Black hole

| General relativity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|

||||||

|

Fundamental concepts |

||||||

|

||||||

A black hole is a mathematically defined region of spacetime exhibiting such a strong gravitational pull that no particle or electromagnetic radiation can escape from it.[1] The theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass can deform spacetime to form a black hole.[2] The boundary of the region from which no escape is possible is called the event horizon. Although crossing the event horizon has enormous effect on the fate of the object crossing it, it appears to have no locally detectable features. In many ways a black hole acts like an ideal black body, as it reflects no light.[3][4] Moreover, quantum field theory in curved spacetime predicts that event horizons emit Hawking radiation, with the same spectrum as a black body of a temperature inversely proportional to its mass. This temperature is on the order of billionths of a kelvin for black holes of stellar mass, making it essentially impossible to observe.

Objects whose gravitational fields are too strong for light to escape were first considered in the 18th century by John Michell and Pierre-Simon Laplace. The first modern solution of general relativity that would characterize a black hole was found by Karl Schwarzschild in 1916, although its interpretation as a region of space from which nothing can escape was first published by David Finkelstein in 1958. Long considered a mathematical curiosity, it was during the 1960s that theoretical work showed black holes were a generic prediction of general relativity. The discovery of neutron stars sparked interest in gravitationally collapsed compact objects as a possible astrophysical reality.

Black holes of stellar mass are expected to form when very massive stars collapse at the end of their life cycle. After a black hole has formed, it can continue to grow by absorbing mass from its surroundings. By absorbing other stars and merging with other black holes, supermassive black holes of millions of solar masses (M☉) may form. There is general consensus that supermassive black holes exist in the centers of most galaxies.

Despite its invisible interior, the presence of a black hole can be inferred through its interaction with other matter and with electromagnetic radiation such as visible light. Matter falling onto a black hole can form an accretion disk heated by friction, forming some of the brightest objects in the universe. If there are other stars orbiting a black hole, their orbit can be used to determine its mass and location. Such observations can be used to exclude possible alternatives (such as neutron stars). In this way, astronomers have identified numerous stellar black hole candidates in binary systems, and established that the radio source known as Sgr A*, at the core of our own Milky Way galaxy, contains a supermassive black hole of about 4.3 million M☉.

History

The idea of a body so massive that even light could not escape was first put forward by John Michell in a letter written to Henry Cavendish in 1783 of the Royal Society:

If the semi-diameter of a sphere of the same density as the Sun were to exceed that of the Sun in the proportion of 500 to 1, a body falling from an infinite height towards it would have acquired at its surface greater velocity than that of light, and consequently supposing light to be attracted by the same force in proportion to its vis inertiae, with other bodies, all light emitted from such a body would be made to return towards it by its own proper gravity.—John Michell[6]

In 1796, mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace promoted the same idea in the first and second editions of his book Exposition du système du Monde (it was removed from later editions).[7][8] Such "dark stars" were largely ignored in the nineteenth century, since it was not understood how a massless wave such as light could be influenced by gravity.[9]

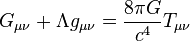

General relativity

In 1915, Albert Einstein developed his theory of general relativity, having earlier shown that gravity does influence light's motion. Only a few months later, Karl Schwarzschild found a solution to the Einstein field equations, which describes the gravitational field of a point mass and a spherical mass.[10] A few months after Schwarzschild, Johannes Droste, a student of Hendrik Lorentz, independently gave the same solution for the point mass and wrote more extensively about its properties.[11][12] This solution had a peculiar behaviour at what is now called the Schwarzschild radius, where it became singular, meaning that some of the terms in the Einstein equations became infinite. The nature of this surface was not quite understood at the time. In 1924, Arthur Eddington showed that the singularity disappeared after a change of coordinates (see Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates), although it took until 1933 for Georges Lemaître to realize that this meant the singularity at the Schwarzschild radius was an unphysical coordinate singularity.[13]

In 1931, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar calculated, using special relativity, that a non-rotating body of electron-degenerate matter above a certain limiting mass (now called the Chandrasekhar limit at 1.4 M☉) has no stable solutions.[14] His arguments were opposed by many of his contemporaries like Eddington and Lev Landau, who argued that some yet unknown mechanism would stop the collapse.[15] They were partly correct: a white dwarf slightly more massive than the Chandrasekhar limit will collapse into a neutron star,[16] which is itself stable because of the Pauli exclusion principle. But in 1939, Robert Oppenheimer and others predicted that neutron stars above approximately 3 M☉ (the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit) would collapse into black holes for the reasons presented by Chandrasekhar, and concluded that no law of physics was likely to intervene and stop at least some stars from collapsing to black holes.[17]

Oppenheimer and his co-authors interpreted the singularity at the boundary of the Schwarzschild radius as indicating that this was the boundary of a bubble in which time stopped. This is a valid point of view for external observers, but not for infalling observers. Because of this property, the collapsed stars were called "frozen stars",[18] because an outside observer would see the surface of the star frozen in time at the instant where its collapse takes it inside the Schwarzschild radius.

Golden age

In 1958, David Finkelstein identified the Schwarzschild surface as an event horizon, "a perfect unidirectional membrane: causal influences can cross it in only one direction".[19] This did not strictly contradict Oppenheimer's results, but extended them to include the point of view of infalling observers. Finkelstein's solution extended the Schwarzschild solution for the future of observers falling into a black hole. A complete extension had already been found by Martin Kruskal, who was urged to publish it.[20]

These results came at the beginning of the golden age of general relativity, which was marked by general relativity and black holes becoming mainstream subjects of research. This process was helped by the discovery of pulsars in 1967,[21][22] which, by 1969, were shown to be rapidly rotating neutron stars.[23] Until that time, neutron stars, like black holes, were regarded as just theoretical curiosities; but the discovery of pulsars showed their physical relevance and spurred a further interest in all types of compact objects that might be formed by gravitational collapse.

In this period more general black hole solutions were found. In 1963, Roy Kerr found the exact solution for a rotating black hole. Two years later, Ezra Newman found the axisymmetric solution for a black hole that is both rotating and electrically charged.[24] Through the work of Werner Israel,[25] Brandon Carter,[26][27] and David Robinson[28] the no-hair theorem emerged, stating that a stationary black hole solution is completely described by the three parameters of the Kerr–Newman metric; mass, angular momentum, and electric charge.[29]

At first, it was suspected that the strange features of the black hole solutions were pathological artifacts from the symmetry conditions imposed, and that the singularities would not appear in generic situations. This view was held in particular by Vladimir Belinsky, Isaak Khalatnikov, and Evgeny Lifshitz, who tried to prove that no singularities appear in generic solutions. However, in the late 1960s Roger Penrose[30] and Stephen Hawking used global techniques to prove that singularities appear generically.[31]

Work by James Bardeen, Jacob Bekenstein, Carter, and Hawking in the early 1970s led to the formulation of black hole thermodynamics.[32] These laws describe the behaviour of a black hole in close analogy to the laws of thermodynamics by relating mass to energy, area to entropy, and surface gravity to temperature. The analogy was completed when Hawking, in 1974, showed that quantum field theory predicts that black holes should radiate like a black body with a temperature proportional to the surface gravity of the black hole.[33]

The first use of the term "black hole" in print was by journalist Ann Ewing in her article "'Black Holes' in Space", dated 18 January 1964, which was a report on a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[34] John Wheeler used the term "black hole" at a lecture in 1967, leading some to credit him with coining the phrase. After Wheeler's use of the term, it was quickly adopted in general use.

Properties and structure

The no-hair theorem states that, once it achieves a stable condition after formation, a black hole has only three independent physical properties: mass, charge, and angular momentum.[29] Any two black holes that share the same values for these properties, or parameters, are indistinguishable according to classical (i.e. non-quantum) mechanics.

These properties are special because they are visible from outside a black hole. For example, a charged black hole repels other like charges just like any other charged object. Similarly, the total mass inside a sphere containing a black hole can be found by using the gravitational analog of Gauss's law, the ADM mass, far away from the black hole.[35] Likewise, the angular momentum can be measured from far away using frame dragging by the gravitomagnetic field.

