Belgrade Offensive

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

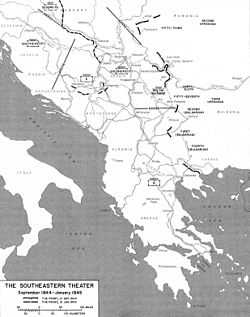

The Belgrade Offensive or the Belgrade Strategic Offensive Operation (Serbo-Croatian: Beogradska operacija, Београдска операција; Russian: Белградская стратегическая наступательная операция, Belgradskaya strategicheskaya nastupatel'naya operatsiya) (14 September - 24 November 1944)[4] was an offensive military operation in which Belgrade was liberated from the German Wehrmacht by the joint efforts of the Soviet Red Army, the Yugoslav Partisans, and the Bulgarian People's Army. These forces launched separate but loosely coordinated operations that successfully forced the Germans out of the Belgrade area.[5] The Red Army advance across Yugoslav borders followed after an agreement between Tito's provisional government and Stalin in Moscow in September 1944. This agreement envisaged an immediate withdrawal of Soviet troops from Yugoslav territory after the conclusion of the operations.[6] Bulgarian troops were put under the control of the 3rd Ukrainian Front Command, while "combat cooperation between the Red Army and the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia was accomplished by accepting unique concept of operations and by coordination of the supreme headquarters of both armies", and later "by personal contacts commanders and staffs".[7] Bulgarian units were allowed to participate in battles on Yugoslav soil due to the agreement between Marshal Tito and Bulgarian representative Dobri Terpesev on 5 October, but Yugoslav-Bulgarian cooperation did not proceed without difficulties and mutual accusations.[8]

The offensive was executed by elements of the Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front and Yugoslav 1st Army Group and XIV Army Corps. Related activities to the south included the Bulgarian 2nd Army and Yugoslav XIII Army Corps, as well as the advancement of the 2nd Ukrainian Front elements northwards from the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border, contributed to the success of the offensive.[9] The First, Third and elements of the Fourth Bulgarian armies and XV, XVI and Bregalnica corps of NOVJ attacked Army Group E forces in Macedonia.[10][11]

German forces in Serbia were combined from parts of different formations, urgently brought from the 2nd Panzer Army and Army Group E, and put under the joint command of General Felber's headquarters under the provisional name of "Army Group (or: Army Detachment) Serbia", under the higher command of Army Group F.[12]

The objective of the offensive was to destroy the German forces in eastern and central Serbia, to seize Belgrade as a major strategic point in the Balkans, and to break the main German communication line between Greece and Hungary.[13]

Background

Developments in Yugoslavia

By the summer of 1944, the Germans had not only lost control of practically all the mountainous area of Jugoslavia, but were no longer able to protect their own essential lines of communication. Another general offensive on their front was unthinkable; and by September it was clear that Belgrade and the whole of Serbia must shortly be free of them. These summer months were the best the movement had ever seen; there were more recruits than could be armed or trained, desertions from the enemy reached high numbers; one by one the objectives of resistance were reached and taken.[14]

In August 1943, the German Wehrmacht had two army formations deployed in the Balkans: Army Group E in Greece and the 2nd Panzer Army in Yugoslavia and Albania. Army Group F headquarters (Generalfeldmarschall von Weichs) in Belgrade acted as a joint higher command for these formations, as well as for Bulgarian and Quisling formations.

After the collapse of the uprising in December 1941, anti-Axis activity in Serbia decreased significantly, and the focus was moved to other areas. Consequently, although Serbia had great significance to the Germans, very few troops actually remained in Serbia (according to Schmider only about 10,000 in June 1944[15]). In the following years, Tito repeatedly tried to reinforce the partisan forces in Serbia with experienced units from Bosnia and Montenegro. From the spring of 1944, the Allied command had assisted in these efforts.[16] The Germans actively opposed these efforts by concentrating forces in the border regions of Bosnia and Montenegro, in order to disturb Partisan concentrations, to inflict casualties on Partisan units and to push them back with a series of large-scale assaults.

In July 1944, German defenses began to fail. After the failure of Operation Draufgänger (Daredevil) - a 1944 anti-partisan operation in Montenegro, Yugoslavia, and Northern Albania - three divisions of the Narodnooslobodilačka vojska Jugoslavije (the People's Liberation Army of Yugoslavia) (NOVJ) - managed to cross the Ibar River to the east and threaten the main railroad lines. After the failure of Operation Rübezahl in Montenegro (August 1944), two additional NOVJ divisions broke through the German blockade, successfully entrenching themselves in western Serbia. Army Group F command responded by deploying additional forces: the 1st Mountain Division arrived in Serbia in early August, followed by the 4th SS Panzergrenadier Division from the Thessaloniki area.

