Bio-MEMS

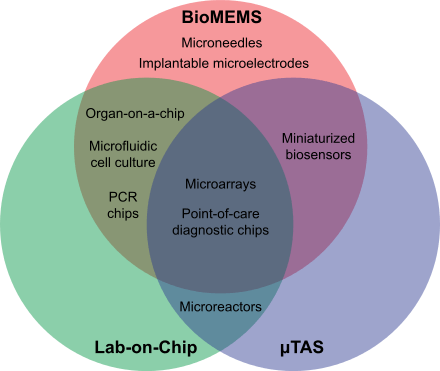

Bio-MEMS is an abbreviation for biomedical (or biological) microelectromechanical systems. Bio-MEMS have considerable overlap, and is sometimes considered synonymous, with lab-on-a-chip (LOC) and micro total analysis systems (μTAS). Bio-MEMS is typically more focused on mechanical parts and microfabrication technologies made suitable for biological applications. On the other hand, lab-on-a-chip is concerned with miniaturization and integration of laboratory processes and experiments into single (often microfluidic) chips. In this definition, lab-on-a-chip devices do not strictly have biological applications, although most do or are amendable to be adapted for biological purposes. Similarly, micro total analysis systems may not have biological applications in mind, and are usually dedicated to chemical analysis. A broad definition for bio-MEMS can be used to refer to the science and technology of operating at the microscale for biological and biomedical applications, which may or may not include any electronic or mechanical functions.[2] The interdisciplinary nature of bio-MEMS combines material sciences, clinical sciences, medicine, surgery, electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, optical engineering, chemical engineering, and biomedical engineering.[2] Some of its major applications include genomics, proteomics, molecular diagnostics, point-of-care diagnostics, tissue engineering, and implantable microdevices.[2]

History

In 1967, S. B. Carter reported the use of shadow-evaporated palladium islands for cell attachment.[3] After this first bio-MEMS study, subsequent development in the field was slow for around 20 years.[3] In 1985, Unipath Inc. commercialized ClearBlue, a pregnancy test still used today that can be considered the first microfluidic device containing paper and the first microfluidic product to market.[3] In 1990, Andreas Manz and H. Michael Widmer from Ciba-Geigy (now Novartis), Switzerland first coined the term micro total analysis system (μTAS) in their seminal paper proposing the use of miniaturized total chemical analysis systems for chemical sensing.[4] There have been three major motivating factors behind the concept of μTAS.[3] Firstly, drug discovery in the last decades leading up to the 1990s had been limited due to the time and cost of running many chromatographic analyses in parallel on macroscopic equipment.[3] Secondly, the Human Genome Project (HGP), which started in October 1990, created demand for improvements in DNA sequencing capacity.[3] Capillary electrophoresis thus became a focus for chemical and DNA separation.[3] Thirdly, DARPA of the US Department of Defense supported a series of microfluidic research programs in the 1990s after realizing there was a need to develop field-deployable microsystems for the detection of chemical and biological agents that were potential military and terrorist threats.[5] Researchers started to use photolithography equipment for microfabrication of microeletromechanical systems (MEMS) as inherited from the microelectronics industry.[3] At the time, the application of MEMS to biology was limited because this technology was optimized for silicon or glass wafers and used solvent-based photoresists that were not compatible with biological material.[3] In 1993, George M. Whitesides, a Harvard chemist, introduced inexpensive PDMS-based microfabrication and this revolutionized the bio-MEMS field.[3] Since then, the field of bio-MEMS has exploded. Selected major technical achievements during bio-MEMS development of the 1990s include:

- In 1991, the first oligonucleotide chip was developed[6]

- In 1998, the first solid microneedles were developed for drug delivery[7]

- In 1998, the first continuous-flow polymerase chain reaction chip was developed[8]

- In 1999, the first demonstration of heterogeneous laminar flows for selective treatment of cells in microchannels[9]

Today, hydrogels such as agarose, biocompatible photoresists, and self-assembly are key areas of research in improving bio-MEMS as replacements or complements to PDMS.[3]

Approaches

Materials

Silicon and glass

Conventional micromachining techniques such as wet etching, dry etching, deep reactive ion etching, sputtering, anodic bonding, and fusion bonding have been used in bio-MEMS to make flow channels, flow sensors, chemical detectors, separation capillaries, mixers, filters, pumps and valves.[10] However, there are some drawbacks to using silicon-based devices in biomedical applications such as their high cost and bioincompatibility.[10] Due to being single-use only, larger than their MEMS counterparts, and the requirement of clean room facilities, high material and processing costs make silicon-based bio-MEMS less economically attractive.[10] In vivo, silicon-based bio-MEMS can be readily functionalized to minimize protein adsorption, but the brittleness of silicon remains a major issue.[10]

Plastics and polymers

Using plastics and polymers in bio-MEMS is attractive because they can be easily fabricated, compatible with micromachining and rapid prototyping methods, as well as have low cost.[10][11] Many polymers are also optically transparent and can be integrated into systems that use optical detection techniques such as fluorescence, UV/Vis absorbance, or Raman method.[11] Moreover, many polymers are biologically compatible, chemically inert to solvents, and electrically insulating for applications where strong electrical fields are necessary such as electrophoretic separation.[10] Surface chemistry of polymers can also be modified for specific applications.[10] The most common polymers used in bio-MEMS include PMMA, PDMS, and SU-8.[10]

B) and C) Single fibroblasts are spatially constrained to the geometry of the fibronectin micropattern.[12]

Biological materials

Microscale manipulation and patterning of biological materials such as proteins, cells and tissues have been used in the development of cell-based arrays, microarrays, microfabrication based tissue engineering, and artificial organs.[11] Biological micropatterning can be used for high-throughput single cell analysis,[13] precise control of cellular microenvironment, as well as controlled integration of cells into appropriate multi-cellular architectures to recapitulate in vivo conditions.[14] Photolithography, microcontact printing, selective microfluidic delivery, and self-assembled monolayers are some methods used to pattern biological molecules onto surfaces.[3][14] Cell micropatterning can be done using microcontact patterning of extracellular matrix proteins, cellular electrophoresis, optical tweezer arrays, dielectrophoresis, and electrochemically active surfaces.[15]

