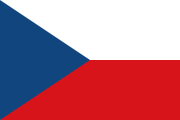

Beneš decrees

| Beneš decrees | |

|---|---|

Edvard Beneš, 1935–1938 and 1940–1948 President of Czechoslovakia | |

| Decrees of the President of the Republic | |

| Enacted by | National Assembly of the Czechoslovak Republic |

| Introduced by | Czechoslovak government-in-exile |

The Decrees of the President of the Republic (Czech: Dekrety presidenta republiky, Slovak: Dekréty prezidenta republiky) and the Constitutional Decrees of the President of the Republic (Czech: Ústavní dekrety presidenta republiky, Slovak: Ústavné dekréty prezidenta republiky), commonly known as the Beneš decrees, were a series of laws drafted by the Czechoslovak government-in-exile in the absence of the Czechoslovak parliament during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in World War II. They were issued by President Edvard Beneš from 21 July 1940 to 27 October 1945, and retroactively ratified by the Interim National Assembly of Czechoslovakia on 6 March 1946.

In journalism and political history, "Beneš decrees" refer to the decrees of the president and the ordinances of the Slovak National Council dealing with the status of ethnic Germans, Hungarians and others in postwar Czechoslovakia. These decrees facilitated the enforcement of Article 12 of the Potsdam Agreement by laying a national legal framework for the loss of citizenship and expropriation of the property of about three million Germans and Hungarians. Some of those affected held land settled by their ancestors since their invitation by the Czech king Otokar II during the 13th century or the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin at the turn of the ninth and tenth centuries.

The Beneš decrees differed in validity in Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia because of the legal position of the Slovak National Council (SNR). Some decrees were valid only in Bohemia and Moravia, with the SNR issuing ordinances for Slovakia. In some cases, they had different solutions for the problems of the German and Hungarian minorities.

Overview

Beneš, who was elected president of Czechoslovakia in 1935, resigned after the Munich Agreement in 1938. After the occupation of Czechoslovakia Beneš and other Czech officials emigrated to France, establishing in 1939 the Czechoslovak National Committee to restore Czechoslovakia. The committee's primary task was to establish a Czechoslovak army in France. After the fall of France the committee moved to London, where it became the Interim Czechoslovak Government. The government was recognized by the British government on 21 July 1940 and in 1941 by the U.S. and the USSR.[1]

Beneš returned to his post as president, with the rationale that his 1938 resignation under duress was invalid, and was assisted by the government-in-exile and the State Council. In 1942, the government adopted a resolution that Beneš would remain president until new elections could be held.[1]

Although Beneš alone issued Decree No. 1/1940 (on the establishment of the government), all later decrees were proposed by the government in exile according to the 1920 Czechoslovak constitution and co-signed by the prime minister or a delegated minister. The decrees' validity was subject to later ratification by the National Assembly.[1] Beginning on September 1, 1944 (after the Slovak National Uprising) the Slovak National Council (SNR) held legislative and executive power in Slovakia, later differentiating between statewide acts and other regulations; presidential decrees were valid in Slovakia only if they explicitly mentioned agreement by the SNR.

On 4 March 1945 a new government was created in Košice, Slovakia (recently liberated by the Red Army), consisting of parties united in the National Front and strongly influenced by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. The president's power to enact decrees (as proposed by the government) remained in force until 27 October 1945, when the Interim National Assembly convened.[1]

The decrees may be divided as follows:

|

|

|

Although decrees were not covered by the 1920 constitution, they were considered necessary by the Czechoslovak wartime and postwar authorities. On ratification by the Interim National Assembly, they became binding laws with retroactive validity and attempted to preserve Czechoslovak legal order during the occupation.[1] Most of the decrees were abolished by later legislation (see the list below) or became obsolete by having served their purpose.[1]

List of decrees

Note: This list includes only decrees published in the official Collection of Laws of Czechoslovakia

| No. of the Act in the Collection of Laws |

Name | Field | Content | Status | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/1945 | Constitutional decree of the President concerning new organization of the government and ministries in the interim period Ústavní dekret prezidenta o nové organizaci vlády a ministerstev v době přechodné |

Administration | Establishment of Ministries. | Abolished (Act No. 133/1970 Coll.) |

|

| 3/1945 | Decree of the President amending some clauses of the military criminal code and defense code Dekret prezidenta, kterým se mění a doplňují některá ustanovení vojenského trestního zákona a branného zákona |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 85/1950 Coll.) |

||

| 5/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the invalidity of some transactions involving property rights from the time of loss of freedom and concerning the National Administration of property assets of Germans, Hungarians, traitors and collaborators and of certain organizations and associations Dekret prezidenta o neplatnosti některých majetkově - právních jednání z doby nesvobody a o národní správě majetkových hodnot Němců, Maďarů, zrádců a kolaborantů a některých organizací a ústavů |

Redress of war and occupation Retribution |

Invalidation of any property transfers that took place after 29 September 1938 under duress of occupation or as a consequence of national, racial or political persecution, and return of property to original owners. Establishment of national administration of factories and enterprises owned by "state-unreliable persons" (i.e. those who elected German or Hungarian ethnicity in 1929 census and traitors). |

Obsolete | |

| 8/1945 | Decree of the President concerning donation of real estate to the USSR as an act of gratitude Dekret prezidenta o věnování nemovitostí Svazu sovětských socialistických republik jako projev díků |

Administration | Gift of real estate for the Soviet embassy. | Obsolete | In line with the Yalta Conference, most of Czechoslovakia was liberated by the Soviet army in 1945. |

| 12/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the confiscation and expedited allotment of agricultural property of Germans and Hungarians, as well as traitors and enemies of the Czech and Slovak nation Dekret prezidenta o konfiskaci a urychleném rozdělení zemědělského majetku Němců, Maďarů, jakož i zrádců a nepřátel českého a slovenského národa |

Retribution | Confiscation of agricultural property owned by

|

Obsolete | |

| 16/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the punishment of Nazi criminals, traitors and their helpers and concerning extraordinary peoples' courts Dekret prezidenta o potrestání nacistických zločinců, zrádců a jejich pomahačů a o mimořádných lidových soudech |

Redress of war and occupation | Apart from introducing harsher penalties for crimes committed after 21 May 1938 (e.g. death sentence for serving in enemy army in case of aggravating circumstances, whereas the previously effective 1923 Act had mere life imprisonment as a penalty), the act also criminalized some new actions, e.g.:

Establishes extraordinary courts, to decide cases in senates consisting of a presiding professional judge and four lay judges. No possibility of appeal. Death sentence to be carried out within 2 hours of sentencing, or within 24 hours if the court decides that the execution shall be carried out publicly. |

Abolished (Act No. 33/1948 Coll.) |

|

| 17/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the National Court Dekret prezidenta o Národním soudu |

Redress for war and occupation | The National Court heard trials of Protectorate public figures indicted for crimes under Act No. 16/1945 in senates consisting of 7 persons. No possibility of appeal. Death sentence to be carried out within 2 hours of sentencing, or within 24 hours if the court decides that the execution shall be carried out publicly. | Ineffective | The decree was promulgated, to be effective for a period of one year. |

| 19/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the Collection of Laws and Regulations of the Czechoslovak Republic Dekret prezidenta o Sbírce zákonů a nařízení republiky Československé |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 214/1948 Coll.) |

||

| 20/1945 | Constitutional Decree of the President concerning interim performance of the legislature Ústavní dekret prezidenta o prozatímním výkonu moci zákonodárné |

Redress for war and occupation | Establishes the authority of the President, subject to consent of the Government, to enact binding laws in the form of decrees for as long as the Parliament cannot perform its function. | Ineffective | Promulgated on 15 November 1940 in London, published in the collection as Act No. 20/1945 Coll. |

| 21/1945 | Constitutional Decree of the President concerning performance of the legislature in the interim period Ústavní dekret prezidenta o výkonu moci zákonodárné v přechodném období |

Redress for war and occupation | Prolongation of effectiveness of Act No. 20/1945 Coll. until the Interim National Assembly convenes. | Ineffective | Promulgated on 5 March 1945, rendered ineffective by the first convention of the Interim National Assembly on 28 October 1945. |

| 22/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the promulgation of laws promulgated outside of the Czechoslovak territory Ústavní dekret prezidenta o vyhlášení právních předpisů, vydaných mimo území republiky Československé |

