Beat (acoustics)

In acoustics, a beat is an interference between two sounds of slightly different frequencies, perceived as periodic variations in volume whose rate is the difference between the two frequencies.

With tuning instruments that can produce sustained tones, beats can readily be recognized. Tuning two tones to a unison will present a peculiar effect: when the two tones are close in pitch but not identical, the difference in frequency generates the beating. The volume varies like in a tremolo as the sounds alternately interfere constructively and destructively. As the two tones gradually approach unison, the beating slows down and may become so slow as to be imperceptible.

Mathematics and physics of beat tones

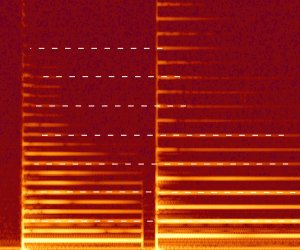

This phenomenon manifests acoustically. If a graph is drawn to show the function corresponding to the total sound of two strings, it can be seen that maxima and minima are no longer constant as when a pure note is played, but change over time: when the two waves are nearly 180 degrees out of phase the maxima of each cancel the minima of the other, whereas when they are nearly in phase their maxima sum up, raising the perceived volume.

It can be proven (see List of trigonometric identities) that the successive values of maxima and minima form a wave whose frequency equals the difference between the frequencies of the two starting waves. Let's demonstrate the simplest case, between two sine waves of unit amplitude:

If the two starting frequencies are quite close (for example, a difference of approximately twelve hertz[2]), the frequency of the cosine of the right side of the expression above, that is (f1−f2)/2, is often too slow(low) to be perceived as a pitch. Instead, it is perceived as a periodic variation of the first in the expression above (it can be said that the lower frequency cosine term, i.e. the second one, is an envelope for the faster wave, i.e. the first cosine term), whose frequency is (f1 + f2)/2, that is, the average of the two frequencies. However, because the human ear is not sensitive to the phase, only the amplitude or intensity of the sound, only the absolute value of the envelope is heard. Therefore, subjectively, the frequency of the envelope seems to have twice the frequency of the cosine, which means the audible beat frequency is:

This can be seen on the diagram on the right.

A physical interpretation is that when  equals one, the two waves are in phase and they interfere constructively. When it is zero, they are out of phase and interfere destructively. Beats occur also in more complex sounds, or in sounds of different volumes, though calculating them mathematically is not so easy.

equals one, the two waves are in phase and they interfere constructively. When it is zero, they are out of phase and interfere destructively. Beats occur also in more complex sounds, or in sounds of different volumes, though calculating them mathematically is not so easy.

Beating can also be heard between notes that are near to, but not exactly, a harmonic interval, due to some harmonic of the first note beating with a harmonic of the second note. For example, in the case of perfect fifth, the third harmonic (i.e. second overtone) of the bass note beats with the second harmonic (first overtone) of the other note. As well as with out-of tune notes, this can also happen with some correctly tuned equal temperament intervals, because of the differences between them and the corresponding just intonation intervals: see Harmonic series (music)#Harmonics and tuning.

Uses

Musicians commonly use interference beats to objectively check tuning at the unison, perfect fifth, or other simple harmonic intervals. Piano and organ tuners even use a method involving counting beats, aiming at a particular number for a specific interval.

The composer Alvin Lucier has written many pieces that feature interference beats as their main focus. Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi, whose style is grounded on microtonal oscillations of unisons, extensively explored the textural effects of interference beats, particularly in his late works such as the violin solos Xnoybis (1964) and L'âme ailée / L'âme ouverte (1973), which feature them prominently (note that Scelsi treated and notated each string of the instrument as a separate part, so that his violin solos are effectively quartets of one-strings, where different strings of the violin may be simultaneously playing the same note with microtonal shifts, so that the interference patterns are generated). Composer Phill Niblock's music is entirely based on beating caused by microtonal differences.

Binaural beats

Binaural beats are heard when the right ear listens to a slightly different tone than the left ear. Here, the tones do not interfere physically, but are summed by the brain in the olivary nucleus. This effect is related to the brain's ability to locate sounds in three dimensions.

Sample

|

Beating waveforms (high frequency)

300 Hz A3 (left channel) and 310 Hz G#3 (right channel) beating at 12.35 Hz |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

|

Beating waveforms (low frequency)

220 Hz A3 and 222 Hz tone beating at 2.0 Hz |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

See also

- Envelope (waves)

- Voix céleste

- Gamelan tuning

- Heterodyne

- Interference

- Consonance and dissonance

- Moiré pattern, a form of spatial interference that generates new frequencies.

References

- ↑ "Interference beats and Tartini tones", Physclips, UNSW.edu.au.

- ↑ "Acoustics FAQ", UNSW.edu.au.

External links

- Java applet, MIT

- Acoustics and Vibration Animations, D.A. Russell, Kettering University

- A Java applet showing the formation of beats due to the interference of two waves of slightly different frequencies

- Yet another interactive Java applet; also shows equation of combined waves, including phase angle.

- Lissajous Curves: Interactive simulation of graphical representations of musical intervals, beats, interference, vibrating strings

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||