertebrates and plants, including the edible samphire, or "sea asparagus".

The many visitors who come to birdwatch, sail or for other outdoor recreations are important to the local economy, but the land-based activities jeopardize nesting birds and fragile habitats, especially the dunes. Some access restrictions on humans and dogs help to reduce the adverse effects, and trips to see the seals are usually undertaken by boat. The spit is a dynamic structure, gradually moving towards the coast and extending to the west. Land is lost to the sea as the spit rolls forward. The River Glaven can become blocked by the advancing shingle and cause flooding of Cley village, Cley Marshes nature reserve, and the environmentally important reclaimed grazing pastures, so the river has to be realigned every few decades.

Description

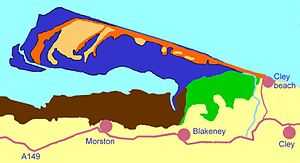

Despite the name, Blakeney Point, like most of the northern part of the marshes in this area, is part of the parish of Cley next the Sea.[1] The main spit runs roughly west to east, and joins the mainland at Cley Beach before continuing onwards as a coastal ridge to Weybourne. It is approximately 6.4 km (4 mi) long,[2] and is composed of a shingle bank which in places is 20 m (65 ft) in width and up to 10 m (33 feet) high. It has been estimated that there are 2.3 million m3 (82 million ft3) of shingle in the spit,[3] 97 per cent of which is derived from flint.[4]

The Point was formed by longshore drift and this movement continues westward; the spit lengthened by 132.1 m (433 ft) between 1886 and 1925.[5] At the western end, the shingle curves south towards the mainland. This feature has developed several times over the years, giving the impression from the air of a series of hooks along the south side of the spit.[6] Salt marshes have formed between the shingle curves and in front of the coasts sheltered by the spit,[5] and sand dunes have accumulated at the Point's western end.[2] Some of the shorter side ridges meet the main ridge at a steep angle due to the southward movement of the latter.[7] There is an area of reclaimed farmland, known as Blakeney Freshes, to the west of Cley Beach Road.[8][9]

Norfolk Coast Path, an ancient long distance footpath, cuts across the south eastern corner of the reserve along the sea wall between the farmland and the salt marshes, and further west at Holme-next-the-Sea the trail joins Peddars Way.[8][10] The tip of Blakeney Point can be reached by walking up the shingle spit from the car park at Cley Beach,[2] or by boats from the quay at Morston. The boat gives good views of the seal colonies and avoids the long walk over a difficult surface.[11] The National Trust has an information centre and tea room at the quay,[12] and a visitor centre on the Point. The centre was formerly a lifeboat station and is open in the summer months.[13] Halfway House, or the Watch House, is a building 2.4 km (1.5 mi) from Cley Beach car park. Originally built in the 19th century as a look-out for smugglers, it was used in succession as a coast guard station, by the Girl Guides, and as a holiday let.[2]

History

To 1912

Norfolk has a long history of human occupation dating back to the Palaeolithic, and has produced significant archaeological finds. Both modern and Neanderthal people were present in the area between 100,000 and 10,000 years ago, before the last glaciation, and humans returned as the ice retreated northwards. The archaeological record is poor until about 20,000 years ago, partly because of the very cold conditions that existed then, but also because the coastline was much further north than at present. As the ice retreated during the Mesolithic (10,000–5,000 BCE), the sea level rose, filling what is now the North Sea. This brought the Norfolk coastline much closer to its present line, so that many ancient sites are now under the sea in an area now known as Doggerland.[14][15] Early Mesolithic flint tools with characteristic long blades up to 15 cm (5.9 in)[16] long found on the present-day coast at Titchwell Marsh date from a time when it was 60–70 km (37–43 mi) from the sea. Other flint tools have been found dating from the Upper Paleolithic (50,000–10,000 BCE) to the Neolithic (5,000–2,500 BCE).[15]

An "eye" is an area of higher ground in the marshes, dry enough to support buildings. Blakeney's former Carmelite friary, founded in 1296 and dissolved in 1538, was built in such a location,[17] and several fragments of plain roof tile and pantiles dating back to the 13th century have been found near the site of its ruins.[18] Originally on the south side of the Glaven, Blakeney Eye had a ditched enclosure during the 11th and 12th centuries, and a building known as "Blakeney Chapel", which was occupied from the 14th century to around 1600, and again in the late 17th century. Despite its name, it is unlikely that it had a religious function. Nearly a third of the mostly 14th- to 16th-century pottery found within the larger and earlier of the two rooms was imported from the continent,[19][20] suggesting significant international trade at this time.[21][22]

