Bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide

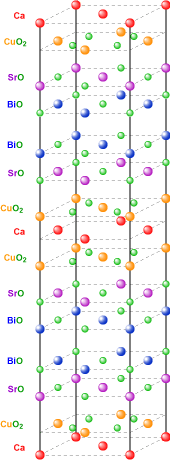

Bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide, or BSCCO (pronounced "bisko"), is a family of high-temperature superconductors having the generalized chemical formula Bi2Sr2Can-1CunO2n+4+x, with n=2 being the most commonly studied compound (though n=1 and n=3 have also received significant attention). Discovered as a general class in 1988,[1] BSCCO was the first high-temperature superconductor which did not contain a rare earth element. It is a cuprate superconductor, an important category of high-temperature superconductors sharing a two-dimensional layered (perovskite) structure (see figure at right) with superconductivity taking place in a copper oxide plane. BSCCO and YBCO are the most studied cuprate superconductors.

Specific types of BSCCO are usually referred to using the sequence of the numbers of the metallic ions. Thus Bi-2201 is the n=1 compound (Bi2Sr2CuO6+x), Bi-2212 is the n=2 compound (Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x) and Bi-2223 is the n=3 compound (Bi2Sr2Ca2Cu3O10+x).

The BSCCO family is analogous to a thallium family of high-temperature superconductors referred to as TBCCO and having the general formula Tl2Ba2Can-1CunO2n+4+x, and a mercury family HBCCO of formula HgBa2Can-1CunO2n+2+x. There are a number of other variants of these superconducting families. In general their critical temperature at which they become superconducting rises for the first few members then falls. Thus Bi-2201 has Tc ≈ 2 K, Bi-2212 has Tc ≈ 95 K, Bi-2223 has Tc ≈ 108 K, and Bi-2234 has Tc ≈ 104 K. This last member is very difficult to synthesize.

Discovery

BSCCO as a new class of superconductor was discovered around 1988 by Hiroshi Maeda and colleagues[1] at the National Research Institute for Metals in Japan, though at the time they were unable to determine its precise composition and structure. Almost immediately several groups, and most notably Subramanian[2] et al at Dupont and Cava[3] et al at AT&T Bell Labs, identified Bi-2212. The n=3 member proved quite elusive and was not identified until a month or so later by Tallon[4] et al in a government research lab in New Zealand. There have been only minor improvements to these materials since. A key early development was to replace about 15% of the Bi by Pb, which greatly accelerated the formation and quality of Bi-2223.

Properties

BSCCO needs to be hole-doped by an excess of oxygen atoms (δ in the formula) in order to superconduct. As in all high-temperature superconductors (HTS) Tc is sensitive to the exact doping level: the maximum Tc for Bi-2212 (as for most HTS) is achieved with an excess of about 0.16 holes per Cu atom.[5][6] This is referred to as optimum doping. Samples with lower doping (and hence lower Tc) are generally referred to as underdoped while those with excess doping (also lower Tc) are overdoped. By changing the oxygen content Tc can thus be altered at will. By many measures, overdoped HTS are strong superconductors, even if their Tc is less than optimum, but underdoped HTS become extremely weak. The application of external pressure generally raises Tc in underdoped samples to values that well exceed the maximum at ambient pressure. This is not fully understood though a secondary effect is that pressure increases the doping. Bi-2223 is complicated in that it has three distinct copper-oxygen planes. The two outer copper-oxygen layers are typically close to optimal doping while the remaining inner layer is markedly underdoped. Thus the application of pressure in Bi-2223 results in Tc rising to a maximum of about 123 K due to optimisation of the two outer planes. Following an extended decline, Tc then rises again towards 140 K due to optimisation of the inner plane. A key challenge therefore is to determine how to optimise all copper-oxygen layers simultaneously. Considerable improvements in superconducting properties could yet be achieved using such strategies.

BSCCO is a Type II superconductor. The upper critical field, Hc2, in Bi-2212 polycrystalline samples at 4.2 K has been measured as 200 ± 25 T (cf 168±26 T for YBCO polycrystalline samples).[7] In practice HTS are limited by the irreversibility field, H*, above which magnetic vortices melt or decouple. Even though BSCCO has a higher upper critical field than YBCO it has a much lower H* (typically smaller by a factor of 100)[8] thus limiting its use for making high-field magnets. It is for this reason that conductors of YBCO are preferred to BSCCO though they are much more difficult to fabricate.