Redress for war and occupation | Authorization of the Government to decide which of the laws promulgated during the time of exile in London shall be re-printed in the official collection of laws and remain in force. | Obsolete | |

| 25/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the unification of tax legislation within the Czechoslovak Republic Dekret prezidenta o sjednocení celního práva na území republiky Československé |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 36/1953 Coll.) |

||

| 26/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the repeal of the Act of 9 July 1945 Dekret prezidenta o zrušení zákona ze dne 9. července 1945 |

Administration | Repeal of Act No. 165/1934 Coll., on retirement of judges according to their age. | Obsolete | According to Act No. 165/1934 Coll., judges were to retire at age 65. German Nazi extermination of many Czechoslovak judges led to need for longer service by those remaining. |

| 27/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the unified management of internal settlement Dekret prezidenta o jednotném řízení vnitřního osídlení |

Retribution Administration |

Legal framework for measures for the "return of all areas of the Czechoslovak republic to the original Slavic inhabitants." | Abolished (Act No. 18/1950 Coll.) |

Concerns not only the Czechs and Slovaks expelled by the Germans and Hungarians from the borderlands following the Munich Agreement and First Vienna Award. |

| 28/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the settlement of Czech, Slovak or other Slavic farmers on the agricultural land of Germans, Hungarians and other enemies of the state Dekret prezidenta o osídlení zemědělské půdy Němců, Maďarů a jiných nepřátel státu českými, slovenskými a jinými slovanskými zemědělci. |

Retribution Administration |

Distribution of land which had not previously been distributed under Act No. 12/1945 Coll., to politically and nationally reliable Czechs, Slovaks and other Slavs. | Obsolete | |

| 33/1945 | Constitutional Decree of the President concerning modification of Czechoslovak citizenship of persons of German and Hungarian ethnicity Ústavní dekret prezidenta o úpravě československého státního občanství osob národnosti německé a maďarské |

Retribution | Czechoslovak citizens of German or Hungarian ethnicity

The decree does not concern Germans and Hungarians who

This was reviewed by the Ministry of Interior; or in cases of German/Hungarian soldiers serving in the Czechoslovak army abroad, by Ministry of Defense, with presumption of fulfillment of the conditions. Czechs and Slovaks who elected German/Hungarian nationality under duress may request exemption by Ministry of Interior. Married women and children to be assessed individually. |

Obsolete | Germans and Hungarians carried the burden of proof that they had remained loyal to the Republic (unless they were members of the Czechoslovak army abroad or elected Czech or Slovak nationality during the occupation). Under Art. 3 of the Act, those who lost Czechoslovak citizenship could request its restoration within 6 months of promulgation of the Act. The request was to be decided by the Ministry of Interior. Later, in 1948, Regulation No. 76/1948 Coll. was adopted, under which the period for request was prolonged for 3 years. The Ministry of Interior was bound to restore applicant's citizenship unless it could determine the applicant had breached their "duties of Czechoslovak citizen". |

| 35/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the interim limitation of payment of deposits by banks and financial institutions in the borderlands Dekret prezidenta o přechodném omezení výplat vkladů u peněžních ústavů (peněžních podniků) v pohraničním území |

Retribution Administration |

Prohibition of payouts or transfers to Germans and Hungarians by Czechoslovak or German/Hungarian banks in the borderlands (with exception of those Germans/Hungarians who remained loyal to the Czechoslovak Republic, had not committed offenses against the Czech or Slovak nation and had either taken part in the liberation of Czechoslovakia or were subject to Nazi or fascist terror). | Obsolete | |

| 36/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the fulfillment of obligations made in Reichsmarks Dekret prezidenta o plnění závazků znějících na říšské marky |

Redress for war and occupation | Obligations in Reichsmarks owed by persons or corporations having seat/residence in the Czech lands shall be paid in korunas at the exchange rate 1 Reichsmark = 10 Koruna. | Obsolete | |

| 38/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the severe punishment of looting Dekret prezidenta o přísném trestání drancování |

Administration | 5–10 years (10-20 or life in case of aggravating circumstances) of imprisonment for looting, possibility of enacting martial law in case of widespread looting. | Abolished (Act No. 86/1950 Coll.) |

|

| 39/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the repeal of the Act of 9 July 1945 Dekret prezidenta o dočasné příslušnosti ve věcech náležejících soudům porotním a kmetským |

Administration | Until the end of 1945, panels of 4 judges were to decide criminal cases where otherwise jury trials were appropriate. | Obsolete | |

| 47/1945 | Constitutional decree of the President concerning Interim National Assembly Ústavní dekret prezidenta o Prozatímním Národním shromáždění |

Redress for war and occupation | Establishment of the Interim National Assembly for the period until the National Assembly is elected in the general elections. | Abolished (Act No. 65/1945 Coll.) |

Interim National Assembly consisted of 200 Czechs and 100 Slovaks elected by electors, who had been elected by local National Committees. Slovak deputies had veto power over issues concerning Slovakia. |

| 50/1945 | Decree of the President concerning measures for the film industry Dekret prezidenta o opatřeních v oblasti filmu |

Nationalization | Nationalization of cinematic industry, prohibition of filming and public screening.. | Partially abolished, obsolete | Prohibition of filming and public screening abolished from 28 August 1945. |

| 52/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the interim management of the national economy Dekret prezidenta o zatímním vedení státního hospodářství |

Administration | Use of public assets before the State Budget is approved by the National Assembly. | Abolished (Act No. 160/1945 Coll.) |

|

| 53/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the redress of grievances of Czechoslovak public employees Dekret prezidenta o odčinění křivd československým veřejným zaměstnancům |

Redress for war and occupation | Redress for public employees who were persecuted by the Nazi and/or occupation authorities for their political opinions or personal characteristics (e.g. Jews, former Czechoslovak legionaries in WW1, masons, etc.) and other victims of persecution (e.g. victims of Nazi terror, Nazis' hostages, University professors, etc.). | Obsolete | |

| 54/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the registration of wartime damages and damages caused by exceptional circumstances Dekret prezidenta o přihlašování a zjišťování válečných škod a škod způsobených mimořádnými poměry |

Administration | Registration of damages caused by war operations, by occupation authorities or by others acting on their orders, due to persecution on political, national or racial grounds, or by terrorist actions of the enemy states or persons dangerous to the public. | Obsolete | Registration had to be made within 21 days from promulgation of the enactment. |

| 56/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the modification of the wage of the President of the Czechoslovak Republic Dekret prezidenta o úpravě platu prezidenta Československé republiky |

Administration | Annual wage of 3.300.000 koruna and office expenses of 3.000.000 koruna. | Abolished (Act No. 10/1993 Coll.) |

|

| 57/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the wage and acting and representative allowance of the members of the Government Dekret prezidenta o platu a o činovním a representačním přídavku členů vlády |

Administration | Annual wage of the Prime Minister 120.000 koruna, Vice-Prime Minister 100.000 koruna, Ministers 80.000 koruna. | Abolished (Act No. 110/1960 Coll.) |

|

| 58/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the wage increase of state and other public employees Dekret prezidenta o platovém přídavku státním a některým jiným veřejným zaměstnancům |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 66/1958 Coll.) |

||

| 59/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the cancellations of appointments of public employees during the time of oppression Dekret prezidenta, jímž se zrušují jmenování veřejných zaměstnanců z doby nesvobody |

Redress for war and occupation | Cancellation of appointments of employees of the state, regional and municipal administrations, public corporations and publicly owned companies, as well as teachers. | Abolished (Act No. 86/1950 Coll.) |

|

| 60/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the preparations to execute the Treaty between the Czechoslovak Republic and USSR on Carpathian Ruthenia Ústavní dekret prezidenta o přípravě provedení smlouvy mezi Československou republikou a Svazem sovětských socialistických republik o Zakarpatské Ukrajině ze dne 29. června 1945 |

Administration | Governmental authority to execute treaty of 29 June 1945, especially concerning ability of people living in Carpathian Rutheania to opt for Czechoslovak citizenship, derogation of constitutional rights in breach of the treaty. | Abolished (Act No. 186/1946 Coll.) |