When an object falls into a black hole, any information about the shape of the object or distribution of charge on it is evenly distributed along the horizon of the black hole, and is lost to outside observers. The behavior of the horizon in this situation is a dissipative system that is closely analogous to that of a conductive stretchy membrane with friction and electrical resistance—the membrane paradigm.[36] This is different from other field theories like electromagnetism, which do not have any friction or resistivity at the microscopic level, because they are time-reversible. Because a black hole eventually achieves a stable state with only three parameters, there is no way to avoid losing information about the initial conditions: the gravitational and electric fields of a black hole give very little information about what went in. The information that is lost includes every quantity that cannot be measured far away from the black hole horizon, including approximately conserved quantum numbers such as the total baryon number and lepton number. This behavior is so puzzling that it has been called the black hole information loss paradox.[37][38]

Physical properties

The simplest static black holes have mass but neither electric charge nor angular momentum. These black holes are often referred to as Schwarzschild black holes after Karl Schwarzschild who discovered this solution in 1916.[10] According to Birkhoff's theorem, it is the only vacuum solution that is spherically symmetric.[39] This means that there is no observable difference between the gravitational field of such a black hole and that of any other spherical object of the same mass. The popular notion of a black hole "sucking in everything" in its surroundings is therefore only correct near a black hole's horizon; far away, the external gravitational field is identical to that of any other body of the same mass.[40]

Solutions describing more general black holes also exist. Charged black holes are described by the Reissner–Nordström metric, while the Kerr metric describes a rotating black hole. The most general stationary black hole solution known is the Kerr–Newman metric, which describes a black hole with both charge and angular momentum.[41]

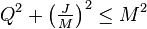

While the mass of a black hole can take any positive value, the charge and angular momentum are constrained by the mass. In Planck units, the total electric charge Q and the total angular momentum J are expected to satisfy

for a black hole of mass M. Black holes saturating this inequality are called extremal. Solutions of Einstein's equations that violate this inequality exist, but they do not possess an event horizon. These solutions have so-called naked singularities that can be observed from the outside, and hence are deemed unphysical. The cosmic censorship hypothesis rules out the formation of such singularities, when they are created through the gravitational collapse of realistic matter.[2] This is supported by numerical simulations.[42]

Due to the relatively large strength of the electromagnetic force, black holes forming from the collapse of stars are expected to retain the nearly neutral charge of the star. Rotation, however, is expected to be a common feature of compact objects. The black-hole candidate binary X-ray source GRS 1915+105[43] appears to have an angular momentum near the maximum allowed value.

| Class | Mass | Size |

|---|---|---|

| Supermassive black hole | ~105–1010 MSun | ~0.001–400 AU |

| Intermediate-mass black hole | ~103 MSun | ~103 km ≈ REarth |

| Stellar black hole | ~10 MSun | ~30 km |

| Micro black hole | up to ~MMoon | up to ~0.1 mm |

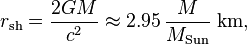

Black holes are commonly classified according to their mass, independent of angular momentum J or electric charge Q. The size of a black hole, as determined by the radius of the event horizon, or Schwarzschild radius, is roughly proportional to the mass M through

where rsh is the Schwarzschild radius and MSun is the mass of the Sun.[44] This relation is exact only for black holes with zero charge and angular momentum; for more general black holes it can differ up to a factor of 2.

Event horizon

| Far away from the black hole, a particle can move in any direction, as illustrated by the set of arrows. It is only restricted by the speed of light. |

| Closer to the black hole, spacetime starts to deform. There are more paths going towards the black hole than paths moving away.[Note 1] |

| Inside of the event horizon, all paths bring the particle closer to the center of the black hole. It is no longer possible for the particle to escape. |

The defining feature of a black hole is the appearance of an event horizon—a boundary in spacetime through which matter and light can only pass inward towards the mass of the black hole. Nothing, not even light, can escape from inside the event horizon. The event horizon is referred to as such because if an event occurs within the boundary, information from that event cannot reach an outside observer, making it impossible to determine if such an event occurred.[46]

As predicted by general relativity, the presence of a mass deforms spacetime in such a way that the paths taken by particles bend towards the mass.[47] At the event horizon of a black hole, this deformation becomes so strong that there are no paths that lead away from the black hole.

To a distant observer, clocks near a black hole appear to tick more slowly than those further away from the black hole.[48] Due to this effect, known as gravitational time dilation, an object falling into a black hole appears to slow down as it approaches the event horizon, taking an infinite time to reach it.[49] At the same time, all processes on this object slow down, for a fixed outside observer, causing emitted light to appear redder and dimmer, an effect known as gravitational redshift.[50] Eventually, at a point just before it reaches the event horizon, the falling object becomes so dim that it can no longer be seen.

On the other hand, an indestructible observer falling into a black hole does not notice any of these effects as he crosses the event horizon. According to his own clock, which appears to him to tick normally, he crosses the event horizon after a finite time without noting any singular behaviour. In particular, he is unable to determine exactly when he crosses it, as it is impossible to determine the location of the event horizon from local observations.[51]

The shape of the event horizon of a black hole is always approximately spherical.[Note 2][54] For non-rotating (static) black holes the geometry is precisely spherical, while for rotating black holes the sphere is somewhat oblate.

Singularity

At the center of a black hole as described by general relativity lies a gravitational singularity, a region where the spacetime curvature becomes infinite.[55] For a non-rotating black hole, this region takes the shape of a single point and for a rotating black hole, it is smeared out to form a ring singularity lying in the plane of rotation.[56] In both cases, the singular region has zero volume. It can also be shown that the singular region contains all the mass of the black hole solution.[57] The singular region can thus be thought of as having infinite density.

Observers falling into a Schwarzschild black hole (i.e., non-rotating and not charged) cannot avoid being carried into the singularity, once they cross the event horizon. They can prolong the experience by accelerating away to slow their descent, but only up to a point; after attaining a certain ideal velocity, it is best to free fall the rest of the way.[58] When they reach the singularity, they are crushed to infinite density and their mass is added to the total of the black hole. Before that happens, they will have been torn apart by the growing tidal forces in a process sometimes referred to as spaghettification or the "noodle effect".[59]

In the case of a charged (Reissner–Nordström) or rotating (Kerr) black hole, it is possible to avoid the singularity. Extending these solutions as far as possible reveals the hypothetical possibility of exiting the black hole into a different spacetime with the black hole acting as a wormhole.[60] The possibility of traveling to another universe is however only theoretical, since any perturbation will destroy this possibility.[61] It also appears to be possible to follow closed timelike curves (going back to one's own past) around the Kerr singularity, which lead to problems with causality like the grandfather paradox.[62] It is expected that none of these peculiar effects would survive in a proper quantum treatment of rotating and charged black holes.[63]

The appearance of singularities in general relativity is commonly perceived as signaling the breakdown of the theory.[64] This breakdown, however, is expected; it occurs in a situation where quantum effects should describe these actions, due to the extremely high density and therefore particle interactions. To date, it has not been possible to combine quantum and gravitational effects into a single theory, although there exist attempts to formulate such a theory of quantum gravity. It is generally expected that such a theory will not feature any singularities.[65][66]

Photon sphere

The photon sphere is a spherical boundary of zero thickness such that photons moving along tangents to the sphere will be trapped in a circular orbit. For non-rotating black holes, the photon sphere has a radius 1.5 times the Schwarzschild radius. The orbits are dynamically unstable, hence any small perturbation (such as a particle of infalling matter) will grow over time, either setting it on an outward trajectory escaping the black hole or on an inward spiral eventually crossing the event horizon.[67]

While light can still escape from inside the photon sphere, any light that crosses the photon sphere on an inbound trajectory will be captured by the black hole. Hence any light reaching an outside observer from inside the photon sphere must have been emitted by objects inside the photon sphere but still outside of the event horizon.[67]

Other compact objects, such as neutron stars, can also have photon spheres.[68] This follows from the fact that the gravitational field of an object does not depend on its actual size, hence any object that is smaller than 1.5 times the Schwarzschild radius corresponding to its mass will indeed have a photon sphere.