Developments in Romania in late August 1944 confronted Army Group F command with the necessity of an immediate large-scale concentration of troops and weapons in Serbia in order to cope with a threat from the east. The Allied command and the NOVJ supreme command predicted this scenario and developed a plan for the occasion: on 1 September 1944, there began a general attack from the ground and from the air on the German transport lines and installations (Operation Ratweek).[17] These attacks largely hindered German troop movements, with units disassembled and tied to the ground.[18]

In the meantime the 1st Proletarian Corps, the main partisan formation in Serbia, continued with reinforcing and developing its forces and with seizing positions for the assault on Belgrade: on 18 September Valjevo was taken, and on 20 September Aranđelovac. Partisans achieved control of a large area south and southwest of Belgrade, thus forming the basis for the future advance towards Belgrade.

In response to the defeat of German forces in the Jassy-Kishinev Operation in late August 1944 (which forced Bulgaria and Romania to switch sides) and to the advance of Red Army troops into the Balkans, Berlin ordered Army Group E to withdraw into Hungary, but the combined actions of Yugoslav partisans and Allied air forces impeded German movements with Ratweek. With the Red Army on Serbia's borders, the Wehrmacht put together another provisional army formation from available elements of Army Group E and the 2nd Panzer Army for the defense of Serbia, called "Army Group Serbia" (German: Armeeabteilung Serbien).

Regional developments

As a result of the Bulgarian coup d'état of 1944, the monarchist-fascist regime in Bulgaria was overthrown and replaced with a government of the Fatherland Front led by Kimon Georgiev. Once the new government came to power, Bulgaria declared war on Germany. Under the new pro-Soviet government, four Bulgarian armies, 455,000 strong were mobilized and reorganized. In the early October 1944, three Bulgarian armies, consisting of around 340,000 man,[10] were located on the Yugoslav – Bulgarian border.[19][20]

By the end of September, the Red Army 3rd Ukrainian Front troops under the command of Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin were concentrated at the Bulgarian-Yugoslav border. The Soviet 57th Army was stationed in the Vidin area, while the Bulgarian 2nd Army[21] (General Kiril Stanchev commanding under the operational command of the 3rd Ukrainian Front) was stationed to the south on the Niš rail line at the junction of Bulgarian, Yugoslav, and Greek borders. This further caused the arrival of the Partisans 1st Army from Yugoslav territory, in order to provide support to their 13th and 14th Corps collaborating in the liberation of Niš and supporting the 57th Army’s advance to Belgrade, respectively. The Red Army 2nd Ukrainian Front’s 46th Army was deployed in the area of the Teregova river (Romania), poised to cut the rail link between Belgrade and Hungary to the north of Vršac.

Pre-operations were coordinated between the Soviets and the commander-in-chief of the Yugoslav Partisans, Marshal Josip Broz Tito. Tito arrived in Soviet-controlled Romania on 21 September, and from there flew to Moscow where he met with Soviet premier Joseph Stalin. The meeting was a success, in particular because the two allies reached an agreement concerning the participation of Bulgarian troops in the operation that would be conducted on Yugoslav territory.

The offensive

Before the start of ground operations the Soviet 17th Air Army (3rd Ukrainian Front) was ordered to impede the withdrawal of German troops from Greece and southern regions of Yugoslavia. To do so, from, it carried out air attacks on the railroad bridges and other important facilities in the areas of Niš, Skopje, and Kruševo lasting from 15–21 September.

Plan of the offensive

It was necessary for the Yugoslavs to break through German defensive position on the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border to gain control of roads and mountain passages through eastern Serbia, to penetrate into the valley of the Great Morava river, and to secure the bridgehead on the western bank. This task was to be executed mainly with the 57th Army, and Yugoslav XIV Army Corps was ordered to co-operate and support the Red Army attack behind the front line.[22]

After the successful completion of the first stage it was planned to deploy 4th Guards Mechanized Corps to the bridgehead on the west bank. This Corps with its tanks, heavy weapons and impressive firepower was compatible with Yugoslav 1st Army Group, which had significant manpower concentrated, but armed mainly with light infantry weapons. These two formations joined were ordered to execute the main attack on Belgrade from the south.[23] Advantages of this plan were possibility of rapid development of forces in the critical final stage of the offensive, and possibility of cutting off German forces in eastern Serbia from their main forces.

