Becker's muscular dystrophy

| Becker's muscular dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | G71.0 |

| ICD-9 | 359.1 |

| OMIM | 300376 |

| DiseasesDB | 1280 |

| MedlinePlus | 000706 |

| eMedicine | pmr/14 |

| Patient UK | Becker's muscular dystrophy |

Becker muscular dystrophy (also known as Benign pseudohypertrophic muscular dystrophy) is an X-linked recessive inherited disorder characterized by slowly progressive muscle weakness of the legs and pelvis.

It is a type of dystrophinopathy, which includes a spectrum of muscle diseases in which there is insufficient dystrophin produced in the muscle cells, resulting in instability in the structure of muscle cell membrane. This is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene, which encodes the protein dystrophin. Becker muscular dystrophy is related to Duchenne muscular dystrophy in that both result from a mutation in the dystrophin gene, but in Duchenne muscular dystrophy no functional dystrophin is produced making DMD much more severe than BMD.

Eponym

Becker Muscular Dystrophy is named after the German doctor Peter Emil Becker (November 23, 1908 Hamburg, Germany - 2000).[1][2][3]

Genetics

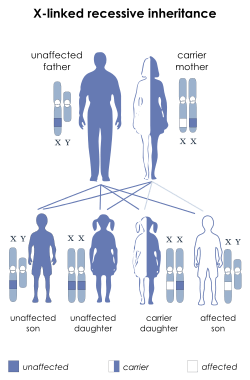

The disorder is inherited with an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern. The gene is located on the X chromosome. Since women have two X chromosomes, if one X chromosome has the non-working gene, the second X chromosome will have a working copy of the gene to compensate. Because of this ability to compensate, women rarely develop symptoms. However, they may do so due to mosaicism. For example, carrier females of mutations are at increased risk for dilated cardiomyopathy. Since men have an X and a Y chromosome and because they don't have another X to compensate for the defective gene, they will develop symptoms if they inherit the non-working gene.

All dystrophinopathies are inherited in an X-linked recessive manner. The risk to the siblings of an affected individual depends upon the carrier status of the mother. Carrier females have a 50% chance of passing the DMD mutation in each pregnancy. Sons who inherit the mutation will be affected; daughters who inherit the mutation will be carriers. Men who have Becker muscular dystrophy can have children, and all their daughters are carriers, but none of the sons will inherit their father's mutation. Prenatal testing through amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS) for pregnancies at risk is possible if the DMD mutation is found in a family member or if informative linked markers have been identified. A significant number of Becker muscular dystrophy mutations are spontaneous and are not inherited from a parent.

Becker muscular dystrophy occurs in approximately 3 to 6 in 100,000 male births, making it much less common than Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Symptoms usually appear in men at about ages 8–25, but may sometimes begin later. Patients can lose the ability to walk as early as age 15 in the very rare severe form.

Genetic counseling may be advisable when potential carriers or patients want to have children. Sons of a man with Becker muscular dystrophy do not develop the disorder, but daughters will be carriers (and some carriers can experience some symptoms of muscular dystrophy). The daughters' sons may develop the disorder.

Symptoms

- Muscle weakness, slowly progressive (Difficulty running, hopping, jumping; difficulty walking. However, ability to walk may or may not continue well into adulthood

- Severe upper extremity and trunk muscle weakness may be seen as well.

- Toe-walking (walking on toes; also known as equinus)

- Use of Gower's Maneuver or a modified form of Gower's Maneuver to get up from floor.

- Frequent falls

- Difficulty breathing

- Skeletal deformities, chest and back (scoliosis)

- Muscle deformities (contractions of heels, legs; Pseudohypertrophy of calf muscles)

- Fatigue

- Heart disease, particularly dilated cardiomyopathy

- Elevated CPK (creatine phosphokinase) levels in blood: Elevated CPK levels are more common at younger ages and decreases later in life, perhaps because muscle degeneration occurs more rapidly at younger ages, when there is also more muscle mass to deteriorate.

People with this disorder typically experience progressive muscle weakness of the leg and pelvis muscles, which is associated with a loss of muscle mass (wasting). Muscle weakness also occurs in the arms, neck, and other areas, but not as noticeably severe as in the lower half of the body.

Calf muscles initially enlarge during the ages of 5-15 (an attempt by the body to compensate for loss of muscle strength), but the enlarged muscle tissue is eventually replaced by fat and connective tissue (pseudohypertrophy) as the legs become less used (use of wheelchair).

Muscle contractions, which may be painful, occur in the legs and heels, causing inability to use the muscles because of shortening of muscle fibers and fibrosis of connective tissue. Bones may develop abnormally, causing skeletal deformities of the chest and other areas.

Cardiomyopathy (damage to the heart) does not occur as commonly with this disorder as it does with Duchenne's muscular dystrophy.

Signs and tests

The pattern of symptom development resembles that of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, but with a later, and much slower rate of progression. Noticeable signs of Muscular Dystrophy also include the lack of pectoral and upper arm muscles, especially when the disease is unnoticed through the early teen years (some men are not diagnosed with BMD until they are in their thirties). Muscle wasting begins in the legs and pelvis (or core), then progresses to the muscles of the shoulders and neck, followed by loss of arm muscles and respiratory muscles. Calf muscle enlargement (pseudohypertrophy) is quite obvious. Cardiomyopathy may occur, but the development of congestive heart failure or arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats) is rare.