Ergosphere

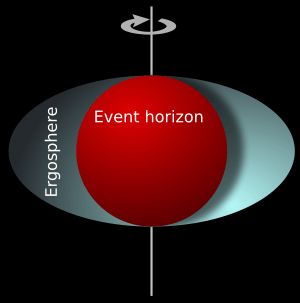

Rotating black holes are surrounded by a region of spacetime in which it is impossible to stand still, called the ergosphere. This is the result of a process known as frame-dragging; general relativity predicts that any rotating mass will tend to slightly "drag" along the spacetime immediately surrounding it. Any object near the rotating mass will tend to start moving in the direction of rotation. For a rotating black hole, this effect becomes so strong near the event horizon that an object would have to move faster than the speed of light in the opposite direction to just stand still.[69]

The ergosphere of a black hole is bounded by the (outer) event horizon on the inside and an oblate spheroid, which coincides with the event horizon at the poles and is noticeably wider around the equator. The outer boundary is sometimes called the ergosurface.

Objects and radiation can escape normally from the ergosphere. Through the Penrose process, objects can emerge from the ergosphere with more energy than they entered. This energy is taken from the rotational energy of the black hole causing it to slow down.[70]

Formation and evolution

Considering the exotic nature of black holes, it may be natural to question if such bizarre objects could exist in nature or to suggest that they are merely pathological solutions to Einstein's equations. Einstein himself wrongly thought that black holes would not form, because he held that the angular momentum of collapsing particles would stabilize their motion at some radius.[71] This led the general relativity community to dismiss all results to the contrary for many years. However, a minority of relativists continued to contend that black holes were physical objects,[72] and by the end of the 1960s, they had persuaded the majority of researchers in the field that there is no obstacle to forming an event horizon.

Once an event horizon forms, Penrose proved that a singularity will form somewhere inside it.[30] Shortly afterwards, Hawking showed that many cosmological solutions describing the Big Bang have singularities without scalar fields or other exotic matter (see Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems). The Kerr solution, the no-hair theorem and the laws of black hole thermodynamics showed that the physical properties of black holes were simple and comprehensible, making them respectable subjects for research.[73] The primary formation process for black holes is expected to be the gravitational collapse of heavy objects such as stars, but there are also more exotic processes that can lead to the production of black holes.

Gravitational collapse

Gravitational collapse occurs when an object's internal pressure is insufficient to resist the object's own gravity. For stars this usually occurs either because a star has too little "fuel" left to maintain its temperature through stellar nucleosynthesis, or because a star that would have been stable receives extra matter in a way that does not raise its core temperature. In either case the star's temperature is no longer high enough to prevent it from collapsing under its own weight.[74] The collapse may be stopped by the degeneracy pressure of the star's constituents, condensing the matter in an exotic denser state. The result is one of the various types of compact star. The type of compact star formed depends on the mass of the remnant—the matter left over after the outer layers have been blown away, such from a supernova explosion or by pulsations leading to a planetary nebula. Note that this mass can be substantially less than the original star—remnants exceeding 5 M☉ are produced by stars that were over 20 M☉ before the collapse.[74]

If the mass of the remnant exceeds about 3–4 M☉ (the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit[17])—either because the original star was very heavy or because the remnant collected additional mass through accretion of matter—even the degeneracy pressure of neutrons is insufficient to stop the collapse. No known mechanism (except possibly quark degeneracy pressure, see quark star) is powerful enough to stop the implosion and the object will inevitably collapse to form a black hole.[74]

The gravitational collapse of heavy stars is assumed to be responsible for the formation of stellar mass black holes. Star formation in the early universe may have resulted in very massive stars, which upon their collapse would have produced black holes of up to 103 M☉. These black holes could be the seeds of the supermassive black holes found in the centers of most galaxies.[75]

While most of the energy released during gravitational collapse is emitted very quickly, an outside observer does not actually see the end of this process. Even though the collapse takes a finite amount of time from the reference frame of infalling matter, a distant observer sees the infalling material slow and halt just above the event horizon, due to gravitational time dilation. Light from the collapsing material takes longer and longer to reach the observer, with the light emitted just before the event horizon forms delayed an infinite amount of time. Thus the external observer never sees the formation of the event horizon; instead, the collapsing material seems to become dimmer and increasingly red-shifted, eventually fading away.[76]

Primordial black holes in the Big Bang

Gravitational collapse requires great density. In the current epoch of the universe these high densities are only found in stars, but in the early universe shortly after the big bang densities were much greater, possibly allowing for the creation of black holes. The high density alone is not enough to allow the formation of black holes since a uniform mass distribution will not allow the mass to bunch up. In order for primordial black holes to form in such a dense medium, there must be initial density perturbations that can then grow under their own gravity. Different models for the early universe vary widely in their predictions of the size of these perturbations. Various models predict the creation of black holes, ranging from a Planck mass to hundreds of thousands of solar masses.[77] Primordial black holes could thus account for the creation of any type of black hole.

High-energy collisions

Gravitational collapse is not the only process that could create black holes. In principle, black holes could be formed in high-energy collisions that achieve sufficient density. As of 2002, no such events have been detected, either directly or indirectly as a deficiency of the mass balance in particle accelerator experiments.[78] This suggests that there must be a lower limit for the mass of black holes. Theoretically, this boundary is expected to lie around the Planck mass (mP = √ħc/G ≈ 1.2×1019 GeV/c2 ≈ 2.2×10−8 kg), where quantum effects are expected to invalidate the predictions of general relativity.[79] This would put the creation of black holes firmly out of reach of any high-energy process occurring on or near the Earth. However, certain developments in quantum gravity suggest that the Planck mass could be much lower: some braneworld scenarios for example put the boundary as low as 1 TeV/c2.[80] This would make it conceivable for micro black holes to be created in the high-energy collisions occurring when cosmic rays hit the Earth's atmosphere, or possibly in the new Large Hadron Collider at CERN. Yet these theories are very speculative, and the creation of black holes in these processes is deemed unlikely by many specialists.[81] Even if micro black holes should be formed in these collisions, it is expected that they would evaporate in about 10−25 seconds, posing no threat to the Earth.[82]

Growth

Once a black hole has formed, it can continue to grow by absorbing additional matter. Any black hole will continually absorb gas and interstellar dust from its direct surroundings and omnipresent cosmic background radiation. This is the primary process through which supermassive black holes seem to have grown.[75] A similar process has been suggested for the formation of intermediate-mass black holes in globular clusters.[83]

Another possibility is for a black hole to merge with other objects such as stars or even other black holes. Although not necessary for growth, this is thought to have been important, especially for the early development of supermassive black holes, which could have formed from the coagulation of many smaller objects.[75] The process has also been proposed as the origin of some intermediate-mass black holes.[84][85]

Evaporation

In 1974, Hawking predicted that black holes are not entirely black but emit small amounts of thermal radiation;[33] this effect has become known as Hawking radiation. By applying quantum field theory to a static black hole background, he determined that a black hole should emit particles in a perfect black body spectrum. Since Hawking's publication, many others have verified the result through various approaches.[86] If Hawking's theory of black hole radiation is correct, then black holes are expected to shrink and evaporate over time because they lose mass by the emission of photons and other particles.[33] The temperature of this thermal spectrum (Hawking temperature) is proportional to the surface gravity of the black hole, which, for a Schwarzschild black hole, is inversely proportional to the mass. Hence, large black holes emit less radiation than small black holes.[87]

A stellar black hole of 1 M☉ has a Hawking temperature of about 100 nanokelvins. This is far less than the 2.7 K temperature of the cosmic microwave background radiation. Stellar-mass or larger black holes receive more mass from the cosmic microwave background than they emit through Hawking radiation and thus will grow instead of shrink. To have a Hawking temperature larger than 2.7 K (and be able to evaporate), a black hole needs to have less mass than the Moon. Such a black hole would have a diameter of less than a tenth of a millimeter.[88]

If a black hole is very small the radiation effects are expected to become very strong. Even a black hole that is heavy compared to a human would evaporate in an instant. A black hole the weight of a car would have a diameter of about 10−24 m and take a nanosecond to evaporate, during which time it would briefly have a luminosity more than 200 times that of the Sun. Lower-mass black holes are expected to evaporate even faster; for example, a black hole of mass 1 TeV/c2 would take less than 10−88 seconds to evaporate completely. For such a small black hole, quantum gravitation effects are expected to play an important role and could even—although current developments in quantum gravity do not indicate so[89]—hypothetically make such a small black hole stable.[90]