First Stage

Local situation

Partisan operational units in January 1944 left the northern part of east Serbia under the pressure of occupiers and auxiliary forces. In the area remained Bulgarian garrisons, some German police forces and Serbian Quisling troops, all under the German command, and Chetniks, mostly covered with agreements with Germans. Partisan forces (23rd and 25th Division) returned to the central parts of east Serbia in July and August 1944, forming a free territory with makeshift runway in Soko Banja, securing thus air supply with arms and ammunition, and evacuation of the wounded. After the coup in Romania, the importance of northern part of east Serbia had risen for both sides. In a race against each other, Partisans, as better positioned, were faster. 23rd Division in fierce battle with German police battailons and auxiliary forces, took Zaječar on 7 September, and on 12 September entered Negotin, with 25th Division unsuccessfully attacking Donji Milanovac at the same time. Volunteers were coming in into the units in large numbers, so the units increased in numbers. New, 45th Serbian Division was formed on 3 September, and on 6 September 14 Corps headquarters was established as a higher command for the area of operations.

Germans intervened with 1st Mountain Division, reaching Zaječar on 9 September. Over the next week Partisans led defensive fightings, trying to deny access to the Danube on Negotin to Germans in expecting of the Red Army forces to cross over from Romania. Since this did not happen, 14th Corps on 16 September decided to abandon the defense of the Danube coastline, and to focus on attacking German columns in maneuvering.

On 12 September near Negotin, a NOVJ delegation led by colonel Đurić crossed over the Danube to the Romanian side, and establish a contact with the Red Army 74th Rifle Division. The delegation was accompanied to Romanian territory by the 1st Battalion of the 9th Serbian Brigade; the 1st Battalion would fight within the 109th Regiment of 74th Rifle Division until 7 October.

Army Group F Commander Feldmarschall von Weichs ordered in August 1944 the concentration of his mobile forces in Serbia to combat Partisans. This included 4th SS Police Division, 1st Mountain Division, 92nd Motorized Regiment, 4th Regiment Brandenburg, 191st Brigade of assault guns and 486th armored reconnaissance troop. As a counter-measure to the events in Romania and Bulgaria, he ordered 11th Luftwaffe Field Division, 22nd Infantry, 117th, 104th Jäger Division and 18th SS police regiment to advance to Macedonia.

1st Mountain Division was withdrawn from participation in operations against partisans in Montenegro, to be transported to the Niš area. On 6 September it was placed under the command of General Felber, with the task to establish the control on the Bulgarian border. By mid-September, the division won control of Zaječar and reached the Danube, thus reaching the area where the main attack was expected. 7th SS Division maintained that under the command of the 2nd Panzer Army, attacking the partisan units forwarding to Serbia from eastern Bosnia and Sandžak. Division was subordinated to General Felber on 21 September, with the intention of offensive against the partisans in western Serbia. However, due to the deteriorating situation on the eastern border, this intention was cancelled. Starting with the end of September, the division was transferred to southeast Serbia, taking upon itself the southern part of Serbian front-line, between Zaječar and Vranje. This enabled the 1st Mountain Division to concentrate to the north, in the area between Zaječar and Iron Gates. 1st Mountain Division was strengthened with 92 Motorized Regiment, 2nd Brandenburg and 18th SS Regiment. Both divisions integrated in their composition parts of German units withdrawn from Romania and Bulgaria, and parts of local formations. 1st Mountain Division mounted an attack on the left bank of the Danube in order to gain control of the Iron Gates, but its attack on 22 September failed in collision with the attack of the 75th Corps of the Red Army advancing in the opposite direction.

Attack of the 57th Army

After Iassy-Kishinev Operation, wide and deep area of possible advancement opened up in front of the Red Army. This started a race between Soviets and Germans to the "Blue Line", an intended front-line from the southern slopes of the Carpathians over Iron Gates down the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border. By the end of September, both 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Front managed to deploy some 19 Riffle Divisions with supporting units to the line (in comparison to 91 Riffle Divisions in Iassy-Kishinev Operation).[1] Vast terrain with poor and damaged roads, uncertainty with local forces, dispersed German groups and logistic difficulties slowed the advancement down. On the other side, Army Group F encountered much larger problems in concentrating their forces. This resulted in Red Army achieving substantial superiority in numbers on the Blue Line by the end-September. Given this fact, and the prospects of cooperation with NOVJ in depth of the territory, despite the relatively modest strength gathered in absolute numbers, the offensive was launched.

First to reach the Iron Gates area were reconnaissance elements of the 75th Riffle Corps. On 12 September they established a contact with the partisans on the other side of the Danube. However, in following days, the Germans succeeded to push out partisans from the shore, and to launch a limited attack on Red Army elements across the Danube. According to the general plan, the 75th Corps was to be included in the composition of the 57th Army during its attack south of the Danube, and the completion of the 57th Army transfer to the Vidin area was not expected before 30 September. Having fluid situation on the Yugoslav side of the Iron Gates and a German attack across the Danube, 75th Corps launched its attack earlier, crossing the Danube on 22 September. After initial success, in the next days German 1st Mountain Division undertook a vigorous counter-attack, pushing the Soviets back against the Danube. Because of this, the 57th Army attack was launched with available elements, before the completion, on the night between 27 and 28 September. Divisions of 68th and 64th Riffle Corps were introduced in the area from Negotin to Zaječar.

