Bayes' rule

In probability theory and applications, Bayes' rule relates the odds of event  to the odds of event

to the odds of event  , before (prior to) and after (posterior to) conditioning on another event

, before (prior to) and after (posterior to) conditioning on another event  . The odds on

. The odds on  to event

to event  is simply the ratio of the probabilities of the two events. The prior odds is the ratio of the unconditional or prior probabilities, the posterior odds is the ratio of conditional or posterior probabilities given the event

is simply the ratio of the probabilities of the two events. The prior odds is the ratio of the unconditional or prior probabilities, the posterior odds is the ratio of conditional or posterior probabilities given the event  . The relationship is expressed in terms of the likelihood ratio or Bayes factor,

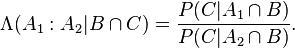

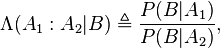

. The relationship is expressed in terms of the likelihood ratio or Bayes factor,  . By definition, this is the ratio of the conditional probabilities of the event

. By definition, this is the ratio of the conditional probabilities of the event  given that

given that  is the case or that

is the case or that  is the case, respectively. The rule simply states: posterior odds equals prior odds times Bayes factor (Gelman et al., 2005, Chapter 1).

is the case, respectively. The rule simply states: posterior odds equals prior odds times Bayes factor (Gelman et al., 2005, Chapter 1).

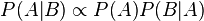

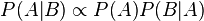

When arbitrarily many events  are of interest, not just two, the rule can be rephrased as posterior is proportional to prior times likelihood,

are of interest, not just two, the rule can be rephrased as posterior is proportional to prior times likelihood,  where the proportionality symbol means that the left hand side is proportional to (i.e., equals a constant times) the right hand side as

where the proportionality symbol means that the left hand side is proportional to (i.e., equals a constant times) the right hand side as  varies, for fixed or given

varies, for fixed or given  (Lee, 2012; Bertsch McGrayne, 2012). In this form it goes back to Laplace (1774) and to Cournot (1843); see Fienberg (2005).

(Lee, 2012; Bertsch McGrayne, 2012). In this form it goes back to Laplace (1774) and to Cournot (1843); see Fienberg (2005).

Bayes' rule is an equivalent way to formulate Bayes' theorem. If we know the odds for and against  we also know the probabilities of

we also know the probabilities of  . It may be preferred to Bayes' theorem in practice for a number of reasons.

. It may be preferred to Bayes' theorem in practice for a number of reasons.

Bayes' rule is widely used in statistics, science and engineering, for instance in model selection, probabilistic expert systems based on Bayes networks, statistical proof in legal proceedings, email spam filters, and so on (Rosenthal, 2005; Bertsch McGrayne, 2012). As an elementary fact from the calculus of probability, Bayes' rule tells us how unconditional and conditional probabilities are related whether we work with a frequentist interpretation of probability or a Bayesian interpretation of probability. Under the Bayesian interpretation it is frequently applied in the situation where  and

and  are competing hypotheses, and

are competing hypotheses, and  is some observed evidence. The rule shows how one's judgement on whether

is some observed evidence. The rule shows how one's judgement on whether  or

or  is true should be updated on observing the evidence

is true should be updated on observing the evidence  (Gelman et al., 2003).

(Gelman et al., 2003).

The rule

Single event

Given events  ,

,  and

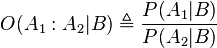

and  , Bayes' rule states that the conditional odds of

, Bayes' rule states that the conditional odds of  given

given  are equal to the marginal odds of

are equal to the marginal odds of  multiplied by the Bayes factor or likelihood ratio

multiplied by the Bayes factor or likelihood ratio  :

:

where

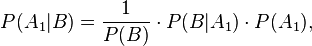

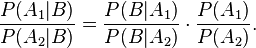

Here, the odds and conditional odds, also known as prior odds and posterior odds, are defined by

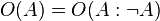

In the special case that  and

and  , one writes

, one writes  , and uses a similar abbreviation for the Bayes factor and for the conditional odds. The odds on

, and uses a similar abbreviation for the Bayes factor and for the conditional odds. The odds on  is by definition the odds for and against

is by definition the odds for and against  . Bayes' rule can then be written in the abbreviated form

. Bayes' rule can then be written in the abbreviated form

or in words: the posterior odds on  equals the prior odds on

equals the prior odds on  times the likelihood ratio for

times the likelihood ratio for  given information

given information  . In short, posterior odds equals prior odds times likelihood ratio.

. In short, posterior odds equals prior odds times likelihood ratio.