Carpathian Ruthenia was the easternmost part of the Czechoslovak Republic which became part of USSR after WW2; today it is part of Ukraine. |

| 62/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the easement in the criminal trials Dekret prezidenta o úlevách v trestním řízení soudním |

Administration | Among many other changes, appellate courts to act in panels consisting of three judges instead of previous 5, possibility of stopping criminal proceedings where the penalty would me minor compared to a sentence which the defendant is already serving, etc. | Abolished (Act No. 87/1950 Coll.) |

|

| 63/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the Economic Council Dekret prezidenta o Hospodářské radě |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 60/1949 Coll.) |

||

| 66/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the Official List of the Czechoslovak Republic Dekret prezidenta o Úředním listě republiky Československé |

Administration | Regulations and Directives that were not promulgated in the Collection of Laws were promulgated in the Official List.. | Abolished (Act No. 260/1949 Coll.) |

|

| 67/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the restoration of functioning of disciplinary and qualification commissions for public employees and concerning abolishment of regulations on limitation of appeals Dekret prezidenta, jímž se obnovuje činnost disciplinárních a kvalifikačních komisí pro veřejné zaměstnance a zrušují se předpisy o omezení opravných prostředků |

Redress for war and occupation | Abolished (Act No. 66/1950 Coll.) |

||

| 68/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the reactivation of public employees Dekret prezidenta o reaktivaci veřejných zaměstnanců |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 66/1950 Coll.) |

Public employees on pension to be recalled to service where needed. | |

| 69/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the relocation of the Technical University from Příbram to Ostrava Dekret prezidenta o přeložení vysoké školy báňské z Příbrami do Moravské Ostravy |

Administration | Valid | The Technical University was established in 1849 in Příbram and closed by the German Nazis in 1939; by 1945, Ostrava had become the mining and metallurgical center of the region. | |

| 71/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the work duty of persons that had lost Czechoslovak citizenship Dekret prezidenta o pracovní povinnosti osob, které pozbyly československého státního občanství |

Redress for war and occupation | Work duty on repairing war damage; besides Germans and Hungarians who had lost citizenship, concerns also Czechs and Slovaks who had, unless under duress, applied for German or Hungarian citizenship during the occupation. Work duty is subject to remuneration. | Abolished (Act No. 66/1965 Coll.) |

See also Act No. 88/1945 Coll., lower, establishing universal work duty notwithstanding ethnicity or collaboration. |

| 73/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the change of the wage act of 24 June 1926 No. 103 Coll, as regards University Professors and Assistants Dekret prezidenta, kterým se mění a doplňuje platový zákon ze dne 24. června 1926, č. 103 Sb., pokud jde o profesory vysokých škol a vysokoškolské asistenty |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 66/1958 Coll.) |

||

| 74/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the reactivation and reappointment of married women in the public service Dekret prezidenta o reaktivaci a o opětném ustanovení provdaných žen ve veřejné službě |

Redress for war and occupation | Occupation Governmental Regulation No. 379/1938 Coll. led to termination of married women from public jobs. Under the decree, these women may request reappointment within 6 months of its promulgation. | Abolished (Act No. 66/1950 Coll.) |

See also: Women in Nazi Germany |

| 76/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the call for means of transport for the period of exceptional economical circumstances Dekret prezidenta o požadování dopravních prostředků po dobu mimořádných hospodářských poměrů |

Administration | Local authorities may request means of transport (horses, cars) from private owners for important reasons, e.g. harvest, coal delivery, etc. | Abolished (Act No. 57/1950 Coll.) |

Public distribution system was in place after the war. |

| 77/1945 | Decree of the President concerning some measures for the acceleration of loading and unloading of goods transported by rail Dekret prezidenta o některých opatření k urychlení nakládky a vykládky zboží v železniční dopravě |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 36/1966 Coll.) |

||

| 78/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the interim financial securing of business companies Dekret prezidenta o přechodném finančním zabezpečení hospodářských podniků |

Redress for war and occupation | Abolished (Act No. 36/1966 Coll.) |

||

| 79/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the interim adjustment of judiciary in the Bohemian and Moravian-Silesian lands Dekret prezidenta o zatímní úpravě soudnictví v zemích České a Moravskoslezské |

Redress for war and occupation | Restoration of Czech judicial regions as they were prior to the Munich Agreement, abolition of German judiciary within the Czech lands. | Obsolete | Czechoslovakia was administratively divided into lands: Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia; the decree concerns only the former two, which were occupied by Germany. Moreover, Slovakia, being part of Hungary prior to 1918, had a different legal system stemming from Hungarian common law. |

| 80/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the reintroduction of Central European Time Dekret prezidenta o opětném zavedení středoevropského času |

Redress for war and occupation | Reintroduction of Central European Time, elimination of Central European Summer Time introduced by the Nazis. | Obsolete | Today, the Czech Republic uses Central European Summer Time. |

| 81/1945 | Decree of the President concerning some measures in the area of associations Dekret prezidenta o některých opatřeních v oboru spolkovém |

Redress for war and occupation | Cancellation of regulations and measures of the occupation authorities leading to dissolution of associations. | Abolished (Act No. 150/1945 Coll.) |

|

| 82/1945 | Decree of the President concerning advance payments for some wartime damages Dekret prezidenta o zálohách na náhradu za některé válečné škody majetkové |

Redress for war and occupation | Concerns advance payments for wartime damages to socially poor persons. | Abolished (Act No. 161/1946 Coll.) |

At the time of promulgation, it was not known that Germany would never repay any war damages. |

| 83/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the military obligations of conscripts as well as soldiers who entered military voluntarily Dekret prezidenta o úpravě branné povinnosti osob povolaných, jakož i dobrovolně nastoupivších do činné služby |

Administration | Concerns especially soldiers fighting with Czechoslovak army units abroad or partisans. These were considered to be conscripted as of the day of joining the respective unit. | Valid, effective | |

| 84/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the interim adjustment of length of conscription Dekret prezidenta o přechodné úpravě délky presenční služby |

Administration | Concerns soldiers conscripted prior to the occupation or during occupation (the latter especially in Slovakia). | Obsolete | Czechoslovak army was dissolved during the occupation; soldiers who had not served their full terms had to re-enlist for a defined period of time. |

| 85/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the abolition of tuition at state secondary schools Dekret prezidenta, kterým se ruší školné na státních středních školách |

Administration | Abolishes tuition at secondary state schools introduced by regulation No. 161/1926 Coll. (It had not applied to those who could not afford it.) | Obsolete | Today, the right to free elementary and secondary education is enshrined in Article 33 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms of the Czech Republic. |

| 86/1945 | Decree of the President concerning rebuilding of Financial Guard in the Bohemian and Moravian-Silesian lands and on adjustment of some duty and wage issues of members of the Financial Guard Dekret prezidenta o znovuvybudování finanční stráže v zemích České a Moravskoslezské a o úpravě některých služebních a platových poměrů příslušníků finanční stráže |

Redress for war and occupation | Reinstatement of the Financial Guard and reappointment of its members, appointment of its 1938 cadets (with remission of entrance exams). | Obsolete | Occupation forces had established customs union between Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and Germany and had dissolved Czech Financial Guard (Slovakia had become independent state with its own Financial Guard). |

| 88/1945 | Decree of the President concerning universal work duty Dekret prezidenta o všeobecné pracovní povinnosti |

Redress for war and occupation | Any person may be called to perform work duty which is in public interest for maximum period of one year. Work duty subject to remuneration. | Abolished (Act No. 66/1965 Coll.) |

|

| 89/1945 | Decree of the President concerning honors for merit in building the state and for extraordinary work performance Dekret prezidenta o vyznamenáních za zásluhy o výstavbu státu a za vynikající pracovní výkony |

Administration | Assigning of distinctions in the field of economy, science or culture for extraordinary merit in building the state or for extraordinary work performance. | Obsolete | Follows Soviet model: honorary titles such as "Hero of Work", "Work Fighter", badges, etc. |

| 90/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the adjustment of organizational and duty issues in the judiciary Dekret prezidenta o úpravě některých organisačních a služebních otázek v oboru soudnictví |