Paper

Paper microfluidics (sometimes called lab on paper) is the use of paper substrates in microfabrication to manipulate fluid flow for different applications.[3][16] Paper microfluidics have been applied in paper electrophoresis and immunoassays, the most notable being the commercialized pregnancy test, ClearBlue.[3] Advantages of using paper for microfluidics and electrophoresis in bio-MEMS include its low cost, biodegradability, and natural wicking action.[3] Compared to traditional microfluidic channels, paper microchannels are accessible for sample introduction (especially forensic-style samples such as body fluids and soil), as well as its natural filtering properties that exclude cell debris, dirt, and other impurities in samples.[3] Techniques for micropatterning paper include photolithography, laser cutting, ink jet printing, plasma treatment, and wax patterning.[3][16]

Electrokinetics

Electrokinetics have been exploited in bio-MEMS for separating mixtures of molecules and cells using electrical fields. In electrophoresis, a charged species in a liquid moves under the influence of an applied electric field.[3] Electrophoresis has been used to fractionate small ions, charged organic molecules, proteins, and DNA.[3] Electrophoresis and microfluidics are highly synergistic because it is possible to use higher voltages in microchannels due to faster heat removal.[3] Isoelectric focusing is the separation of proteins, organelles, and cells with different isoelectric points.[3] Isoelectric focusing requires a pH gradient (usually generated with electrodes) perpendicular to the flow direction.[3] Sorting and focusing of the species of interest is achieved because an electrophoretic force causes perpendicular migration until it flows along its respective isoelectric points.[3] Dielectrophoresis is the motion of uncharged particles due to induced polarization from nonuniform electric fields. Dielectrophoresis can be used in bio-MEMS for dielectrophoresis traps, concentrating specific particles at specific points on surfaces, and diverting particles from one flow stream to another for dynamic concentration.[3]

Microfluidics

Microfluidics refers to systems that manipulate small (10−9 – 10−18 L) amounts of fluids on microfabricated substrates. Microfluidic approaches to bio-MEMS confer several advantages:

- Flow in microchannels is laminar, which allows selective treatment of cells in microchannels,[9] mathematical modelling of flow patterns and concentrations, as well as quantitative predictions of the biological environment of cells and biochemical reactions[3]

- Microfluidic features can be fabricated on the cellular scale or smaller, which enables investigation of (sub)cellular phenomena, seeding and sorting of single cells, and recapitulation of physiological parameters[3]

- Integration of microelectronics, micromechanics, and microoptics onto the same platform allows automated device control, which reduces human error and operation costs[3]

- Microfluidic technology is relatively economical due to batch fabrication and high-throughput (parallelization and redundancy). This allows the production of disposable or single-use chips for improved ease of use and reduced probability of biological cross contamination, as well as rapid prototyping[3][11]

- Microfluidic devices consume much smaller amounts of reagents, can be made to require only a small amount of analytes for chemical detection, require less time for processes and reactions to complete, and produces less waste than conventional macrofluidic devices and experiments[3]

- Appropriate packaging of microfluidic devices can make them suitable for wearable applications, implants, and portable applications in developing countries[3]

An interesting approach combining electrokinetic phenomena and microfluidics is digital microfluidics. In digital microfluidics, a substrate surface is micropatterned with electrodes and selectively activated.[3] Manipulation of small fluid droplets occurs via electrowetting, which is the phenomenon where an electric field changes the wettability of an electrolyte droplet on a surface.[3]

Bio-MEMS as Miniaturized Biosensors

Biosensors are devices that consist of a biological recognition system, called the bioreceptor, and a transducer.[19] The interaction of the analyte with the bioreceptor causes an effect that the transducer can convert into a measurement, such as an electrical signal.[19] The most common bioreceptors used in biosensing are based on antibody–antigen interactions, nucleic acid interactions, enzymatic interactions, cellular interactions, and interactions using biomimetic materials.[19] Common transducer techniques include mechanical detection, electrical detection, and optical detection.[11][19]

Micromechanical sensors

Mechanical detection in bio-MEMS is achieved through micro- and nano-scale cantilevers for stress sensing and mass sensing,[11] or micro- and nano-scale plates or membranes.[20] In stress sensing, the biochemical reaction is performed selectively on one side of the cantilever to cause a change in surface free energy.[11] This results in bending of the cantilever that is measurable either optically (laser reflection into a quadposition detector) or electrically (piezo-resistor at the fixed edge of the cantilever) due to a change in surface stress.[11] In mass sensing, the cantilever vibrates at its resonant frequency as measured electrically or optically.[11] When a biochemical reaction takes place and is captured on the cantilever, the mass of the cantilever changes, as does the resonant frequency.[11] Mass sensing is not as effective in fluids because the minimum detectable mass is much higher in damped mediums,[11] something that is overcome with plates or membranes.[20] The advantage of using cantilever sensors is that there is no need for an optically detectable label on the analyte or bioreceptors.[11]

Electrical and electrochemical sensors

Electrical and electrochemical detection are easily adapted for portability and miniaturization, especially in comparison to optical detection.[11] In amperometric biosensors, an enzyme-catalyzed redox reaction causes a redox electron current that is measured by a working electrode.[11] Amperometric biosensors have been used in bio-MEMS for detection of glucose, galactose, lactose, urea, and cholesterol, as well as for applications in gas detection and DNA hybridization.[11] In potentiometric biosensors, measurements of electric potential at one electrode are made in reference to another electrode.[11] Examples of potentiometric biosensors include ion-sensitive field effect transistors (ISFET), Chemical field-effect transistors (chem-FET), and light-addressable potentiometric sensors (LAPS).[11] In conductometric biosensors, changes in electrical impedance between two electrodes are measured as a result of a biomolecular reaction.[11] Conductive measurements are simple and easy to use because there is no need for a specific reference electrode, and have been used to detect biochemicals, toxins, nucleic acids, and bacterial cells.[11]

Optical sensors

A challenge in optical detection is the need for integrating detectors and photodiodes in a miniaturized portable format on the bio-MEMS.[11] Optical detection includes fluorescence-based techniques, chemiluminescence-based techniques, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Fluorescence-based optical techniques use markers that emit light at specific wavelengths and the presence or enhancement/reduction (e.g. fluorescence resonance energy transfer) in optical signal indicates a reaction has occurred.[11] Fluorescence-based detection has been used in microarrays and PCR on a chip devices.[11] Chemiluminescence is light generation by energy release from a chemical reaction.[11] Bioluminescence and electrochemiluminescence are subtypes of chemiluminescence.[11] Surface plasmon resonance sensors can be thin-film refractometers or gratings that measure the resonance behaviour of surface plasmon on metal or dielectric surfaces.[21] The resonance changes when biomolecules are captured or adsorbed on the sensor surface and depends on the concentration of the analyte as well as its properties.[21] Surface plasmon resonance has been used in food quality and safety analysis, medical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring.[21]

Bio-MEMS for diagnostics

Genomic and proteomic microarrays

The goals of genomic and proteomic microarrays are to make high-throughput genome analysis faster and cheaper, as well as identify activated genes and their sequences.[3] There are many different types of biological entities used in microarrays, but in general the microarray consists of an ordered collection of microspots each containing a single defined molecular species that interacts with the analyte for simultaneous testing of thousands of parameters in a single experiment.[22] Some applications of genomic and proteomic microarrays are neonatal screening, identifying disease risk, and predicting therapy efficacy for personalized medicine.