The rule is frequently applied when  and

and  are two competing hypotheses concerning the cause of some event

are two competing hypotheses concerning the cause of some event  . The prior odds on

. The prior odds on  , in other words, the odds between

, in other words, the odds between  and

and  , expresses our initial beliefs concerning whether or not

, expresses our initial beliefs concerning whether or not  is true. The event

is true. The event  represents some evidence, information, data, or observations. The likelihood ratio is the ratio of the chances of observing

represents some evidence, information, data, or observations. The likelihood ratio is the ratio of the chances of observing  under the two hypotheses

under the two hypotheses  and

and  . The rule tells us how our prior beliefs concerning whether or not

. The rule tells us how our prior beliefs concerning whether or not  is true needs to be updated on receiving the information

is true needs to be updated on receiving the information  .

.

Many events

If we think of  as arbitrary and

as arbitrary and  as fixed then we can rewrite Bayes' theorem

as fixed then we can rewrite Bayes' theorem  in the form

in the form  where the proportionality symbol means that, as

where the proportionality symbol means that, as  varies but keeping

varies but keeping  fixed, the left hand side is equal to a constant times the right hand side.

fixed, the left hand side is equal to a constant times the right hand side.

In words posterior is proportional to prior times likelihood. This version of Bayes' theorem was first called "Bayes' rule" by Cournot (1843). Cournot popularized the earlier work of Laplace (1774) who had independently discovered Bayes' rule. The work of Bayes was published posthumously (1763) but remained more or less unknown till Cournot drew attention to it; see Fienberg (2006).

Bayes' rule may be preferred to the usual statement of Bayes' theorem for a number of reasons. One is that it is intuitively simpler to understand. Another reason is that normalizing probabilities is sometimes unnecessary: one sometimes only needs to know ratios of probabilities. Finally, doing the normalization is often easier to do after simplifying the product of prior and likelihood by deleting any factors which do not depend on  , so we do not need to actually compute the denominator

, so we do not need to actually compute the denominator  in the usual statement of Bayes' theorem

in the usual statement of Bayes' theorem  .

.

In Bayesian statistics, Bayes' rule is often applied with a so-called improper prior, for instance, a uniform probability distribution over all real numbers. In that case, the prior distribution does not exist as a probability measure within conventional probability theory, and Bayes' theorem itself is not available.

Series of events

Bayes' rule may be applied a number of times. Each time we observe a new event, we update the odds between the events of interest, say  and

and  by taking account of the new information. For two events (information, evidence)

by taking account of the new information. For two events (information, evidence)  and

and  ,

,

where

In the special case of two complementary events  and

and  , the equivalent notation is

, the equivalent notation is

Derivation

Consider two instances of Bayes' theorem:

Combining these gives

Now defining

this implies

A similar derivation applies for conditioning on multiple events, using the appropriate extension of Bayes' theorem

Examples

Frequentist example

Consider the drug testing example in the article on Bayes' theorem.

The same results may be obtained using Bayes' rule. The prior odds on an individual being a drug-user are 199 to 1 against, as  and

and  . The Bayes factor when an individual tests positive is

. The Bayes factor when an individual tests positive is  in favour of being a drug-user: this is the ratio of the probability of a drug-user testing positive, to the probability of a non-drug user testing positive. The posterior odds on being a drug user are therefore

in favour of being a drug-user: this is the ratio of the probability of a drug-user testing positive, to the probability of a non-drug user testing positive. The posterior odds on being a drug user are therefore  , which is very close to

, which is very close to  . In round numbers, only one in three of those testing positive are actually drug-users.

. In round numbers, only one in three of those testing positive are actually drug-users.

External links

- Bessière, P, Mazer, E, Ahuactzin, JM and Mekhnacha, K (2013), "Bayesian Programming", CRC Press.

- Fienberg, SE (2006), "When did Bayesian inference become "Bayesian"?"", Bayesian analysis vol. 1, nr. 1, pp. 1-40.

- Gelman, A, Carlin, JB, Stern, HS and Rubin, DB (2003), "Bayesian Data Analysis", Second Edition, CRC Press.

- Lee, PM (2012), "Bayesian Statistics: An Introduction", Wiley.

- McGrayne, SB (2012), "The Theory That Would Not Die: How Bayes' Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant from Two Centuries of Controversy", Yale University Press.

- The on-line textbook: Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms, by MacKay, DJC, discusses Bayesian model comparison in Chapters 3 and 28.

- Rosenthal, JS (2005): Struck by Lightning: the Curious World of Probabilities. Harper Collings 2005, ISBN 978-0-00-200791-7.

- Stone, JV (2013), "Bayes’ Rule: A Tutorial Introduction to Bayesian Analysis", Download chapter 1, Sebtel Press, England.