The spit sheltered the Glaven ports, Blakeney, Cley-next-the-Sea and Wiveton, which were important medieval harbours. Blakeney sent ships to help Edward I's war efforts in 1301, and between the 14th and 16th centuries it was the only Norfolk port between King's Lynn and Great Yarmouth to have customs officials.[15] Blakeney Church has a second tower at its east end, an unusual feature in a rural parish church. It has been suggested that it acted as a beacon for mariners,[23] perhaps by aligning it with the taller west tower to guide ships into the navigable channel between the inlet's sandbanks;[21] that this was not always successful is demonstrated by a number of wrecks in the haven, including a carvel-built wooden ship.[15]

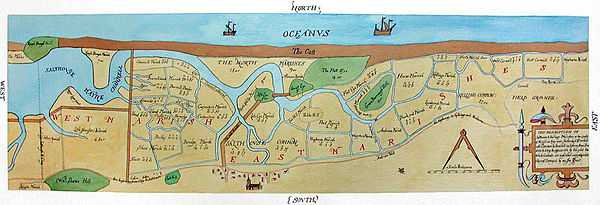

Land reclamation schemes, especially those by Henry Calthorpe in 1640 just to the west of Cley, led to the silting up of the Glaven shipping channel and relocation of Cley's wharf.[24] Further enclosure in the mid-1820s aggravated the problem, and also allowed the shingle ridge at the beach to block the former tidal channel to the Salthouse marshes to the east of Cley.[25] In an attempt to halt the decline, Thomas Telford was consulted in 1822, but his recommendations for reducing the silting were not implemented, and by 1840 almost all of Cley's trade had been lost.[24] The population stagnated, and the value of all property decreased sharply.[25] Blakeney's shipping trade benefited from the silting up of its nearby rival, and in 1817 the channel to the Haven was deepened to improve access. Packet ships ran to Hull and London from 1840, but this trade declined as ships became too large for the harbour.[22]

National Trust era

Shingle Car parks (circles) and roads Marine

In the decades preceding World War I, this stretch of coast became famous for its wildfowling; locals were looking for food, but some more affluent visitors hunted to collect rare birds;[26] Norfolk's first barred warbler was shot on the point in 1884. In 1901, the Blakeney and Cley Wild Bird Protection Society created a bird sanctuary and appointed as its "Watcher", Bob Pinchen, the first of only six men, up to 2012, to hold that post.[27]

In 1910, the owner of the Point, Augustus Cholmondeley Gough-Calthorpe, 6th Baron Calthorpe, leased the land to University College London (UCL), who also purchased the Old Lifeboat House at the end of the spit. When the baron died later that year, his heirs put Blakeney Point up for sale, raising the possibility of development.[28] In 1912, a public appeal initiated by Charles Rothschild and organised by UCL Professor Francis Wall Oliver and Dr Sidney Long enabled the purchase of Blakeney Point from the Calthorpe estate, and the land was then donated to the National Trust.[29] UCL established a research centre at the Old Lifeboat House in 1913,[2] where Oliver and his college pioneered the scientific study of Blakeney Point.[30] The building is still used by students, and also acts as an information centre.[2] Despite formal protection, the tern colony was not fenced off until the 1960s.[27]

The Point was designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in 1954, along with the adjacent Cley Marshes reserve, and subsumed into the newly created 7,700-hectare (19,000-acre) North Norfolk Coast SSSI in 1986. The larger area is now additionally protected through Natura 2000, Special Protection Area (SPA) and Ramsar listings, IUCN category IV (habitat/species management area)[31] and is part of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[32] The Point became a National Nature Reserve (NNR) in 1994,[33] and the coast from Holkham NNR to Salthouse, together with Scolt Head Island, became a Biosphere Reserve in 1976.[34][35]