This attack of three Army Corps created supremacy of the Red Army on the combat line, and despite of the stubborn German defense, Red Army was advancing. On 30 September Negotin was liberated and heavy fighting erupted for Zaječar.

Army Group F Command in Belgrade sought to bring more units to Belgrade as soon as possible. C-in-C von Weichs ordered that 104th Jäger Division should be transported immediately as soon as transport of 117th Jäger Division was completed. However, transport from the south was hindered with partisan operations and Allied Air Force attacks. 117th Jäger Division has been boarded on 44 trains in Athens on 19 September, but only 17 out of 44 reached Belgrade until 8 October. 104th Jäger Division remained blocked in Macedonia. Because of insufficiency of troops at the front-line, Army Group F Command on 29 September qualified defensive effort of 1st Mountain Division and 92nd Motorized Brigade as an attempt to buy time. Assault Regiment Rhodes was transported to Belgrade by air without heavy weapons, but this method of transport could not meet the needs.

The attack of three Soviet Rifle Corps supported by the 14th Corps NOVJ on the German forces stretched between Donji Milanovac and Zaječar gradually progressed, despite persistent resistance. The fight diverged into a number of skirmishes for the strongpoints in towns and on the crossroads and passes, and Germans were forced to gradual withdrawal. 14th Corps NOVJ won the control over communications behind the front-line, and commander of the 57th Army sent his Chief of Staff Major General Verkholovich (Russian: Верхолович) to the 14th Corps HQ to coordinate actions.[24] 223rd Division of the 68th Corps on 1 October after fierce battle seized an important crossroad in the village Rgotina, 10 km to the north of Zaječar. Another important crossroad in Štubik fell on 2 October after a bitter battle. On 3 October parts of 223rd Division and the 7th and 9th Serbian Brigade of the 23rd Division NOVJ liberated Bor, important for its large copper mine. In Bor 7th and 9th Brigade liberated some 1,700 forced laborers, mostly Jews from Hungary.[25]

Due to successful attacks, by 4 October German forces in front of the Soviet 57th Army were separated into three battle groups with no contact with each other: Battle group Groth that held Zaječar was the southernmost, battle group Fisher held positions in the middle, and battle group Stettner (named after 1st Mountain Division commander) held grounds in mountains further to the north. Having firmly in their hands crossroads in the interspaces Soviet command decided to postpone decisive attack on German battle groups, and to exploit the open roads for deeper penetration with mobile forces. 5th Guards Motorized Rifle Brigade, reinforced with self-propelled artillery regiment and anti-tank regiment, headed on 7 October in marching order from Negotin over Rgotina and Žagubica to Svilajnac. In 24 hours the brigade performed a 120 km long march-maneuver, reaching on 8 October Great Morava valley, thus leaving German front forces far behind. On the next day 93rd Riffle Division broke 9 October into the Great Morava valley through Petrovac. Division commander formed the special task force under captain Liskov, for capturing the only 30-ton bridge over the river near village Donje Livadice. Captain Liskov's group successfully neutralized German guards and prevented them from mining the bridge, which had a great importance for the further course of the offensive. On 10 October 93rd Riffle Division and 5th Motorized Brigade secured the bridgehead on the west bank of the Great Morava river.[26]

On 7 October 64th Riffle Corps units together with elements of 45th Division NOVJ finally managed to break the steadfast resistance of battle group Groth and to take Zaječar. At the same time, owing to great efforts of engineer units, 4th Guards Mechanized Corps transports reached the Vidin area. The Corps on 9 October passed through Zaječar in marching order, heading to the bridge over the Great Morava. After crossing the bridge, on 12 October in the area of Natalinci, 12 km east of Topola the Corps met with the 4th Brigade of the 21st Serbian Division NOVJ.[27] 4th Guards Mechanized Corps with its 160 tanks, 21 self-propelled guns, 31 armored cars and 366 guns and mortars,[28] had impressive firepower. Together with Yugoslav 1st Proletarian Corps, concentrated in the area, 4th Guards Mechanized Corps formed the main attack force for the direct assault on Belgrade. With this concentration of forces in the area west of Great Morava, the first phase of the offensive was successfully concluded.

Second stage

German counter-measures

On 2 October, German command structure was reorganized. Energetic General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller, former commander of German forces on Crete, resumed command over the front-line south of Danube. His Corps headquarters was located in Kraljevo. General Schneckenburger retained command of the immediate defense of Belgrade and the forces north of the Danube. Both Corps commands were subordinated to General Felber's Army Detachment Serbia command, under C-in-C South-east (Army Group F) Higher Command.