Oligonucleotide chips

Oligonucleotide chips are microarrays of oligonucleotides.[3] They can be used for detection of mutations and expression monitoring, and gene discovery and mapping.[22] The main methods for creating an oligonucleotide microarray are by gel pads (Motorola), microelectrodes (Nanogen), photolithography (Affymetrix), and inkjet technology (Agilent).[22]

- Using gel pads, prefabricated oligonucleotides are attached to patches of activated polyacrylamide[22]

- Using microelectrodes, negatively charged DNA and molecular probes can be concentrated on energized electrodes for interaction[23]

- Using photolithography, a light exposure pattern is created on the substrate using a photomask or virtual photomask projected from a digital micromirror device.[3][6] The light removes photoliabile protecting groups from the selected exposure areas.[6] Following de-protection, nucleotides with a photolabile protecting group are exposed to the entire surface and the chemical coupling process only occurs where light was exposed in the previous step.[6] This process can be repeated to synthesize oligonucleotides of relatively short lengths on the surface, nucleotide by nucleotide.[6]

- Using inkjet technology, nucleotides are printed onto a surface drop by drop to form oligonucleotides[22]

cDNA microarray

cDNA microarrays are often used for large-scale screening and expression studies.[22] In cDNA microarrays, mRNA from cells are collected and converted into cDNA by reverse transcription.[3] Subsequently, cDNA molecules (each corresponding to one gene) are immobilized as ~100 µm diameter spots on a membrane, glass, or silicon chip by metallic pins.[3][22] For detection, fluorescently-labelled single strand cDNA from cells hybridize to the molecules on the microarray and a differential comparison between a treated sample (labelled red, for example) and an untreated sample (labelled in another color such as green) is used for analysis.[3] Red dots mean that the corresponding gene was expressed at a higher level in the treated sample. Conversely, green dots mean that the corresponding gene was expressed at a higher level in the untreated sample. Yellow dots, as a result of the overlap between red and green dots, mean that the corresponding gene was expressed at relatively the same level in both samples, whereas dark spots indicate no or negligible expression in either sample.

Peptide and protein microarrays

The motivation for using peptide and protein microarrays is firstly because mRNA transcripts often correlate poorly with the actual amount of protein synthesized.[24] Secondly, DNA microarrays cannot identify post-translational modification of proteins, which directly influences protein function.[24] Thirdly, some bodily fluids such as urine lack mRNA.[24] A protein microarray consists of a protein library immobilized on a substrate chip, usually glass, silicon, polystyrene, PVDF, or nitrocellulose.[24] In general, there are three types of protein microarrays: functional, analytical or capture, and reverse-phase protein arrays.[25]

- Functional protein arrays display folded and active proteins and are used for screening molecular interactions, studying protein pathways, identifying targets for post-translational modification, and analyzing enzymatic activities.[25]

- Analytical or capture protein arrays display antigens and antibodies to profile protein or antibody expression in serum.[25] These arrays can be used for biomarker discovery, monitoring of protein quantities, monitoring activity states in signalling pathways, and profiling antibody repertories in diseases.[25]

- Reverse-phase protein arrays test replicates of cell lysates and serum samples with different antibodies to study the changes in expression of specific proteins and protein modifications during disease progression, as well as biomarker discovery.[25]

Protein microarrays have stringent production, storage, and experimental conditions due to the low stability and necessity of considering the native folding on the immobilized proteins.[26] Peptides, on the other hand, are more chemically resistant and can retain partial aspects of protein function.[26] As such, peptide microarrays have been used to complement protein microarrays in proteomics research and diagnostics. Protein microarrays usually use Escherichia coli to produce proteins of interest; whereas peptide microarrays use the SPOT technique (stepwise synthesis of peptides on cellulose) or photolithography to make peptides.[25][26]

PCR chips

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a fundamental molecular biology technique that enables the selective amplification of DNA sequences, which is useful for expanded use of rare samples e.g.: stem cells, biopsies, circulating tumor cells.[3] The reaction involves thermal cycling of the DNA sequence and DNA polymerase through three different temperatures. Heating up and cooling down in conventional PCR devices are time-consuming and typical PCR reactions can take hours to complete.[28] Other drawbacks of conventional PCR is the high consumption of expensive reagents, preference for amplifying short fragments, and the production of short chimeric molecules.[28] PCR chips serves to miniaturize PCR into microfluidic bio-MEMS and can achieve rapid heat transfer and fast mixing due to the larger surface-to-volume ratio and short diffusion distances respectively.[28] The advantages of PCR chips include shorter thermal-cycling time, more uniform temperatures during the PCR process for enhanced yield, and portability for point-of-care applications.[28] Two challenges in microfluidic PCR chips are PCR inhibition and contamination due to the large surface-to-volume ratio increasing surface-reagent interactions.[28] For example, silicon substrates have good thermal conductivity for rapid heating and cooling, but can poison the polymerase reaction.[3] There are stationary (chamber-based), dynamic (continuous flow-based), and microdroplet (digital PCR) chip architectures.[3]

- Chamber-based architecture is the result of shrinking down of conventional PCR reactors, which is difficult to scale up.[3] A four-layer glass-PDMS device has been developed using this architecture integrating microvalves, microheaters, temperature sensors, 380-nL reaction chambers, and capillary electrophoresis channels for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) that has attomolar detection sensitivity.[29]

- Continuous flow-based architecture moves the sample through different temperature zones to achieve thermal cycling.[28] This approach uses less energy and has high throughput, but has large reagent consumption and gas bubbles can form inside the flow channels.[3]

- Digital PCR eliminates sample/reagent surface adsorption and contamination by carrying out PCR in microdroplets or microchambers.[28] PCR in droplets also prevents recombination of homologous gene fragments so synthesis of short chimeric products is eliminated.[28]

Point-of-care-diagnostic devices

.jpg)