Administration | Division of judiciary, judges' wages, organization of courts, etc. | Abolished (Act No. 66/1952 Coll.) |

|

| 91/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the restoration of the Czechoslovak currency Dekret prezidenta o obnovení československé měny |

Redress for war and occupation | Reinstatement of Czechoslovak koruna as the country's currency from 1 November 1945. | Obsolete | |

| 93/1945 | Decree of the President concerning interim measures in the area of public social insurance Dekret prezidenta o prozatímních opatřeních v oboru veřejno-právního sociálního pojištění |

Redress for war and occupation | Authorization for the Minister of Work and Welfare to undertake measures in the field necessitated by the wartime occupation (i.e. authority of welfare offices, organizational and administrative measures in the border areas, etc.). | Abolished (Act No. 99/1948 Coll.) |

|

| 94/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the adjustment of some issues of organization and duty and wages of uniformed prison service Dekret prezidenta o úpravě některých otázek organisace a služebních a platových poměrů sboru uniformované vězeňské stráže |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 321/1948 Coll.) |

In many prisons, Czech prison guards had been replaced by Waffen SS and Gestapo torturers during the occupation. | |

| 95/1945 | Decree of the President concerning registraton of bank deposits and other financial obligation by financial institutions, as well as life insurance and securities Dekret prezidenta o přihlášení vkladů a jiných peněžních pohledávek u peněžních ústavů, jakož i životních pojištění a cenných papírů |

Administration | Inter alia, duty of registration of anonymous passbooks in owners' own names. | Obsolete | III. ÚS 462/98 |

| 96/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the establishment of branch of Medical Faculty of Charles University in Hradec Králové Dekret prezidenta o zřízení pobočky lékařské fakulty University Karlovy v Hradci Králové |

Administration | Obsolete | The branch became the Army Medical Academy in 1951 and a Medical Faculty of Charles University in its own right in 1958. Today it provides, inter alia, training for military doctors. | |

| 97/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the amendments to special income taxes Dekret prezidenta, kterým se mění a doplňují ustanovení o zvláštní dani výdělkové |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 78/1952 Coll.) |

||

| 98/1945 | Decree of the President concerning interim measures in the area of turnover taxes Dekret prezidenta o přechodných opatřeních v oboru daně z obratu |

Administration | Amendment of regulations No. 314/1940 Coll., No. 315/1940 Coll., No. 390/1941 Coll. and other regulations and directives. | Obsolete | |

| 99/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the adjustment of direct taxes for calendar years 1942 through 1944 and on adjustment of fees and business charges Dekret prezidenta o úpravě přímých daní za kalendářní roky 1942 až 1944 a o úpravě poplatků a daní obchodových |

Redress for war and occupation | Valid | ||

| 100/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the nationalization of mines and some industrial enterprises Dekret prezidenta o znárodnění dolů a některých průmyslových podniků |

Nationalization | Nationalization of mines and industrial enterprises in the fields of energy, metallurgy, armaments, chemicals, and others (altogether 27 fields, in some only enterprises having a defined number of employees, e.g. paper plants with more than 150, etc.). Nationalization is subject to remuneration, with exception of former owners being:

|

Nationalization obsolete Remuneration valid and effective |

Subject of many contemporary court decisions, especially in proceedings whereby descendants of former owners are attempting to prove that their ancestors fulfilled the requirements of remuneration in cases where authorities in 1940s and 1950s did not consider the ancestors loyal to the Republic and/or subject to Nazi terror. |

| 101/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the nationalization of some enterprises in the food industry Dekret prezidenta o znárodnění některých podniků průmyslu potravinářského |

Nationalization | Nationalization of sugar mills and refineries, industrial distilleries, large breweries, large mills, factories producing artificial fat, large chocolate factories. Subject to renumeration under conditions of Act No. 100/1945 Coll. | Nationalization obsolete Remuneration valid and effective |

Subject of many contemporary court decisions, especially in proceedings whereby descendants of former owners are attempting to prove that their ancestors fulfilled the requirements of remuneration in cases where authorities in 1940s and 1950s did not consider the ancestors loyal to the Republic and/or subject to Nazi terror. |

| 102/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the nationalization of banks Dekret prezidenta o znárodnění akciových bank |

Nationalization | Nationalization of shares of the banks, subject to remuneration under similar conditions to those in Act. No. 100/1945 Coll. | Obsolete | |

| 103/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the nationalization of private insurers Dekret prezidenta o znárodnění soukromých pojišťoven |

Nationalization | Obsolete | ||

| 104/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the plant and factory councils Dekret prezidenta o závodních a podnikových radách |

Administration | Basis for establishment of de facto unions at factories. | Abolished (Act No. 37/1959 Coll.) |

|

| 105/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the cleansing commissions for reevaluation of actions of public employees Dekret prezidenta o očistných komisích pro přezkoumání činnosti veřejných zaměstnanců |

Redress for war and occupation | Punishment (ranging from rebuke to sacking from job) for registering German or Hungarian ethnicity, political cooperation with Germans or Hungarians (especially in Germanic societies), propagation or approval of fascism or antisemitism, etc. | Abolished (Act No. 36/1966 Coll.) |

Subject of many contemporary court decisions, especially in proceedings whereby descendants of former owners are attempting to prove that their ancestors fulfilled the requirements for remuneration in cases where authorities in 1940s and 1950s did not consider the ancestors loyal to the Republic and/or subject to Nazi terror. |

| 106/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the wages of the interim National Assembly Dekret prezidenta o platech členů Prozatímního Národního shromáždění |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 62/1954 Coll.) |

||

| 107/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the interim adjustment of fee equivalent in the Bohemian and Moravian-Silesian lands Dekret prezidenta o přechodné úpravě poplatkového ekvivalentu v zemích České a Moravskoslezské |

Administration | Real estate tax | Abolished (Act No. 159/1949 Coll.) |

|

| 108/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the confiscation of enemy property and on the Fund for National Restoration Dekret prezidenta o konfiskaci nepřátelského majetku a Fondech národní obnovy |

Retribution Redress for war and occupation |

Nationalization of remaining property of:

Establishment of the Fund for National Restoration. |

Nationalization obsolete Fund abolished |

Subject of many contemporary court decisions, especially in proceedings whereby descendants of former owners are attempting to prove that their ancestors fulfilled the requirements for remuneration in cases where authorities in 1940s and 1950s did not consider the ancestors loyal to the Republic and/or subject to Nazi terror. |

| 109/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the management of production Dekret prezidenta o řízení výroby |

Administration | Minister of Industry may issue Directives in order to safeguard functioning of enterprises and provisioning of population. | Abolished (Act No. 36/1966 Coll.) |

|

| 110/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the organization of peoples' and art production Dekret prezidenta o organisaci lidové a umělecké výroby |

Nationalization | Abolished (Act No. 56/1957 Coll.) |

||

| 112/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the administration of remand prisons and criminal institutions Dekret prezidenta o správě soudních věznic a trestních ústavů |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 319/1948 Coll.) |

||

| 113/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the adjustment, management and control of foreign trade Dekret prezidenta o úpravě, řízení a kontrole zahraničního obchodu |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 31/1964 Coll.) |

||

| 114/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the establishment of new directorates of posts and on adjustment of districts of post directorates in the lands of Bohemia and Moravia-Silesia Dekret prezidenta o zřízení nových ředitelství pošt a o úpravě obvodů ředitelství pošt v zemích České a Moravskoslezské |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 31/1964 Coll.) |

||

| 115/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the management of coal and firewood Dekret prezidenta o hospodaření uhlím a palivovým dřívím |

Administration | Establishment of central authority for management of coal and firewood. | Obsolete | |

| 116/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the amendment of act of 25 July 1926 No. 122/1928 Coll, on adjustment of wages of priests of churches and religious societies officially recognized by the state Dekret prezidenta o změně zákona ze dne 25. června 1926, č. 122 Sb. a vlád. nařízení ze dne 17. července 1928, č. 124 Sb., o úpravě platů duchovenstva církví a náboženských společností státem uznaných případně recipovaných, a o platovém přídavku k nejnižšímu ročnímu příjmu duchovenstva |

