Bernie Grant

| Bernie Grant | |

|---|---|

| |

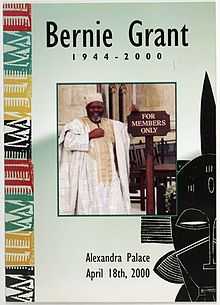

| Grant's funeral programme | |

| Member of Parliament for Tottenham | |

| In office 11 June 1987 – 8 April 2000 | |

| Preceded by | Norman Atkinson |

| Succeeded by | David Lammy |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 February 1944 Georgetown, Guyana |

| Died | 8 April 2000 (aged 56) |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Labour |

| Profession | politician |

| Religion | Christian |

Bernard Alexander Montgomery Grant (17 February 1944 – 8 April 2000), known simply as Bernie Grant, was a British Labour Party politician who was the Member of Parliament for Tottenham from 1987 to his death in 2000.

Biography

Bernie Grant was born in Georgetown, Guyana, to schoolteacher parents, who in 1963 took up the British government's offer to people from the colonies to settle in the UK. Grant attended Tottenham technical college, and went on to take a degree course in mining engineering at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh.[1]

In the mid-1960s he was for a period a member of the Socialist Labour League. He quickly became a trade union official, and moved into politics, becoming a Labour councillor in the London Borough of Haringey in 1978.

When the Conservative government introduced "rate capping", Grant led the fight against it in the borough . This split the local Labour Party, but through this split Grant became the Borough of Haringey leader in 1985.

He took control of the rebuilding project of Alexandra Palace, which had been partially destroyed in a fire. The project had £15 million in cash, but the lack of financial control saw this surplus turn into deficit and interest payments eventually took the debt to a total of £80 million.

As Council leader during the 1985 Broadwater Farm riot, in which a policeman, PC Blakelock, was murdered, Grant was brought to national attention when he was widely quoted as saying: "What the police got was a bloody good hiding." Grant claimed his words had been taken out of context, but offered an apology to the family of PC Blakelock. A fuller version of the quotation is: "The youths around here believe the police were to blame for what happened on Sunday and what they got was a bloody good hiding."[2] His comments brought swift denunciation from the Labour Party leadership and the then Conservative Home Secretary, Douglas Hurd, called him "the high priest of conflict" and several British newspapers dubbed him "Barmy Bernie". He claimed that he was merely explaining to a wider audience what the feeling on the estate was like. There is conflicting information whether Grant condemned the violence of the rioters the following day.[3][4][5]

The controversy, however, did not prevent him becoming MP for Tottenham in the 1987 election, one of only three black MPs at the time, the others being Diane Abbott and Paul Boateng. Grant later stood for the deputy leadership of the Labour Party.

In 1989, he established and chaired the Parliamentary Black Caucus, modelled after the Congressional Black Caucus of the United States. The organization was committed to advancing the opportunities of Britain's ethnic minority communities.[6]

Grant was associated with the Socialist Campaign Group, and spoke out against police racism. He was married three times, living with his last wife in Muswell Hill. He died from a heart attack on 8 April 2000, aged 56. His funeral procession on 18 April passed through Tottenham towards a service at Alexandra Palace, pausing as it passed the Broadwater Farm estate. According to The Guardian′s report, "An estimated 3,000 people... turned out to salute the black radical. There were dancers and singers, a Highland piper and African drums. Also present were home secretary, Jack Straw, Chris Smith, culture secretary, Clare Short, minister for international development, and Paul Boateng and Keith Vaz, Britain's most senior black ministers."[7]

Legacy

His widow, Sharon Grant, was on the shortlist to succeed him as Labour candidate for Tottenham, but was beaten by the then-27-year-old David Lammy, who won the by-election in June 2000.[8]

In September 2007 in Tottenham, London, Haringey Council opened the Bernie Grant Arts Centre in his name.[9]

On Sunday, 28 October 2012, a blue plaque, organised by the Nubian Jak Community Trust, was unveiled at Tottenham Old Town Hall in tribute to Bernie Grant.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Mike Phillips, "Bernie Grant -Passionate leftwing MP and tireless anti-racism campaigner" (obituary), The Guardian, 10 April 2000.

- ↑ Dean Woodward, "Changing man: Bernie Grant February 17 1944 - April 8 2000", Weekly Worker, 13 April 2000.

- ↑ Ryle, Sarah (9 April 2000). "Farewell to a firebrand". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ↑ "BBC:Bernie Grant: A controversial figure". BBC. 2000-04-08. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ↑ "Bernie Grant Archive". Bernie Grant Trust.

- ↑ Rule, Sheila (3 April 1989). "British M.P.'s Form Caucus to Advance Rights of Minorities". The New York Times.

- ↑ Michael White, "Tottenham turns out in style for Bernie Grant's funeral", The Guardian, Wednesday, 19 April 2000.

- ↑ David Lammy, "A Tribute to Bernie Grant", Tuesday, 10 October 2000.

- ↑ "About Bernie", Bernie Grants Arts Centre website.

- ↑ Bruce Thain, "Hundreds turn out for Bernie Grant plaque unveiling", Haringey Independent, 29 October 2012.

External links

- Mike Phillips, "Bernie Grant -Passionate leftwing MP and tireless anti-racism campaigner" (obituary), The Guardian, 10 April 2000.

- Black Presence - Bernie Grant MP

- berniegrantarchive.org.uk The Bernie Grant Archives, held at Bishopsgate Institute

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Norman Atkinson |

Member of Parliament for Tottenham 1987–2000 |

Succeeded by David Lammy |

|