Bent metallocene

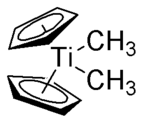

In organometallic chemistry, bent metallocenes are a subset of metallocenes. In bent metallocenes, the ring systems coordinated to the metal are not parallel, but are tilted at an angle. A common example of a bent metallocene is Cp2TiCl2.[1][2] Several reagents and much research is based on bent metallocenes.

Synthesis

Like regular metallocenes, bent metallocenes are synthesized by a variety of methods but most typically by reaction of sodium cyclopentadienide with the metal halide. This method applies to the synthesis of the bent metallocene dihalides of titanium, zirconium, hafnium, and vanadium:

- 2 NaC5H5 + TiCl4 → (C5H5)2TiCl2 + 2 NaCl

In the earliest work in this area, Grignard reagents were used to deprotonate the cyclopentadiene.[3]

Niobocene dichloride, featuring Nb(IV), is prepared via a multistep reaction that begins with a Nb(V) precursor:[4]

- NbCl5 + 6 NaC5H5 → 5 NaCl + (C5H5)4Nb + organic products

- (C5H5)4Nb + 2 HCl + 0.5 O2) → [{C5H5)2NbCl}2O]Cl2 + 2 C5H6

- 2 HCl + [{(C5H5)2NbCl}2O]Cl2 + SnCl2 → 2 (C5H5)2NbCl2 + SnCl4 + H2O

Bent metallocene dichlorides of molybdenum and tungsten are also prepared via indirect routes that involve redox at the metal centres.

- Bent metalloceneds

Structure and bonding

Bent metallocenes have ideallized C2v symmetry. The non-Cp ligands are arrayed in the wedge area. For bent metallocenes with the formula Cp2ML2, the L-M-L angle depends on the electron count. In the d2-complex molybdocene dichloride (Cp2MoCl2) the Cl-Mo-Cl angle is 82°. In the d1 complex niobocene dichloride, this angle is more open at 85.6°. In the d0-complex zirconocene dichloride the angle is even more open at 92.1°. This trend reveals that the frontier orbital, which is dz2, is oriented in the MCl2 plane but does not bisect the MCl2 angle.[5]

Reactivity

Salt metathesis reactions

Since bent metallocenes typically have other ligands, often halides, these additional sites are centers of reactivity. For example reduction of zirconacene dichloride gives the corresponding hydrido chloride called Schwartz's reagent:[6]

- (C5H5)2ZrCl2 + 1/4 LiAlH4 → (C5H5)2ZrHCl + 1/4 "LiAlCl4"

This hydride reagent is useful for organic synthesis. Related titanium-based complexes Petasis reagent and Tebbe's reagent also feature bent metallocenes. Titanocene pentasulfide is used in research on polysulfur rings. Alkyne and benzyne derivatives of titanocene are reagents in organic synthesis.[7][8]

Reactions of Cp rings

Although the Cp ligands are generally safely considered spectator ligands, they are not completely inert. For example, attempts to prepare titanocene by reduction of titanocene dichloride affords complexes of fulvalene ligands.

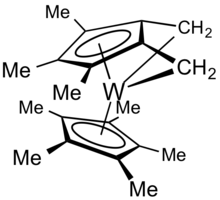

Bent metallocenes derived from pentamethylcyclopentadiene can undergo reactions involving the methyl groups. For example, decamethyltungstocene dihydride undergoes dehydrogenation to give the tuck-in complex.[2]

The original example proceeded via sequential loss of two equivalents of H2 from decamethyltungstocene dihydride, Cp*2WH2. The first dehydrogenation step affords a simple tuck-in complex:

- (C5Me5)2WH2 → (C5Me5)(C5Me3(CH2)2)W + 2 H2

Redox

When the non-Cp ligands are halides, these complexes undergo reduction to give carbonyl, alkene, and alkyne complexes that are useful reagents. A well known example is titanocene dicarbonyl:

- Cp2TiCl2 + Mg + 2 CO → Cp2Ti(CO)2 + MgCl2

Reduction of vanadocene dichloride gives vanadocene.

Olefin polymerization catalysis

Although bent metallocenes are of no commercial value as olefin polymerization catalysts, studies on these compounds were highly influential on the industrial processes. Already in 1957 there were reports on the polymerization of ethylene using a catalyst prepared from Cp2TiCl2 and trimethyl aluminium. Reactions involving the related Cp2Zr2Cl2/Al(CH3)3 system revealed the beneficial effects of trace amounts of water for ethylene polymerization. It is now known that the partially hydrolyzed organoaluminium reagent methylaluminoxane ("MAO") gives rise to families of highly active catalysts.[2] Work in this are led to constrained geometry complexes, which are not bent metallocenes, but exhibit related structural features.

References

- ↑ Jennifer Green (1998). "Bent Metallocenes Revisited". Chemical Society Reviews 27: 263–271. doi:10.1039/a827263z.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Roland Frohlich et al. (2006). "Group 4 Bent Metallocences and Functional Groups". Coordination Chemistry Reviews 250: 36–46.

- ↑ G. Wilkinson and M. Birmingham (1954). "Bis-Cyclopentadienyl Compounds of Ti, Zr, V, Nb and Ta". Journal of the American Chemical Society 76: 4281–4284. doi:10.1021/ja01646a008.

- ↑ C. R. Lucas (1990). "Dichlorobis(η5-Cyclopentadienyl)Niobium(IV)". Inorg. Synth. 28: 267–270. doi:10.1002/9780470132593.ch68. ISBN 0-471-52619-3.

- ↑ K. Prout, T. S. Cameron, R. A. Forder, and in parts S. R. Critchley, B. Denton and G. V. Rees "The crystal and molecular structures of bent bis-π-cyclopentadienyl-metal complexes: (a) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldibromorhenium(V) tetrafluoroborate, (b) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldichloromolybdenum(IV), (c) bis-π-cyclopentadienylhydroxomethylaminomolybdenum(IV) hexafluorophosphate, (d) bis-π-cyclopentadienylethylchloromolybdenum(IV), (e) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldichloroniobium(IV), (f) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldichloromolybdenum(V) tetrafluoroborate, (g) μ-oxo-bis[bis-π-cyclopentadienylchloroniobium(IV)] tetrafluoroborate, (h) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldichlorozirconium" Acta Cryst. 1974, volume B30, pp. 2290-2304. doi:10.1107/S0567740874007011

- ↑ S.M. King et al. (2005). "Schwartz’s Reagent". Organic Synthesis 9: 162.

- ↑ S.L. Buchwald and R.B. Nielsen (1988). "Group 4 Metal Complexes of Benzynes, Cycloalkynes, Acyclic Alkynes, and Alkenes". Chemical Reviews 88 (7): 1047–1058. doi:10.1021/cr00089a004.

- ↑ U. Rosenthal et al. (2000). "What Do Titano- and Zirconocenes Do with Diynes and Polyynes?". Chemical Reviews 33 (2): 119–129. doi:10.1021/ar9900109.

Further reading

- Stephen G. Davies et al. (1977). "Nucleophilic Addition to Organotransition Metal Cations Containing Unsaturated Hydrocarbon Ligands". Tetrahedron 34: 3047–3077. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(78)87001-X.,

- Robert C. Fay et al. (1982). "Five-Coordinate Bent Metallocenes". Inorganic Chemistry 22: 759–770. doi:10.1021/ic00147a011..

- Helmut Werner (2009). "Landmarks in Organotransition Metal Chemistry". Profiles in Inorganic Chemistry 1: 129–175. doi:10.1007/b136581.

2.png)