Administration | Obsolete | ||

| 117/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the adjustment of provisions regulating the declaration of death Dekret prezidenta, kterým se upravují ustanovení o prohlášení za mrtvého |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 142/1950 Coll.) |

||

| 118/1945 | Decree of the President concerning measures regarding nutrition management Dekret prezidenta o opatřeních v řízení vyživovacího hospodářství |

Administration | Minister of Nutrition may manage purchase, processing and use of goods in order to secure nutrition of population. | Abolished (Act No. 36/1966 Coll.) |

|

| 119/1945 | Decree of the President concerning interim adjustment of military criminal code Dekret prezidenta o přechodné úpravě vojenského trestního řádu |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 226/1947 Coll.) |

||

| 120/1945 | Decree of the President concerning interim adjustment of military field trials Dekret prezidenta o přechodné úpravě vojenského polního trestního řízení |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 226/1947 Coll.) |

||

| 121/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the territorial organization of administration performed by national committees Dekret prezidenta o územní organisaci správy, vykonávané národními výbory |

Redress for war and occupation | Reestablishment of regional and municipal self-government as it existed prior to the occupation. | Abolished (Act No. 36/1960 Coll.) |

|

| 122/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the abolition of the German University in Prague Dekret prezidenta o zrušení německé university v Praze |

Retribution | Abolition of the German University in Prague, which had ceased functioning on 5 May 1945 due to the Prague uprising. | Valid and effective | Retroactively effective as of 17 November 1939. |

| 123/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the abolition of German Institutes of Technology in Prague and Brno Dekret prezidenta o zrušení německých vysokých škol technických v Praze a v Brně |

Retribution | Obsolete | Retroactively effective as of 17 November 1939. | |

| 124/1945 | Decree of the President concerning some measures on the issue of public registers Dekret prezidenta o některých opatřeních ve věcech knihovních |

Redress for war and occupation | Where Germany, Hungary, or German or Hungarian corporations had obtained ownership by inscribing into the public registry anything that had previously belonged to Czechoslovakia, Czech lands or corporations owned or administered by them, the original inscription was to be reinstated. | Obsolete | |

| 125/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the establishment of the Conscription Union Dekret prezidenta o zřízení Svazu brannosti |

Administration | Conscription Union provides training of conscripts. | Abolished (Act No. 138/1949 Coll.) |

|

| 126/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the special forced work units Dekret prezidenta o zvláštních nucených pracovních oddílech |

Administration | Establishment of work units at prisons. Convicts' remuneration shall be forfeited by the state. | Abolished (Act No. 87/1950 Coll.) |

|

| 127/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the establishment of Academy of Performing Arts in Prague Dekret prezidenta o zřízení vysoké školy "Akademie musických umění v Praze" |

Administration | Establishment of Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. | Valid and effective | |

| 128/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the interim territorial organization of some financial offices and on other associated changes Dekret prezidenta o zatímní územní organisaci některých finančních úřadů a změnách s tím spojených v zemích České a Moravskoslezské |

Redress for war and occupation | Restoration of Financial Offices (tax revenue offices) as they had been prior to the occupation. | Obsolete | |

| 129/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the establishment of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Dekret prezidenta o státním orchestru Česká filharmonie |

Administration | Establishment of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra. | Valid and effective | |

| 130/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the public enlightenment care Dekret prezidenta o státní péči osvětové |

Administration | Abolished (Act No. 52/1959 Coll.) |

||

| 131/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the building of the Academy House - Memorial to the 17th November Dekret prezidenta o vybudování Akademického domu - Památníku 17. listopadu |

Redress for war and occupation | Obsolete | Building at Spálená 12, today the Municipal Polyclinic of Prague. | |

| 132/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the education of teachers Dekret prezidenta o vzdělání učitelstva |

Administration | Compulsory University education of schoolteachers. | Abolished (Act No. 36/1966 Coll.) |

|

| 133/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the establishment of the Scientific Pedagogical Institute of Jan Amos Komenský Dekret prezidenta, kterým se zřizuje Výzkumný ústav pedagogický Jana Amose Komenského |

Nationalization | Obsolete | Today the National Institute for Education. | |

| 135/1945 | Decree of the President concerning establishment of branch of Medical Faculty of Charles University in Plzeň Dekret prezidenta o zřízení pobočky lékařské fakulty university Karlovy v Plzni |

Administration | Obsolete | Today a faculty of Charles University in its own right. | |

| 137/1945 | Constitutional Decree of the President concerning the remand of persons who were considered unreliable during the time of revolution Ústavní dekret prezidenta o zajištění osob, které byly považovány za státně nespolehlivé, v době revoluční |

Redress for war and occupation | Legalization of remand of persons during the anti-nazi revolution (remand would otherwise require court order, and extrajudicial remand could lead to criminal responsibility of the persons responsible and the right of compensation for those remanded). | Abolished (Act No. 87/1950 Coll.) |

|

| 138/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the punishment of some offenses against the national honor Dekret prezidenta o trestání některých provinění proti národní cti |

Administration | Administrative punishment for "improper behavior offending the national feelings of Czech or Slovak people leading to public indignation" in the time after 21 May 1938 (up to one year imprisonment, fine). | Obsolete | |

| 139/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the interim adjustment of legal relations of the Czechoslovak National Bank Dekret prezidenta o přechodné úpravě právních poměrů Národní banky Československé |

Redress for war and occupation | Introduces, inter alia, interim administration of the National Bank. | Abolished (Act No. 38/1948 Coll.) |

|

| 140/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the establishment of the College of Political and Social Arts in Prague Dekret prezidenta o zřízení Vysoké školy politické a sociální v Praze |

Administration | Obsolete | ||

| 143/1945 | Decree of the President concerning the limitation of the right of prosecution in criminal proceedings Dekret prezidenta o omezení žalobního práva v trestním řízení |

Retribution | Persons whose property was nationalized under Act No. 108/1945 Coll., and whose honor was harmed may not initiate criminal proceedings against the offender under the respective statute themselves but may only request the State Attorney to do so. | Abolished | The Decree itself set its validity only until 31 December 1946 |

Loss of citizenship and confiscation of property

Legal basis for expulsions

The Beneš decrees are associated with the 1945-47 deportation of about 3 million ethnic Germans and Hungarians from Czechoslovakia. The deportation, based on Article 12 of the Potsdam Agreement, was the outcome of negotiations between the Allied Control Council and the Czechoslovak government.[1] The expulsion is considered ethnic cleansing (a term in widespread use since the early 1990s)[3][4] by a number of historians and legal scholars.[4][5][6][7][8] The relevant decrees omit any reference to the deportation.[9]

Of the allies, the Soviet Union urged Great Britain and the U.S. to agree to the transfer of ethnic Germans and German-speaking Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, Yugoslavs and Romanians into their zones of occupation. France, which was not a party to the Potsdam Agreement, did not accept exiles in its zone of occupation after July 1945. Most ethnic-German Czechoslovak citizens had supported the Nazis through the Sudeten German Party (led by Konrad Henlein) and the 1938 German annexation of the Sudetenland.[10] Most ethnic Germans failed to follow the mobilization order when Czechoslovakia was threatened with war by Hitler in 1938, crippling the army's defensive capabilities.

Decree subjects

In general, the decrees dealt with loss of citizenship and confiscation of the property of:

- Art 1(1): Germany and Hungary, or companies incorporated in Germany or Hungary and selected entities (e.g. NSDAP)

- Art 1(2): Those who applied for German or Hungarian citizenship during the occupation and specified German or Hungarian ethnicity in the 1929 census

- Art 1(3): Those who acted against the sovereignty, independence, integrity, democratic and republican organization, safety and defense of the Czechoslovak Republic, incited such acts or intentionally supported the German or Hungarian occupiers (Polish occupiers were omitted)

The defining character in definition of the entities affected was their hostility to the Czechoslovak Republic and to the Czech and Slovak nations. The hostility presumption was irrebuttable in case of entities in the Art.1(1), while it is rebuttable under Art.1(2) in case of physical persons of German or Hungarian ethnicity, i.e. that they were exempted under Decrees 33 (loss of citizenship), 100 (nationalization of large enterprises without renumeration) and 108 (expropriation) where they proved that they remained loyal to the Czechoslovak Republic, they didn't commit an offense against the Czech and Slovak nation, and that they had either actively participated in liberation of Czechoslovakia or were subjected to Nazi or fascist terror. At the same time, Art 1(3) covered any persons notwithstanding ethnicity, including Czechs and Slovaks.