The ability to perform medical diagnosis at the bedside or at the point-of-care is important in health care, especially in developing countries where access to centralized hospitals is limited and prohibitively expensive. To this end, point-of-care diagnostic bio-MEMS have been developed to take saliva, blood, or urine samples and in an integrated approach perform sample preconditioning, sample fractionation, signal amplification, analyte detection, data analysis, and result display.[3] In particular, blood is a very common biological sample because it cycles through the body every few minutes and its contents can indicate many aspects of health.[3]

Sample conditioning

In blood analysis, white blood cells, platelets, bacteria, and plasma must be separated.[3] Sieves, weirs, inertial confinement, and flow diversion devices are some approaches used in preparing blood plasma for cell-free analysis.[3] Sieves can be microfabricated with high-aspect-ratio columns or posts, but are only suitable for low loading to avoid clogging with cells.[3] Weirs are shallow mesa-like sections used to restrict flow to narrow slots between layers without posts.[3] One advantage of using weirs is that the absence of posts allows more effective recycling of retenate for flow across the filter to wash off clogged cells.[3] The H-filter is a microfluidic device with two inlets and two outlets that takes advantage of laminar flow and diffusion to separate components that diffuse across the interface between two inlet streams.[3] By controlling the flow rate, diffusion distance, and residence time of the fluid in the filter, cells are excluded from the filtrate by virtue of their slower diffusion rate.[3] The H-filter does not clog and can run indefinitely, but analytes are diluted by a factor of two.[3] For cell analysis, cells can be studied intact or after lysis.[3] A lytic buffer stream can be introduced alongside a stream containing cells and by diffusion induces lysis prior to further analysis.[3] Cell analysis is typically done by flow cytometry and can be implemented into microfluidics with lower fluid velocities and lower throughput than their conventional macroscopic counterparts.[3]

Sample fractionation

Microfluidic sample separation can be achieved by capillary electrophoresis or continuous-flow separation.[3] In capillary electrophoresis, a long thin tube separates analytes by voltage as they migrate by electro-osmotic flow.[3] For continuous-flow separation, the general idea is to apply a field at an angle to the flow direction to deflect the sample flow path toward different channels.[3] Examples of continuous-flow separation techniques include continuous-flow electrophoresis, isoelectric focusing, continuous-flow magnetic separations, and molecular sieving.[3]

Bio-MEMS in tissue engineering

Cell culture

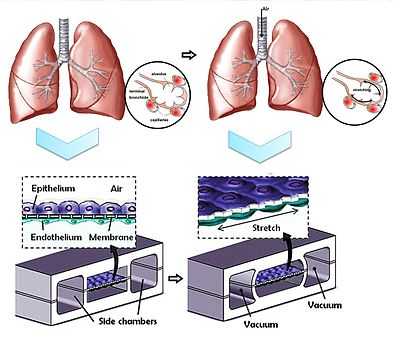

Conventional cell culture technology is unable to efficiently allow combinatorial testing of drug candidates, growth factors, neuropeptides, genes, and retroviruses in cell culture medium.[3] Due to the need for cells to be fed periodically with fresh medium and passaged, even testing a few conditions requires a large number of cells and supplies, expensive and bulky incubators, large fluid volumes (~0.1 – 2 mL per sample), and tedious human labour.[3] The requirement of human labour also limits the number and length between time points for experiments. Microfluidic cell cultures are potentially a vast improvement because they can be automated, as well as yield lower overall cost, higher throughput, and more quantitative descriptions of single-cell behaviour variability.[13] By including gas exchange and temperature control systems on chip, microfluidic cell culturing can eliminate the need for incubators and tissue culture hoods.[3] However, this type of continuous microfluidic cell culture operation presents its own unique challenges as well. Flow control is important when seeding cells into microchannels because flow needs to be stopped after the initial injection of cell suspension for cells to attach or become trapped in microwells, dielectrophoretic traps, micromagnetic traps, or hydrodynamic traps.[3] Subsequently, flow needs to be resumed in a way that does not produce large forces that shear the cells off the substrate.[3] Dispensing fluids by manual or robotic pipetting can be replaced with micropumps and microvalves, where fluid metering is straightforward to determine as opposed to continuous flow systems by micromixers.[3] A fully automated microfluidic cell culture system has been developed to study osteogenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells.[30] A handheld microfluidic cell culture incubator capable of heating and pumping cell culture solutions has also been developed.[31] Due to the volume reduction in microfluidic cultures, the collected concentrations are higher for better signal-to-noise ratio measurements, but collection and detection is correspondingly more difficult.[3] In situ microscopy assays with microfluidic cell cultures may help in this regard, but have inherently lower throughput due to the microscope probe having only a small field of view.[3] Micropatterned co-cultures have also contributed to bio-MEMS for tissue engineering to recapitulate in vivo conditions and 3D natural structure. Specifically, hepatocytes have been patterned to co-culture at specific cell densities with fibroblasts to maintain liver-specific functions such as albumin secretion, urea synthesis, and p450 detoxification.[32] Similarly, integrating microfluidics with micropatterned co-cultures has enabled modelling of organs where multiple vascularized tissues interface, such as the blood–brain barrier and the lungs.[3] Organ-level lung functions have been reconstituted on lung-on-a-chip devices where a porous membrane and the seeded epithelial cell layer are cyclically stretched by applied vacuum on adjacent microchannels to mimic inhalation.[33]

Stem-cell engineering

The goal of stem cell engineering is to be able to control the differentiation and self-renewal of pluripotency stem cells for cell therapy. Differentiation in stem cells is dependent on many factors, including soluble and biochemical factors, fluid shear stress, cell-ECM interactions, cell-cell interactions, as well as embryoid body formation and organization.[35] Bio-MEMS have been used to research how to optimize the culture and growth conditions of stem cells by controlling these factors.[3] Assaying stem cells and their differentiated progeny is done with microarrays for studying how transcription factors and miRNAs determine cell fate, how epigenetic modifications between stem cells and their daughter cells affect phenotypes, as well as measuring and sorting stem cells by their protein expression.[35]

Biochemical factors

Microfluidics can leverage its microscopic volume and laminar flow characteristics for spatiotemporal control of biochemical factors delivered to stem cells.[35] Microfluidic gradient generators have been used to study dose-response relationships.[36] Oxygen is an important biochemical factor to consider in differentiation via hypoxia-induced transcription factors (HIFs) and related signaling pathways, most notably in the development of blood, vasculature, placental, and bone tissues.[35] Conventional methods of studying oxygen effects relied on setting the entire incubator at a particular oxygen concentration, which limited analysis to pair-wise comparisons between normoxic and hypoxic conditions instead of the desired concentration-dependent characterization.[35] Developed solutions include the use of continuous axial oxygen gradients[37] and arrays of microfluidic cell culture chambers separated by thin PDMS membranes to gas-filled microchannels.[38]

