Bay Area Rapid Transit

| |||

|

A Pittsburg / Bay Point bound train at Walnut Creek in July 2008. | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Locale |

San Francisco Bay Area Counties: Alameda, Contra Costa, San Francisco, and San Mateo | ||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | ||

| Number of lines |

6 lines

| ||

| Number of stations |

45 (plus 4 under construction, 9 planned/proposed) | ||

| Daily ridership |

422,490 weekdays 211,288 Saturdays 158,855 Sundays (September 2014 average)[1] | ||

| Annual ridership | 117.1 million (FY 2014)[2] | ||

| Headquarters |

Kaiser Center Oakland, California | ||

| Website | Bay Area Rapid Transit | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | September 11, 1972 | ||

| Operator(s) | San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District | ||

| Number of vehicles | 669[3][4] | ||

| Train length | 3-10 cars | ||

| Headway | 15-20 mins (by line); 3-8 mins (between trains at busiest stations) | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 104 mi (167 km)[3] | ||

| Track gauge |

5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm)[3] (Indian gauge) | ||

| Electrification | Third rail, 1000 V DC[3][4] | ||

| Top speed | 80 mph (130 km/h)[3] | ||

| |||

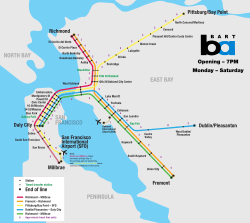

Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) is a rapid transit system serving the San Francisco Bay Area. The heavy-rail public transit and subway system connects San Francisco with cities in the East Bay and suburbs in northern San Mateo County. BART's rapid transit system operates five routes on 104 miles (167 km) of line, with 44 stations in four counties. With an average of 422,490 weekday passengers, 211,288 Saturday passengers, and 158,855 Sunday passengers in September 2014,[5] BART is the fifth-busiest heavy rail rapid transit system in the United States.

BART is operated by the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District, a special-purpose transit district that was formed in 1957 to cover San Francisco, Alameda County, and Contra Costa County. The acronym is almost universally pronounced "Bart," like the name, not spelled out.

BART combines the aesthetics and carrying capacity of a metro system with the logistics and pricing model of commuter rail. It is an alternative to highway transportation, especially to avoid congestion on the San Francisco Bay Bridge, which connects San Francisco to the East Bay suburbs and the city of Oakland. As of 2013, the BART system is being expanded to San Jose with the consecutive Warm Springs and Silicon Valley BART extensions.

History

Development and origins

Some of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System's current coverage area was once served by the electrified streetcar and suburban train system called the Key System. This early 20th-century system once had regular trans-bay traffic across the lower deck of the Bay Bridge. By the mid-1950s that system had been dismantled in favor of highway travel using automobiles and buses, given the explosive growth of expressway construction. A new rapid-transit system was proposed to take the place of the Key System during the late 1940s, and formal planning for it began in the 1950s.[6] Some funding was secured for the BART system in 1959,[7] and construction began a few years later. Passenger service began on September 11, 1972, initially just between MacArthur and Fremont.[8]

The new BART system was hailed by some authorities as a major step forward in subway technology,[9] though questions were asked concerning the safety of the system[10] and the huge expenditures necessary for the construction of the network.[11] All nine Bay Area counties were involved in the planning and envisioned to be connected by BART.

In addition to San Francisco, Alameda, and Contra Costa Counties, Santa Clara County, San Mateo County, and Marin County were initially intended to be part of the system. Santa Clara County Supervisors opted out in 1957, preferring instead to build expressways, and in 1961 San Mateo County supervisors voted to leave BART, saying their voters would be paying taxes to carry mainly Santa Clara County residents.[12] Although Marin County originally voted in favor of BART participation at the 88% level, the district-wide tax base was weakened by the withdrawal of San Mateo County. Marin County withdrew in early 1962 because its marginal tax base could not adequately absorb its share of BART's projected cost. Another important factor in Marin's withdrawal was an engineering controversy over the feasibility of running trains across the Golden Gate Bridge.[13]

The extension of BART into Marin was estimated to be as late as 30 years after the opening of the basic system. Initially, a lower level under the Golden Gate Bridge was the preferred route. In 1970 the Golden Gate Transportation Facilities Plan considered rapid transit links to Marin County via a tunnel under the Golden Gate[14] or a new bridge parallel to the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge[15] but neither of these plans was pursued.