Fauna and flora

Birds

Blakeney Point has been designated as one of the most important sites in Europe for nesting terns by the government's Joint Nature Conservation Committee.[36] In the early 1900s, the small colonies of common and little terns were badly affected by egg-taking, disturbance and shooting, but as protection improved the common terns population rose to 2,000 pairs by mid-century, although it subsequently declined to no more than 165 pairs by 2000, perhaps due to predation. Sandwich terns were a scarce breeder until the 1970s, but there were 4,000 pairs by 1992. Blakeney is the most important site in Britain for both Sandwich and little terns, the roughly 200 pairs of the latter species amounting to eight per cent of the British population. The 2,000 pairs of black-headed gulls sharing the breeding area with the terns are believed to protect the colony as a whole from predators like red foxes. Other nesting birds include about 20 pairs of Arctic terns and a few Mediterranean gulls in the tern colony, ringed plovers and oystercatchers on the shingle and common redshanks on the salt marsh. The waders' breeding success has been compromised by human disturbance and predation by gulls, weasels and stoats, with ringed plovers particularly affected, declining to 12 pairs in 2012 compared to 100 pairs twenty years previously.[27] The pastures contain breeding northern lapwings, and species such as sedge and reed warblers and bearded tits are found in patches of common reed.[8]

The Point juts into the sea on a north-facing coast, which means that migrant birds may be found in spring and autumn, sometimes in huge numbers when the weather conditions force them towards land.[37][38] Numbers are relatively low in spring, but autumn can produce large "falls", such as the hundreds of European robins on 1 October 1951 or more than 400 common redstarts, on 18 September 1995. The common birds are regularly accompanied by scarcer species like greenish warblers, great grey shrikes or Richard's pipits. Seabirds may be sighted passing the Point, and migrating waders feed on the marshes at this time of year.[27] Vagrant rarities have turned up when the weather is appropriate,[39] including a Fea's or Zino's petrel in 1997, a trumpeter finch in 2008, and an alder flycatcher in 2010. Ornithologist and pioneering bird photographer Emma Turner started ringing common terns on the Point in 1909, and the use of this technique for migration studies has continued since. A notable recovery was a Sandwich tern killed for food in Angola, and a Radde's warbler trapped for ringing in 1961 was only the second British record of this species at that time.[27] In the winter, the marshes hold golden plovers and wildfowl including common shelduck, Eurasian wigeon, brent geese and common teal,[8] while common scoters, common eiders, common goldeneyes and red-breasted mergansers swim offshore.[40]

Other animals

Blakeney Point has a mixed colony of about 500 harbour and grey seals. The harbour seals have their young between June and August, and the pups, which can swim almost immediately, may be seen on the mud flats. Grey seals breed in winter, between November and January; their young cannot swim until they have lost their first white coat, so they are restricted to dry land for their first three or four weeks, and can be viewed on the beach during this period.[13] Grey seals colonised a site in east Norfolk in 1993, and started breeding regularly at Blakeney in 2001. It is possible that they now outnumber harbour seals off the Norfolk coast.[41] Seal-watching boat trips run from Blakeney and Morston harbours, giving good views without disturbing the seals.[13] The corpses of 24 female or juvenile harbour seals were found in the Blakeney area between March 2009 and August 2010, each with spirally cut wounds consistent with the animal having been drawn through a ducted propeller.[42]

The rabbit population can grow to a level at which their grazing and burrowing adversely affects the fragile dune vegetation. When rabbit numbers are reduced by myxomatosis, the plants recover, although those that are toxic to rabbits, like ragwort, then become less common due to increased competition from the edible species.[43][44] The rabbits may be killed by carnivores such as red foxes, weasels and stoats.[27] Records of mammals that are rare in the NNR area include red deer swimming in the haven, a hedgehog and a beached Sowerby's beaked whale.[45]

An insect survey in September 2009 recorded 187 beetle species, including two new to Norfolk, the rove beetle Phytosus nigriventris and the fungus beetle Leiodes ciliaris, and two very rarely seen in the county, the sap beetle Nitidula carnaria and the clown beetle Gnathoncus nanus. There were also 24 types of spider, and the five ant species included the nationally rare Myrmica specioides.[46] The rare millipede Thalassisobates littoralis, a specialist of coastal shingle habitats, was found here in 1972,[47] and a red-veined darter appeared in 2012.[48] Tens of thousands of migrant turnip sawflies were recorded for a few days in late summer 2006, along with red-eyed damselflies.[49] The Silver Y moth also appears in large numbers in some years.[50]

