Behavioral modernity

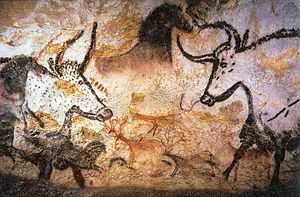

Upper paleolithic, 16,000 years old, cave painting from Lascaux cave in France

|

Behavioral modernity is a term used in anthropology, archeology and sociology to refer to a set of traits that distinguish present day humans and their recent ancestors from both other living primates and other extinct hominid lineages. It is the point at which Homo sapiens began to demonstrate an ability to use complex symbolic thought and express cultural creativity. These developments are often thought to be associated with the origin of language.[1] Elements of behavioral modernity include finely made tools, fishing, long-distance sharing or exchange among groups, self-ornamentation, figurative art, games, music, cooking and burial.

There are two main theories regarding when modern human behavior emerged.[2] One theory holds that behavioral modernity occurred as a sudden event some 50 kya (50,000 years ago) in prehistory, possibly as a result of a major genetic mutation or as a result of a biological reorganization of the brain that led to the emergence of modern human natural languages.[3] Proponents of this theory refer to this event as the Great Leap Forward[4] or the Upper Paleolithic Revolution.

The second theory holds that there was never any single technological or cognitive revolution. Proponents of this view argue that modern human behavior is the result of the gradual accumulation of knowledge, skills and culture occurring over hundreds of thousands of years of human evolution.[5]

Definition

Modern human behavior is observed in cultural universals which are the key elements shared by all groups of people throughout the history of humanity. Examples of elements that may be considered cultural universals are religion, art, dance, singing, music, myth, games, and jokes. While some of these traits distinguish Homo sapiens from other species in their degree of articulation in language based culture, some have analogues in animal ethology.

There is also an important distinction to be made between when humans developed the ability to invent, in contrast to developing the ability to adopt, modern human behavior. As a modern analogy, there is no shortage of musicians in the world trying to compose new and original music, but only a handful every year that successfully manage to compose lasting world wide hit songs; yet essentially all of the other aspiring composer musicians can almost trivially learn to play those hit songs once they've heard them (with analogous undertakings in literature, art, science and technology etc.). A dramatic and sudden increase in complexity of human behavior is thus fully plausible even if significantly less than 1% of humanity developed the genetic ability to "invent", provided that the remaining 99% had no significant problems with "adopting" those inventions. There is potentially an evolutionary abyss between inventing and adopting; for instance, Homo erectus and Homo ergaster produced with little advancement essentially the same sharpened stone tools for over a million years, but there is no scientific evidence at hand that could prove that they were incapable of producing composite stone tools, such as spears, if shown how to do so.

It is thus not established if the early Homo sapiens had the genetic requirements to be able to adopt modern human behavior, such as religious beliefs, through cultural interaction. If indeed the early Homo sapiens had the ability to learn modern human behavior, once invented by other groups, there is no geographic restriction where modern behavior originated. However, if the early Homo sapiens hypothetically were genetically inhibited from adopting modern human behaviors, since cultural universals are found in all cultures including some of the most isolated indigenous groups, these traits must have evolved or have been invented in Africa prior to the exodus.[6][7][8][9]

Classic archaeologically accessible evidence of behavioral modernity includes:

- finely made tools

- fishing

- evidence of long-distance sharing or exchange among groups

- systematic use of pigment (such as ochre) and jewelry for decoration or self-ornamentation

- figurative art (cave paintings, petroglyphs, figurines)

- game playing

- dance, singing, and prehistoric music

- foods being cooked and seasoned instead of being consumed raw

- burial

A more terse definition of the evidence is the behavioral B's: blades, beads, burials, bone toolmaking, and beauty.[10]

Timing

Whether modern behavior emerged as a single event or gradually is the subject of vigorous debate.

Great leap forward

Most advocates of this theory argue that the great leap forward occurred sometime between 50-40 kya in Africa or Europe, or perhaps simultaneously throughout the occupied world. (Some argue for an earlier date and a slower radiation, urging evidence for advanced tool-making (e.g., pyrolytic and bone tools) and abstract designs at Blombos Cave and other sites along the South African coast by at least 80 kya.,[1] see continuity hypothesis, below.) Great leap forward advocates argue that humans who lived before the leap were behaviorally primitive, indistinguishable from other later extinct hominids such as the Neanderthals or Homo erectus. Proponents of this view base their evidence on the abundance of complex artifacts, such as artwork and bone tools of the Upper Paleolithic, that appear in the fossil record after 50 kya.[11] They argue that such artifacts are absent from the fossil record from before 50 kya, indicating that earlier hominids lacked the cognitive skills required to invent such artifacts.