Modernization

Since the mid-1990s, BART has been trying to modernize its system.[16] The fleet rehabilitation is part of this modernization; in 2009 fire alarms, fire sprinklers, yellow tactile platform edge domes, and cemented-mat rubber tiles were installed. The rough black tiles on the platform edge mark the location of the doorway of approaching trains, allowing passengers to wait at the right place to board. All faregates and ticket vending machines were replaced.

In late May 2007, BART stated its intention to improve non-peak (night and weekend) headways for each line to 15 minutes. The current 20-minute headways at these times is viewed as a psychological barrier to ridership.[17] In June 2007, BART temporarily reversed its position stating that the shortened wait times would likely not happen due to a $900,000 state revenue budget shortfall. Nevertheless, BART eventually confirmed the implementation of the plan by January 1, 2008.[18] Continued budgetary problems in 2009 caused BART to cancel the expanded non-peak service and return off-peak headways to 20 minutes on all lines in September 2009.[19]

In 2008 BART announced that it would install solar power systems on the roofs of its yards and maintenance facilities in Richmond and Hayward in addition to car ports with rooftop solar panels at its Orinda station.[20] The board lamented not being able to install them at all stations but it stated that Orinda was the only station with enough sun for them to make money from the project.[20]

In 2012 The California Transportation Commission announced they would provide funding for expanding BART facilities, through the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, in anticipation of the opening of the Silicon Valley Berryessa Extension. $50 million would go in part to improvements to the Hayward Maintenance Complex.[21]

Earthquake safety

A study dated September 14, 2010[22] shows that along with some Bay Area freeways, some of BART's overhead structures could be extensively damaged and potentially collapse in the event of a major earthquake, which is highly likely to happen in the Bay Area within the next thirty years.[23] Extensive seismic retrofit will be necessary to address many of these deficiencies, although one in particular, the penetration of the Hayward Fault Zone by the Berkeley Hills Tunnel, will be left for correction after any disabling earthquake. After the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, BART Transbay Tube rail service was closed until 9:30PM, less than 5 hours after the quake, when partial service was restored. Full service began again at 5am the next day and the trains ran continuously, 24 hours a day, until December 3, 1989, to compensate for the closure of the Bay Bridge, which was damaged by the earthquake.[24][25]

Instituted in August 2012, an earthquake early warning system was created with the help of UC Berkeley seismologists who hooked BART into data flowing from the more than 200 stations of the California Integrated Seismic Network throughout Northern California. Electronic signals from seismic stations travel much faster than seismic waves. For quakes outside the Bay Area, these data give BART’s central computers advance notice that shaking is on the way; for quakes in the Bay Area, it provides more rapid warning. If the messages from the seismic network indicate ground motion above a certain threshold, the central computers which supervise train performance will institute what BART calls “service” braking, which is a normal slowdown to 26 miles per hour (42 km/h) from speeds up to 70 miles per hour (110 km/h).

“The earthquake early warning system will enable BART to stop trains before earthquake shaking starts and thereby prevent derailment, and save passengers from potential injuries”, said BART Board President John McPartland. “We are the first transit agency in the United States to provide this early warning and intervention.” “This is a key step forward in our development of an early warning system for the U.S.”, said Richard Allen, director of the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory and a UC Berkeley professor of earth and planetary science. “There are several groups now receiving alerts from our demonstration earthquake alert system, but BART is the first to implement an automated response to earthquake alerts. We hope that others will follow BART’s lead.” [26]

The 3.6 miles (5.8 km) Transbay Tube has also required earthquake retrofitting, both on its exterior and interior. The tube lies in a shallow trench dredged on the bottom of San Francisco Bay, and was anchored to the bottom by packing around the sides and top with mud and gravel. Recent earthquake research has shown that this fill may be prone to soil liquefaction during an earthquake, which could allow the buoyant hollow tube to break loose from its anchorages. Retrofitting work required the fill to be compacted, to make it denser and less prone to liquefaction. On the interior of the tube, BART began a major retrofitting initiative in March 2013, which involved installing heavy steel plates at various locations inside the tube that most needed strengthening, to protect them from sideways movement in an earthquake. In order to complete this work between March 2013 and December 2013, BART closed one of the two bores of the tube early on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday nights; trains shared a single tunnel between Embarcadero and West Oakland after 10 pm on those evenings, causing travel delays of 15 to 20 minutes.[27] The work, estimated to last approximately 14 months, was completed after only 8 months of construction.[28]