Observational evidence

By their very nature, black holes do not directly emit any signals other than the hypothetical Hawking radiation; since the Hawking radiation for an astrophysical black hole is predicted to be very weak, this makes it impossible to directly detect astrophysical black holes from the Earth. A possible exception to the Hawking radiation being weak is the last stage of the evaporation of light (primordial) black holes; searches for such flashes in the past have proven unsuccessful and provide stringent limits on the possibility of existence of light primordial black holes.[92] NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope launched in 2008 will continue the search for these flashes.[93]

Astrophysicists searching for black holes thus have to rely on indirect observations. A black hole's existence can sometimes be inferred by observing its gravitational interactions with its surroundings. A project run by MIT's Haystack Observatory is attempting to observe the event horizon of a black hole directly. Initial results are encouraging.[94]

Accretion of matter

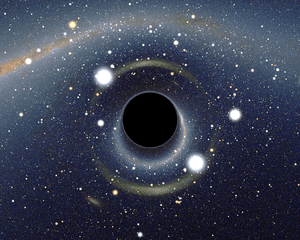

Due to conservation of angular momentum, gas falling into the gravitational well created by a massive object will typically form a disc-like structure around the object. Artist's impressions such as the accompanying representation of a black hole with corona commonly depict the black hole as if it were a flat-space material body hiding the part of the disc just behind it, but detailed mathematical modelling [96] shows that the image of the disc would actually be distorted by light bending in such a way that the upper side of the disc is entirely visible, while there is even a partially visible secondary image of the underside.

Within such a disc, friction will cause angular momentum to be transported outward, allowing matter to fall further inward, releasing potential energy and increasing the temperature of the gas.[97]

In the case of compact objects such as white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes, the gas in the inner regions becomes so hot that it will emit vast amounts of radiation (mainly X-rays), which may be detected by telescopes. This process of accretion is one of the most efficient energy-producing processes known; up to 40% of the rest mass of the accreted material can be emitted in radiation.[97] (In nuclear fusion only about 0.7% of the rest mass will be emitted as energy.) In many cases, accretion discs are accompanied by relativistic jets emitted along the poles, which carry away much of the energy. The mechanism for the creation of these jets is currently not well understood.

As such many of the universe's more energetic phenomena have been attributed to the accretion of matter on black holes. In particular, active galactic nuclei and quasars are believed to be the accretion discs of supermassive black holes.[98] Similarly, X-ray binaries are generally accepted to be binary star systems in which one of the two stars is a compact object accreting matter from its companion.[98] It has also been suggested that some ultraluminous X-ray sources may be the accretion disks of intermediate-mass black holes.[99]

X-ray binaries

X-ray binaries are binary star systems that are luminous in the X-ray part of the spectrum. These X-ray emissions are generally thought to be caused by one of the component stars being a compact object accreting matter from the other (regular) star. The presence of an ordinary star in such a system provides a unique opportunity for studying the central object and determining if it might be a black hole.

If such a system emits signals that can be directly traced back to the compact object, it cannot be a black hole. The absence of such a signal does, however, not exclude the possibility that the compact object is a neutron star. By studying the companion star it is often possible to obtain the orbital parameters of the system and obtain an estimate for the mass of the compact object. If this is much larger than the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit (that is, the maximum mass a neutron star can have before collapsing) then the object cannot be a neutron star and is generally expected to be a black hole.[98]

The first strong candidate for a black hole, Cygnus X-1, was discovered in this way by Charles Thomas Bolton,[100] Louise Webster and Paul Murdin[101] in 1972.[102][103] Some doubt, however, remained due to the uncertainties resultant from the companion star being much heavier than the candidate black hole.[98] Currently, better candidates for black holes are found in a class of X-ray binaries called soft X-ray transients.[98] In this class of system the companion star is relatively low mass allowing for more accurate estimates in the black hole mass. Moreover, these systems are only active in X-ray for several months once every 10–50 years. During the period of low X-ray emission (called quiescence), the accretion disc is extremely faint allowing for detailed observation of the companion star during this period. One of the best such candidates is V404 Cyg.

Quiescence and advection-dominated accretion flow

The faintness of the accretion disc during quiescence is suspected to be caused by the flow entering a mode called an advection-dominated accretion flow (ADAF). In this mode, almost all the energy generated by friction in the disc is swept along with the flow instead of radiated away. If this model is correct, then it forms strong qualitative evidence for the presence of an event horizon.[104] Because, if the object at the center of the disc had a solid surface, it would emit large amounts of radiation as the highly energetic gas hits the surface, an effect that is observed for neutron stars in a similar state.[97]

Quasi-periodic oscillations

The X-ray emission from accretion disks sometimes flickers at certain frequencies. These signals are called quasi-periodic oscillations and are thought to be caused by material moving along the inner edge of the accretion disk (the innermost stable circular orbit). As such their frequency is linked to the mass of the compact object. They can thus be used as an alternative way to determine the mass of potential black holes.[105]

Galactic nuclei

Astronomers use the term "active galaxy" to describe galaxies with unusual characteristics, such as unusual spectral line emission and very strong radio emission. Theoretical and observational studies have shown that the activity in these active galactic nuclei (AGN) may be explained by the presence of supermassive black holes, which can be millions of time more massive than stellar ones. The models of these AGN consist of a central black hole that may be millions or billions of times more massive than the Sun; a disk of gas and dust called an accretion disk; and two jets that are perpendicular to the accretion disk.[106][107]

Although supermassive black holes are expected to be found in most AGN, only some galaxies' nuclei have been more carefully studied in attempts to both identify and measure the actual masses of the central supermassive black hole candidates. Some of the most notable galaxies with supermassive black hole candidates include the Andromeda Galaxy, M32, M87, NGC 3115, NGC 3377, NGC 4258, NGC 4889, NGC 1277, OJ 287, APM 08279+5255 and the Sombrero Galaxy.[109]

It is now widely accepted that the center of nearly every galaxy, not just active ones, contains a supermassive black hole.[110] The close observational correlation between the mass of this hole and the velocity dispersion of the host galaxy's bulge, known as the M-sigma relation, strongly suggests a connection between the formation of the black hole and the galaxy itself.[111]

Currently, the best evidence for a supermassive black hole comes from studying the proper motion of stars near the center of our own Milky Way.[113] Since 1995 astronomers have tracked the motion of 90 stars in a region called Sagittarius A*. By fitting their motion to Keplerian orbits they were able to infer in 1998 that 2.6 million M☉ must be contained in a volume with a radius of 0.02 lightyears.[114] Since then one of the stars—called S2—has completed a full orbit. From the orbital data they were able to place better constraints on the mass and size of the object causing the orbital motion of stars in the Sagittarius A* region, finding that there is a spherical mass of 4.3 million M☉ contained within a radius of less than 0.002 lightyears.[113] While this is more than 3000 times the Schwarzschild radius corresponding to that mass, it is at least consistent with the central object being a supermassive black hole, and no "realistic cluster [of stars] is physically tenable".[114]

Effects of strong gravity

Another way that the black hole nature of an object may be tested in the future is through observation of effects caused by strong gravity in their vicinity. One such effect is gravitational lensing: The deformation of spacetime around a massive object causes light rays to be deflected much like light passing through an optic lens. Observations have been made of weak gravitational lensing, in which light rays are deflected by only a few arcseconds. However, it has never been directly observed for a black hole.[115] One possibility for observing gravitational lensing by a black hole would be to observe stars in orbit around the black hole. There are several candidates for such an observation in orbit around Sagittarius A*.[115]

Another option would be the direct observation of gravitational waves produced by an object falling into a black hole, for example a compact object falling into a supermassive black hole through an extreme mass ratio inspiral. Matching the observed waveform to the predictions of general relativity would allow precision measurements of the mass and angular momentum of the central object, while at the same time testing general relativity.[116] These types of events are a primary target for the proposed Laser Interferometer Space Antenna.