Jared Diamond states that humans of the Acheulean and Mousterian cultures lived in an apparent stasis, experiencing little cultural change. This was followed by a sudden flowering of fine toolmaking, sophisticated weaponry, sculpture, cave painting, body ornaments, and long-distance trade.[12] Humans also expanded into hitherto uninhabited environments, such as Australia and Northern Eurasia.[12]

According to this model, the emergence of behaviorally modern humans postdates the emergence of anatomically modern humans by over 100 ky.

Continuity hypothesis

Proponents of the continuity hypothesis hold that no single genetic or biological change is responsible for the appearance of modern behavior. They contend that modern human behavior is the result of sociocultural and sociobiological evolution occurring over hundreds of thousands of years. They further dispute that anatomical modernity predates behavioral modernity, stating that changes in human anatomy and behavioral changes occurred in tandem.[5]

Continuity theorists base their assertions on evidence of aspects of modern behavior that can be seen in the Middle Stone Age (approximately 250-50 kya) at a number of sites in Africa and the Levant. For example, a possible burial at Qafzeh is Middle Stone Age (MSA) having been dated to 90 kya. The usage of pigment is noted at several MSA sites in Africa dating back more than 100 kya. At Pinnacle Point cave, Marean's team found evidence that tool makers may have understood the process of careful heating needed for converting silcrete into an easily flaked form 73 kya, and possibly more than 164 kya. Prior to this, it was widely believed that earliest known use of this technology was in Europe 25 kya.[13][14]

The Schöningen spears, associated with Homo heidelbergensis, and their associated finds are evidence of complex technological skills at 300,000 years ago and are the first incontrovertible evidence for active big game hunting. It is doubtful that a successful hunt for quickly fleeing gregarious animals could have occurred without sophisticated hunting strategies, a complex social structure and developed forms of communication (language ability). H. heidelbergensis already had intellectual and cognitive skills like anticipatory planning, thinking and acting that in the past were only attributed to modern man.[15][16]

Some continuity theorists also argue that the rapid pace of cultural evolution during the Upper Paleolithic transition may have been triggered by adverse environmental conditions such as aridity arising from glacial maxima.[1]

See also

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Mellars, Paul (2006). "Why did modern human populations disperse from Africa ca. 60,000 years ago? A new model". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103 (25): 9381–6. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.9381M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510792103. PMC 1480416. PMID 16772383.

- ↑ Mayell, Hillary (2003). "When Did "Modern" Behavior Emerge in Humans?".

- ↑ Ehrlich, Paul R. (2002). Human Natures: Genes, Cultures, and the Human Prospect. Island Press. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-1-55963-779-4.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared (1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fate of Human Societies. W. W. Norton. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-393-31755-8.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mcbrearty (2000). "The revolution that wasn’t: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior" (PDF).

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (2003-07-15). "leap to language". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ↑ Buller, David (2005). Adapting Minds: Evolutionary Psychology and the Persistent Quest for Human Nature. PMIT Press. p. 468. ISBN 0-262-02579-5.

- ↑ "80,000-year-old Beads Shed Light on Early Culture". Livescience.com. 2007-06-18. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ↑ "three distinct human populations". Accessexcellence.org. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ↑ "William H. Calvin, A Brief History of the Mind (Oxford University Press 2004), chapter 9". Williamcalvin.com. 2003-09-01. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ↑ AP Spanish cave paintings shown as oldest in world 14 June 2012

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Diamond, Jared (1992). The Third Chimpanzee. Harper Perennial. pp. 47–57. ISBN 978-0-06-098403-8.

- ↑ Brown, Kyle S.; Marean, Curtis W.; Herries, Andy I.R.; Jacobs, Zenobia; Tribolo, Chantal; Braun, David; Roberts, David L.; Meyer, Michael C.; Bernatchez, J., (August 14, 2009), "Fire as an Engineering Tool of Early Modern Humans", Science 325: 859–862, Bibcode:2009Sci...325..859B, doi:10.1126/science.1175028

- ↑ "Early modern humans use fire to engineer tools from stone", Phys Org (Arizona State University), 13 August 2009, retrieved 4 April 2013

- ↑ Thieme H. 2007. Der große Wurf von Schöningen: Das neue Bild zur Kultur des frühen Menschen in: Thieme H. (ed.) 2007: Die Schöninger Speere – Mensch und Jagd vor 400 000 Jahren. S. 224-228 Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart ISBN 3-89646-040-4

- ↑ Haidle M.N. 2006: Menschenaffen? Affenmenschen? Mensch! Kognition und Sprache im Altpaläolithikum. In Conard N.J. (ed.): Woher kommt der Mensch. S. 69-97. Attempto Verlag. Tübingen ISBN 3-89308-381-2

External links

- Steven Mithen (1999), The Prehistory of the Mind: The Cognitive Origins of Art, Religion and Science, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-28100-0.

- Artifacts in Africa Suggest An Earlier Modern Human

- Tools point to African origin for human behaviour

- Key Human Traits Tied to Shellfish Remains, nytimes 2007/10/18

- "Python Cave" Reveals Oldest Human Ritual, Scientists Suggest

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||