Plans

As BART celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2013, management announced their plans for the next 40 years. This includes adding a new four-bore Transbay Tube beneath San Francisco Bay that would run parallel and south of the existing tunnel and emerge at the Transbay Transit Terminal to provide connecting service to Caltrain and the future California High Speed Rail system. The four-bore tunnel would provide two tunnels for BART and two tunnels for conventional/high-speed rail. The BART system and conventional US rail use different and incompatible rail gauges and different loading gauges.[3]

BART's plan focus is on improving service and reliability in its core system (where density and ridership is highest), rather than extensions into far-flung suburbia. These plans include: a line that would continue from the Transbay Terminal through the South-of-Market, northwards on Van Ness and terminating in western San Francisco along the Geary corridor, the Presidio, or North Beach; a line along the Interstate Highway 680 corridor; and a fourth set of rail tracks through Oakland.[29] However, BART maps still tout planned extensions to Livermore and (via diesel multiple unit eBART service) Antioch, in the fringes of Alameda and Contra Costa Counties.

Current system

BART revenue routes cover 104 miles (167 km) with 44 stations.[3] Trains run on exclusive right-of-way, in subways or elevated; they are powered by electricity delivered by a powered "third rail". The system uses a 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) Indian gauge[3] and mostly ballastless track instead of the 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge and railroad ties used on United States railroads. So all maintenance and support equipment must be custom built.

BART control allows a maximum speed of 76–80 miles per hour (122–129 km/h),[3] but since 1976 the usual limit has been 66–70 miles per hour (106–113 km/h) because the single disc per axle vital brake system will fail when making an all friction stop from 80 miles per hour (130 km/h) with a fully loaded car. Dynamometer simulations showed this before the system opened, and another disc on each axle was recommended, but BART believed such a failure of the non-vital dynamic brake system would be rare. Unfortunately the failure mode of the dynamic brake is to "OFF", and such failures happen fairly often as the result of minor glitches.

Trains have from three cars to a maximum of ten, which fills the 700 feet (213 m) length of a platform.[30] At its maximum length of 710 feet (216 m), BART has the longest trains of any metro system in the United States. The system also features car widths of 10.5 feet (3.2 m) (the same width as a Budd Metroliner), a maximum gradient of four percent, and a minimum curve radius of 394 feet (120 m) on the main lines .[31]

Electric current is delivered to the trains over a third rail.[4] In stations the third rail is on the side away from the passenger platform, except the middle platform at the San Francisco International Airport station. This reduces the danger of a passenger falling on the third rail or stepping on it to climb back to the platform after falling off. On ground-level tracks, the third rail alternates from one side of the track to the other, providing breaks in the third rail to allow for emergency evacuations.

Underground tunnels, aerial structures and the Transbay Tube have evacuation walkways and passageways to allow for train evacuation without exposing passengers to contact with the third rail, which is located as far away from these walkways as possible.[32] The voltage on the steel third rail is 1000 volts DC.

Many of the original system 1970s-era BART stations, especially the aerial stations, feature simple, Brutalist architecture, while the newer stations are a mix of Neomodern and Postmodern architecture.

