Bembine Tablet

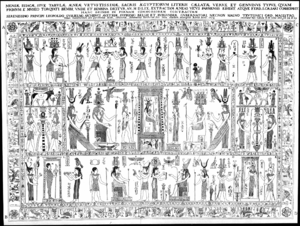

The Bembine Tablet, the Bembine Table of Isis or the Mensa Isiaca (Isiac Tablet) is an elaborate tablet of bronze with enamel and silver inlay of probable Roman origin and mimicking Egyptian style. It was used by the 17th century hermeticist Athanasius Kircher as the primary source for developing his translations of Egyptian hieroglyphics; the hieroglyphics on the Tablet are now known to be nonsense, and Kircher's translations spurious.[1][2] It was also celebrated by later occultists including Eliphas Levi, William Wynn Westcott and Manly P. Hall as a key to interpreting the "Book of Thoth" or Tarot, and Thomas Taylor even claimed that this tablet formed the altar before which Plato stood as he received initiation within a subterranean hall in the Great Pyramid of Giza. The Tablet was named after Cardinal Bembo, a celebrated antiquarian who acquired it after the 1527 sack of Rome.[2]

Origins

The Tablet has been dated to some time in the first century, probably originating in Rome.[1] Nothing is known of it until after the sack of Rome. Cardinal Bembo acquired it at an exorbitant price from a certain locksmith or ironworker into whose hands it had fallen. After Bembo's death in 1547 the Tablet was acquired by the House of Mantua, remaining in their museum until the capture of Mantua in 1630 by Ferdinand II's troops. The Tablet eventually came into the hands of Cardinal Pava, who presented it to the Duke of Savoy, who in turn presented it to the King of Sardinia. With the French conquest of Italy in 1797 the Tablet came to Paris, and Alexandre Lenoir wrote in 1809 that it was on exhibition in the Bibliothèque Nationale. It was later returned to Italy after peace was established. Karl Baedeker in his Guide to Northern Italy mentions that the tablet was a central exhibit in Gallery 2 in the Museum of Antiquities at Turin, where it is today.[2][3]

Construction

Kircher describes the Tablet as "five palms long and four wide", while Westcott measures it at 50×30 inches.[2] It was made of bronze with enamel and silver inlay, the figures cut very shallow and the contours of most of them delineated with thin silver wire. The bases on which the figures sat were covered with silver, which had been torn away, and these sections are left blank in the engraved reproduction.[4]

The Tablet is an important example of ancient metallurgy, its surface being decorated with a variety of metals including silver, gold, copper-gold alloy and various base metals. One of the metals employed is black, made by alloying copper and tin with small amounts of gold and silver, and then 'pickling' it in organic acid. This black metal is possibly a variety of the "Corinthian bronze" described by Pliny and Plutarch.[1]

Depicted scene

Although the scenes are Egyptianising, they do not depict Egyptian rites. Figures are shown with non-customary attributes, making it unclear which are divinities and which kings or queens. Egyptian motifs are used without rhyme or reason. However the central figure is recognisable as Isis, suggesting that the Tablet originates in some centre of her worship, possibly even the Iseum Campensis.[1]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Museum of Antiquities, Turin. Retrieved 13 December 2006

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Hall, Manly Palmer (1928). The Secret Teachings of All Ages.

- ↑ William Bates, The Brazen Table of Bembo & Hieroglyphics

- ↑ Thomas Dudley Fosbroke, Encyclopædia of Antiquities