As Belgrade became an endangered combat zone, Army Group F headquarters was on October 5 relocated from Belgrade to Vukovar. Felber and Schneckenburger remained in Belgrade.

On 10 October Army Group F command acknowledged that the Red Amy had opened a hole in their front line, and had penetrated into the Great Morava valley. These Soviet forces threatened to proceed with a direct attack on Belgrade, and to cut off the 1st Mountain Division, still stuck in combat in east Serbia, and to attack it from the rear. Command stated its determination to close the hole with a counter-attack, but they lacked troops for such an undertaking. With the possibility of reinforcement from the south finally discarded, it was forced to seek more troops from 2nd Panzer Army. Previous deployment of forces for the front-line in Serbia already cost 2nd Panzer Army a number of important towns, some for good (Drvar, Gacko, Prijedor, Jajce, Donji Vakuf, Bugojno, Gornji Vakuf, Tuzla, Hvar, Brač, Pelješac, Berane, Nikšić, Bileća, Trebinje, Benkovac, Livno), and some temporarily (Užice, Tešanj, Teslić, Slavonska Požega, Zvornik, Daruvar, Pakrac, Kolašin, Bijelo Polje, Banja Luka, Pljevlja, Virovitica, Višegrad, and Travnik). A new defensive plan put into operation on 10 October allowed 2nd Panzer Army to abandon most of the Adriatic coast, and to form a new defensive line from the mouth of Zrmanja eastwards, relying on mountain ranges and fortified towns. This defensive line was to be held with three 'legionnaire' divisions (369th, 373rd and 392nd), and it should allow Germans to draw out two divisions (the 118th and the 264th) for use in critical areas. However, due to the failure of the 369th Division, only two battalion-strong battle-groups of the 118th Division were sent to Belgrade, while the 264th was caught in the offensive of the 8th Yugoslav Corps, and was eventually destroyed in the Knin area.

Activities on the flanks

The operations begun on the far southern flank of the Front with the offensive by the 2nd Bulgarian Army into the Leskovac-Niš area, and almost immediately engaged the infamous 7th SS Mountain Division "Prinz Eugen". Two days later, having encountered the Yugoslav partisans, the Army with partisan participation defeated a combined force of Chetniks and Serbian Frontier Guards and occupied Vlasotince. Using its Armored Brigade as a spearhead, the Bulgarian Army then engaged German positions on 8 October at Bela Palanka, reaching Vlasotince two days later. On 12 October, the Armored Brigade—supported by the 15th Brigade of the 47th Partisan Division—was able to take Leskovac, with the Bulgarian reconnaissance battalion crossing the Morava and probing toward Niš. The goal of this was to not so much to pursue the remnants of the "Prinz Eugen" Division withdrawing northwest, but to for the Bulgarian 2nd Army to begin the liberation of Kosovo which would have finally cut the route north for the German Army Group E withdrawing from Greece. On 17 October, the leading units of the Bulgarian Army reached Kursumlija, and proceeded to Kuršumlijska Banja. On 5 November, after negotiating the Prepolac Pass with heavy losses, the Brigade occupied Podujevo, but was unable to reach Pristina until the 21st.[29]

On the northern face of the offensive, the Red Army 2nd Ukrainian Front's supporting 46th Army advanced in the attempt to outflank the German Belgrade defensive position from the north, by cutting the river and rail supply lines running along the Tisa. Supported by the 5th Air Army, its 10th Guards Rifle Corps was able to rapidly perform assault crossings of the rivers Tamiš and Tisa north of Pančevo to threaten the Belgrade-Novi Sad railroad. Further to the north the Red Army 31st Guards Rifle Corps advanced toward Petrovgrad, and the 37th Rifle Corps advanced toward, and assault crossed the Tisa to threaten the stretch of railway between Novi Sad and Subotica to prepare for the planned Budapest strategic offensive operation.[30]

Assault on Belgrade

Approaching Belgrade

On 12 October, of the whole area between Kragujevac and Sava, with the exception of Belgrade, Germans held only solitary strongholds in Šabac, Obrenovac, Topola and Mladenovac, while the interspaces were in control of NOVJ. After the liberation of Valjevo, divisions of 12th Corps and the 6th Division scattered Chetniks, pushed back German elements (battle-group von Jungenfeld) south of Šabac, and entered the area between Belgrade and Obrenovac. Chetnik elements that had retreated to Belgrade, were transported to Kraljevo by the Germans on 3–5 October. 1st and 5th Division held Topola and Mladenovac under pressure, and was reinforced with the 21st Division, which marched in from the south.