The many inhabitants of the tidal flats include lugworms, polchaete worms, sand hoppers and other amphipod crustaceans, and gastropod molluscs. These molluscs feed on the algae growing on the surface of the mud, and include the tiny Hydrobia, an important food for waders because of its abundance at densities of more than 130,000 m−2. Bivalve molluscs include the edible common cockle, although it is not harvested here.[51]

Plants

Grasses such as sea couch grass and sea poa grass have an important function in the driest areas of the marshes, and on the coastal dunes, where marram grass, sand couch-grass, lyme-grass and grey hair-grass help to bind the sand. Sea holly, sand sedge, bird's-foot trefoil and pyramidal orchid are other specialists of this arid habitat.[11][32] Some specialised mosses and lichens are found on the dunes, and help to consolidate the sand;[52] a survey in September 2009 found 41 lichen species.[46] The plant distribution is influenced by the dunes' age as well as their moisture content, the deposits becoming less alkaline as calcium carbonate from animal shells is leached out of the sand to be replaced by more acidic humus from plant decomposition products. Marram grass is particularly discouraged by the change in acidity.[53] A similar pattern is seen with mosses and lichens, with the various areas of the dunes containing different species according to the acidity of the sand.[54] At least four moss species have been identified as important in dune stabilization, since they help to consolidate the sand, add nutrients as they decompose, and pave the way for more exacting plant species.[55] The moss and lichen flora of Blakeney Point differs markedly from that of lime-rich dunes on the western coasts of the UK.[54] Non-native tree lupins have become established near the Lifeboat House, where they now grow wild.[56][57]

The shingle ridge attracts biting stonecrop, sea campion, yellow horned poppy, sea thrift, bird's foot trefoil and sea beet.[32] In the damper areas, where the shingle adjoins salt marsh, rock sea lavender, matted sea lavender and scrubby sea-blite also thrive, although they are scarce in Britain away from the Norfolk coast.[11] The saltmarsh contains European glasswort and common cord grass in the most exposed regions, with a succession of plants following on as the marsh becomes more established: first sea aster, then mainly sea lavender, with sea purslane in the creeks, and smaller areas of sea plantain and other common marsh plants.[32] Six previously unknown diatom species were found in the waters around the point in1952, along with six others not previously recorded in Britain.[58]

European glasswort is picked between May and September and sold locally as "samphire".[59] It is a fleshy plant which when blanched or steamed has a taste which leads to its alternative name of "sea asparagus", and it is often eaten with fish.[60][61] It can also be eaten raw when young.[62] Glasswort is also a favourite food for the rabbits, which will venture onto the saltmarsh in search of this succulent plant.[63]

Recreation

The 7.7 million day visitors and 5.5 million who made overnight stays on the Norfolk coast in 1999 are estimated to have spent £122 million, and secured the equivalent of 2,325 full-time jobs in that area. A 2005 survey at six North Norfolk coastal sites, including Blakeney, Cley and Morston found that 39 per cent of visitors gave birdwatching as the main purpose of their visit.[35] The villages nearest to the Point, Blakeney and Cley, had the highest per capita spend per visitor of those surveyed, and Cley was one of the two sites with the highest proportion of pre-planned visits. The equivalent of 52 full-time jobs in the Cley and Blakeney area are estimated to result from the £2.45 million spent locally by the visiting public.[64] In addition to birdwatching and boat trips to see the seals, sailing and walking are the other significant tourist activities in the area.[8][22]

The large number of visitors at coastal sites sometimes has negative effects. Wildlife may be disturbed, a frequent difficulty for species that breed in exposed areas such as ringed plovers and little terns, and also for wintering geese.[65] During the breeding season, the main breeding areas for terns and seals are fenced off and signposted.[2] Plants can be trampled, which is a particular problem in sensitive habitats such as sand dunes and vegetated shingle.[65] A boardwalk made from recycled plastic crosses the large sand dunes near the end of the Point, which helps to reduce erosion.[2] It was installed in 2009 at a cost of £35,000 to replace its much less durable wooden predecessor.[66] Dogs are not allowed from April to mid-August because of the risk to ground-nesting birds, and must be on a lead or closely controlled at other times.[2]