Alternatives

The evidence for stellar black holes strongly relies on the existence of an upper limit for the mass of a neutron star. The size of this limit heavily depends on the assumptions made about the properties of dense matter. New exotic phases of matter could push up this bound.[98] A phase of free quarks at high density might allow the existence of dense quark stars,[117] and some supersymmetric models predict the existence of Q stars.[118] Some extensions of the standard model posit the existence of preons as fundamental building blocks of quarks and leptons, which could hypothetically form preon stars.[119] These hypothetical models could potentially explain a number of observations of stellar black hole candidates. However, it can be shown from general arguments in general relativity that any such object will have a maximum mass.[98]

Since the average density of a black hole inside its Schwarzschild radius is inversely proportional to the square of its mass, supermassive black holes are much less dense than stellar black holes (the average density of a 108 M☉ black hole is comparable to that of water).[98] Consequently, the physics of matter forming a supermassive black hole is much better understood and the possible alternative explanations for supermassive black hole observations are much more mundane. For example, a supermassive black hole could be modelled by a large cluster of very dark objects. However, such alternatives are typically not stable enough to explain the supermassive black hole candidates.[98]

The evidence for stellar and supermassive black holes implies that in order for black holes not to form, general relativity must fail as a theory of gravity, perhaps due to the onset of quantum mechanical corrections. A much anticipated feature of a theory of quantum gravity is that it will not feature singularities or event horizons (and thus no black holes).[120] In 2002,[121] much attention has been drawn by the fuzzball model in string theory. Based on calculations in specific situations in string theory, the proposal suggests that generically the individual states of a black hole solution do not have an event horizon or singularity, but that for a classical/semi-classical observer the statistical average of such states does appear just like an ordinary black hole in general relativity.[122]

Open questions

Entropy and thermodynamics

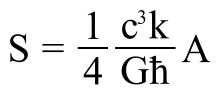

In 1971, Hawking showed under general conditions[Note 3] that the total area of the event horizons of any collection of classical black holes can never decrease, even if they collide and merge.[123] This result, now known as the second law of black hole mechanics, is remarkably similar to the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the total entropy of a system can never decrease. As with classical objects at absolute zero temperature, it was assumed that black holes had zero entropy. If this were the case, the second law of thermodynamics would be violated by entropy-laden matter entering a black hole, resulting in a decrease of the total entropy of the universe. Therefore, Bekenstein proposed that a black hole should have an entropy, and that it should be proportional to its horizon area.[124]

The link with the laws of thermodynamics was further strengthened by Hawking's discovery that quantum field theory predicts that a black hole radiates blackbody radiation at a constant temperature. This seemingly causes a violation of the second law of black hole mechanics, since the radiation will carry away energy from the black hole causing it to shrink. The radiation, however also carries away entropy, and it can be proven under general assumptions that the sum of the entropy of the matter surrounding a black hole and one quarter of the area of the horizon as measured in Planck units is in fact always increasing. This allows the formulation of the first law of black hole mechanics as an analogue of the first law of thermodynamics, with the mass acting as energy, the surface gravity as temperature and the area as entropy.[124]

One puzzling feature is that the entropy of a black hole scales with its area rather than with its volume, since entropy is normally an extensive quantity that scales linearly with the volume of the system. This odd property led Gerard 't Hooft and Leonard Susskind to propose the holographic principle, which suggests that anything that happens in a volume of spacetime can be described by data on the boundary of that volume.[125]

Although general relativity can be used to perform a semi-classical calculation of black hole entropy, this situation is theoretically unsatisfying. In statistical mechanics, entropy is understood as counting the number of microscopic configurations of a system that have the same macroscopic qualities (such as mass, charge, pressure, etc.). Without a satisfactory theory of quantum gravity, one cannot perform such a computation for black holes. Some progress has been made in various approaches to quantum gravity. In 1995, Andrew Strominger and Cumrun Vafa showed that counting the microstates of a specific supersymmetric black hole in string theory reproduced the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy.[126] Since then, similar results have been reported for different black holes both in string theory and in other approaches to quantum gravity like loop quantum gravity.[127]

Information loss paradox

| Is physical information lost in black holes? |

Because a black hole has only a few internal parameters, most of the information about the matter that went into forming the black hole is lost. Regardless of the type of matter which goes into a black hole, it appears that only information concerning the total mass, charge, and angular momentum are conserved. As long as black holes were thought to persist forever this information loss is not that problematic, as the information can be thought of as existing inside the black hole, inaccessible from the outside. However, black holes slowly evaporate by emitting Hawking radiation. This radiation does not appear to carry any additional information about the matter that formed the black hole, meaning that this information appears to be gone forever.[128]

The question whether information is truly lost in black holes (the black hole information paradox) has divided the theoretical physics community (see Thorne–Hawking–Preskill bet). In quantum mechanics, loss of information corresponds to the violation of vital property called unitarity, which has to do with the conservation of probability. It has been argued that loss of unitarity would also imply violation of conservation of energy.[129] Over recent years evidence has been building that indeed information and unitarity are preserved in a full quantum gravitational treatment of the problem.[130]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The set of possible paths, or more accurately the future light cone containing all possible world lines (in this diagram represented by the yellow/blue grid), is tilted in this way in Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates (the diagram is a "cartoon" version of an Eddington–Finkelstein coordinate diagram), but in other coordinates the light cones are not tilted in this way, for example in Schwarzschild coordinates they simply narrow without tilting as one approaches the event horizon, and in Kruskal–Szekeres coordinates the light cones don't change shape or orientation at all.[45]

- ↑ This is true only for 4-dimensional spacetimes. In higher dimensions more complicated horizon topologies like a black ring are possible.[52][53]

- ↑ In particular, he assumed that all matter satisfies the weak energy condition.

References

- ↑ Wald 1984, pp. 299–300

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wald, R. M. (1997). "Gravitational Collapse and Cosmic Censorship". arXiv:gr-qc/9710068 [gr-qc].

- ↑ Schutz, Bernard F. (2003). Gravity from the ground up. Cambridge University Press. p. 110. ISBN 0-521-45506-5.

- ↑ Davies, P. C. W. (1978). "Thermodynamics of Black Holes" (PDF). Reports on Progress in Physics 41 (8): 1313–1355. Bibcode:1978RPPh...41.1313D. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/41/8/004.

- ↑ O. Straub, F.H. Vincent, M.A. Abramowicz, E. Gourgoulhon, T. Paumard, ``Modelling the black hole silhouette in Sgr A* with ion tori,Astron. Astroph 543 (2012) A8

- ↑ Michell, J. (1784). "On the Means of Discovering the Distance, Magnitude, &c. of the Fixed Stars, in Consequence of the Diminution of the Velocity of Their Light, in Case Such a Diminution Should be Found to Take Place in any of Them, and Such Other Data Should be Procured from Observations, as Would be Farther Necessary for That Purpose". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 74 (0): 35–57. Bibcode:1784RSPT...74...35M. doi:10.1098/rstl.1784.0008. JSTOR 106576.

- ↑ Gillispie, C. C. (2000). Pierre-Simon Laplace, 1749–1827: a life in exact science. Princeton paperbacks. Princeton University Press. p. 175. ISBN 0-691-05027-9.

- ↑ Israel, W. (1989). "Dark stars: the evolution of an idea". In Hawking, S. W.; Israel, W. 300 Years of Gravitation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37976-2.

- ↑ Thorne 1994, pp. 123–124

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Schwarzschild, K. (1916). "Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einsteinschen Theorie". Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 7: 189–196. and Schwarzschild, K. (1916). "Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Kugel aus inkompressibler Flüssigkeit nach der Einsteinschen Theorie". Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 18: 424–434.

- ↑ Droste, J. (1917). "On the field of a single centre in Einstein's theory of gravitation, and the motion of a particle in that field" (PDF). Proceedings Royal Academy Amsterdam 19 (1): 197–215.

- ↑ Kox, A. J. (1992). "General Relativity in the Netherlands: 1915–1920". In Eisenstaedt, J.; Kox, A. J. Studies in the history of general relativity. Birkhäuser. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8176-3479-7.

- ↑ 't Hooft, G. (2009). "Introduction to the Theory of Black Holes" (PDF). Institute for Theoretical Physics / Spinoza Institute. pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Venkataraman, G. (1992). Chandrasekhar and his limit. Universities Press. p. 89. ISBN 81-7371-035-X.

- ↑ Detweiler, S. (1981). "Resource letter BH-1: Black holes". American Journal of Physics 49 (5): 394–400. Bibcode:1981AmJPh..49..394D. doi:10.1119/1.12686.