On that day, the complete 4th Guards Mechanized Corps was concentrated to the west of Topola. Germans formed two combat groups for the intended attack to throw them back across Great Morava. The attack of the southern combat group from Kragujevac was easily blocked, and with the northern battle group, Corps dealt along its advancement towards Belgrade. The main direction of attack, line Topola-Belgrade, was entrusted to 36th Tank Brigade, 13th and 14th Guards Mechanized Brigade of Red Army, and to 1st, 5th and 21st division NOVJ. The task to penetrate on additional direction, on the right flank, towards the Danube and Smederevo, was given to 15th Guards Mechanized Brigade, reinforced with 5th Independent Mechanized Brigade, two artillery regiments and with 1st Brigade of 5th Division NOVJ.

The final run towards Belgrede started on 12 October. Auxiliary right flank attack of 15th Guards Mechanized Brigade and 1st Brigade of 5th Division NOVJ reached Danube near Boleč late in the evening on 13 October, after a charge through the positions on Brandenburgers.[31] With this success German forces were cut into two separate parts: Belgrade garrison to the west, and the battle-group retreating from eastern Serbia, at the time in the Smederevo area. The latter, consisting of 1st Mountain Division, 2nd regiment Brandenburg and the elements of other units, under general Walter Stettner, was cut off from all other German units, facing the danger of the destruction. Efforts of this group to break through and to establish link with Belgrade garrison, resulted in fierce fighting in the interspace. In the following days, 21st and 23 Division NOVJ were deployed to strengthen positions and to prevent Germans from rejoining.

36th Tank Brigade led attack on the main direction. With the 4th Battalion of the 4th Serbian Brigade boarded on the tanks, 36th headed towards Topola. Parts of the 5th Division NOVJ (10th Krajina Brigade) were holding Topola garrison under attack from the west, when tanks of 36th Tank Brigade suddenly appeared from the east. After short but intense artillery preparation, German garrison was overrun with the joint charge. 36th Tank Brigade continued northwards without delay, and 9 kilometers north of Topola encountered German assault gun battalion marching in opposite direction. After short but fierce clash with serious losses on both sides, 36th Tank Brigade overrun Germans on the move, and proceeded to the north. Before the day of 12 October was over, 36th Tank Brigade also overrun garrison of Mladenovac, the last important obstacle before Belgrade, in the way similar to the action on Topola, with the assistance of 3rd and 4th Krajina Brigade NOVJ.[32] With Mladenovac cleared, the way to Belgrade was wide open.

On the streets of Belgrade

The 4th Guards Mechanized Corps of the Red Army and the Yugoslav 12th Corps broke through the enemy resistance south of Belgrade on 14 October, approaching the city. The Yugoslavs advanced along the roads in the direction of Belgrade south of the Sava River, while the Red Army engaged in fighting on the northern bank outskirts. The assault on the city was delayed due to the diversion of forces for the elimination of thousands of enemy troops surrounded between Belgrade and Smederevo (to the south-east). On 20 October, Belgrade had been completely overrun by joint Soviet and Yugoslav forces.

The Yugoslav 13th Corps, in cooperation with the Bulgarian 2nd Army,[33] advanced from the south-east. They were responsible for the area of Niš and Leskovac. The forces were also responsible for cutting off the main for the evacuation of Army Group E, along the rivers of South Morava and Morava. Army Group E had, therefore, been forced to retreat through the mountains of Montenegro and Bosnia and was unable to strengthen the German forces in Hungary.

The Soviet 10th Guards Rifle Corps of the 46th Army (2nd Ukrainian Front), together with units of the Yugoslav Partisans[34] moving via the Danube—provided more offensive strength from the north-east against the Wehrmacht's position in Belgrade. They cleared the left bank of the Tisa and Danube (in Yugoslavia) and took the town of Pančevo.

Allied forces

Participating in the assault on the capital of Yugoslavia were:[35]

Soviet Union

- 3rd Ukrainian Front

- 4th Guards Mechanised Corps (General Lieutenant T. V. Zhdanov Vladimir Ivanovich)

- 13th Guards Mechanised Brigade (Lieutenant Colonel Obaturov Gennadi Ivanovich)

- 14th Guards Mechanised Brigade (Colonel Nikitin Nicodemius Alekseyevich)

- 15th Guards Mechanised Brigade (Lieutenant Colonel Andrianov Mikhail Alekseyevich)

- 36th Guards Tank Brigade (Colonel Zhukov Peter Semenovich)

- 292nd Guards Self-propelled Artillery Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel Shakhmetov Semen Kondratevich)

- 352nd Guards Heavy Self-propelled Artillery Regiment (Colonel Tiberkov Ivan Markovich);

- 5th Guards Motor Rifle Brigade (Colonel Zavyalov Nikolai Ivanovich);

- 23rd Howitzer Artillery Brigade (Colonel Karpenko Savva Kirillovich) of the 9th Breakthrough Artillery Division (Major General art. Ratov Andrey Ivanovich)