Ridership levels

| Average Weekday Ridership | ||

|---|---|---|

| FY* | Ridership | %± |

| 1973 | 32,000 | — |

| 1974 | 57,400 | +74.9% |

| 1975 | 118,003 | +105.6% |

| 1976 | 131,000 | +11.0% |

| 1977 | 133,453 | +1.9% |

| 1978 | 146,780 | +10.0% |

| 1979 | 151,712 | +3.4% |

| 1980 | 148,682 | −2.0% |

| 1981 | 161,965 | +8.9% |

| 1982 | 184,062 | +13.6% |

| 1983 | 186,293 | +1.2% |

| 1984 | 202,536 | +8.7% |

| 1985 | 211,612 | +4.5% |

| 1986 | 204,244 | −3.5% |

| 1987 | 194,226 | −4.9% |

| 1988 | 198,259 | +2.1% |

| 1989 | 207,231 | +4.5% |

| 1990 | 241,525 | +16.5% |

| 1991 | 247,456 | +2.5% |

| 1992 | 249,548 | +0.8% |

| 1993 | 253,838 | +1.7% |

| 1994 | 251,981 | −0.7% |

| 1995 | 248,169 | −1.5% |

| 1996 | 248,669 | +0.2% |

| 1997 | 260,543 | +4.8% |

| 1998 | 265,324 | +1.8% |

| 1999 | 278,683 | +5.0% |

| 2000 | 310,268 | +11.3% |

| 2001 | 331,586 | +6.9% |

| 2002 | 310,725 | −6.3% |

| 2003 | 295,158 | −5.0% |

| 2004 | 306,570 | +3.9% |

| 2005 | 310,717 | +1.4% |

| 2006 | 322,965 | +3.9% |

| 2007 | 339,359 | +5.1% |

| 2008 | 357,775 | +5.4% |

| 2009 | 356,712 | −0.3% |

| 2010 | 334,984 | −6.1% |

| 2011 | 345,256 | +3.1% |

| 2012 | 366,565 | +6.2% |

| 2013 | 392,293 | +7.0% |

| 2014 | 399,145 | +1.7% |

| Sources:[2][33] | ||

During the fiscal year ending June 30, 2014, BART recorded an average weekday ridership of 399,145, the highest in its history,[2] making BART the fifth-busiest heavy rail rapid transit system in the United States. During fiscal year 2013, the busiest station was Embarcadero with 41,059 average weekday exits, followed by Montgomery Street with 39,167. The busiest station outside of San Francisco was Downtown Berkeley with 13,131 riders, followed by 12th Street Oakland City Center with 12,979. The least busy station was North Concord / Martinez with 2,499 weekday exits.[34]

| Ridership records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date | Ridership | Remarks |

| October 31, 2012 | 568,061 | Giants' victory parade |

| November 3, 2010 | 522,198 | Giants' victory parade |

| August 29, 2013 | 475,015 | Bay Bridge closure |

| August 30, 2013 | 457,018 | Bay Bridge closure |

| October 29, 2009 | 442,067 | Bay Bridge closure |

| October 30, 2009 | 437,693 | Bay Bridge closure |

BART's one-day ridership record was set on Wednesday, October 31, 2012 with over 568,061 passengers attending the San Francisco Giants' victory parade for their World Series championship.[35] This surpassed the record set two years earlier of 522,198 riders on Wednesday, November 3, 2010 for the Giants' 2010 World Series victory parade.[36] Before that, the record was 442,100 riders on Thursday, October 29, 2009, following an emergency closure of the Bay Bridge.[37] During a planned closure of the Bay Bridge, there were 475,015 riders on Thursday, August 29, 2013, making that the number 3 ridership record.[38]

BART set a Saturday record of 319,484 riders on October 6, 2012, coinciding with several sporting events and Fleet Week.[39] BART set a Sunday ridership record of 292,957 riders on June 30, 2013, which mainly coincided with the San Francisco Gay Pride Parade,[40] surpassing the previous Sunday ridership when the Pride Parade was held.[40]

High automotive fuel prices helped to push BART ridership to record levels during much of 2012. Prior to 2013, five of BART's top ten ridership days of all time occurred in September and October 2012.[41][42]

Routes

All routes pass through Oakland, and all but the Richmond–Fremont route pass through the Transbay Tube into San Francisco and beyond to Daly City. Most segments of the BART system carry trains of more than one route.

Trains regularly operate on five routes. Unlike most other rapid transit and rail systems around the world, BART lines are generally not referred to by shorthand designations. Although the lines have been colored consistently on BART system maps since inception, they are only occasionally referred to officially by color names.[43] However, future train cars will display line colors more prominently.[44]

The five BART lines are generally identified on maps, schedules, and signage by the names of their termini:

- Richmond–Fremont: Follows a former Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway right-of-way from Richmond to Berkeley, and a former Western Pacific Railroad right-of-way from Oakland to Fremont. Operates daily.

- Pittsburg/Bay Point–SFO/Millbrae: Follows SR 4, a former Sacramento Northern Railway right-of way, and SR 24 from Pittsburg to Oakland, and extends beyond Daly City to San Francisco International Airport. This is the longest point-to-point line in the BART system. Operates daily, with the line extending from the airport to Millbrae on weeknights and weekends.

- Fremont–Daly City: Coincides with the Richmond-Fremont line from Fremont to Oakland. Operates until early evening Mondays through Saturdays.