The Norfolk Coast Partnership, a grouping of conservation and environmental bodies, divide the coast and its hinterland into three zones for tourism development purposes. Blakeney Point, along with Holme Dunes and Holkham dunes, is considered to be a sensitive habitat already suffering from visitor pressure, and therefore designated as a red-zone area with no development or parking improvements to be recommended. The rest of the reserve is placed in the orange zone, for locations with fragile habitats but less tourism pressure.[67]

Coastal changes

The spit is a relatively young feature in geological terms, and in recent centuries it has been extending westwards and landwards through tidal and storm action.[11] This growth is thought to have been enhanced by the reclamation of the salt marshes along this coast in recent centuries, which removed a natural barrier to the movement of shingle.[68] The amount of shingle moved by a single storm can be "spectacular";[11][27] the spit has sometimes been breached, becoming an island for a time, and this may happen again.[1][5] The northernmost part of Snitterley (now Blakeney) village was lost to the sea in the early Middle Ages, probably due to a storm.[69] In the last two hundred years, maps have been accurate enough for the distance from the Blakeney Chapel ruins to the sea to be measured. The 400 m (440 yd) in 1817 had become 320 m (350 yd) by 1835, 275 m (300 yd) in 1907, and 195 m (215 yd) by the end of the 20th century.[1] The spit is moving towards the mainland at about 1 m (1 yd) per year;[70] and several former raised islands or "eyes" have already disappeared, first covered by the advancing shingle, and then lost to the sea.[9] The massive 1953 flood overran the main beach, and only the highest dune tops remained above water. Sand was washed into the salt marshes, and the extreme tip of the point was breached, but as with other purely natural parts of the coast, like Scolt Head Island, little lasting damage was done.[29]

Landward movement of the shingle meant that the channel of the Glaven was becoming blocked increasingly often by 2004. This led to flooding of Cley village and the environmentally important Blakeney freshwater marshes.[9] The Environment Agency considered a number of remedial options. It concluded that attempting to hold back the shingle or breaching the spit to create a new outlet for the Glaven would be expensive and probably ineffective, and doing nothing would be environmentally damaging.[70] The Agency decided to create a new route for the river to the south of its original line,[71] and work to realign a 550 m (600 yd) stretch of river 200 m (220 yd) further south was completed in 2007 at a cost of about £1.5 million.[72] The Glaven had previously been realigned from an earlier, more northerly, course in 1922.[9] The ruins of Blakeney Chapel are now to the north of the river embankment, and essentially unprotected from coastal erosion, since the advancing shingle will no longer be swept away by the stream. The chapel will be buried by a ridge of shingle as the spit continues to move south, and then lost to the sea,[73] perhaps within 20–30 years.[71]

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wright, John (1999). "The chapel on Blakeney Eye: some documentary evidence". Glaven Historian 2: 26–33.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 "Blakeney Point coastal walk to Lifeboat House". Blakeney National Nature Reserve, Morston, Norfolk. National Trust. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ↑ Bridges (1998) p. 39.

- ↑ Steers, J A in Allison & Morley (1989) p. 24.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 May, V J (2003) "North Norfolk Coast" in May (2003) pp. 1–19.

- ↑ Tansley (1939) pp. 848–849.

- ↑ Steers, J A in Allison & Morley (1989) p. 19.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Coastal wildlife walk Blakeney Freshes, Norfolk". National Trust. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Carnell, Peter (1999). "The chapel on Blakeney Eye: initial results of field surveys". Glaven Historian 2: 34–45.

- ↑ "Peddars Way/Norfolk Coast Path". National Trails. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 "Blakeney Point National Nature Reserve". Natural England. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ↑ "Facilities & access". Blakeney National Nature Reserve. National Trust. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Dorling Kindersley (2009) p. 214.

- ↑ Coles, Bryony. "The Doggerland project". Research projects. University of Exeter. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Robertson et al. (2005) pp. 9–22.

- ↑ Murphy (2009) p. 14.

- ↑ Robertson et al. (2005) p. 36.

- ↑ Robertson et al. (2005) p. 143.

- ↑ Lee, Richard (2006). "A report on the archaeological excavation of 'Blakeney Chapel'". Glaven Historian 9: 3–21.

- ↑ Birks (2003) pp. 1–28.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Robinson (2006) pp. 3–5.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Pevsner & Wilson (2002) pp. 394–397.