- ↑ Harpaz, A. (1994). Stellar evolution. A K Peters. p. 105. ISBN 1-56881-012-1.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Oppenheimer, J. R.; Volkoff, G. M. (1939). "On Massive Neutron Cores". Physical Review 55 (4): 374–381. Bibcode:1939PhRv...55..374O. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.55.374.

- ↑ Ruffini, R.; Wheeler, J. A. (1971). "Introducing the black hole" (PDF). Physics Today 24 (1): 30–41. Bibcode:1971PhT....24a..30R. doi:10.1063/1.3022513.

- ↑ Finkelstein, D. (1958). "Past-Future Asymmetry of the Gravitational Field of a Point Particle". Physical Review 110 (4): 965–967. Bibcode:1958PhRv..110..965F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.110.965.

- ↑ Kruskal, M. (1960). "Maximal Extension of Schwarzschild Metric". Physical Review 119 (5): 1743. Bibcode:1960PhRv..119.1743K. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.119.1743.

- ↑ Hewish, A. et al. (1968). "Observation of a Rapidly Pulsating Radio Source". Nature 217 (5130): 709–713. Bibcode:1968Natur.217..709H. doi:10.1038/217709a0

- ↑ Pilkington, J. D. H. et al. (1968). "Observations of some further Pulsed Radio Sources". Nature 218 (5137): 126–129. Bibcode:1968Natur.218..126P. doi:10.1038/218126a0

- ↑ Hewish, A. (1970). "Pulsars". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 8 (1): 265–296. Bibcode:1970ARA&A...8..265H. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.08.090170.001405.

- ↑ Newman, E. T. et al. (1965). "Metric of a Rotating, Charged Mass". Journal of Mathematical Physics 6 (6): 918. Bibcode:1965JMP.....6..918N. doi:10.1063/1.1704351

- ↑ Israel, W. (1967). "Event Horizons in Static Vacuum Space-Times". Physical Review 164 (5): 1776. Bibcode:1967PhRv..164.1776I. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.164.1776.

- ↑ Carter, B. (1971). "Axisymmetric Black Hole Has Only Two Degrees of Freedom". Physical Review Letters 26 (6): 331. Bibcode:1971PhRvL..26..331C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.26.331.

- ↑ Carter, B. (1977). "The vacuum black hole uniqueness theorem and its conceivable generalisations". Proceedings of the 1st Marcel Grossmann meeting on general relativity. pp. 243–254.

- ↑ Robinson, D. (1975). "Uniqueness of the Kerr Black Hole". Physical Review Letters 34 (14): 905. Bibcode:1975PhRvL..34..905R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.34.905.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Heusler, M. (1998). "Stationary Black Holes: Uniqueness and Beyond". Living Reviews in Relativity 1 (6). doi:10.12942/lrr-1998-6. Archived from the original on 1999-02-03. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Penrose, R. (1965). "Gravitational Collapse and Space-Time Singularities". Physical Review Letters 14 (3): 57. Bibcode:1965PhRvL..14...57P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.14.57.

- ↑ Ford, L. H. (2003). "The Classical Singularity Theorems and Their Quantum Loopholes". International Journal of Theoretical Physics 42 (6): 1219. doi:10.1023/A:1025754515197.

- ↑ Bardeen, J. M.; Carter, B.; Hawking, S. W. (1973). "The four laws of black hole mechanics". Communications in Mathematical Physics 31 (2): 161–170. Bibcode:1973CMaPh..31..161B. doi:10.1007/BF01645742. MR MR0334798. Zbl 1125.83309.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Hawking, S. W. (1974). "Black hole explosions?". Nature 248 (5443): 30–31. Bibcode:1974Natur.248...30H. doi:10.1038/248030a0.

- ↑ Quinion, M. (26 April 2008). "Black Hole". World Wide Words. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ↑ Carroll 2004, p. 253

- ↑ Thorne, K. S.; Price, R. H. (1986). Black holes: the membrane paradigm. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03770-8.

- ↑ Anderson, Warren G. (1996). "The Black Hole Information Loss Problem". Usenet Physics FAQ. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ↑ Preskill, J. (1994-10-21). Black holes and information: A crisis in quantum physics (PDF). Caltech Theory Seminar.

- ↑ Hawking & Ellis 1973, Appendix B

- ↑ Seeds, Michael A.; Backman, Dana E. (2007). Perspectives on Astronomy. Cengage Learning. p. 167. ISBN 0-495-11352-2

- ↑ Shapiro, S. L.; Teukolsky, S. A. (1983). Black holes, white dwarfs, and neutron stars: the physics of compact objects. John Wiley and Sons. p. 357. ISBN 0-471-87316-0.

- ↑ Berger, B. K. (2002). "Numerical Approaches to Spacetime Singularities". Living Reviews in Relativity 5: 1. arXiv:gr-qc/0201056. Bibcode:2002LRR.....5....1B. doi:10.12942/lrr-2002-1. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ↑ McClintock, J. E.; Shafee, R.; Narayan, R.; Remillard, R. A.; Davis, S. W.; Li, L.-X. (2006). "The Spin of the Near-Extreme Kerr Black Hole GRS 1915+105". Astrophysical Journal 652 (1): 518–539. arXiv:astro-ph/0606076. Bibcode:2006ApJ...652..518M. doi:10.1086/508457.

- ↑ Wald 1984, pp. 124–125

- ↑ Thorne, Misner & Wheeler 1973, p. 848

- ↑ Wheeler 2007, p. 179

- ↑ Carroll 2004, Ch. 5.4 and 7.3

- ↑ Carroll 2004, p. 217

- ↑ Carroll 2004, p. 218

- ↑ "Inside a black hole". Knowing the universe and its secrets. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ Carroll 2004, p. 222

- ↑ Emparan, R.; Reall, H. S. (2008). "Black Holes in Higher Dimensions". Living Reviews in Relativity 11 (6). arXiv:0801.3471. Bibcode:2008LRR....11....6E. doi:10.12942/lrr-2008-6. Retrieved 2011-02-10.

- ↑ Obers, N. A. (2009). Papantonopoulos, Eleftherios, ed. "Black Holes in Higher-Dimensional Gravity". Lecture Notes in Physics. Lecture Notes in Physics 769: 211–258. arXiv:0802.0519. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-88460-6. ISBN 978-3-540-88459-0.

- ↑ hawking & ellis 1973, Ch. 9.3

- ↑ Carroll 2004, p. 205

- ↑ Carroll 2004, pp. 264–265

- ↑ Carroll 2004, p. 252

- ↑ Lewis, G. F.; Kwan, J. (2007). "No Way Back: Maximizing Survival Time Below the Schwarzschild Event Horizon". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia 24 (2): 46–52. arXiv:0705.1029. Bibcode:2007PASA...24...46L. doi:10.1071/AS07012.

- ↑ Wheeler 2007, p. 182

- ↑ Carroll 2004, pp. 257–259 and 265–266

- ↑ Droz, S.; Israel, W.; Morsink, S. M. (1996). "Black holes: the inside story". Physics World 9 (1): 34–37. Bibcode:1996PhyW....9...34D.

- ↑ Carroll 2004, p. 266

- ↑ Poisson, E.; Israel, W. (1990). "Internal structure of black holes". Physical Review D 41 (6): 1796. Bibcode:1990PhRvD..41.1796P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.41.1796.

- ↑ Wald 1984, p. 212

- ↑ Hamade, R. (1996). "Black Holes and Quantum Gravity". Cambridge Relativity and Cosmology. University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ Palmer, D. "Ask an Astrophysicist: Quantum Gravity and Black Holes". NASA. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Nitta, Daisuke; Chiba, Takeshi; Sugiyama, Naoshi (September 2011). "Shadows of colliding black holes". Physical Review D 84 (6). arXiv:1106.2425. Bibcode:2011PhRvD..84f3008N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.84.063008

- ↑ Nemiroff, R. J. (1993). "Visual distortions near a neutron star and black hole". American Journal of Physics 61 (7): 619. arXiv:astro-ph/9312003. Bibcode:1993AmJPh..61..619N. doi:10.1119/1.17224.

