Bioenergetic systems

Bioenergetic systems are metabolic processes which relate to the flow of energy in the living organisms. Those processes convert the energy into adenosine triphosphate, which is the form of chemical energy suitable for muscular activity. There are two main forms of synthesis of adenosine triphosphate: aerobic, which involves oxygen from the bloodstream, and anaerobic, which does not. Bioenergetics is the field of biology which studies the bioenergetic systems.

Overview

The cellular respiration process that converts food energy into adenosine triphosphate (a form of energy) is largely dependent on the availability of oxygen. During exercise, the supply and demand of oxygen available to muscle cells is affected by the duration and intensity of the exercise and by the individual's cardiorespiratory fitness level. There are three exercise energy systems that can be selectively recruited, depending on the amount of oxygen available, as part of the cellular respiration process to generate the ATP energy for the muscles. They are adenosine triphosphate, the anaerobic system and the aerobic system.

Adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is the usable form of chemical energy for muscular activity. It is stored in most cells, particularly in muscle cells. Other forms of chemical energy, such as those available from food, must be transferred into ATP form before they can be utilized by the muscle cells.[1]

The principle of coupled reactions

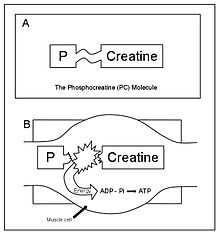

Since energy is released when ATP is broken down, energy is required to rebuild or resynthesize ATP. The building blocks of ATP synthesis are the by-products of its breakdown; adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). The energy for ATP resynthesis comes from three different series of chemical reactions that take place within the body. Two of the three depend upon the food we eat, whereas the other depends upon a chemical compound called phosphocreatine. The energy released from any of these three series of hi reactions is coupled with the energy needs of the reaction that resynthesizes ATP. The separate reactions are functionally linked together in such a way that the energy released by the one is always used by the other.[2]

There are three methods to resynthesize ATP:

- ATP–CP system (phosphogen system) – This system is used only for very short durations of up to 10 seconds. The ATP–CP system neither uses oxygen nor produces lactic acid if oxygen is unavailable and is thus said to be alactic anaerobic. This is the primary system behind very short, powerful movements like a golf swing, a 100 m sprint, or powerlifting.

- Anaerobic system – Predominates in supplying energy for exercises lasting less than two minutes. Also known as the glycolytic system. An example of an activity of the intensity and duration that this system works under would be a 400 m sprint.

- Aerobic system – This is the long-duration energy system. By five minutes of exercise, the O2 system is clearly the dominant system. In a 1 km run, this system is already providing approximately half the energy; in a marathon run it provides 98% or more.[3]

Aerobic and anaerobic metabolism

The term metabolism refers to the various series of chemical reactions that take place within the body. Aerobic refers to the presence of oxygen, whereas anaerobic means with series of chemical reactions that does not require the presence of oxygen. The ATP-CP series and the lactic acid series are anaerobic, whereas the oxygen series, is aerobic.[4]

ATP–CP: the phosphagen system

Creatine phosphate (CP), like ATP, is stored in the muscle cells. When it is broken down, a large amount of energy is released. The energy released is coupled to the energy requirement necessary for the resynthesis of ATP.

The total muscular stores of both ATP and CP are very small. Thus, the amount of energy obtainable through this system is limited. If an individual were to run 100 meters as fast as they could, the phosphagen stores in the working muscles would probably be exhausted by the end of the sprint, about 15–30 seconds later. However, the usefulness of the ATP-CP system lies in the rapid availability of energy rather than quantity. This is extremely important with respect to the kinds of physical activities that humans are capable of performing.[5]

Anaerobic system

This system is known as anaerobic glycolysis. “Glycolysis” refers to the breakdown of sugar. In this system, the breakdown of sugar supplies the necessary energy from which ATP is manufactured. When sugar is metabolized anaerobically, it is only partially broken down and one of the by-products is lactic acid. This process creates enough energy to couple with the energy requirements to resynthesize ATP.