- ↑ "Church of St Nicholas, Blakeney". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Pevsner & Wilson (2002) p. 435.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Hume, Joseph. "Port of Cley and Blakeney" in appendix to Tidal Harbours Commission (1846). Second report of the commissioners. London: W Clowes & Son. pp. 83a–84a.

- ↑ Bishop (1983) pp. 9–13.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 Stubbing, Edward (2012). "The birds of Blakeney Point: 100 years of National Trust ownership". British Birds 105 (9): 520–529.

- ↑ Ayres (2012) p. 123.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Allison H & Morley J in Allison & Morley (1989) pp. 7–8.

- ↑ "Blakeney Point". University College London Department of genetics, evolution and environment. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ↑ "Blakeney National Nature Reserve". protectedplanet.net. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 "North Norfolk Coast". SSSI citations. Natural England. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ↑ White, D J B (2005). "Blakeney Point and University College London". The Glaven Historian 8: 17–20.

- ↑ "North Norfolk Coast Biosphere Reserve Information". UNESCO – Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme Biosphere Reserves Directory. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Liley (2008) pp. 4–6.

- ↑ "North Norfolk Coast". SPA description. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ↑ Elkins (1988) pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Newton (2010) pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Newton (2010) p. 50.

- ↑ Allison (1989) pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Skeate, Eleanor R; Perrow, Martin R; Gilroy, James J (2012). "Likely effects of construction of Scroby Sands offshore wind farm on a mixed population of harbour Phoca vitulina and grey Halichoerus grypus seals". Marine Pollution Bulletin 64 (4): 872–881. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.01.029. PMID 22333892.

- ↑ Thompson et al (2010) pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Elton (1979) pp. 167–168.

- ↑ White, D J B (1961). "Some observations on the vegetation of Blakeney Point, Norfolk, following the disappearance of the rabbits in 1954". Journal of Ecology 49 (1): 113–118. doi:10.2307/2257428.

- ↑ Barkham, Patrick (24 August 2012). "Do we still need nature reserves?". The Guardian (London: Guardian Media Group). Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Rare beetles found at Blakeney National Nature Reserve". BBC Norfolk. Norwich: British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ Blower (1985) pp. 98–101.

- ↑ "Migrant insect summary – end of June 2012". Atropos. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ↑ Knight, Guy. "Large numbers of the turnip sawfly Athalia rosae (L.)". Newsletter 2, January 2007. Sawfly Study Group. p. 11. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ Foster, W A in Allison & Morley (1989) p. 79.

- ↑ Barnes, R S K in Allison & Morley (1989) pp. 67–75.

- ↑ Tansley (1939) p. 855.

- ↑ Gorham, Eville (1958). "Soluble salts in dune sands from Blakeney Point in Norfolk". Journal of Ecology 46 (2): 373–379. doi:10.2307/2257401.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Richards, P W (1929). "Notes on the ecology of the bryophytes and lichens at Blakeney Point, Norfolk". Journal of Ecology 17 (1): 127–140. doi:10.2307/2255917.

- ↑ Lodge, E in Allison & Morley (1989) pp. 60–63.

- ↑ White, D J B in Allison & Morley (1989) p. 41.

- ↑ Mabey (1996) p. 226.

- ↑ Salah, M M (1952). "Diatoms from Blakeney Point, Norfolk. New Species and new records for Great Britain". Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society 72 (3): 156–169. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2818.1952.tb01971.x.

- ↑ Stannard & Smith (2005) p. 34

- ↑ Knights & Phillips (1979) p. 49.

- ↑ Sweetser & Laurie (2009) p. 187.

- ↑ Fearnley-Whittingstall, Hugh (June 2007). "Join the samphire brigade". The Guardian (London: Guardian Media Group). Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ Rowan, William (1913). "Note on the food plants of rabbits on Blakeney Point, Norfolk". Journal of Ecology 1 (4): 273–274. doi:10.2307/2255570.

- ↑ "Valuing Norfolk's Coast". Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Liley (2008) pp. 10–14.

- ↑ Wood, David (2009). "A new boardwalk on Blakeney Point". Views 46: 58.

- ↑ Scott Wilson Ltd (2006) pp. 5–6.

- ↑ East Anglia Coastal Group (2010) pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Muir (2008) p. 103.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Gray (2004) pp. 363–365.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Murphy (2009) p. 9.

