Bell state

The Bell states are a concept in quantum information science and represent the most simple examples of entanglement. They are named after John S. Bell because they are the subject of his famous Bell inequality. An EPR pair is a pair of qubits which are in a Bell state together, that is, entangled with each other. Unlike classical phenomena such as the nuclear, electromagnetic, and gravitational fields, entanglement is invariant under distance of separation and is not subject to relativistic limitations such as the speed of light (though the no-communication theorem prevents this behaviour being used to transmit information faster than light, which would violate causality).

The Bell states

Bell states are specific maximally entangled quantum states of two qubits.

The degree to which a state is entangled is monotonically measured by the Von Neumann entropy of the reduced density operator of a state. The Von Neumann entropy of a pure state is zero - also for the bell states which are specific pure states. But the Von Neumann entropy of the reduced density operator of the Bell states is maximal[1]

The qubits are usually thought to be spatially separated. Nevertheless they exhibit perfect correlation which cannot be explained without quantum mechanics.

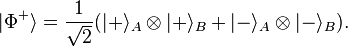

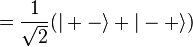

In order to explain this, it is important to first look at the Bell state  :

:

This expression means the following: The qubit held by Alice (subscript "A") can be 0 as well as 1. If Alice measured her qubit in the standard basis the outcome would be perfectly random, either possibility having probability 1/2. But if Bob then measured his qubit, the outcome would be the same as the one Alice got. So, if Bob measured, he would also get a random outcome on first sight, but if Alice and Bob communicated they would find out that, although the outcomes seemed random, they are correlated.

So far, this is nothing special: maybe the two particles "agreed" in advance, when the pair was created (before the qubits were separated), which outcome they would show in case of a measurement.

Hence, followed Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen in 1935 in their famous "EPR paper", there is something missing in the description of the qubit pair given above—namely this "agreement", called more formally a hidden variable.

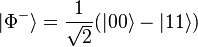

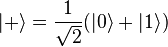

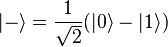

But quantum mechanics allows qubits to be in quantum superposition—i.e. in 0 and 1 simultaneously—that is, a linear combination of the two classical states—for example, the states  or

or  . If Alice and Bob chose to measure in this basis, i.e. check whether their qubit were

. If Alice and Bob chose to measure in this basis, i.e. check whether their qubit were  or

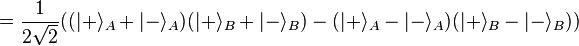

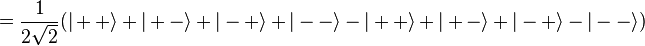

or  , they would find the same correlations as above. That is because the Bell state can be formally rewritten as follows:

, they would find the same correlations as above. That is because the Bell state can be formally rewritten as follows:

Note that this is still the same state.

John S. Bell showed in his famous paper of 1964 by using simple probability theory arguments that these correlations cannot be perfect in case of "pre-agreement" stored in some hidden variables—but that quantum mechanics predict perfect correlations. In a more formal and refined formulation known as the Bell-CHSH inequality, this would be stated such that a certain correlation measure cannot exceed the value 2 according to reasoning assuming local "hidden variable" theory (sort of common-sense) physics, but quantum mechanics predicts  .

.

There are three specific other states of two qubits which are also regarded as Bell states and which lead to this maximal value of  . The four are known as the four maximally entangled two-qubit Bell states:

. The four are known as the four maximally entangled two-qubit Bell states:

Bell state measurement

The Bell measurement is an important concept in quantum information science: It is a joint quantum-mechanical measurement of two qubits that determines which of the four Bell states the two qubits are in.

If the qubits were not in a Bell state before, they get projected into a Bell state (according to the projection rule of quantum measurements), and as Bell states are entangled, a Bell measurement is an entangling operation.

Bell-state measurement is the crucial step in quantum teleportation. The result of a Bell-state measurement is used by one's co-conspirator to reconstruct the original state of a teleported particle from half of an entangled pair (the "quantum channel") that was previously shared between the two ends.

Experiments which utilize so-called "linear evolution, local measurement" techniques cannot realize a complete Bell state measurement. Linear evolution means that the detection apparatus acts on each particle independently from the state or evolution of the other, and local measurement means that each particle is localized at a particular detector registering a "click" to indicate that a particle has been detected. Such devices can be constructed, for example, from mirrors, beam splitters, and wave plates, and are attractive from an experimental perspective because they are easy to use and have a high measurement cross-section.

For entanglement in a single qubit variable, only three distinct classes out of four Bell states are distinguishable using such linear optical techniques. This means two Bell states cannot be distinguished from each other, limiting the efficiency of quantum communication protocols such as teleportation. If a Bell state is measured from this ambiguous class, the teleportation event fails.

Entangling particles in multiple qubit variables, such as (for photonic systems) polarization and a two-element subset of orbital angular momentum states, allows the experimenter to trace over one variable and achieve a complete Bell state measurement in the other.[2] Leveraging so-called hyper-entangled systems thus has an advantage for teleportation. It also has advantages for other protocols such as superdense coding, in which hyper-entanglement increases the channel capacity.

In general, for hyper-entanglement in  variables, one can distinguish between at most

variables, one can distinguish between at most  classes out of

classes out of  Bell states using linear optical techniques.[3]

Bell states using linear optical techniques.[3]

Bell state correlations

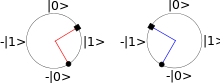

Independent measurements made on two qubits that are entangled in Bell states positively correlate perfectly if each qubit is measured in the relevant basis. For the  state, this means selecting the same basis for both qubits. If an experimenter chose to measure both qubits in a

state, this means selecting the same basis for both qubits. If an experimenter chose to measure both qubits in a  Bell state using the same basis, the qubits would appear positively correlated when measuring in the

Bell state using the same basis, the qubits would appear positively correlated when measuring in the  basis, anti-correlated in the

basis, anti-correlated in the  basis[lower-alpha 1] and partially (probabilistically) correlated in other bases.

basis[lower-alpha 1] and partially (probabilistically) correlated in other bases.

The  correlations can be understood by measuring both qubits in the same basis and observing perfectly anti-correlated results. More generally,

correlations can be understood by measuring both qubits in the same basis and observing perfectly anti-correlated results. More generally,  can be understood by measuring the first qubit in basis

can be understood by measuring the first qubit in basis  , the second qubit in basis

, the second qubit in basis  and observing perfectly positively-correlated results.

and observing perfectly positively-correlated results.

state.

state.| Bell state | Basis  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

See also

References

- ↑ Quantum Entanglement in Electron Optics: Generation, Characterization, and Applications, Naresh Chandra, Rama Ghosh, Springer, 2013, ISBN 3642240704, p. 43, Google Books

- ↑ Kwiat, Weinfurter. "Embedded Bell State Analysis"

- ↑ Pisenti, Gaebler, Lynn. "Distinguishability of Hyper-Entangled Bell States by Linear Evolution and Local Measurement"

- Nielsen, Michael A.; Chuang, Isaac L. (2000), Quantum computation and quantum information, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-63503-5, pp. 25.

- Kaye, Phillip; Laflamme, Raymond; Mosca, Michele (2007), An introduction to quantum computing, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-857049-3, pp. 75.

- On the Einstein Podolsky and Rosen paradox, Bell System Technical Journal, 1964.