Beta (plasma physics)

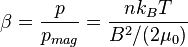

The beta of a plasma, symbolized by β, is the ratio of the plasma pressure (p = n kB T) to the magnetic pressure (pmag = B²/2μ0). The term is commonly used in studies of the Sun and Earth's magnetic field, and in the field of fusion power designs.

In the fusion power field, plasma is often confined using large superconducting magnets that are very expensive. Since the temperature of the fuel scales with pressure, reactors attempt to reach the highest pressures possible. The costs of large magnets roughly scales like β½. Therefore beta can be thought of as a ratio of money out to money in for a reactor, and beta can be thought of (very approximately) as an economic indicator of reactor efficiency. To make an economically useful reactor, betas better than 5% are needed.

The same term is also used when discussing the interactions of the solar wind with various magnetic fields. For example, the beta in the corona of the Sun is about 1%.

Background

Fusion basics

Nuclear fusion occurs when the nuclei of two atoms approach closely enough for the nuclear force to pull them together into a single larger nucleus. The strong force is opposed by the electrostatic force created by the positive charge of the nuclei's protons, pushing the nuclei apart. The amount of energy that is needed to overcome this repulsion is known as the Coulomb barrier. The amount of energy released by the fusion reaction when it occurs may be greater or less than the Coulomb barrier. Generally, lighter nuclei with a smaller number of protons and greater number of neutrons will have the greatest ratio of energy released to energy required, and the majority of fusion power research focusses on the use of deuterium and tritium, two isotopes of hydrogen.

Even using these isotopes, the Coulomb barrier is large enough that the nuclei must be given great amounts of energy before they will fuse. Although there are a number of ways to do this, the simplest is to simply heat the gas mixture, which, according to the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution, will result in a small number of particles with the required energy even when the gas as a whole is relatively "cool" compared to the Coulomb barrier energy. In the case of the D-T mixture, rapid fusion will occur when the gas is heated to about 100 million degrees.[1]

Confinement

This temperature is well beyond the physical limits of any material container that might contain the gasses, which has led to a number of different approaches to solving this problem. The main approach relies on the nature of the fuel at high temperatures. When the fusion fuel gasses are heated to the temperatures required for rapid fusion, they will be completely ionized into a plasma, a mixture of electrons and nuclei forming a globally neutral gas. As the particles within the gas are charged, this allows them to be manipulated by electric or magnetic fields. This gives rise to the majority of controlled fusion concepts.

Even if this temperature is reached, the gas will be constantly losing energy to its surroundings (cooling off). This gives rise to the concept of the "confinement time", the amount of time the plasma is maintained at the required temperature. However, the fusion reactions might deposit their energy back into the plasma, heating it back up, which is a function of the density of the plasma. These considerations are combined in the Lawson criterion, or its modern form, the fusion triple product. In order to be efficient, the rate of fusion energy being deposited into the reactor would ideally be greater than the rate of loss to the surroundings, a condition known as "ignition".

Magnetic confinement fusion approach

In magnetic confinement fusion (MCF) reactor designs, the plasma is confined within a vacuum chamber using a series of magnetic fields. These fields are normally created using a combination of electromagnets and electrical currents running through the plasma itself. Systems using only magnets are generally built using the stellarator approach, while those using current only are the pinch machines. The most studied approach since the 1970s is the tokamak, where the fields generated by the external magnets and internal current are roughly equal in magnitude.

In all of these machines, the density of the particles in the plasma is very low, often described as a "poor vacuum". This limits its approach to the triple product along the temperature and time axis. This requires magnetic fields on the order of tens of Teslas, currents in the megaampere, and confinement times on the order of tens of seconds.[2] Generating currents of this magnitude is relatively simple, and a number of devices from large banks of capacitors to homopolar generators have been used. However, generating the required magnetic fields is another issue, generally requiring expensive superconducting magnets. For any given reactor design, the cost is generally dominated by the cost of the magnets.

Beta

Given that the magnets are a dominant factor in reactor design, and that density and temperature combine to produce pressure, the ratio of the pressure of the plasma to the magnetic energy density naturally becomes a useful figure of merit when comparing MCF designs. In effect, the ratio illustrates how effectively a design confines its plasma. This ratio, beta, is widely used in the fusion field:

is normally measured in terms of the total magnetic field. However, in any real-world design, the strength of the field varies over the volume of the plasma, so to be specific, the average beta is sometimes referred to as the "beta toroidal". In the tokamak design the total field is a combination of the external toroidal field and the current-induced poloidal one, so the "beta poloidal" is sometimes used to compare the relative strengths of these fields. And as the external magnetic field is the driver of reactor cost, "beta external" is used to consider just this contribution.

is normally measured in terms of the total magnetic field. However, in any real-world design, the strength of the field varies over the volume of the plasma, so to be specific, the average beta is sometimes referred to as the "beta toroidal". In the tokamak design the total field is a combination of the external toroidal field and the current-induced poloidal one, so the "beta poloidal" is sometimes used to compare the relative strengths of these fields. And as the external magnetic field is the driver of reactor cost, "beta external" is used to consider just this contribution.