Fluid shear stress

Fluid shear stress is relevant in the stem cell differentiation of cardiovascular lineages as well as late embryogenesis and organogenesis such as left-right asymmetry during development.[35] Macro-scale studies do not allow quantitative analysis of shear stress to differentiation because they are performed using parallel-plate flow chambers or rotating cone apparatuses in on-off scenarios only.[35] Poiseuille flow in microfluidics allows shear stresses to be varied systematically using channel geometry and flow rate via micropumps, as demonstrated by using arrays of perfusion chambers for mesenchymal stem cells and fibroblast cell adhesion studies.[35][39]

Cell–ECM interactions

Cell-ECM interactions induce changes in differentiation and self-renewal by the stiffness of the substrate via mechanotransduction, and different integrins interacting with ECM molecules.[35] Micropatterning of ECM proteins by micro-contact printing (μCP), inkjet printing, and mask spraying have been used in stem cell-ECM interaction studies.[35] It has been found by using micro-contact printing to control cell attachment area that that switch in osteogenic / adipogenic lineage in human mesenchymal stem cells can be cell shape dependent.[40] Microfabrication of microposts and measurement of their deflection can determine traction forces exerted on cells.[35] Photolithography can also be used to cross-link cell-seeded photo-polymerizable ECM for three-dimensional studies.[41] Using ECM microarrays to optimize combinatorial effects of collagen, laminin, and fibronectin on stem cells is more advantageous than conventional well plates due to its higher throughput and lower requirement of expensive reagents.[42]

Cell–cell interactions

Cell fate is regulated by both interactions between stem cells and interactions between stem cells and membrane proteins.[35] Manipulating cell seeding density is a common biological technique in controlling cell–cell interactions, but controlling local density is difficult and it is often difficult to decouple effects between soluble signals in the medium and physical cell–cell interactions.[35] Micropatterning of cell adhesion proteins can be used in defining the spatial positions of different cells on a substrate to study human ESC proliferation.[35] Seeding stem cells into PDMS microwells and flipping them onto a substrate or another cell layer is a method of achieving precise spatial control.[43] Gap junction communications has also been studied using microfluidics whereby negative pressure generated by fluid flow in side channels flanking a central channel traps pairs of cells that are in direct contact or separated by a small gap.[44] However, in general, the non-zero motility and short cell cycle time of stem cells often disrupt the spatial organization imposed by these microtechnologies.[35]

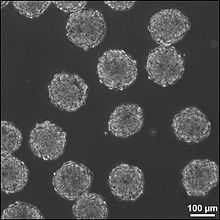

Embryoid body formation and organization

Embryoid bodies are a common in vitro pluripotency test for stem cells and their size needs to be controlled to induce directed differentiation to specific lineages.[35] High throughput formation of uniform sized embryoid bodies with microwells and microfluidics allows easy retrieval and more importantly, scale up for clinical contexts.[35][45] Actively controlling embryoid body cell organization and architecture can also direct stem cell differentiation using microfluidic gradients of endoderm-, mesoderm- and ectoderm-inducing factors, as well as self-renewal factors.[46]

Assisted reproductive technologies

Assisted reproductive technologies help to treat infertility and genetically improve livestock.[3] However, the efficiency of these technologies in cryopreservation and the in vitro production of mammalian embryos is low.[3] Microfluidics have been applied in these technologies to better mimic the in vivo microenvironment with patterned topographic and biochemical surfaces for controlled spatiotemporal cell adhesion, as well as minimization of dead volumes.[3] Micropumps and microvalves can automate tedious fluid-dispensing procedures and various sensors can be integrated for real-time quality control. Bio-MEMS devices have been developed to evaluate sperm motility,[47] perform sperm selection,[48] as well as prevent polyspermy[49] in in-vitro fertilization.

Bio-MEMS in medical implants and surgery

Implantable microelectrodes

The goal of implantable microelectrodes is to interface with the body’s nervous system for recording and sending bioelectrical signals to study disease, improve prostheses, and monitor clinical parameters.[3] Microfabrication has led to the development of Michigan probes and the Utah electrode array, which have increased electrodes per unit volume, while addressing problems of thick substrates causing damage during implantation and triggering foreign-body reaction and electrode encapsulation via silicon and metals in the electrodes.[3] Michigan probes have been used in large-scale recordings and network analysis of neuronal assemblies ,[50] and the Utah electrode array has been used as a brain–computer interface for the paralyzed.[51] Extracellular microelectrodes have been patterned onto an inflatable helix-shaped plastic in cochlear implants to improve deeper insertion and better electrode-tissue contact for transduction of high-fidelity sounds.[52] Integrating microelectronics onto thin, flexible substrates has led to the development of a cardiac patch that adheres to the curvilinear surface of the heart by surface tension alone for measuring cardiac electrophysiology,[53] and electronic tattoos for measuring skin temperature and bioelectricity.[54]

Microtools for surgery

Bio-MEMS for surgical applications can improve existing functionality, add new capabilities for surgeons to develop new techniques and procedures, and improve surgical outcomes by lowering risk and providing real-time feedback during the operation.[55] Micromachined surgical tools such as tiny forceps, microneedle arrays and tissue debriders have been made possible by metal and ceramic layer-by-layer microfabrication techniques for minimally invasive surgery and robotic surgery.[3][55] Incorporation of sensors onto surgical tools also allows tactile feedback for the surgeon, identification of tissue type via strain and density during cutting operations, and diagnostic catheterization to measure blood flows, pressures, temperatures, oxygen content, and chemical concentrations.[3][55]

