Bible translations into Polish

The earliest Bible translations into the Polish language date to the 13th century. The first full ones were completed in the 16th.

Presently in Poland the official and most popular Bible is the Millennium Bible (Biblia Tysiąclecia), first published in 1965 for the millennium of the 966 C.E. Baptism of Poland, which approximates the beginnings of Poland's statehood.

First translations

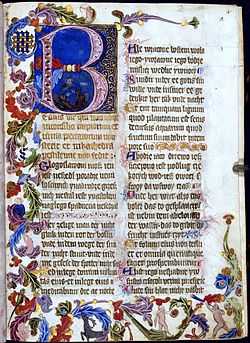

The history of Polish-language translation of the Bible begins with the Psalter. The earliest recorded translations date to the 13th century, around 1280; however, none of these survive.[1][2][3] The oldest surviving Polish translation of the Bible is the St. Florian's Psalter (Psałterz floriański), assumed to be a copy of that translation, itself a manuscript of the second half of the 14th century, in the abbey of Saint Florian, near Linz, in Latin, Polish and German.[1][2][4][5]

A critical edition of the Polish part of the St. Florian's Psalter was published by Wladysław Nehring[6] (Psalterii Florianensis pars Polonica, Poznań, 1883) with a very instructive introduction.

Slightly newer than the St. Florian's Psalter is the Puławy Psalter (now in Kraków) dating from the end of the 15th century (published in facsimile, Poznań, 1880).[2][5]

There were also a 16th-century translation of the New Testament, and more fragmentary translations, none of which have been preserved in their full form to the present.[2]

Polish Bibles originated in the mid-15th century. An incomplete Bible, the "Queen Sophia's Bible" (Biblia królowej Zofii, named after Sophia of Halshany, for whom it was intended, dating to before 1455), contains Genesis, Joshua, Ruth, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, II (III) Esdras, Tobit, and Judith.[5][7]

With the Reformation, translation activity increased as the different confessions endeavored to supply their adherents with texts of the Bible. An effort to secure a Polish-language Bible for Lutherans was made by Duke Albert of Prussia in a letter directed in his name to Melanchthon.

Brest Bible (1563)

Jan Seklucjan (1510–1578), preacher at Königsberg, was commissioned to prepare a translation, and he published the New Testament at Königsberg in 1551 and 1552.[2] The Polish Reformed (Calvinists) received the Bible through Prince Nicholas Radziwill (1515–65).[2] A company of Polish and foreign theologians and scholars undertook the task, and, after six years' labor at the "Sarmatian Athens" at Pińczów, not far from Kraków, finished the translation of the Bible which was published at the expense of Radziwill in Brest-Litovsk, 1563 (hence called the Brest Bible Biblia Brzeska).[2][8] The translators state that for the Old Testament they consulted besides the Hebrew text the ancient versions and different modern Latin ones.

Socinian versions

Two years after the Brest Bible was completed the Calvinist and Radical wings of the Reformed church split in 1565, and the Bible was suspect to both groups: The Calvinist Ecclesia Major suspected it of Arian interpretations; the Radical Ecclesia Minor complained that it was not accurate enough. Symon Budny, a Belarusian of the Judaizing wing of the Ecclesia Minor especially charged against the Brest Bible that it was not prepared according to the original texts, but after the Vulgate and other modern versions, and that the translators cared more for elegant Polish than for a faithful rendering. He undertook a new rendering, and his translation ("made anew from the Hebrew, Greek, and Latin into the Polish") was printed in 1572 at Nesvizh. As changes were introduced in the printing which were not approved by Budny, he disclaimed the New Testament and published another edition (1574) Zasłaŭje, and then finally a third edition (1589) where he withdrew some of his Judaizing and Talmudic readings. The charges which he made against the Brest Bible were also made against his own, and Budny's former colleague Marcin Czechowic of Lublin - who was concerned with Budny's preference for Hebrew over Greek sources - published the Polish Brethren's own edition of the New Testament (Cracow, 1577). The interesting preface states that Czechowic endeavored to make an accurate translation, but did not suppress his Socinian ideas; e.g., he used "immersion" instead of "baptism." A further truly Socinian Racovian New Testament was published by Valentinus Smalcius, a pupil of Fausto Sozzini (Racovian Academy, 1606).[9]

Danzig Bible (1632)

The Brest Bible was superseded by the so-called Danzig Bible (or Gdańsk Bible), which finally became the Bible of all Evangelical Poles.[2] At the synod in Ożarowice, 1600, a new edition of the Bible was proposed and the work was given to the Reformed minister Martin Janicki, who had already translated the Bible from the original texts.[2] In 1603 the printing of this translation was decided upon, after the work had been carefully revised. The work of revision was entrusted to men of the Reformed and Lutheran confessions and members of the Moravian Church (1604), especially to Daniel Mikołajewski (died 1633), superintendent of the Reformed churches in Great Poland, and Jan Turnowski, senior of the Moravian Church in Great Poland (died 1629).[2]

After it had been compared with the Janicki translation, the Brest, the Bohemian, Pagnini's Latin, and the Vulgate, the new rendering was ordered printed.[2] The Janicki translation as such has not been printed, and it is difficult to state how much of it is contained in the new Bible.[2] The New Testament was first published at Danzig, 1606, and very often during the 16th and 17th centuries. The complete Bible was issued in 1632, and often since.[2] The Danzig Bible differs so much from that of Brest that it may be regarded as a new translation. It is erroneously called also the Bible of Pavel Paliurus (1569–1632) (a Moravian, senior of the Evangelical Churches in Great Poland, d. 1632); but he had no part in the work.