Some 250,000 Germans, some anti-fascists exempted under the Decrees and others considered crucial to industry, remained in Czechoslovakia. Many ethnic German anti-fascists emigrated under an agreement drawn up by Alois Ullmann.

Regaining Czechoslovak citizenship

Loss of Czechoslovak citizenship was addressed in Decree 33 (see description above). Under article three of the decree, those who lost their citizenship could request its restoration within six months of the decree's promulgation and requests would be assessed by the Interior Ministry.

On April 13, 1948 the Czechoslovak government issued Regulation 76/1948 Coll., lengthening the window for requesting reinstatement of Czechoslovak citizenship under Decree 33 to three years. Under this regulation, the Interior Ministry was bound to restore an applicant's citizenship unless it could determine that they had breached the "duties of a Czechoslovak citizen"; the applicant may had been requested also to prove "adequate" knowledge of Czech or Slovak language.[11]

On 25 October Act 245/1948 Coll. was adopted, in which ethnic Hungarians who were Czechoslovak citizens on 1 November 1938 and lived in Czechoslovakia at the time of the act's promulgation could regain Czechoslovak citizenship if they pledged allegiance to the Republic within 90 days. Taking the oath would, according to the German laws valid at the time, automatically lead to loss of German citizenship.[12]

On 13 July 1949, Act 194/1949 Coll. was adopted. Under article three of the act, the Interior Ministry could bestow citizenship on applicants who had not committed an offense against Czechoslovakia or the people's democracy, had lived in the country for at least five years, and who would lose their other citizenship by receiving the Czechoslovak one.

On 24 April 1953, Act 34/1953 Coll. was adopted. Under this act, ethnic Germans who lost Czechoslovak citizenship under Decree 33 and were living in Czechoslovakia on the day of the act's promulgation automatically regained their citizenship. This also applied to spouses and children living in Czechoslovakia with no other citizenship.

For comparison, any person may currently be granted Czech citizenship if they:[13]

- Have been granted long-term residence and have been living in the country for at least five years, and

- Have not been found guilty of a criminal offense in the past five years, and

- Demonstrate knowledge of the Czech language, and

- Fulfill the legal requirements of the Czech Republic, such as paying taxes and obtaining health insurance

Restitution of property

After the Velvet Revolution Act 243/1992 Coll. was adopted, arranging restitution of real estate taken by the decrees or lost during the occupation. The act applied to:

- Citizens of the Czech Republic (or their descendants) who:

- Lost their property after the communist coup of 25 February 1948 (loss of title to the property was entered into the land registry after this date) on the basis of decrees 12 (confiscation of agricultural property) or 108 (general confiscation), and

- Regained Czechoslovak citizenship under Decree 33 or Acts 245/1948, 194/1949 or 34/1953 Coll. and had not lost their citizenship by 1 January 1990, and

- Had not committed an offense against Czechoslovakia.

- Claims could be made until 31 December 1992 by those living in the Czech Republic and until 15 July 1996 by those living abroad.

- Citizens of the Czech Republic (or their descendants) who lost their property during the occupation, were entitled to its restitution under decrees 5 and 128 and had not been compensated (e.g. Jews); claims could be made until 30 June 2001.

Current status

United Nations

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

In 2010 the United Nations Human Rights Committee, under the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, reviewed a communication submitted by Josef Bergauer et al. The committee held that the covenant became effective in 1975 and its protocol in 1991. Since the covenant could not be applied retroactively, the committee held that the communication was inadmissible.[14]

Restitution legislation

After the Velvet Revolution Czechoslovakia also adopted Act 87/1991 Coll., providing restitution or compensation to victims of confiscation for political reasons during the Communist regime (25 February 1948 – 1 January 1990). The law also provided for restitution or compensation to victims of racial persecution during World War II who are entitled by Decree 5/1945.

In 2002 the UN Human Rights Committee stated its views in Brokova v. The Czech Republic, in which the applicant was refused restitution of property nationalized under Decree 100 (nationalization of large enterprises). Brokova was excluded from restitution, although the Czech nationalization in 1946–47 could only be implemented because the author's property had been confiscated during the German occupation. In the committee's view, this was discriminatory treatment of the plaintiff compared to those whose property was confiscated by Nazi authorities and not nationalized immediately after the war (and who, therefore, could benefit from the laws of 1991 and 1994). The committee found that Brokova was denied her right to equal protection under the law, in violation of article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[15]

European Court of Human Rights

In 2005, the European Court of Human Rights refused the application of Josef Bergauer and 89 others against the Czech Republic. According to the applicants, "after the Second World War, they were expelled from their homeland in genocidal circumstances", their property was confiscated by Czechoslovak authorities, the Czech Republic failed to suspend the Beneš Decrees and had not compensated them. The court held that the expropriation took place long before the implementation of the European Convention on Human Rights with respect to the Czech Republic. Since Article 1 of Protocol 1 does not guarantee the right to acquire property, although the Beneš Decrees remained part of Czech law the applicants had no claim under the convention against the Czech Republic to recover the confiscated property. According to the court, "it should be further noted that the case-law of the Czech courts made the restitution of property available even to persons expropriated contrary to the Presidential Decrees, thus providing for the reparation of acts which contravened the law then in force. The Czech judiciary thus provides protection extending beyond the standards of the Convention."[16]

Czech Republic

Review by the Czech Constitutional Court

Validity of the decrees

The validity of the Beneš decrees was first reviewed at the plenary session of the Czech Constitutional Court in its decisions of 8 March 1995, published as Decisions No. 5/1995 Coll. and 14/1995 Coll. The court addressed the following issues concerning the decrees' validity:

- Conformity of the decree process with the Czechoslovak law and the 1920 Constitution:

The Constitutional Court is of the opinion that the Interim Czechoslovak Government, as established in the United Kingdom, must be viewed as internationally accepted legitimate constitutional body of the Czechoslovak country, whose territory was occupied by the German army. The enemy compromised possibility of performance of the sovereign Czechoslovak powers, as they enshrine in the Czechoslovak constitution and the Czechoslovak legal order. Therefore all the normative acts of the Interim Czechoslovak Government, including the Decree No. 108/1945 Coll. - also as a consequence of their ratihabition by the Interim National Assembly - are the manifestation of the legal Czechoslovak (Czech) legislature and constitute the culmination of efforts of the Czechoslovak nations to restore the Constitutional and legal order of the Republic.—Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic, Case No. II. ÚS 45/94, published as No. 5/1995 Coll.[17]

- Beneš' right to issue the decrees, despite the existence of a formal protectorate government and German occupation:

The Czechoslovak legal order was based on the Act No. 11/1918 Coll. of 28 November 1918, on the Establishment of the Independent Czechoslovak State. This basis of the Czechoslovak law could not be in any way challenged by the German occupation, not only because the Articles 42 through 56 of the Convention respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land clearly demarcated the borders within which the occupant could have exercised the state powers within the territory of the occupied state, but especially because the German Empire, being a totalitarian state lead by the Rosenberg's principle: Recht ist, was dem Volke nützt ("Whatever serves the German nation is the law"), was performing the state power and enacting legal order essentially notwithstanding its material value. (...) In the contradiction to this, the Constitutional requirement of the democratic character of the Czechoslovak state as defined in the 1920 Constitution may be a concept of political science (and only hardly defined in legal terms), however, that does not mean that it is metajuridical and that it is not legally binding. To the contrary, being the basic characteristic of the constitutional order, it has the effect that the constitutional principle of democratic legitimacy of the state order took precedence over the requirement of formal legal legitimacy in the 1920 Constitution.—Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic, Case No. II. ÚS 45/94, published as No. 5/1995 Coll.[18]

- Decrees appropriate for the time of their issuance, in accordance with international consensus:

The general belief, as it was formed during the second world war and shortly afterwards, included the conviction regarding the necessity of recourse of the Nazi regime and restoration, or at least redress, of damages perpetrated by this regime and by the war. Taking this into consideration, the Decree No. 108/1945 Coll. does not contradict the "legal principles of civilized societies in Europe held valid in this century", but it is a legal act appropriate to its time, supported by the international consensus.—Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic, Case No. II. ÚS 45/94, published as No. 5/1995 Coll.[19]

- Decrees using the principle of responsibility, rather than guilt:

It must be stressed, that even as regards persons of German nationality, there was no presumption of "guilt", but a presumption of "responsibility". The category of "responsibility" aims clearly beyond the boundaries of "guilt" and therefore it has much larger, value-wise, social, historical as well as legal extent. (...) Here the question must be raised, whether only the figureheads of the Nazi regime or also those who had profited, fulfilled their orders and did not resist them, are responsible for the gas chambers, concentration camps, mass exterminations, humiliation and de-humanization of millions. (...) Together with the other European states and their governments, unable and unwilling to counter Nazi expansion from the very start, also the German nation is in the first line responsible for the inception and development of Nazism, although there were many Germans who had actively and bravely apposed it.—Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic , Case No. II. ÚS 45/94, published as No. 5/1995 Coll.[20]

- Decrees targeting those hostile to the republic, not an ethnic group in general:

The defining character in definition of the entities whose property was to be confiscated was their hostility to the Czechoslovak Republic and to the Czech and Slovak nations. The hostility presumption is irrebuttable in case of entities in the Art.1(1), i.e. Germany, Hungary, German Nazi Party (...), while it is rebuttable under Art.1(2) in case of physical persons of German or Hungarian ethnicity, i.e. that their property is not subject to confiscation where they prove that they remained loyal to the Czechoslovak Republic, they never committed an offense against the Czech and Slovak nation, and that they had either actively participated in its liberation or were subjected to Nazist or fascist terror. At the same time, according to Art.1(3) the property of physical and legal persons who acted against the sovereignty, independence, democratic and republican legal order, safety and defense of the Czechoslovak Republic (...), notwithstanding ethnicity, was also subject to confiscation.—Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic, Case No. II. ÚS 45/94, published as No. 5/1995 Coll.[21]

- Decrees meeting the proportionality test:

After the Nazi occupation ended, the rights of the former citizens of Czechoslovakia had to be curtailed not because they had different opinions, but because these opinions were in the general context alien to the very essence of democracy and its order of values and because their consequence was a support to a war of aggression. In the case at hand, this curtailment was valid for all cases fulfilling the given premise, i.e. hostile stance to the Czechoslovak Republic and to its democratic state order, notwithstanding ethnicity.—Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic, Case No. II. ÚS 45/94, published as No. 5/1995 Coll.[22]

In Decision 14/1995 Coll. the court held that the decree at issue was legitimate. It found that since the decree has fullfiled its purpose and has not produced legal effects for more than four decades, it may not be reviewed by the court for its adherence to the 1992 Czech constitution. In the court's view, such a review would lack legal purpose and cast doubt on the principle of legal certainty (an essential principle of democracies adhering to the rule of law).[23]

Confiscation formalities

Although under Decrees 12 and 108 confiscations were automatic on the basis of the decrees themselves,[24] Decree 100 (nationalization of large enterprises) required a formal decision by the Minister of Industry. According to the Constitutional Court, if a Decree 100 nationalization decision was made by someone other than the minister the nationalization was invalid and subject to legal challenge.[25]

Abuses

While hearing appeals of court decisions dealing with Decree 12 confiscations, the Constitutional Court held that courts must decide whether a confiscation decision was motivated by persecution and a decree used as a pretext. This applied to cases of those who remained in the Sudetenland after the Munich Agreement (gaining German citizenship while remaining loyal to Czechoslovakia)[24] and those convicted as traitors whose convictions were later overturned (with their property confiscated in the meantime).[26]

Slovakia

Legal status

Slovakia, as a legal successor of Czechoslovakia, adopted its legal order by Article 152 of the Slovak constitution. This includes the Beneš decrees and Czechoslovak Constitutional Act 23/1991 (the Charter of Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms). This act made all acts or regulations not compliant with the charter inoperable. Although the Beneš decrees are a valid historical part of Slovak law, they can no longer create legal relationships and have been ineffective since December 31, 1991.

On September 20, 2007, the Slovak parliament adopted a resolution concerning the untouchability of postwar documents relating to conditions in Slovakia after World War II. The resolution was originally proposed by the ultra-nationalist[27][28][29] Slovak National Party in response to the activities of Hungarian members of parliament and organizations in Hungary.[30] The Beneš decrees were a significant talking point of the Hungarian extremist groups Magyar Garda and Nemzeti Őrsereg, which became active in August 2007. The approved text differed from the proposal in several important respects. The resolution commemorated the victims of World War II, refused the principle of collective guilt, expressed a desire to stop the reopening of topics related to World War II in the context of European integration and declared a wish to build good relationships with Slovakia's neighbors. It also rejected all attempts at revision and questioning of laws, decrees, agreements or other postwar decisions of Slovak and Czechoslovak bodies which could lead to changes in the postwar order, declaring that postwar decisions are not the basis of current discrimination and cannot establish legal relationships.[31] The resolution was adopted by an absolute parliamentary majority and approved by the coalition government and opposition parties, except for the Party of the Hungarian Coalition.[32] It prompted a strong negative reaction in Hungary, and Hungarian President László Sólyom said that it would strain Hungarian-Slovak relations.[33]

Differences from the Czech Republic

Politicians and journalists have frequently ignored differences in conditions between Slovakia and the Czech Republic during the postwar era.[34] In Slovakia, some measures incorrectly called "Beneš decrees" were not presidential decrees but ordinances by the Slovak National Council (SNR). The confiscation of the agricultural property of Germans, Hungarians, traitors and enemies of the Slovak nation was not enforced by the Beneš decrees, but by the Ordinance of the SNR 104/1945; punishment of fascist criminals, occupiers, traitors and collaborators was based on the Ordinance of the SNR 33/1945. The Beneš decrees and SNR ordinances sometimes contained different solutions.

The list of decrees which have never been valid in Slovakia contains several with a significant impact on German and Hungarian minorities in the Czech lands:[35]

| Act number | Name |

|---|---|

| 5/1945 | Presidential decree concerning the invalidity of some transactions involving property rights from the time of loss of freedom and concerning the nationalization of property of Germans, Hungarians, traitors, collaborators and certain organizations and associations |

| 12/1945 | Presidential decree concerning the confiscation and expedited allotment of agricultural property of Germans, Hungarians, traitors and enemies of the Czech and Slovak nations |

| 16/1945 | Presidential decree concerning the punishment of Nazi criminals, traitors and their helpers and extraordinary people's courts |

| 28/1945 | Presidential decree concerning the settlement of Czech, Slovak or other Slavic farmers on the agricultural land of Germans, Hungarians and other enemies of the state |

| 71/1945 | Presidential decree concerning the work duty of persons who have lost Czechoslovak citizenship |

Apologies for postwar persecution

In 1990 the speakers of the Slovak and Hungarian parliaments, František Mikloško and György Szabad, agreed on the reassessment of their common relationship by a commission of Slovak and Hungarian historians. Although the initiative was hoped to lead to a common memorandum about the limitation of mutual injustices, it did not have the expected result.[36] On February 12, 1991 the Slovak National Council formally apologized for postwar persecution of innocent Germans, rejecting the principle of collective guilt.[37] In 2003, speaker of the Slovak parliament Pavol Hrušovský said that Slovakia was ready to apologize for postwar injustices if Hungary would do likewise. Although Hungarian National Assembly Speaker Katalin Szili approved his initiative, further steps were not taken.[38] In 2005 Mikloško apologized for injustices on his own,[39] and similar unofficial apologies were made by representatives of both sides.

Contemporary political effects

According to Radio Prague, since the decrees which dealt with the status and property of Germans, Hungarians and traitors have not been repealed they still affect political relations between the Czech Republic and Slovakia and Austria, Germany and Hungary.[40] Expellees in the Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft (part of the Federation of Expellees) and associated political groups call for the abolition of the Beneš decrees based on the principle of collective guilt.