- ↑ Carroll 2004, Ch. 6.6

- ↑ Carroll 2004, Ch. 6.7

- ↑ Einstein, A. (1939). "On A Stationary System With Spherical Symmetry Consisting of Many Gravitating Masses". Annals of Mathematics 40 (4): 922–936. doi:10.2307/1968902. JSTOR 1968902.

- ↑ Kerr, R. P. (2009). "The Kerr and Kerr-Schild metrics". In Wiltshire, D. L.; Visser, M.; Scott, S. M. The Kerr Spacetime. Cambridge University Press. arXiv:0706.1109. ISBN 978-0-521-88512-6.

- ↑ Hawking, S. W.; Penrose, R. (January 1970). "The Singularities of Gravitational Collapse and Cosmology". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 314 (1519): 529–548. Bibcode:1970RSPSA.314..529H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1970.0021. JSTOR 2416467.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 Carroll 2004, Section 5.8

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 Rees, M. J.; Volonteri, M. (2007). "Massive black holes: formation and evolution". In Karas, V.; Matt, G. Black Holes from Stars to Galaxies—Across the Range of Masses. Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–58. arXiv:astro-ph/0701512. ISBN 978-0-521-86347-6.

- ↑ Penrose, R. (2002). "Gravitational Collapse: The Role of General Relativity" (PDF). General Relativity and Gravitation 34 (7): 1141. Bibcode:2002GReGr..34.1141P. doi:10.1023/A:1016578408204.

- ↑ Carr, B. J. (2005). "Primordial Black Holes: Do They Exist and Are They Useful?". In Suzuki, H.; Yokoyama, J.; Suto, Y.; Sato, K. Inflating Horizon of Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology. Universal Academy Press. arXiv:astro-ph/0511743. ISBN 4-946443-94-0.

- ↑ Giddings, S. B.; Thomas, S. (2002). "High energy colliders as black hole factories: The end of short distance physics". Physical Review D 65 (5): 056010. arXiv:hep-ph/0106219. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..65e6010G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.056010.

- ↑ Harada, T. (2006). "Is there a black hole minimum mass?". Physical Review D 74 (8): 084004. arXiv:gr-qc/0609055. Bibcode:2006PhRvD..74h4004H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.74.084004.

- ↑ Arkani–Hamed, N.; Dimopoulos, S.; Dvali, G. (1998). "The hierarchy problem and new dimensions at a millimeter". Physics Letters B 429 (3–4): 263. arXiv:hep-ph/9803315. Bibcode:1998PhLB..429..263A. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(98)00466-3.

- ↑ LHC Safety Assessment Group. "Review of the Safety of LHC Collisions" (PDF). CERN.

- ↑ Cavaglià, M. (2010). "Particle accelerators as black hole factories?". Einstein-Online (Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute)) 4: 1010.

- ↑ Vesperini, E.; McMillan, S. L. W.; d'Ercole, A. et al. (2010). "Intermediate-Mass Black Holes in Early Globular Clusters". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 713 (1): L41–L44. arXiv:1003.3470. Bibcode:2010ApJ...713L..41V. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/713/1/L41.

- ↑ Zwart, S. F. P.; Baumgardt, H.; Hut, P. et al. (2004). "Formation of massive black holes through runaway collisions in dense young star clusters". Nature 428 (6984): 724–6. arXiv:astro-ph/0402622. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..724P. doi:10.1038/nature02448. PMID 15085124.

- ↑ O'Leary, R. M.; Rasio, F. A.; Fregeau, J. M. et al. (2006). "Binary Mergers and Growth of Black Holes in Dense Star Clusters". The Astrophysical Journal 637 (2): 937. arXiv:astro-ph/0508224. Bibcode:2006ApJ...637..937O. doi:10.1086/498446.

- ↑ Page, D. N. (2005). "Hawking radiation and black hole thermodynamics". New Journal of Physics 7: 203. arXiv:hep-th/0409024. Bibcode:2005NJPh....7..203P. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/7/1/203.

- ↑ Carroll 2004, Ch. 9.6

- ↑ "Evaporating black holes?". Einstein online. Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics. 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ↑ Giddings, S. B.; Mangano, M. L. (2008). "Astrophysical implications of hypothetical stable TeV-scale black holes". Physical Review D 78 (3): 035009. arXiv:0806.3381. Bibcode:2008PhRvD..78c5009G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.78.035009.

- ↑ Peskin, M. E. (2008). "The end of the world at the Large Hadron Collider?". Physics 1: 14. Bibcode:2008PhyOJ...1...14P. doi:10.1103/Physics.1.14.

- ↑ "Ripped Apart by a Black Hole". ESO Press Release. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Fichtel, C. E.; Bertsch, D. L.; Dingus, B. L. et al. (1994). "Search of the energetic gamma-ray experiment telescope (EGRET) data for high-energy gamma-ray microsecond bursts". Astrophysical Journal 434 (2): 557–559. Bibcode:1994ApJ...434..557F. doi:10.1086/174758.

- ↑ Naeye, R. "Testing Fundamental Physics". NASA. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "Event Horizon Telescope". MIT Haystack Observatory. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 "NASA's NuSTAR Sees Rare Blurring of Black Hole Light". NASA. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ "Short-cut method of solution of geodesic equations for Schwarzchild black hole", J.A. Marck, Class.Quant. Grav. 13 (1996) 393-402.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 McClintock, J. E.; Remillard, R. A. (2006). "Black Hole Binaries". In Lewin, W.; van der Klis, M. Compact Stellar X-ray Sources. Cambridge University Press. arXiv:astro-ph/0306213. ISBN 0-521-82659-4. section 4.1.5.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 98.3 98.4 98.5 98.6 98.7 98.8 Celotti, A.; Miller, J. C.; Sciama, D. W. (1999). "Astrophysical evidence for the existence of black holes". Classical and Quantum Gravity 16 (12A): A3–A21. arXiv:astro-ph/9912186. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/16/12A/301.

- ↑ Winter, L. M.; Mushotzky, R. F.; Reynolds, C. S. (2006). "XMM‐Newton Archival Study of the Ultraluminous X‐Ray Population in Nearby Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal 649 (2): 730. arXiv:astro-ph/0512480. Bibcode:2006ApJ...649..730W. doi:10.1086/506579.

- ↑ Bolton, C. T. (1972). "Identification of Cygnus X-1 with HDE 226868". Nature 235 (5336): 271–273. Bibcode:1972Natur.235..271B. doi:10.1038/235271b0.

- ↑ Webster, B. L.; Murdin, P. (1972). "Cygnus X-1—a Spectroscopic Binary with a Heavy Companion ?". Nature 235 (5332): 37–38. Bibcode:1972Natur.235...37W. doi:10.1038/235037a0.

- ↑ Rolston, B. (10 November 1997). "The First Black Hole". The bulletin. University of Toronto. Archived from the original on 2008-05-02. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ↑ Shipman, H. L.; Yu, Z; Du, Y.W (1 January 1975). "The implausible history of triple star models for Cygnus X-1 Evidence for a black hole". Astrophysical Letters 16 (1): 9–12. Bibcode:1975ApL....16....9S. doi:10.1016/S0304-8853(99)00384-4.

- ↑ Narayan, R.; McClintock, J. (2008). "Advection-dominated accretion and the black hole event horizon". New Astronomy Reviews 51 (10–12): 733. arXiv:0803.0322. Bibcode:2008NewAR..51..733N. doi:10.1016/j.newar.2008.03.002.

- ↑ "NASA scientists identify smallest known black hole" (Press release). Goddard Space Flight Center. 2008-04-01. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ↑ Krolik, J. H. (1999). Active Galactic Nuclei. Princeton University Press. Ch. 1.2. ISBN 0-691-01151-6.

- ↑ Sparke, L. S.; Gallagher, J. S. (2000). Galaxies in the Universe: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. Ch. 9.1. ISBN 0-521-59740-4.

- ↑ Chou, Felicia; Anderson, Janet; Watzke, Megan (5 January 2015). "RELEASE 15-001 - NASA’s Chandra Detects Record-Breaking Outburst from Milky Way’s Black Hole". NASA. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ Kormendy, J.; Richstone, D. (1995). "Inward Bound—The Search For Supermassive Black Holes In Galactic Nuclei". Annual Reviews of Astronomy and Astrophysics 33 (1): 581–624. Bibcode:1995ARA&A..33..581K. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.33.090195.003053.