- 42nd Anti-tank destroyer artillery Brigade (Colonel Leonov Constantine Alekseyevich)

- 22nd Anti-aircraft Artillery Division (Colonel Danshin Igor Mikhaylovich)

- 4th Guards Mechanised Corps (General Lieutenant T. V. Zhdanov Vladimir Ivanovich)

- 57th Army

- 75th Rifle Corps (Major General Akimenko Andrian Zakharovich)

- 223rd Rifle Division (Colonel Sagitov Akhnav Gaynutdinovich)

- 236th Rifle Division (Colonel Kulizhskiy Peter Ivanovich)

- 68th Rifle Corps (Major General Shkodunovich Nikolai Nikolayevich)

- 73rd Guards Rifle Division (Major General Kozak Semen Antonovich)

- Danube Military Flotilla

- Brigade of Armoured Boats (Captain Second Rank Derzhavin Pavel Ivanovich)

- 1st Guards Armoured Boats Division (Lieutenant Commander Barbotko Sergey Ignatevich)

- 4th Guards Armoured Boats Division (Senior Lieutenant Butvin Kuzma [Iosifovich])

- Coastal escort force (Major Zidr Klementiy Timofeevich)

- Brigade of Armoured Boats (Captain Second Rank Derzhavin Pavel Ivanovich)

- 17th Air Army

- 10th Assault Air Corps (lieutenant general of aviation Tolstyakov Oleg Viktorovich)

- 295th Fighter Air Division (Colonel Silvestrov Anatoliy Alexandrovich)

- 306th Assault Air Division (Colonel Ivanov Alexander Viktorovich),

- 136th Assault Air Division (part, Colonel Tereckov Nikolai Pavlovich)

- 10th Guards Assault Air Division (Major General of Aviation Vitruk Andrey Nikiforovich)

- 236th Fighter Air Division (Colonel Kudryashov Vasiliy Yakovlevich)

- 288th Fighter Air Division (part, Colonel Smirnov Boris Alexandrovich)

- 10th Assault Air Corps (lieutenant general of aviation Tolstyakov Oleg Viktorovich)

Yugoslavia

- 1st Army Group (General – Lieutenant Colonel Peko Dapčević)

- 1st Proletarian Division (Colonel Vaso Jovanović)

- 6th Proletarian Division (Colonel Đoko Jovanić)

- 5th Assault Division (Colonel Milutin Morača)

- 21st Assault Division (Colonel Miloje Milojević)

- 12th Army Corps (General – Lieutenant Colonel Danilo Lekić)

- 11th Assault Division (Colonel Miloš Šiljegović)

- 16th Assault Division (Colonel Marko Peričin)

- 28th Assault Division (Lieutenant Colonel Radojica Nenezić)

- 36th Assault Division (Lieutenant Colonel Rodoslav Jović)

Bulgaria

By the end of the September the First Army, together with the Bulgarian Second, Third and elements of the Fourth Armies, was in full-scale combat against the German Army along the Bulgaria-Yugoslavia border, with Yugoslavian guerrillas on their left flank and a Soviet force on their right. They consisted from around 340,000 men. By December 1944, the First Army numbered 100,000 men. The First Army took part in the Bulgarian Army's advance northwards into the Balkan Peninsula with logistical support and under command of the Red Army. The First Army, advanced into Serbia, Hungary and Austria in the spring of 1945, despite heavy casualties and bad conditions in the winter. During 1944–45, the Bulgarian First Army was commanded by Lieutenant-General Vladimir Stoychev.

Aftermath

Upon completion of the Belgrade operation, 57th Army with Yugoslav 51st division in November won the bridgehead in Baranja, on the left bank of Danube, causing acute crisis of the German defense. The bridgehead served as a platform for the massive concentration of the 3rd Ukrainian Front troops for the Budapest Offensive. Red Army 68th Rifle Corps participated in the battles on the Kraljevo bridgehead and Syrmian Front until mid-December, to be transferred to Baranja afterwards. Red Army Air Force Group "Vitruk" provided air support on the Yugoslav Front until the end of December.

Yugoslav 1st Army Group continued to push back German forces westwards for some 100 km through Srem, where Germans in mid-December managed to stabilize front.

Having lost Belgrade and Great Morava Valley, German Army Group E was forced to fight for a passage through the mountains of Sandžak and Bosnia, not to reach Drava with its first echelons until mid-February 1945.

A Medal "For the Liberation of Belgrade" was established by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet decree of June 19, 1945.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Krivosheyev 1997.

- ↑ Glantz (1995), p. 299

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 260.