Drug delivery

Microneedles, formulation systems, and implantable systems are bio-MEMS applicable to drug delivery.[56] Microneedles of approximately 100μm can penetrate the skin barrier and deliver drugs to the underlying cells and interstitial fluid with reduced tissue damage, reduced pain, and no bleeding.[3][56] Microneedles can also be integrated with microfluidics for automated drug loading or multiplexing.[3] From the user standpoint, microneedles can be incorporated into a patch format for self-administration, and do not constitute a sharp waste biohazard (if the material is polymeric).[3] Drug delivery by microneedles include coating the surface with therapeutic agents, loading drugs into porous or hollow microneedles, or fabricating the microneedles with drug and coating matrix for maximum drug loading.[56] Microneedles for interstitial fluid extraction, blood extraction, and gene delivery are also being developed.[3][56] The efficiency of microneedle drug delivery remains a challenge because it is difficult to ascertain if the microneedles effectively penetrated the skin. Some drugs, such as diazepam, are poorly soluble and need to be aerosolized immediately prior to intranasal administration.[56] Bio-MEMS technology using piezoelectric transducers to liquid reservoirs can be used in these circumstances to generate narrow size distribution of aerosols for better drug delivery.[56] Implantable drug delivery systems have also been developed to administer therapeutic agents that have poor bioavailability or require localized release and exposure at a target site.[56] Examples include a PDMS microfluidic device implanted under the conjunctiva for drug delivery to the eye to treat ocular diseases[57] and microchips with gold-capped drug reservoirs for osteoporosis.[56] In implantable bio-MEMS for drug delivery, it is important to consider device rupture and dose dumping, fibrous encapsulation of the device, and device explantation.[56][58] Most drugs also need to be delivered in relatively large quantities (milliliters or even greater), which makes implantable bio-MEMS drug delivery challenging due to their limited drug-holding capacity.

References

- ↑ Sieben, Vincent J.; Debes-Marun, Carina S.; Pilarski, Linda M.; Backhouse, Christopher J. (2008). "An integrated microfluidic chip for chromosome enumeration using fluorescence in situ hybridization". Lab on a Chip 8 (12): 2151–6. doi:10.1039/b812443d. ISSN 1473-0197. PMID 19023479.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Steven S. Saliterman (2006). Fundamentals of bio-MEMS and medical microdevices. Bellingham, Wash., USA: SPIE—The International Society for Optical Engineering. ISBN 0-8194-5977-1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 3.29 3.30 3.31 3.32 3.33 3.34 3.35 3.36 3.37 3.38 3.39 3.40 3.41 3.42 3.43 3.44 3.45 3.46 3.47 3.48 3.49 3.50 3.51 3.52 3.53 3.54 3.55 3.56 3.57 3.58 3.59 3.60 3.61 3.62 3.63 3.64 3.65 3.66 3.67 3.68 3.69 3.70 3.71 3.72 3.73 3.74 3.75 3.76 3.77 3.78 3.79 3.80 Folch, Albert (2013). Introduction to bio-MEMS. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-1839-8.

- ↑ Manz, A.; Graber, N.; Widmer, H.M. (1990). "Miniaturized total chemical analysis systems: A novel concept for chemical sensing". Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 1 (1–6): 244–248. doi:10.1016/0925-4005(90)80209-I. ISSN 0925-4005.

- ↑ Whitesides, George M. (2006). "The origins and the future of microfluidics". Nature 442 (7101): 368–373. doi:10.1038/nature05058. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16871203.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Fodor, S.; Read, J.; Pirrung, M.; Stryer, L; Lu, A.; Solas, D (1991). "Light-directed, spatially addressable parallel chemical synthesis". Science 251 (4995): 767–773. doi:10.1126/science.1990438. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 1990438.

- ↑ Henry, Sebastien; McAllister, Devin V.; Allen, Mark G.; Prausnitz, Mark R. (1998). "Microfabricated microneedles: A novel approach to transdermal drug delivery". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 87 (8): 922–925. doi:10.1021/js980042+. ISSN 0022-3549.

- ↑ Kopp, M. U.; de Mello, A. J.; Manz, A. (1998). "Chemical Amplification: Continuous-Flow PCR on a Chip". Science 280 (5366): 1046–1048. doi:10.1126/science.280.5366.1046. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 9582111.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Takayama, S.; McDonald, J. C.; Ostuni, E.; Liang, M. N.; Kenis, P. J. A.; Ismagilov, R. F.; Whitesides, G. M. (1999). "Patterning cells and their environments using multiple laminar fluid flows in capillary networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (10): 5545–5548. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.10.5545. ISSN 0027-8424.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 Nguyen, Nam -Trung (2006). "5 Fabrication Issues of Biomedical Micro Devices". BioMEMS and Biomedical Nanotechnology: 93–115. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-25845-4_5.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 11.18 11.19 11.20 11.21 11.22 11.23 Bashir, Rashid (2004). "Bio-MEMS: state-of-the-art in detection, opportunities and prospects". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 56 (11): 1565–1586. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2004.03.002. ISSN 0169-409X. PMID 15350289.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Barbosa, Mário A.; Mandal, Kalpana; Balland, Martial; Bureau, Lionel (2012). "Thermoresponsive Micropatterned Substrates for Single Cell Studies". PLoS ONE 7 (5): e37548. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037548. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3365108. PMID 22701519.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Venkat Chokkalingam, Jurjen Tel, Florian Wimmers, Xin Liu, Sergey Semenov, Julian Thiele, Carl G. Figdor, Wilhelm T.S. Huck, Probing cellular heterogeneity in cytokine-secreting immune cells using droplet-based microfluidics, Lab on a Chip, 13, 4740-4744, 2013, DOI: 10.1039/C3LC50945A, http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/lc/c3lc50945a#!divAbstract

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bhatia, Sangeeta N.; Chen, Christopher S. (1999). Biomedical Microdevices 2 (2): 131–144. doi:10.1023/A:1009949704750. ISSN 1387-2176. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Voldman, Joel (2003). "Bio-MEMS: Building with cells". Nature Materials 2 (7): 433–434. doi:10.1038/nmat936. ISSN 1476-1122. PMID 12876566.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Lu, Yao; Shi, Weiwei; Qin, Jianhua; Lin, Bingcheng (2010). "Fabrication and Characterization of Paper-Based Microfluidics Prepared in Nitrocellulose Membrane By Wax Printing". Analytical Chemistry 82 (1): 329–335. doi:10.1021/ac9020193. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 20000582.

- ↑ Rubinsky, Boris; Aki, Atsushi; Nair, Baiju G.; Morimoto, Hisao; Kumar, D. Sakthi; Maekawa, Toru (2010). "Label-Free Determination of the Number of Biomolecules Attached to Cells by Measurement of the Cell's Electrophoretic Mobility in a Microchannel". PLoS ONE 5 (12): e15641. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015641. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3012060. PMID 21206908.