- ↑ King, A. (2003). "Black Holes, Galaxy Formation, and the MBH-σ Relation". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 596 (1): 27–29. arXiv:astro-ph/0308342. Bibcode:2003ApJ...596L..27K. doi:10.1086/379143.

- ↑ Ferrarese, L.; Merritt, D. (2000). "A Fundamental Relation Between Supermassive Black Holes and their Host Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 539 (1): 9–12. arXiv:astro-ph/0006053. Bibcode:2000ApJ...539L...9F. doi:10.1086/312838.

- ↑ "A Black Hole's Dinner is Fast Approaching". ESO Press Release. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 Gillessen, S.; Eisenhauer, F.; Trippe, S. et al. (2009). "Monitoring Stellar Orbits around the Massive Black Hole in the Galactic Center". The Astrophysical Journal 692 (2): 1075. arXiv:0810.4674. Bibcode:2009ApJ...692.1075G. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/692/2/1075.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 Ghez, A. M.; Klein, B. L.; Morris, M. et al. (1998). "High Proper‐Motion Stars in the Vicinity of Sagittarius A*: Evidence for a Supermassive Black Hole at the Center of Our Galaxy". The Astrophysical Journal 509 (2): 678. arXiv:astro-ph/9807210. Bibcode:1998ApJ...509..678G. doi:10.1086/306528.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Bozza, V. (2010). "Gravitational Lensing by Black Holes". General Relativity and Gravitation 42 (42): 2269–2300. arXiv:0911.2187. Bibcode:2010GReGr..42.2269B. doi:10.1007/s10714-010-0988-2.

- ↑ Barack, L.; Cutler, C. (2004). "LISA capture sources: Approximate waveforms, signal-to-noise ratios, and parameter estimation accuracy". Physical Review D 69 (69): 082005. arXiv:gr-qc/0310125. Bibcode:2004PhRvD..69h2005B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.69.082005.

- ↑ Kovacs, Z.; Cheng, K. S.; Harko, T. (2009). "Can stellar mass black holes be quark stars?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 400 (3): 1632–1642. arXiv:0908.2672. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.400.1632K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15571.x.

- ↑ Kusenko, A. (2006). "Properties and signatures of supersymmetric Q-balls". arXiv:hep-ph/0612159.

- ↑ Hansson, J.; Sandin, F. (2005). "Preon stars: a new class of cosmic compact objects". Physics Letters B 616 (1–2): 1. arXiv:astro-ph/0410417. Bibcode:2005PhLB..616....1H. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2005.04.034.

- ↑ Kiefer, C. (2006). "Quantum gravity: general introduction and recent developments". Annalen der Physik 15 (1–2): 129. arXiv:gr-qc/0508120. Bibcode:2006AnP...518..129K. doi:10.1002/andp.200510175.

- ↑ "[NKS, Mathur states, 't Hooft-Polyakov monopoles, and Ward-Takahashi identities] - A New Kind of Science: The NKS Forum". wolframscience.com. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ Skenderis, K.; Taylor, M. (2008). "The fuzzball proposal for black holes". Physics Reports 467 (4–5): 117. arXiv:0804.0552. Bibcode:2008PhR...467..117S. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2008.08.001.

- ↑ Hawking, S. W. (1971). "Gravitational Radiation from Colliding Black Holes". Physical Review Letters 26 (21): 1344–1346. Bibcode:1971PhRvL..26.1344H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.26.1344.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Wald, R. M. (2001). "The Thermodynamics of Black Holes". Living Reviews in Relativity 4 (6): 12119. arXiv:gr-qc/9912119. Bibcode:1999gr.qc....12119W. doi:10.12942/lrr-2001-6. Retrieved 2011-02-10.

- ↑ 't Hooft, G. (2001). "The Holographic Principle". In Zichichi, A. Basics and highlights in fundamental physics. Subnuclear series 37. World Scientific. arXiv:hep-th/0003004. ISBN 978-981-02-4536-8.

- ↑ Strominger, A.; Vafa, C. (1996). "Microscopic origin of the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy". Physics Letters B 379 (1–4): 99. arXiv:hep-th/9601029. Bibcode:1996PhLB..379...99S. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(96)00345-0.

- ↑ Carlip, S. (2009). "Black Hole Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics". Lecture Notes in Physics. Lecture Notes in Physics 769: 89. arXiv:0807.4520. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-88460-6_3. ISBN 978-3-540-88459-0.

- ↑ Hawking, S. W. "Does God Play Dice?". www.hawking.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ↑ Giddings, S. B. (1995). "The black hole information paradox". Particles, Strings and Cosmology. Johns Hopkins Workshop on Current Problems in Particle Theory 19 and the PASCOS Interdisciplinary Symposium 5. arXiv:hep-th/9508151.

- ↑ Mathur, S. D. (2011). The information paradox: conflicts and resolutions. XXV International Symposium on Lepton Photon Interactions at High Energies. arXiv:1201.2079.

Further reading

- Popular reading

- Ferguson, Kitty (1991). Black Holes in Space-Time. Watts Franklin. ISBN 0-531-12524-6.

- Hawking, Stephen (1988). A Brief History of Time. Bantam Books, Inc. ISBN 0-553-38016-8.

- Hawking, Stephen; Penrose, Roger (1996). The Nature of Space and Time. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03791-4.

- Melia, Fulvio (2003). The Black Hole at the Center of Our Galaxy. Princeton U Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09505-9.

- Melia, Fulvio (2003). The Edge of Infinity. Supermassive Black Holes in the Universe. Cambridge U Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81405-8.

- Pickover, Clifford (1998). Black Holes: A Traveler's Guide. Wiley, John & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-19704-1.

- Thorne, Kip S. (1994). Black Holes and Time Warps. Norton, W. W. & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-31276-3.

- Wheeler, J. Craig (2007). Cosmic Catastrophes (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85714-7.

- University textbooks and monographs

- Carroll, Sean M. (2004). Spacetime and Geometry. Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-8053-8732-3., the lecture notes on which the book was based are available for free from Sean Carroll's website.

- Carter, B. (1973). "Black hole equilibrium states". In DeWitt, B. S.; DeWitt, C. Black Holes.

- Chandrasekhar, Subrahmanyan (1999). Mathematical Theory of Black Holes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850370-9.

- Frolov, V. P.; Novikov, I. D. (1998). "Black hole physics".

- Frolov, Valeri P.; Zelnikov, Andrei (2011). Introduction to Black Hole Physics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-969229-3. Zbl 1234.83001.

- Hawking, S. W.; Ellis, G. F. R. (1973). Large Scale Structure of space time. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09906-4.

- Melia, Fulvio (2007). The Galactic Supermassive Black Hole. Princeton U Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13129-0.

- Taylor, Edwin F.; Wheeler, John Archibald (2000). Exploring Black Holes. Addison Wesley Longman. ISBN 0-201-38423-X.

- Thorne, Kip S.; Misner, Charles; Wheeler, John (1973). Gravitation. W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- Wald, Robert M. (1984). General Relativity. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-87033-5.

- Wald, Robert M. (1992). Space, Time, and Gravity: The Theory of the Big Bang and Black Holes. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-87029-4.

- Review papers

- Gallo, Elena; Marolf, Donald (2009). "Resource Letter BH-2: Black Holes". American Journal of Physics 77 (4): 294. arXiv:0806.2316. Bibcode:2009AmJPh..77..294G. doi:10.1119/1.3056569.

- Hughes, Scott A. (2005). "Trust but verify: The case for astrophysical black holes". arXiv:hep-ph/0511217. Lecture notes from 2005 SLAC Summer Institute.

External links

- Black Holes on In Our Time at the BBC. (listen now)

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Singularities and Black Holes" by Erik Curiel and Peter Bokulich.

- "Black hole" on Scholarpedia.

- Black Holes: Gravity's Relentless Pull—Interactive multimedia Web site about the physics and astronomy of black holes from the Space Telescope Science Institute

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Black Holes

- "Schwarzschild Geometry"

- Advanced Mathematics of Black Hole Evaporation

- Hubble site

- Videos

- 16-year-long study tracks stars orbiting Milky Way black hole

- Movie of Black Hole Candidate from Max Planck Institute

- Nature.com 2015-04-20 3D simulations of colliding black holes

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||