Bhalil

| Bhalil al-Bahālīl / (Arabic) البهاليل | |

|---|---|

| town | |

Bhalil | |

| Coordinates: 33°51′N 4°52′W / 33.850°N 4.867°W | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Fès-Boulemane |

| Province | Sefrou Province |

| Elevation | 982 m (3,222 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 11,638 |

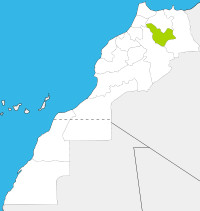

Bhalil (Arabic: البهاليل / al-Bahālīl) is a town in the north of Morocco.

Set on the side of a hill 6KM northwest of Sefrou, the village of Bhalil is notable for its unique cave houses located in the old part of the village, and for its eclectically coloured homes, linked together by a network of bridges.

Some of the cave houses in Bhalil are routinely open to tourists to visit, but are rapidly disappearing as the village modernizes. A tour of these houses can be arranged with friendly local guides at a nominal fee.

Bhalil is also known for its production of Jelleba Buttons. Village women can often be found in alleyways, chatting while they diligently work through hundreds of strings and buttons in the creation of traditional Jelleba.

The village is also known for its olive oil production, and traditional bread ovens.[1]

Coordinates: 33°51′N 4°52′E / 33.850°N 4.867°E

A Historic Account of Marriage Ceremonies in Bhalil (As Documented by Houcein Kaci) [2]

A mixture of rural and urban practices can be found in traditional marriage ceremonies of Bhalil, with evidence of Berber customs that seem to have disappeared elsewhere, but which are still evident in Bhalil's culture (as of 1921).

Houcein Kaci provides the Berber custom where after a few months of marriage, a bride will leave her husband and return to her ancestral family home for an entire year. Typically, people from Bhalil marry within the village because the two families will be well known to each other. Contrary to traditional customs, the young man approaches the young woman’s parents (and specifically the father) to ask for his daughter in marriage. In some situations, if the daughter is of a certain age, she is consulted and ultimately allowed to make the decision (however, her father can overrule her if he believes she is making an unwise decision).

For the entire engagement, the female fiancée does not leave the house, and likewise for three days prior to the wedding day, the male fiancé remains in an isolated cave with a few select male companions. Henna decorations occur on the second night before the wedding (for both the male and the female – her feet and hands are fully covered, and his hands only are decorated).

The male fiancé parades through the city on a highly embellished horse to his future home, where his bride is waiting. Celebrations occur for seven days afterward to celebrate the wedding. The bride cannot leave her bed for seven days after the wedding day, throughout which she is not allowed to see anyone but close family; and the groom continues living in the caves. On the seventh day, a final celebration occurs ot mark the end of the wedding and the beginning of their daily life as a married couple.

After five months, the wife must leave her husband for a year and return to live in her ancestral home. The husband and wife must not see each other for the entire year; throughout this period, the wife is cloistered, but accompanied by an older woman sent by the bride’s husband. After the year, the husband gives his in-laws a variety of gifts (generally livestock and eggs) and the husband and wife return to their daily lives. The real name of Bahalil is Bahau El-Lail which is the Night's Glory or Night's éclat.

The Traditional Pottery Techniques and Design Patterns of Bhalil

An article written by J. Herber in 1946 [3] (who visited the area in 1928, with the intent of studying Moroccan pottery techniques and decoration in rural areas) explores the various techniques used by male and female potters from Bhalil.

Herber's examination of two male potters found that both used traditional techniques that were specific to Bhalil and the surrounding area due to the type of earth and clay that could be found in the area near the village. The tools and cooking techniques were likewise area specific, and tools were often made by the potter himself, resulting in fairly straightforward and simple designs.

Decorations on the pottery were made with either a very fine tip (in straight lines or diamonds) or pieces of reed/the thumb nail to make crescent shapes (these designs are seen to be reminiscent of Saharan sculptors). The pottery made in this area was designed to be functional, as it would be used on a daily basis. Much of the originality of Bhalil potters lie in the designing of their tools and the brazier (mejmar), which varied in design and decoration depending on the potter. Female potters in Bhalil have very different styles of crafting from those of the males. Herber was not able to observe the females in their practice, as he visited in April, and females only traveled in the autumn months to avoid the heat of the summer, but he made note of this custom.

Female potters in Bhalil also used local earth, but it was slightly different from those of the males (it was found right in Bhalil itself). The techniques were very similar to other female potters from the Zerhoun region as the earth was modeled on a stand and cooked in the sun; however, the main differences lay in the design of the pottery. Much of the pottery was again made for common, everyday use but it was decorated either externally or internally with black lines and zigzags. Although the pottery done by females in Bhalil was still fairly rustic, it was more often finished more finely than that of the males. Overall, Herber found that the design and techniques used in Bhalil, and Morocco more generally, varied across different areas and tribes. However, there are heavy Berber influences that can be found in the decor of ceramics in North Africa, which are reflected in other artisan styles as well (tattoos, fabric and rug designs of the region).

| |||||||||||||||||