Troyon beta limit

For a stable plasma,  is always smaller than 1 (otherwise it would collapse).[4] Ideally, a MCF device would want to approach this limit as closely as possible, as this would imply the minimum amount of magnetic force needed for confinement. In practice, it is difficult to come even close to this, and production machines generally operate at betas around 0.1, or 10%. The record was set by the START device at 0.4, or 40%.[5]

is always smaller than 1 (otherwise it would collapse).[4] Ideally, a MCF device would want to approach this limit as closely as possible, as this would imply the minimum amount of magnetic force needed for confinement. In practice, it is difficult to come even close to this, and production machines generally operate at betas around 0.1, or 10%. The record was set by the START device at 0.4, or 40%.[5]

These low achievable betas are due to instabilities in the plasma generated through the interaction of the fields and the motion of the particles due to the induced current. As the amount of current is increased in relation to the external field, these instabilities become uncontrollable. In early pinch experiments the current dominated the field components and the kink and sausage instabilities were common, today collectively referred to as "low-n instabilities". As the relative strength of the external magnetic field is increased, these simple instabilities are damped out, but at a critical field other "high-n instabilities" will invariably appear, notably the ballooning mode. For any given reactor design, there is a limit to the beta it can sustain. As beta is a measure of economic merit, a practical reactor must be able to sustain a beta above some critical value, which is calculated to be around 5%.[6]

Through the 1980s the understanding of the high-n instabilities grew considerably. Shafranov and Yurchenko first published on the issue in 1971 in a general discussion of tokamak design, but it was the work by Wesson and Sykes in 1983[7] and Francis Troyon in 1984[8] that developed these concepts fully. Troyon's considerations, or the "Troyon limit", closely matched the real-world performance of existing machines. It has since become so widely used that it is often known simply as the beta limit.

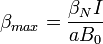

The Troyon limit is given as:

Where I is the plasma current,  is the external magnetic field, and a is the minor radius of the tokamak (see torus for an explanation of the directions).

is the external magnetic field, and a is the minor radius of the tokamak (see torus for an explanation of the directions).  was determined numerically, and is normally given as 0.028 if I is measured in megaamperes. However, it is also common to use 2.8 if

was determined numerically, and is normally given as 0.028 if I is measured in megaamperes. However, it is also common to use 2.8 if  is expressed as a percentage.[9]

is expressed as a percentage.[9]

Given that the Troyon limit suggested a  around 2.5 to 4%, and a practical reactor had to have a

around 2.5 to 4%, and a practical reactor had to have a  around 5%, the Troyon limit was a serious concern when it was introduced. However, it was found that

around 5%, the Troyon limit was a serious concern when it was introduced. However, it was found that  changed dramatically with the shape of the plasma, and non-circular systems would have much better performance. Experiments on the DIII-D machine (the second D referring to the cross-sectional shape of the plasma) demonstrated higher performance,[10] and the spherical tokamak design outperformed the Troyon limit by about 10 times.[11]

changed dramatically with the shape of the plasma, and non-circular systems would have much better performance. Experiments on the DIII-D machine (the second D referring to the cross-sectional shape of the plasma) demonstrated higher performance,[10] and the spherical tokamak design outperformed the Troyon limit by about 10 times.[11]

Astrophysics

Beta is also sometimes used when discussing the interaction of plasma in space with different magnetic fields. A common example is the interaction of the solar wind with the magnetic fields of the Sun[12] or Earth.[13] In this case, the betas of these natural phenomena are generally much smaller than those seen in reactor designs; the Sun's corona has a beta around 1%.[12] Active regions have much higher beta, over 1 in some cases, which makes the area unstable.[14]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Bromberg, pg. 18

- ↑ "Conditions for a fusion reaction", JET

- ↑ Wesson, J: "Tokamaks", 3rd edition page 115, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ↑ Kenrō Miyamoto, "Plasma Physics and Controlled Nuclear Fusion", Springer, 2005 , pg. 62

- ↑ Alan Sykes, "The Development of the Spherical Tokamak", ICPP, Fukuoka September 2008

- ↑ "Scientific Progress in Magnetic Fusion, ITER, and the Fusion Development Path", SLAC Colloquium, 21 April 2003, pg. 17

- ↑ Alan Sykes et all, Proceedings of 11th European Conference on Controlled Fusion and Plasma Physics, 1983, pg. 363

- ↑ F. Troyon et all, Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion, Volume 26, pg. 209

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Friedberg, pg. 397

- ↑ T. Taylor, "Experimental Achievement of Toroidal Beta Beyond That Predicted by 'Troyon' Scaling", General Atomics, September 1994

- ↑ Sykes, pg. 29

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Alan Hood, "The Plasma Beta", Magnetohydrostatic Equilibria, 11 January 2000

- ↑ G. Haerendel et all, "High-beta plasma blobs in the morningside plasma sheet", Annales Geophysicae, Volume 17 Number 12, pg. 1592-1601

- ↑ G. Allan Gary, "Plasma Beta Above a Solar Active region: Rethinking the Paradigm", Solar Physics, Volume 203 (2001), pg. 71–86

Bibliography

- Joan Lisa Bromberg, "Fusion: Science, Politics, and the Invention of a New Energy Source", MIT Press, 1982

- Jeffrey Freidberg, "Plasma Physics and Fusion Energy", Cambridge University Press, 2007