- ↑ p.1116, Dupuy; Belgrade itself was taken on 20 October

- ↑ p.615, Wilmot "[the Red Army] entered Belgrade ... at the same time as Tito's partisans."; p.152, Seaton; "The Russians had no interest in the German occupation forces in Greece and appear to have had very little interest in those retiring northwards through Yugoslavia...Stalin was content to leave to Tito and the Bulgarians the clearing of Yugoslav territory from the enemy."; Library of Congress Country Studies citing "information from Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1919–1945, Arlington, Virginia, 1976": "...Soviet troops crossed the border on October 1, and a joint Partisan-Soviet force liberated Belgrade on October 20." See also http://www.vojska.net/eng/world-war-2/operation/belgrade-1944/

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 83.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 270.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 168.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, pp. 103, 124.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 The Oxford companion to World War II, Ian Dear, Michael Richard Daniell Foot, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-860446-7, p. 134.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 124.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Basil Davidson: PARTISAN PICTURE

- ↑ Schmider 2002, p. 587.

- ↑ Maclean 2002, pp. 437–438.

- ↑ Maclean 2002, pp. 470–497.

- ↑ Report of the High Commander of the Army Group F to the High Command of Wehrmacht Chief of Staff, dated 20 September 1944, National Archive Washington, Record Group 242, T311, Roll 191, frames 637–642.

- ↑ Axis Forces in Yugoslavia 1941–45, Nigel Thomas, K. Mikulan, Darko Pavlović, Osprey Publishing, 1995, ISBN 1-85532-473-3, p. 33.

- ↑ World War II: The Mediterranean 1940–1945, World War II: Essential Histories, Paul Collier, Robert O'Neill, The Rosen Publishing Group, 2010, ISBN 1-4358-9132-5, p. 77.

- ↑ this Army included the Bulgarian Armored Brigade previously equipped and trained by the Wehrmacht

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 103.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 104.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 160.

- ↑ Ivanović 1995, p. 162.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, pp. 168-169.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 200.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 196.

- ↑ pp.215–56, Mitrovski

- ↑ p.666, Glantz

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, p. 199.

- ↑ Biryuzov 1964, pp. 203-204.

- ↑ The composition of the 2nd Army was: Bulgarian Armored Brigade, 8th Infantry Division, 4th Infantry Division, 6th Infantry Division, 12th Infantry Division, parts of the 24th and 26th Infantry Divisions, and the 1st Assault Gun Detachment, pp.166–208, Grechko

- ↑ Belgrade operation – Allied – Order of Battle

- ↑ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/12-yugoslavia.html Dudarenko, M.L., Perechnev, Yu.G., Yeliseev, V.T., et.el., Reference guide "Liberation of cities": reference for liberation of cities during the period of the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945, Moscow, 1985 (Дударенко, М.Л., Перечнев, Ю.Г., Елисеев, В.Т. и др., сост. Справочник «Освобождение городов: Справочник по освобождению городов в период Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945»)

Sources

- Biryuzov, Sergeĭ Semenovich; Hamović, Rade (1964). BEOGRADSKA OPERACIJA. Beograd: Vojni istoriski institut Jugoslovenske narodne armije.

- Dudarenko, M.L., Perechnev, Yu.G., Yeliseev, V.T., et.el., Reference guide "Liberation of cities": reference for liberation of cities during the period of the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945, Moscow, 1985

- Glantz, David, 1986 Art of War symposium, From the Vistula to the Oder: Soviet Offensive Operations – October 1944 – March 1945, A transcript of Proceedings, Center for Land Warfare, US Army War College, 19–23 May 1986

- Glantz, David M. & House, Jonathan (1995), When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler, Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-0899-0.

- Krivosheyev, Grigoriy Fedotovich (1997). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century. Greenhill Books.

- Maclean, Fitzroy (1949). Eastern Approaches. Penguin Group.

- Seaton, Albert, The fall of Fortress Europe 1943–1945, B.T.Batsford Ltd., London, 1981 ISBN 0-7134-1968-7

- Schmider, Klaus (2002). PARTISANENKRIEG IN JUGOSLAWIEN 1941–1944. Hamburg, Berlin, Bonn: Verlag E.S. Mittler & Sohn GmbH. ISBN 3-8132-0794-3.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2002). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia: 1941 - 1945. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0857-6.

- Dupuy, Ernest R., and Dupuy, Trevor N., The encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the present (revised edition), Jane's Publishing Company, London, 1980

- Mitrovski, Boro, Venceslav Glišić and Tomo Ristovski, The Bulgarian Army in Yugoslavia 1941–1945, Belgrade, Medunarodna Politika, 1971

- Wilmot, Chester, The Struggle for Europe, Collins, 1952

- Grechko, A.A., (ed.), Liberation Mission of the Soviet Armed Forces in the Second World War, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1975

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Belgrade Offensive (1944). |

- World War II in Yugoslavia

- Seven anti-Partisan offensives

- Lothar Rendulic

- Resistance during World War II

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||