On 28 December 1989 future Czechoslovak president Václav Havel, at that time a candidate, suggested that former inhabitants of the Sudetenland might apply for Czech nationality to reclaim their lost property. The governments of Germany and the Czech Republic signed a declaration of mutual apology for wartime misdeeds in 1997.

During the early 2000s, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Austrian Chancellor Wolfgang Schüssel and Bavarian Premier Edmund Stoiber demanded that the Beneš decrees be repealed as a precondition for both countries' entrance to the European Union. Hungarian Prime Minister Péter Medgyessy eventually decided not to press the issue.[41]

In 2003 Liechtenstein, supported by Norway and Iceland, blocked an agreement about extending the European Economic Area because of the Beneš decrees and property disputes with the Czech Republic and (to a lesser extent) Slovakia. However, since the two countries were expected to become members of the European Union the issue was moot. Liechtenstein did not recognize Slovakia until 9 December 2009.[42]

Czech President Miloš Zeman said that the Czechs would not consider repealing the decrees because of an underlying fear that doing so would open the door to demands for restitution. According to Time, former Czech foreign minister Jan Kavan said: "Why should we single out the Beneš Decrees? ... They belong to the past and should stay in the past. Many current members of the E.U. had similar laws."[43] In 2009 eurosceptic Czech president Václav Klaus demanded an opt-out of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, feeling that the charter would render the Beneš decrees illegal.[44] In January 2013 conservative Czech presidential candidate Karel Schwarzenberg said, "What we committed in 1945 would today be considered a grave violation of human rights, and the Czechoslovak government, along with President Beneš, would have found themselves in The Hague."[45]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Zimek, Josef (1996), Ústavní vývoj českého státu (1 ed.), Brno: Masarykova Univerzita, pp. 62–105

- ↑ Those who elected German or Hungarian ethnicity and those who became members of German or Hungarian national associations or political parties were considered Germans and Hungarians.

- ↑ Preece, Jennifer Jackson (1998). "Ethnic Cleansing as an Instrument of Nation-State Creation: Changing State Practices and Evolving Legal Norms". Human Rights Quarterly 20: 817–842. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0039.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Thum, Gregor (2006–2007). "Ethnic Cleansing in Eastern Europe after 1945". Contemporary European History 19 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1017/S0960777309990257.

- ↑ Ther, Philipp; Siljak, Ana (2001). Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944-1948. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 201ff. ISBN 0742510948.

- ↑ Glassheim, Eagle (2000). "National Mythologies and Ethnic Cleansing: The Expulsion of Czechoslovak Germans in 1945". Central European History 33 (4): 463–486. doi:10.1163/156916100746428.

- ↑ de Zayas, Alfred-Maurice (1994). A Terrible Revenge: The Ethnic Cleansing of the East European Germans. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994, ISBN 1-4039-7308-3; second revised edition, Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2006.

- ↑ Waters, Timothy William (2006–2007). "Remembering Sudetenland: On the Legal Construction of Ethnic Cleansing". Virginia Journal of International Law 47 (1): 63–148.

- ↑ Phillips, Ann L. (2000), Power and Influence After the Cold War:Germany in the East-Central Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 84

- ↑ Jakoub, Kyloušek (2005), "Sudetoněmecká strana ve volbách 1935 – pochopení menšinového postavení Sudetských Němců v rámci stranického spektra meziválečného Československa [Sudeten German party in 1935 election - understanding of minority position of Sudeten Germans within the party spectrum of the interwar Czechoslovakia]", Rexter (01)

- ↑ Government of Czechoslovakia (1948), Regulation No. 76/1948 Coll., on the returning of the Czechoslovak citizenship to persons of German and Hungarian ethnicity (in Czech), Prague, Section 3

- ↑ Emert, František (2001). Česká republika a dvojí občanství [The Czech Republic and dual citizenship]. C.H.Beck. p. 41. ISBN 9788074003837.

- ↑ "Udělení státního občanství České republiky - Ministerstvo vnitra České republiky". Mvcr.cz. 2011-04-26. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "University of Minnesota Human Rights Library". .umn.edu. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Dagmar Brokova v. The Czech Republic, Communication No. 774/1997 University of Minnesota Human Rights Library

- ↑ "HUDOC Search Page". Hudoc.echr.coe.int. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Všechny tyto úvahy a skutečnosti vedly proto Ústavní soud k závěru, že na Prozatímní státní zřízení Československé republiky, ustavené ve Velké Británii, je nutno nahlížet jako na mezinárodně uznávaný legitimní ústavní orgán československého státu, na jehož území okupovaném říšskou brannou mocí byl nepřítelem znemožněn výkon svrchované státní moci československé, pramenící z ústavní listiny ČSR, uvozené ústavním zákonem č. 121/1920 Sb., jakož i z celého právního řádu československého. V důsledku toho všechny normativní akty prozatímního státního zřízení ČSR, tedy i dekret prezidenta republiky č. 108/1945 Sb. - také v důsledku jejich ratihabice Prozatímním Národním shromážděním (ústavní zákon ze dne 28. 3. 1946 č. 57/1946 Sb.) - jsou výrazem legální československé (české) zákonodárné moci a bylo jimi dovršeno úsilí národů Československa za obnovu ústavního a právního řádu republiky. Case No. II. ÚS 45/94, published as No. 5/1995 Coll.

- ↑ Prvou ze základních otázek v projednávané věci je otázka, zda napadený dekret, totiž dekret prezidenta republiky ze dne 25. 10. 1945 č. 108/1945 Sb. byl vydán v mezích legitimně stanovených kompetencí či naopak, jak tvrdí navrhovatel, stalo se tak v rozporu se základními zásadami právního státu, neboť k jeho vydání došlo orgánem moci výkonné v rozporu s tehdy platným ústavním právem. V této souvislosti je třeba konstatovat, že základem, na němž spočíval právní řád Československé republiky, byl zákon ze dne 28. 10. 1918 č. 11/1918 Sb. z. a n., o zřízení samostatného státu československého. Tento základ československého práva nemohl být v žádném směru zpochybněn německou okupací, nejen z toho důvodu, že předpisy článků 42 až 56 Řádu zákonů a obyčejů pozemní války představující přílohu IV. Haagské úmluvy ze dne 18. 10. 1907 vymezily přesné hranice, v nichž okupant mohl uplatňovat státní moc na území obsazeného státu, ale především proto, že Německá říše jako totalitní stát, řídící se principem vyjádřeným Rosenbergovou větou - Právem je to, co slouží německé cti - vykonávala státní moc a vytvářela právní řád v zásadě již stranou jejich materiálně hodnotové báze. Tuto skutečnost snad nejlépe vystihují dva říšské zákony z roku 1935, totiž zákon o ochraně německé krve a cti a zákon o říšském občanství, v nichž se klade eminentní důraz na čistotu německé krve, jako předpokladu další existence německého lidu, a v nichž se jako říšský občan definuje pouze státní příslušník z německé nebo příbuzné krve, který dokazuje svým chováním, že je ochoten a schopen věrně sloužit německému národu a říši. Naproti tomu ústavní požadavek demokratické povahy československého státu v ústavní listině z roku 1920 formuluje sice pojem politicko-vědní povahy (jenž je juristicky obtížně definovatelný), což však neznamená, že je metajuristický a že nemá právní závaznost. Naopak, jako základní charakteristický rys ústavního zřízení znamená ve svých důsledcích, že nad a před požadavek formálně-právní legitimity byl v ústavní listině Československé republiky z roku 1920 postaven ústavní princip demokratické legitimity státního zřízení. Case No. II. ÚS 45/94, published as No. 5/1995 Coll.

- ↑ V hodnotovém nazírání, jak se vytvářelo během druhé světové války a krátce po ní, bylo naopak obsaženo přesvědčení o nezbytnosti postihu nacistického režimu a náhrady, či alespoň zmírnění škod způsobených tímto režimem a válečnými událostmi. Ani v tomto směru tedy dekret prezidenta republiky č. 108/1945 Sb. neodporuje "právním zásadám civilizovaných společností Evropy platným v tomto století", ale je právním aktem své doby opírajícím se i o mezinárodní konsens. Case No. II. ÚS 45/94, published as No. 5/1995 Coll.