Wires and tapes

BSCCO was the first HTS material to be used for making practical superconducting wires. All HTS have an extremely short coherence length, of the order of 1.6 nm. This means that the grains in a polycrystalline wire must be extremely good contact – they must be atomically smooth. Further, because the superconductivity resides substantially only in the copper-oxygen planes the grains must be crystallographically aligned. BSCCO is therefore a good candidate because its grains can be aligned either by melt processing or by mechanical deformation. The double bismuth oxide layer is only weakly bonded by van der Waals forces. So like graphite or mica, deformation causes slip on these BiO planes and grains tend to deform into aligned plates. Further, because BSCCO has n=1, 2 and 3 members these naturally tend to accommodate low angle grain boundaries so that indeed they remain atomically smooth. Thus first-generation HTS wires (referred to as 1G) have been manufactured for many years now by companies such as American Superconductor Corporation (AMSC) in the USA and Sumitomo in Japan – though AMSC has now abandoned BSCCO wire in favour of 2G wire based on YBCO.

Typically, precursor powders are packed into a silver tube which is extruded down in diameter. These are then repacked as multiple tubes in a silver tube and again extruded down in diameter, then drawn down further in size and rolled into a flat tape. The last step ensures grain alignment. The tapes are then reacted at high temperature to form dense, crystallographically aligned Bi-2223 multifilamentary conducting tape suitable for winding cables or coils for transformers, magnets, motors and generators.[9][10] Typical tapes of 4 mm width and 0.2 mm thickness support a current at 77 K of 200 A, giving a critical current density (maximal amperes per square metre of cross-sectional area) in the Bi-2223 filaments of 5×105 A/cm2. This rises markedly with decreasing temperature so that many applications are implemented at 30-35 K, even though Tc is 108 K.

Applications

- 1G conductors made from Bi-2223 multifilamentary tapes.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 H. Maeda, Y. Tanaka, M. Fukutumi, and T. Asano (1988). "A New High-Tc Oxide Superconductor without a Rare Earth Element". Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 27 (2): L209–L210. Bibcode:1988JaJAP..27L.209M. doi:10.1143/JJAP.27.L209.

- ↑ M. A. Subramanian et al. (1988). "A new high-temperature superconductor: Bi2Sr3-xCaxCu2O8+y". Science 239 (4843): 1015–1017. Bibcode:1988Sci...239.1015S. doi:10.1126/science.239.4843.1015. PMID 17815702.

- ↑ R. J. Cava et al. (1988). "Structure and physical properties of single crystals of the 84-K superconductor Bi2.2Sr2Ca0.8Cu2O8+δ". Physical Review B 38 (1): 893–896. Bibcode:1988PhRvB..38..893S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.38.893.

- ↑ J. L. Tallon et al. (1988). "High-Tc superconducting phases in the series Bi2.1(Ca,Sr)n+1CunO2n+4+δ". Nature 333 (6169): 153–156. Bibcode:1988Natur.333..153T. doi:10.1038/333153a0.

- ↑ M. R. Presland et al. (1991). "General trends in oxygen stoichiometry effects in Bi and Tl superconductors". Physica C 176 (1-3): 95. Bibcode:1991PhyC..176...95P. doi:10.1016/0921-4534(91)90700-9.

- ↑ J. L. Tallon et al. (1995). "Generic Superconducting Phase Behaviour in High-Tc Cuprates: Tc variation with hole concentration in YBa2Cu3O7-δ". Physical Review B 51 (18): (R)12911–4. Bibcode:1995PhRvB..5112911T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.51.12911.

- ↑ A. I. Golovashkin et al. (1991). "Low temperature direct measurements of Hc2 in HTSC using megagauss magnetic fields". Physica C: Superconductivity. 185-189: 1859. Bibcode:1991PhyC..185.1859G. doi:10.1016/0921-4534(91)91055-9.

- ↑ K. Togano et al. (1988). "Properties of Pb-doped Bi-Sr-Ca-Cu-O superconductors". Applied Physics Letters 53 (14): 1329–1331. Bibcode:1988ApPhL..53.1329T. doi:10.1063/1.100452.

- ↑ C.L. Briant, E.L. Hall, K.W. Lay, I.E. Tkaczyk (1994). "Microstructural evolution of the BSCCO-2223 during powder-in-tube processing". J. Mater. Res. 9 (11): 2789–2808. Bibcode:1994JMatR...9.2789B. doi:10.1557/JMR.1994.2789.

- ↑ Timothy P. Beales, Jo Jutson, Luc Le Lay and Michelé Mölgg (1997). "Comparison of the powder-in-tube processing properties of two (Bi2-xPbx)Sr2Ca2Cu3O10+δpowders". J. Mater. Chem. 7 (4): 653–659. doi:10.1039/a606896k.