- ↑ "Case Study Report 2 Blakeney Freshes River Glaven Realignment and Cley to Salthouse Drainage Improvements". Coastal Schemes with Multiple Funders and Objectives FD2635. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), Environment Agency, Maslem Environmental. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Blakeney Chapel SAM (Scheduled Ancient Monument), North Norfolk". HELM (Historic Environment Local Management). English Heritage. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

Cited texts

- Allison, Hilary; Morley, John, eds. (1989). Blakeney Point and Scolt Head Island. Norwich: National Trust. ISBN 0-9514717-0-8.

- Ayres, Peter G (2012). Shaping Ecology: The Life of Arthur Tansley. London: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-470-67156-4.

- Birks, Chris (2003). Report on an archaeological evaluation at Blakeney Freshes, Cley next the Sea: report No. 808. Norwich: Norfolk Archaeological Unit.

- Bishop, Billy (1983). Cley Marsh and its Birds. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-180-9.

- Blower, J Gordon (1985). Millipedes: Keys and Notes for the Identification of the Species. Leiden: Backhuys. ISBN 90-04-07698-0.

- Bridges, E M (1998). Classic Landforms of the North Norfolk Coast. Sheffield: Geographical Association. ISBN 1-899085-53-X.

- Dorling Kindersley (2009). RSPB Where to go wild in Britain. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 1-4053-3512-2.

- East Anglia Coastal Group (2010). North Norfolk shoreline management plan. Peterborough: Environment Agency.

- Elkins, Norman (1988). Weather and Bird Behaviour. Waterhouses, Staffordshire: Poyser. ISBN 0-85661-051-8.

- Elton, Charles Sutherland (1979). The Pattern of Animal Communities. London: Chapman & Hal. ISBN 0-412-21880-1.

- Gray, J M (2004). Geodiversity: valuing and conserving abiotic nature. Edinburgh: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-470-84896-0.

- Knights, B; Phillips, A J (1979). Estuarine and Coastal Land Reclamation and Water Storage. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate. ISBN 0-566-00252-3.

- Liley, D (2008). Development and the north Norfolk coast. Scoping document on the issues relating to access. Wareham, Dorset: Footprint Ecology. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012.

- Mabey, Richard (1996). Flora Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 1-85619-377-2.

- May, V J (2003). Geological Conservation Review: volume 28: Coastal geomorphology of Great Britain. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee. ISBN 1-86107-484-0.

- Muir, Richard (2008). The lost villages of Britain. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press Ltd. ISBN 0-7509-5039-0.

- Murphy, Peter (2009). The English coast: a history and a prospect. London: Continuum International Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84725-143-5.

- Newton, Ian (2010). Bird Migration: Collins New Naturalist Library (113). London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-730732-2.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Wilson, Bill (2002). The Buildings Of England Norfolk I: Norwich and North-East Norfolk. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09607-0.

- Robertson, David; Crawley, Peter; Barker, Adam; Whitmore, Sandrine (2005). Norfolk Archaeological Unit Report No. 1045: Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Archaeological Survey. Norwich: Norfolk Archaeological Unit. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012.

- Robinson, Geoffey H (c. 2006). St Nicholas, Blakeney. Norwich: Geoffrey H Robinson.

- Scott Wilson Ltd (2006). Tourism benefit & impacts analysis in the Norfolk coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Norwich: Norfolk Coast Partnership. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012.

- Stannard, David; Smith, George (2005). Fishing Up the Moon: Norfolk Seafood Cookery. Dereham, Norfolk: Larks Press. ISBN 1-904006-26-4.

- Sweetser, Wendy; Laurie, Jane (2009). The Connoisseur's Guide to Fish & Seafood. New York: Sterling. ISBN 1-4027-7051-0.

- Tansley, Arthur George (1939). The British islands and their vegetation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thompson, Dave; Bexton, Steve; Brownlow, Andrew; Wood, David; Patterson, Tony; Pye, Ken; Lonergan, Mike; Milne, Ryan (2010). Report on recent seal mortalities in UK waters caused by extensive lacerations. St Andrews: Sea Mammal Research Unit.

External links

Media related to Blakeney Point at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Blakeney Point at Wikimedia Commons- Open Street Map

Coordinates: 52°58′38″N 0°58′40″E / 52.9772°N 0.9778°E

| ||||||||||