- Loss of ambulation (loss of ability to walk) may not occur until the person is in his fifties.

- Creatine kinase (CPK) levels may be elevated.

- An electromyography (EMG) shows that weakness is caused by destruction of muscle tissue rather than by damage to nerves.

- Genetic testing

- A muscle biopsy (immunohistochemistry or immunoblotting) or genetic test (blood test) confirms the diagnosis.

Treatment

There is no known cure for Becker muscular dystrophy yet. Treatment is aimed at control of symptoms to maximize the quality of life.

Activity is encouraged. Inactivity (such as bed rest) or sitting down for too long on plane or car rides can worsen the muscle disease. Physical therapy may be helpful to maintain muscle strength. Orthopedic appliances such as braces and wheelchairs may improve mobility and self-care.

Immunosuppressant steroids like Prednisone have been known to help slow the progression of Becker Muscular Dystrophy. The drug contributes to an increased production of the protein Utrophin which closely resembles Dystrophin, the protein that is defective in BMD. IVIG has proved better in the long term, but its high cost makes it difficult for both medical facilities and families to use it as a solid treatment.

A Utrophin up-regulation drug SMT C1100 by UK Company Summit for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) has successfully completed phase 1b trials in the UK and is expected to enter further clinical trials in 2014. This drug could also be used for BMD.

A hepatitis C drug, "Debio-025", that has proven safe for use in Europe shows much promise for halting the muscle necrosis seen in the disease. The investigational drug Debio-025 is a known inhibitor of the protein cyclophilin D, which regulates the swelling of mitochondria in response to cellular injury. Researchers decided to test the drug in mice engineered to carry MD after earlier laboratory tests showed deleting a gene that encodes cycolphilin D reduced swelling and reversed or prevented the disease’s muscle-damaging characteristics. The mice were engineered as models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and forms caused by a deficiency of two structural proteins, delta-sarcoglycan and laminin alpha2. Treatment with Debio-025 was reported to reduce mitochondrial swelling and necrotic manifestations in mice with muscular dystrophy. Debio-025 has passed Phase II clinical trials in Europe.

During the onset of muscular dystrophy, the loss of certain proteins critical to muscle function – such as dystrophin – can lead to contraction-related micro-tears in muscle fibers and an influx of calcium around muscle tissue. When this happens, cyclophilin D is instructed to make the membranes of mitochondria more permeable. This causes mitochondria to be flooded by calcium and reorganize, swell and eventually rupture. This triggers cell death in muscle fibers and leads to the progressive muscle weakness, wasting and often early death associated with muscular dystrophy.

Prognosis

The progression of Becker muscular dystrophy is highly variable—much more so than Duchenne muscular dystrophy. There is also a form that may be considered as an intermediate between Duchenne and Becker MD (mild DMD or severe BMD). Severity of the disease may be indicated by age of patient at the onset of the disease. One study showed that there may be two distinct patterns of progression in Becker muscular dystrophy: one subgroup which experiences its onset at around age 7 to 8 years of age- this group typically has more cardiac involvement and has trouble climbing stairs by age 20; the other subgroup, which has its onset at around age 12, typically has significantly less cardiac involvement and can still easily climb stairs by age 20.[4] The mean age of onset is age 11, with variation from age 2 to 21.[5]

Becker's muscular dystrophy results in slowly progressive disability, and patients eventually use a cane or wheelchair. Death can occur from age 40 but some patients enjoy a nearly normal lifespan.

Quality of Life

The quality of life for patients with Becker's muscular dystrophy can be impacted by the symptoms of the disorder. But with assistive devices, independence can be maintained. People affected by Becker's muscular dystrophy can still drive, work, own businesses, start families, and maintain active lifestyles. Those affected by the disorder can also still participate in sports for the disabled, such as wheelchair tennis, Power Soccer, and sled hockey.

Complications

- Deformities (particularly kyphosis)

- Permanent, progressive disability manifested as decreased mobility or decreased ability to care for self

- Mental impairment - However, this is much less common in BMD than it is in DMD.

- Cardiomyopathy

- Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy

- Pneumonia or other respiratory infections

- Respiratory failure

References

- ↑ synd/915 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Becker PE, Kiener F (1955). "[A new x-chromosomal muscular dystrophy.]". Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr (in German) 193 (4): 427–48. PMID 13249581.

- ↑ Becker PE (1957). "[New results of genetics of muscular dystrophy.]". Acta Genet Stat Med (in German) 7 (2): 303–10. PMID 13469170.

- ↑ Delisa, Joel A; Gans, Bruce M; Walsh, Nicholas E (2005). "Physical medicine and rehabilitation: Principles and practice". ISBN 978-0-7817-4130-9.

- ↑ http://www.patient.co.uk/showdoc/40001349/

Events

External links

- www.beckerMD.org - Website for BMD patients and caregivers

- Muscular Dystrophy; Becker Type; BMD - Information on Molecular Genetics in Becker Muscular Dystrophy from NCBI (OMIM)

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Dystrophinopathies

- Muscular Dystrophy Campaign - UK charity that fights all forms of muscle disease.

- Dystrophy.com - Extensive information about muscular dystrophies

- Parent Project USA

- Muscular Dystrophy Association's website in Greece

- Life With Muscular Dystrophy

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||