- ↑ Ulijn, Rein; Courson, David S.; Rock, Ronald S. (2009). "Fast Benchtop Fabrication of Laminar Flow Chambers for Advanced Microscopy Techniques". PLoS ONE 4 (8): e6479. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006479. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2714461. PMID 19649241.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Vo-Dinh, Tuan (2006). "Biosensors and Biochips". BioMEMS and Biomedical Nanotechnology: 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-25845-4_1.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Wu, Z; Choudhury, Khujesta; Griffiths, Helen; Xu, Jinwu; Ma, Xianghong (2012). "A novel silicon membrane-based biosensing platform using distributive sensing strategy and artificial neural networks for feature analysis". Biomed Microdevices 14 (1): 83–93. doi:10.1007/s10544-011-9587-6. ISSN 1572-8781. PMID 21915644.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Homola, Jiří (2008). "Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors for Detection of Chemical and Biological Species". Chemical Reviews 108 (2): 462–493. doi:10.1021/cr068107d. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 18229953.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 Gabig M, Wegrzyn G (2001). "An introduction to DNA chips: principles, technology, applications and analysis". Acta Biochim. Pol. 48 (3): 615–22. PMID 11833770.

- ↑ Huang, Ying; Hodko, Dalibor; Smolko, Daniel; Lidgard, Graham (2006). "Electronic Microarray Technology and Applications in Genomics and Proteomics". BioMEMS and Biomedical Nanotechnology: 3–21. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-25843-0_1.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Talapatra, Anupam; Rouse, Richard; Hardiman, Gary (2002). "Protein microarrays: challenges and promises". Pharmacogenomics 3 (4): 527–536. doi:10.1517/14622416.3.4.527. ISSN 1462-2416. PMID 12164775.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Stoevesandt, Oda; Taussig, Michael J; He, Mingyue (2009). "Protein microarrays: high-throughput tools for proteomics". Expert Review of Proteomics 6 (2): 145–157. doi:10.1586/epr.09.2. ISSN 1478-9450. PMID 19385942.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Tapia, Victor E.; Ay, Bernhard; Volkmer, Rudolf (2009). "Exploring and Profiling Protein Function with Peptide Arrays". Methods in Molecular Biology 570: 3–17. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-394-7_1. ISSN 1064-3745.

- ↑ Wanunu, Meni; Cao, Qingqing; Mahalanabis, Madhumita; Chang, Jessie; Carey, Brendan; Hsieh, Christopher; Stanley, Ahjegannie; Odell, Christine A.; Mitchell, Patricia; Feldman, James; Pollock, Nira R.; Klapperich, Catherine M. (2012). "Microfluidic Chip for Molecular Amplification of Influenza A RNA in Human Respiratory Specimens". PLoS ONE 7 (3): e33176. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033176. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3310856. PMID 22457740.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 28.7 Zhang, Yonghao; Ozdemir, Pinar (2009). "Microfluidic DNA amplification—A review". Analytica Chimica Acta 638 (2): 115–125. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2009.02.038. ISSN 0003-2670. PMID 19327449.

- ↑ Toriello, Nicholas M.; Liu, Chung N.; Mathies, Richard A. (2006). "Multichannel Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction Microdevice for Rapid Gene Expression and Biomarker Analysis". Analytical Chemistry 78 (23): 7997–8003. doi:10.1021/ac061058k. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 17134132.

- ↑ Gómez-Sjöberg, Rafael; Leyrat, Anne A.; Pirone, Dana M.; Chen, Christopher S.; Quake, Stephen R. (2007). "Versatile, Fully Automated, Microfluidic Cell Culture System". Analytical Chemistry 79 (22): 8557–8563. doi:10.1021/ac071311w. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 17953452.

- ↑ Futai, Nobuyuki; Gu, Wei; Song, Jonathan W.; Takayama, Shuichi (2006). "Handheld recirculation system and customized media for microfluidic cell culture". Lab on a Chip 6 (1): 149–54. doi:10.1039/b510901a. ISSN 1473-0197. PMID 16372083.

- ↑ Bhatia, S.N.; Balis, U.J.; Yarmush, M.L.; Toner, M. (1998). "Probing heterotypic cell interactions: Hepatocyte function in microfabricated co-cultures". Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition 9 (11): 1137–1160. doi:10.1163/156856298X00695. ISSN 0920-5063.

- ↑ Huh, D.; Matthews, B. D.; Mammoto, A.; Montoya-Zavala, M.; Hsin, H. Y.; Ingber, D. E. (2010). "Reconstituting Organ-Level Lung Functions on a Chip". Science 328 (5986): 1662–1668. doi:10.1126/science.1188302. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 20576885.

- ↑ Yang, Yanmin; Tian, Xiliang; Wang, Shouyu; Zhang, Zhen; Lv, Decheng (2012). "Rat Bone Marrow-Derived Schwann-Like Cells Differentiated by the Optimal Inducers Combination on Microfluidic Chip and Their Functional Performance". PLoS ONE 7 (8): e42804. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042804. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3411850. PMID 22880114.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 35.6 35.7 35.8 35.9 35.10 35.11 35.12 35.13 35.14 35.15 35.16 Toh, Yi-Chin; Blagović, Katarina; Voldman, Joel (2010). "Advancing stem cell research with microtechnologies: opportunities and challenges". Integrative Biology 2 (7–8): 305–25. doi:10.1039/c0ib00004c. ISSN 1757-9694. PMID 20593104.

- ↑ Chung, Bong Geun; Flanagan, Lisa A.; Rhee, Seog Woo; Schwartz, Philip H.; Lee, Abraham P.; Monuki, Edwin S.; Jeon, Noo Li (2005). "Human neural stem cell growth and differentiation in a gradient-generating microfluidic device". Lab on a Chip 5 (4): 401–6. doi:10.1039/b417651k. ISSN 1473-0197. PMID 15791337.

- ↑ Allen, J. W. (2005). "In Vitro Zonation and Toxicity in a Hepatocyte Bioreactor". Toxicological Sciences 84 (1): 110–119. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfi052. ISSN 1096-0929. PMID 15590888.

- ↑ Lam, Raymond H. W.; Kim, Min-Cheol; Thorsen, Todd (2009). "Culturing Aerobic and Anaerobic Bacteria and Mammalian Cells with a Microfluidic Differential Oxygenator". Analytical Chemistry 81 (14): 5918–5924. doi:10.1021/ac9006864. ISSN 0003-2700. PMC 2710860. PMID 19601655.

- ↑ Lu, Hang; Koo, Lily Y.; Wang, Wechung M.; Lauffenburger, Douglas A.; Griffith, Linda G.; Jensen, Klavs F. (2004). "Microfluidic Shear Devices for Quantitative Analysis of Cell Adhesion". Analytical Chemistry 76 (18): 5257–5264. doi:10.1021/ac049837t. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 15362881.

