Bernoulli's inequality

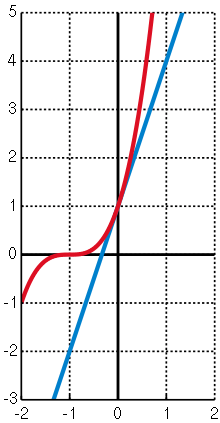

and

and  shown in red and blue respectively. Here,

shown in red and blue respectively. Here,

In real analysis, Bernoulli's inequality (named after Jacob Bernoulli) is an inequality that approximates exponentiations of 1 + x.

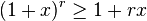

The inequality states that

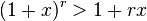

for every integer r ≥ 0 and every real number x ≥ −1. If the exponent r is even, then the inequality is valid for all real numbers x. The strict version of the inequality reads

for every integer r ≥ 2 and every real number x ≥ −1 with x ≠ 0.

Bernoulli's inequality is often used as the crucial step in the proof of other inequalities. It can itself be proved using mathematical induction, as shown below.

History

Jacob Bernoulli first published the inequality in his treatise “Positiones Arithmeticae de Seriebus Infinitis” (Basel, 1689), were he used the inequality often.[1]

According to Joseph E. Hofmann, Über die Exercitatio Geometrica des M. A. Ricci (1963), p. 177, the inequality is actually due to Sluse in his Mesolabum (1668 edition), Chapter IV "De maximis & minimis".[1]

Proof of the inequality

For r = 0,

is equivalent to 1 ≥ 1 which is true as required.

Now suppose the statement is true for r = k:

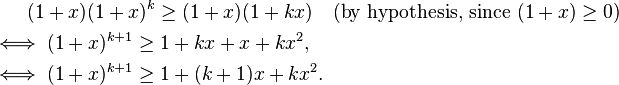

Then it follows that

However, as 1 + (k + 1)x + kx2 ≥ 1 + (k + 1)x (since kx2 ≥ 0), it follows that (1 + x)k + 1 ≥ 1 + (k + 1)x, which means the statement is true for r = k + 1 as required.

By induction we conclude the statement is true for all r ≥ 0.

Generalization

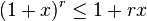

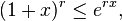

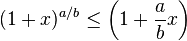

The exponent r can be generalized to an arbitrary real number as follows: if x > −1, then

for r ≤ 0 or r ≥ 1, and

for 0 ≤ r ≤ 1.

This generalization can be proved by comparing derivatives. Again, the strict versions of these inequalities require x ≠ 0 and r ≠ 0, 1.

Related inequalities

The following inequality estimates the r-th power of 1 + x from the other side. For any real numbers x, r > 0, one has

where e = 2.718.... This may be proved using the inequality (1 + 1/k)k < e.

Alternative form

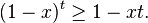

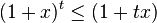

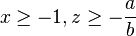

An alternative form of Bernoulli's inequality for  and

and  is:

is:

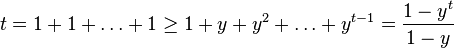

This can be proved (for integer t) by using the formula for geometric series: (using y=1-x)

or equivalently

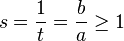

Proof for rational case

An "elementary" proof can be given using the fact that geometric mean of positive numbers is less than arithmetic mean

First assume

By comparing Arithmetic and Geometric mean of  numbers

(

numbers

( occurs

occurs  times):

times):

we get

or equivalently

This proves inequality for  case.

case.

For  case,

let

case,

let  As

As  we get with

we get with  ,

,

This proves inequality for  case.

case.

As these inequalities are true for all rational numbers  and

and  ,

they are also true for all real numbers, which follows from a density argument of the rationals in the reals, and the fact that the functions involved are continuous.

,

they are also true for all real numbers, which follows from a density argument of the rationals in the reals, and the fact that the functions involved are continuous.

Notes

References

- Carothers, N.L. (2000). Real analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-521-49756-5.

- Bullen, P. S. (2003). Handbook of means and their inequalities. Dordercht [u.a.]: Kluwer Academic Publ. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4020-1522-9.

- Zaidman, S. (1997). Advanced calculus : an introduction to mathematical analysis. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific. p. 32. ISBN 978-981-02-2704-3.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Bernoulli Inequality", MathWorld.

- Bernoulli Inequality by Chris Boucher, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Arthur Lohwater (1982). "Introduction to Inequalities". Online e-book in PDF format.

- Paper “Some Equivalent Forms of Bernoulli’s Inequality: A Survey“