Jakub Wujek's Bible (1599)

For the Roman Catholics the Bible was translated from the Vulgate by Jan Nicz of Lwów (Jan Leopolita, hence the Biblia Leopolity) Kraków, 1561, 1574, and 1577. This Bible was superseded by the new translation of the Jesuit Jakub Wujek (c.1540 - Kraków 1593) that became known as the Jakub Wujek Bible.[10][11] Wujek criticized the Leopolita and non-Catholic Bible versions and spoke very favorably of the Polish of the Brest Bible, but asserted that it was full of heresies and of errors in translation.[10][11] The first copies of Wujek's New Testament appeared in 1593 - containing Wujek's "teachings and warnings" regarding the Protestant versions.[10][11] Czechowic went into print with a booklet accusing Wujek of plagiarism and following the Latin over the Greek.[12] With the approbation of the Holy See the New Testament was first published at Kraków, 1593, and the Old Testament in 1599, after Wujek's death.[10][11] This Bible (Biblia Wujka) has often been reprinted.[10][11] Wujek's translation follows, in the main, the Vulgate.[10][11]

Modern versions

Today the official and most popular Bible in Poland is the Millennium Bible (Biblia Tysiąclecia) first published in 1965.[5][13] Other popular Catholic translations include the Poznań Bible (Biblia Poznańska, 1975) and Biblia Warszawsko-Praska (1997).[5]

Polish Protestants had been widely using Danzig Bible (Biblia Gdańska), until they prepared their modern translation: Warsaw Bible (Biblia Warszawska) in 1975.[5][13]

Jehovah's Witnesses have translated their New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures into Polish, as Przekład Nowego Świata (1984).[14][15]

In 2009 a grammatical update of the Danzig Bible New Testament, Uwspółcześniona Biblia Gdańska (UBG), containing cross references was published by the Foundation Wrota Nadziei in Toruń. The translation and modernization of archaisms found in the old Danzig Bible was done by a team of born again Polish and American Christians.[16]

Text examples

| John 3,16 | |

|---|---|

| Wujek Bible | Albowiem tak Bóg umiłował świat, że Syna swego jednorodzonego dał, aby wszelki, kto wierzy weń, nie zginał, ale miał życie wieczne. |

| Millennium Bible | Tak bowiem Bóg umiłował świat, że Syna swego Jednorodzonego dał, aby każdy, kto w Niego wierzy, nie zginął, ale miał życie wieczne. |

| Warsaw Bible | Albowiem tak Bóg umiłował świat, że Syna swego jednorodzonego dał, aby każdy, kto weń wierzy, nie zginął, ale miał żywot wieczny. |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Witold Taszycki (1975). Najdawniejsze zabytki języka polskiego. Zakł. Narod. im. Ossolińskich. p. 61. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 (Polish) ks. prof. dr Jan Szeruda Geneza i charakter Biblii Gdańskiej

- ↑ (Polish) Polskie tłumaczenia Biblii

- ↑ James Hastings (11 October 2004). A Dictionary Of The Bible: Supplement -- Articles. The Minerva Group, Inc. p. 418. ISBN 978-1-4102-1730-1. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Bernard Wodecki, Polish Translations of Bible, in Jože Krašovec (1998). Interpretation der Bibel. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 1232. ISBN 978-1-85075-969-0. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ↑ DNB

- ↑ Glanville Price (28 April 2000). Encyclopedia of the languages of Europe. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-631-22039-8. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ↑ David A. Frick (1989). Polish sacred philology in the Reformation and the counter-Reformation: chapters in the history of the controversies (1551-1632). University of California Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-520-09740-7. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ↑ University of California publications in modern philology, Volume 123 University of California, Berkeley

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 (Polish) Grzegorz Kubski, Wzór biblijnej polszczyzny (Model of Biblical Polish Language), Przewodnik Katolicki, 1 August 2007.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 (Polish) Stanisław Koziara, Biblia Wujka w języku i kulturze polskiej (Wujek's Bible in Polish Language and Culture)

- ↑ David A. Frick Polish sacred philology in the Reformation 1989 "Czechowic' s main criticism of Wujek 's New Testament of 1593 is that "Father Wujek took almost everything from my edition and placed it in his,"

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hans Dieter Betz; Don S. Browning; Bernd Janowski (2007). RPP religion past & present. Brill. p. 54. ISBN 978-90-04-14608-2. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ↑ University of Warsaw. Polish Language Institute—"Pismo Święte w Przekładzie Nowego Świata. Translated from the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures, ed. Of 1984." 2000.

- ↑ "Przekład Nowego Świata". Watch Tower Society.

- ↑ Fundacja Wrota Nadziei