When H+ ions accumulate in the muscles causing the blood pH level to reach very low levels, temporary muscular fatigue results. Another limitation of the lactic acid system that relates to its anaerobic quality is that only a few moles of ATP can be resynthesized from the breakdown of sugar as compared to the yield possible when oxygen is present. This system cannot be relied on for extended periods of time.

The lactic acid system, like the ATP-CP system, is extremely important, primarily because it also provides a rapid supply of ATP energy. For example, exercises that are performed at maximum rates for between 1 and 3 minutes depend heavily upon the lactic acid system for ATP energy. In activities such as running 1500 meters or a mile, the lactic acid system is used predominately for the “kick” at the end of a race.[6]

Aerobic system

- The Krebs cycle

- Oxidative phosphorylation

Glycolysis – The first stage is known as glycolysis, which produces 2 ATP molecules, 2 reduced molecules of NAD (NADH), and 2 pyruvate molecules which move on to the next stage – the Krebs cycle. Glycolysis takes place in the cytoplasm of normal body cells, or the sarcoplasm of muscle cells.

The Krebs cycle – This is the second stage, and the products of this stage of the aerobic system are a net production of one ATP, one carbon dioxide molecule, three reduced NAD molecules, one reduced FAD molecule (The molecules of NAD and FAD mentioned here are electron carriers, and if they are said to be reduced, this means that they have had a H+ ion added to them). The things produced here are for each turn of the Krebs cycle. The Krebs cycle turns twice for each molecule of glucose that passes through the aerobic system – as two pyruvate molecules enter the Krebs cycle. In order for the Pyruvate molecules to enter the Krebs cycle they must be converted to Acetyl Coenzyme A. During this link reaction, for each molecule of pyruvate that gets converted to Acetyl Coenzyme A, an NAD is also reduced. This stage of the aerobic system takes place in the matrix of the cells' mitochondria.

Oxidative phosphorylation – This is the last stage of the aerobic system and produces the largest yield of ATP out of all the stages – a total of 34 ATP molecules. It is called oxidative phosphorylation because oxygen is the final acceptor of the electrons and hydrogen ions that leave this stage of aerobic respiration (hence oxidative) and ADP gets phosphorylated (an extra phosphate gets added) to form ATP (hence phosphorylation).

This stage of the aerobic system occurs on the cristae (infoldings on the membrane of the mitochondria). The NADH+ from glycolysis and the Krebs cycle, and the FADH+ from the Krebs cycle pass down electron carriers which are at decreasing energy levels, in which energy is released to reform ATP. Each NADH+ that passes down this electron transport chain provides enough energy for 3 molecules of ATP, and each molecule of FADH+ provides enough energy for 2 molecules of ATP. If you do your math this means that 10 total NADH+ molecules allow the rejuvenation of 30 ATP, and 2 FADH+ molecules allow for 4 ATP molecules to be rejuvenated (The total being 34 from oxidative phosphorylation, plus the 4 from the previous 2 stages meaning a total of 38 ATP being produced during the aerobic system). The NADH+ and FADH+ get oxidized to allow the NAD and FAD to return to be used in the aerobic system again, and electrons and hydrogen ions are accepted by oxygen to produce water, a harmless by-product.

How they work

Aerobic and anaerobic systems usually work concurrently. When describing activity it is not which energy system is working but which predominates.[7]

References

- ↑ Fox, Edward (1979). Sports Physiology. United States of America: Saunders College Publishing. pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Fox, Edward (1979). Sports Phisiology. United States of America: Saunders College Publishing. pp. 8–9.

- ↑ James Madison University Strength and Conditioning Program (link is dead)

- ↑ Fox, Edward (1979). Sports Physiology. United States of America: Saunders College Publishing. p. 9.

- ↑ Fox, Edward (1979). Sports Physiology. United States of America: Saunders College Publishing. pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Fox, Edward (1979). Sports Physiology. United States of America: Saunders College Publishing. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Energy Proportion Graphs

Further reading

- Exercise Physiology for Health, Fitness and Performance. Sharon Plowman and Denise Smith. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Third edition (2010). ISBN 978-0-7817-7976-0.