Bicoid (gene)

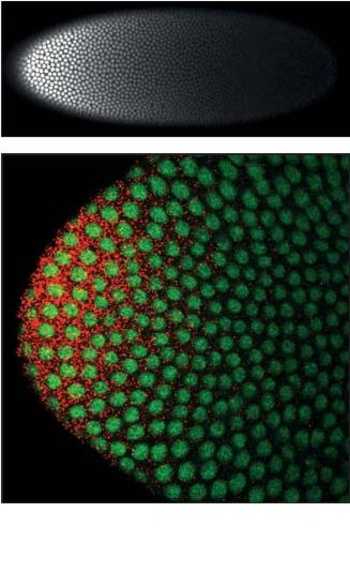

Bicoid is a maternal effect gene whose protein concentration gradient patterns the anterior-posterior axis during Drosophila embryogenesis. Bicoid was also the first protein demonstrated to act as a morphogen.[2]

Role of Bicoid in axial patterning

bicoid mRNA is actively localized to the anterior of the fruit fly egg during oogenesis[3] along microtubules[4][5] and retained there through association with cortical actin.<ref name="Weil2006>Weil, T. T.; Forrest, K. M.; Gavis, E. R. (2006). "Localization of bicoid mRNA in Late Oocytes is Maintained by Continual Active Transport". Developmental Cell 11 (2): 251. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.006.</ref> Translation of bicoid is regulated by its 3' UTR and begins after egg deposition: diffusion and convection within the syncytium produce an exponential gradient of Bicoid protein[2][6] within roughly one hour, after which Bicoid nuclear concentrations remain approximately constant through cellularization.[7] Bicoid protein represses the translation of caudal mRNA and enhanced the transcription of anterior gap genes including hunchback, orthodenticle, and buttonhead.

Structure and function of Bicoid

Bicoid is one of few proteins which binds both RNA and DNA targets using its homeodomain to regulate their transcription and translation, respectively. The nucleic acid-binding homeodomain of Bicoid has been solved by NMR.[8] Bicoid contains an arginine-rich motif (part of the helix shown axially in this image) that is similar to the one found in the HIV protein REV is essential for its nucleic acid binding.[9]

Bicoid gradient scaling

Bicoid protein gradient formation is one of the earliest steps in fruit fly embryo A-P patterning: the proper spatial expression of downstream genes relies on the robustness of this gradient to common variations between embryos, including in the number of maternally-deposited bicoid mRNAs and in egg size. Comparative phylogenetic[10] and experimental evolution[11] studies suggest an inherent mechanism for robust generation of a scaled Bicoid protein gradient. Mechanisms that have been proposed to effect this scaling include non-linear degradation of Bicoid,[12] nuclear retention as a size-dependent regulator of Bicoid protein's effective diffusion coefficient,[6][13] and scaling of cytoplasmic streaming.[6]

References

- ↑ Little, S. C.; Tkačik, G. P.; Kneeland, T. B.; Wieschaus, E. F.; Gregor, T. (2011). "The Formation of the Bicoid Morphogen Gradient Requires Protein Movement from Anteriorly Localized mRNA". PLoS Biology 9 (3): e1000596. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000596.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Driever, W.; Nüsslein-Volhard, C. (1988). "The bicoid protein determines position in the Drosophila embryo in a concentration-dependent manner". Cell 54: 95. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90183-3.

- ↑ St. Johnston D, Driever W, Berleth T, Richstein S, Nusslein-Volhard C (1989). Multiple steps in the localization of bicoid RNA to the anterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Development 107 Suppl: 13–19.

- ↑ Pokrywka, N. J.; Stephenson, E. C. (1991). "Microtubules mediate the localization of bicoid RNA during Drosophila oogenesis". Development (Cambridge, England) 113 (1): 55–66. PMID 1684934.

- ↑ Weil, T. T.; Parton, R.; Davis, I.; Gavis, E. R. (2008). "Changes in bicoid mRNA Anchoring Highlight Conserved Mechanisms during the Oocyte-to-Embryo Transition". Current Biology 18 (14): 1055. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.046.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Hecht, I.; Rappel, W. -J.; Levine, H. (2009). "Determining the scale of the Bicoid morphogen gradient". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (6): 1710. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807655106.

- ↑ Gregor, T.; Wieschaus, E. F.; McGregor, A. P.; Bialek, W.; Tank, D. W. (2007). "Stability and Nuclear Dynamics of the Bicoid Morphogen Gradient". Cell 130: 141. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.026.

- ↑ Baird-Titus, J. M.; Clark-Baldwin, K.; Dave, V.; Caperelli, C. A.; Ma, J.; Rance, M. (2006). "The Solution Structure of the Native K50 Bicoid Homeodomain Bound to the Consensus TAATCC DNA-binding Site". Journal of Molecular Biology 356 (5): 1137. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.007.

- ↑ Niessing, D.; Driever, W.; Sprenger, F.; Taubert, H.; Jäckle, H.; Rivera-Pomar, R. (2000). "Homeodomain Position 54 Specifies Transcriptional versus Translational Control by Bicoid". Molecular Cell 5 (2): 395. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80434-7.

- ↑ Gregor, T.; McGregor, A. P.; Wieschaus, E. F. (2008). "Shape and function of the Bicoid morphogen gradient in dipteran species with different sized embryos". Developmental Biology 316 (2): 350. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.039.

- ↑ Cheung, D.; Miles, C.; Kreitman, M.; Ma, J. (2013). "Adaptation of the length scale and amplitude of the Bicoid gradient profile to achieve robust patterning in abnormally large Drosophila melanogaster embryos". Development 141 (1): 124–35. doi:10.1242/dev.098640. PMC 3865754. PMID 24284208.

- ↑ Eldar, A.; Rosin, D.; Shilo, B. Z.; Barkai, N. (2003). "Self-Enhanced Ligand Degradation Underlies Robustness of Morphogen Gradients". Developmental Cell 5 (4): 635. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00292-2.

- ↑ Grimm, O.; Wieschaus, E. (2010). "The Bicoid gradient is shaped independently of nuclei". Development 137 (17): 2857. doi:10.1242/dev.052589.