Beauville–Laszlo theorem

In mathematics, the Beauville–Laszlo theorem is a result in commutative algebra and algebraic geometry that allows one to "glue" two sheaves over an infinitesimal neighborhood of a point on an algebraic curve. It was proved by Arnaud Beauville and Yves Laszlo (1995).

The theorem

Although it has implications in algebraic geometry, the theorem is a local result and is stated in its most primitive form for commutative rings. If A is a ring and f is a nonzero element of A, then we can form two derived rings: the localization at f, Af, and the completion at Af, Â; both are A-algebras. In the following we assume that f is a non-zero divisor. Geometrically, A is viewed as a scheme X = Spec A and f as a divisor (f) on Spec A; then Af is its complement Df = Spec Af, the principal open set determined by f, while  is an "infinitesimal neighborhood" D = Spec  of (f). The intersection of Df and Spec  is a "punctured infinitesimal neighborhood" D0 about (f), equal to Spec  ⊗A Af = Spec Âf.

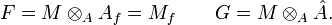

Suppose now that we have an A-module M; geometrically, M is a sheaf on Spec A, and we can restrict it to both the principal open set Df and the infinitesimal neighborhood Spec Â, yielding an Af-module F and an Â-module G. Algebraically,

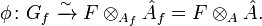

(Despite the notational temptation to write  , meaning the completion of the A-module M at the ideal Af, unless A is noetherian and M is finitely-generated, the two are not in fact equal. This phenomenon is the main reason that the theorem bears the names of Beauville and Laszlo; in the noetherian, finitely-generated case, it is, as noted by the authors, a special case of Grothendieck's faithfully flat descent.) F and G can both be further restricted to the punctured neighborhood D0, and since both restrictions are ultimately derived from M, they are isomorphic: we have an isomorphism

, meaning the completion of the A-module M at the ideal Af, unless A is noetherian and M is finitely-generated, the two are not in fact equal. This phenomenon is the main reason that the theorem bears the names of Beauville and Laszlo; in the noetherian, finitely-generated case, it is, as noted by the authors, a special case of Grothendieck's faithfully flat descent.) F and G can both be further restricted to the punctured neighborhood D0, and since both restrictions are ultimately derived from M, they are isomorphic: we have an isomorphism

Now consider the converse situation: we have a ring A and an element f, and two modules: an Af-module F and an Â-module G, together with an isomorphism φ as above. Geometrically, we are given a scheme X and both an open set Df and a "small" neighborhood D of its closed complement (f); on Df and D we are given two sheaves which agree on the intersection D0 = Df ∩ D. If D were an open set in the Zariski topology we could glue the sheaves; the content of the Beauville–Laszlo theorem is that, under one technical assumption on f, the same is true for the infinitesimal neighborhood D as well.

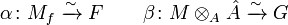

Theorem: Given A, f, F, G, and φ as above, if G has no f-torsion, then there exist an A-module M and isomorphisms

consistent with the isomorphism φ: φ is equal to the composition

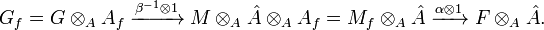

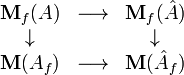

The technical condition that G has no f-torsion is referred to by the authors as "f-regularity". In fact, one can state a stronger version of this theorem. Let M(A) be the category of A-modules (whose morphisms are A-module homomorphisms) and let Mf(A) be the full subcategory of f-regular modules. In this notation, we obtain a commutative diagram of categories (note Mf(Af) = M(Af)):

in which the arrows are the base-change maps; for example, the top horizontal arrow acts on objects by M → M ⊗A Â.

Theorem: The above diagram is a cartesian diagram of categories.

Global version

In geometric language, the Beauville–Laszlo theorem allows one to glue sheaves on a one-dimensional affine scheme over an infinitesimal neighborhood of a point. Since sheaves have a "local character" and since any scheme is locally affine, the theorem admits a global statement of the same nature. The version of this statement that the authors found noteworthy concerns vector bundles:

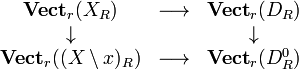

Theorem: Let X be an algebraic curve over a field k, x a k-rational smooth point on X with infinitesimal neighborhood D = Spec k[[t]], R a k-algebra, and r a positive integer. Then the category Vectr(XR) of rank-r vector bundles on the curve XR = X ×Spec k Spec R fits into a cartesian diagram:

This entails a corollary stated in the paper:

Corollary: With the same setup, denote by Triv(XR) the set of triples (E, τ, σ), where E is a vector bundle on XR, τ is a trivialization of E over (X \ x)R (i.e., an isomorphism with the trivial bundle O(X - x)R), and σ a trivialization over DR. Then the maps in the above diagram furnish a bijection between Triv(XR) and GLr(R((t))) (where R((t)) is the formal Laurent series ring).

The corollary follows from the theorem in that the triple is associated with the unique matrix which, viewed as a "transition function" over D0R between the trivial bundles over (X \ x)R and over DR, allows gluing them to form E, with the natural trivializations of the glued bundle then being identified with σ and τ. The importance of this corollary is that it shows that the affine Grassmannian may be formed either from the data of bundles over an infinitesimal disk, or bundles on an entire algebraic curve.

References

- Beauville, Arnaud; Laszlo, Yves (1995), "Un lemme de descente", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. Série I. Mathématique 320 (3): 335–340, ISSN 0764-4442, retrieved 2008-04-08