- ↑ McBeath, Rowena; Pirone, Dana M; Nelson, Celeste M; Bhadriraju, Kiran; Chen, Christopher S (2004). "Cell Shape, Cytoskeletal Tension, and RhoA Regulate Stem Cell Lineage Commitment". Developmental Cell 6 (4): 483–495. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00075-9. ISSN 1534-5807. PMID 15068789.

- ↑ Albrecht, Dirk R.; Tsang, Valerie Liu; Sah, Robert L.; Bhatia, Sangeeta N. (2005). "Photo- and electropatterning of hydrogel-encapsulated living cell arrays". Lab on a Chip 5 (1): 111–8. doi:10.1039/b406953f. ISSN 1473-0197. PMID 15616749.

- ↑ Flaim, Christopher J; Chien, Shu; Bhatia, Sangeeta N (2005). "An extracellular matrix microarray for probing cellular differentiation". Nature Methods 2 (2): 119–125. doi:10.1038/nmeth736. ISSN 1548-7091. PMID 15782209.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Adam; Macdonald, Alice; Voldman, Joel (2007). "Cell patterning chip for controlling the stem cell microenvironment". Biomaterials 28 (21): 3208–3216. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.023. ISSN 0142-9612. PMC 1929166. PMID 17434582.

- ↑ Lee, Philip J.; Hung, Paul J.; Shaw, Robin; Jan, Lily; Lee, Luke P. (2005). "Microfluidic application-specific integrated device for monitoring direct cell-cell communication via gap junctions between individual cell pairs". Applied Physics Letters 86 (22): 223902. doi:10.1063/1.1938253. ISSN 0003-6951.

- ↑ Torisawa, Yu-suke; Chueh, Bor-han; Huh, Dongeun; Ramamurthy, Poornapriya; Roth, Therese M.; Barald, Kate F.; Takayama, Shuichi (2007). "Efficient formation of uniform-sized embryoid bodies using a compartmentalized microchannel device". Lab on a Chip 7 (6): 770–6. doi:10.1039/b618439a. ISSN 1473-0197. PMID 17538720.

- ↑ Fung, Wai-To; Beyzavi, Ali; Abgrall, Patrick; Nguyen, Nam-Trung; Li, Hoi-Yeung (2009). "Microfluidic platform for controlling the differentiation of embryoid bodies". Lab on a Chip 9 (17): 2591–5. doi:10.1039/b903753e. ISSN 1473-0197. PMID 19680583.

- ↑ Kricka LJ, Nozaki O, Heyner S, Garside WT, Wilding P (September 1993). "Applications of a microfabricated device for evaluating sperm function". Clin. Chem. 39 (9): 1944–7. PMID 8375079.

- ↑ Cho, Brenda S.; Schuster, Timothy G.; Zhu, Xiaoyue; Chang, David; Smith, Gary D.; Takayama, Shuichi (2003). "Passively Driven Integrated Microfluidic System for Separation of Motile Sperm". Analytical Chemistry 75 (7): 1671–1675. doi:10.1021/ac020579e. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 12705601.

- ↑ Clark, Sherrie G.; Haubert, Kathyrn; Beebe, David J.; Ferguson, C. Edward; Wheeler, Matthew B. (2005). "Reduction of polyspermic penetration using biomimetic microfluidic technology during in vitro fertilization". Lab on a Chip 5 (11): 1229–32. doi:10.1039/b504397m. ISSN 1473-0197. PMID 16234945.

- ↑ Buzsáki, György (2004). "Large-scale recording of neuronal ensembles". Nature Neuroscience 7 (5): 446–451. doi:10.1038/nn1233. ISSN 1097-6256. PMID 15114356.

- ↑ Hochberg, Leigh R.; Serruya, Mijail D.; Friehs, Gerhard M.; Mukand, Jon A.; Saleh, Maryam; Caplan, Abraham H.; Branner, Almut; Chen, David; Penn, Richard D.; Donoghue, John P. (2006). "Neuronal ensemble control of prosthetic devices by a human with tetraplegia". Nature 442 (7099): 164–171. doi:10.1038/nature04970. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16838014.

- ↑ Arcand, B. Y.; Bhatti, P. T.; Butala, N. V.; Wang, J.; Friedrich, C. R.; Wise, K. D. (2004). "Active positioning device for a perimodiolar cochlear electrode array". Microsystem Technologies 10 (6–7): 478–483. doi:10.1007/s00542-004-0376-5. ISSN 0946-7076.

- ↑ Viventi, J.; Kim, D.-H.; Moss, J. D.; Kim, Y.-S.; Blanco, J. A.; Annetta, N.; Hicks, A.; Xiao, J.; Huang, Y.; Callans, D. J.; Rogers, J. A.; Litt, B. (2010). "A Conformal, Bio-Interfaced Class of Silicon Electronics for Mapping Cardiac Electrophysiology". Science Translational Medicine 2 (24): 24ra22–24ra22. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3000738. ISSN 1946-6234.

- ↑ Kim, D.-H.; Lu, N.; Ma, R.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, R.-H.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Won, S. M.; Tao, H.; Islam, A.; Yu, K. J.; Kim, T.-i.; Chowdhury, R.; Ying, M.; Xu, L.; Li, M.; Chung, H.-J.; Keum, H.; McCormick, M.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Omenetto, F. G.; Huang, Y.; Coleman, T.; Rogers, J. A. (2011). "Epidermal Electronics". Science 333 (6044): 838–843. doi:10.1126/science.1206157. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 21836009.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Rebello, K.J. (2004). "Applications of MEMS in Surgery". Proceedings of the IEEE 92 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2003.820536. ISSN 0018-9219.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 56.6 56.7 56.8 Nuxoll, E.; Siegel, R. (2009). "Bio-MEMS devices for drug delivery". IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine 28 (1): 31–39. doi:10.1109/MEMB.2008.931014. ISSN 0739-5175. PMID 19150769.

- ↑ Lo, Ronalee; Li, Po-Ying; Saati, Saloomeh; Agrawal, Rajat; Humayun, Mark S.; Meng, Ellis (2008). "A refillable microfabricated drug delivery device for treatment of ocular diseases". Lab on a Chip 8 (7): 1027–30. doi:10.1039/b804690e. ISSN 1473-0197. PMID 18584074.

- ↑ Shawgo, Rebecca S; Richards Grayson, Amy C; Li, Yawen; Cima, Michael J (2002). "Bio-MEMS for drug delivery". Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science 6 (4): 329–334. doi:10.1016/S1359-0286(02)00032-3. ISSN 1359-0286.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||