- Richmond–Daly City/Millbrae: Coincides with the Richmond-Fremont line from Richmond to Oakland, and extends beyond Daly City to Millbrae following a former Southern Pacific Railroad right-of-way, which is also served by Caltrain beyond San Bruno. Operates until early evening Mondays through Saturdays, with the line terminating at Daly City on Saturdays.

- Dublin/Pleasanton–Daly City: Follows Interstate 580 via Castro Valley to San Leandro, where it coincides with the Fremont-Daly City line. Operates daily.

In addition BART also operates a separate automated guideway transit line:

- Coliseum–Oakland Int'l Airport: Travels along Hegenberger Road from the Oakland International Airport to the BART system at Coliseum station. Operates daily.

Hours of operation

BART has five lines; most of each line's length is on track shared with other lines. Trains on each line run every fifteen minutes on weekdays and twenty minutes during evenings, weekends and holidays; some stations in Oakland and San Francisco are on four lines and therefore see 16 trains an hour on each track.

BART service begins around 4:00am on weekdays, 6:00am on Saturdays, and 8:00am on Sundays. Service ends every day near midnight with station closings timed to the last train at station. Two of the five lines, the Fremont–Daly City and Richmond–Daly City/Millbrae lines, do not have night (after 7:00pm & 8:00pm, respectively) or Sunday service, but all stations remain accessible by transfer from the other lines.[45][46][47]

All Nighter bus service runs when BART is closed. Thirty out of forty-four BART stations are served either directly or within a few blocks. BART tickets are not accepted on these buses, with the exception of BART Plus tickets (which are no longer accepted on AC Transit, Muni, SamTrans, or VTA beginning in 2013), and each of the four bus systems that provide All-Nighter service charges its own fare, which can be up to $3.50; a four-system ride could cost as much as $9.50 as of 2007.[48]

Fares

Fares on BART are comparable to those of commuter rail systems and are higher than those of most subways, especially for long trips. The fare is based on a formula that takes into account both the length and speed of the trip. A surcharge is added for trips traveling through the Transbay Tube, and/or through San Mateo County (which access to includes San Francisco International Airport), which is not a BART member. Passengers can use refillable paper-plastic-composite tickets,[49] on which fares are stored via a magnetic strip, to enter and exit the system. The exit faregate prints the remaining balance on the ticket each time the passenger exits the station. A paper ticket can be refilled at a ticket machine, the remaining balance on any ticket can be applied towards the purchase of a new one, or a card is captured by the exit gate when the balance reaches zero; multiple low value cards can be combined to create a larger value card but only at specific ticket exchange locations, located at some BART stations.[50]

BART relies on unused ticket values, particularly of patrons discarding low-value cards, as an additional source of revenue, estimated by some to be as high as $9.9 million.[51] The paper ticket technology is identical to the Washington Metro's paper fare card, though the BART system does not charge higher fares during rush hour. Both systems were supplied by Cubic Transportation Systems, with contract for BART being awarded in 1974.

Clipper, a contactless smart card accepted on all major Bay Area public transit agencies, may be used in lieu of a paper ticket.

The BART minimum fare of $1.85 is charged for trips (except San Mateo County trips) under 6 miles (9.7 km).[52] The maximum one-way fare including all possible surcharges is $15.40, the journey between San Francisco International Airport and Oakland International Airport. The farthest possible trip, from Pittsburg/Bay Point to Millbrae, costs less because of the $4 additional charge added to SFO trips and $6 additional charge added to OAK trips.[53] Passengers without sufficient fare to complete their journey must use a cash-only AddFare machine to pay the remaining balance in order to exit the station.

BART uses a system of five different color-coded tickets for regular fare, special fare, and discount fare to select groups as follows:[54]

- Blue tickets – General: the most common type

- Red tickets – Disabled Persons and children aged 4 to 12: 62.5% discount, special ID required (children under the age of 4 ride free)

- Green tickets – Seniors age 65 or over: 62.5% discount, proof of age required for purchase

- Orange tickets – Student: special, restricted-use 50% discount ticket for students age 13–18 currently enrolled in high or middle school

- BART Plus – special high-value ticket with 'flash-pass' privileges with regional transit agencies. Effective Jan. 1, 2013, the SFMTA (Muni), as well as SamTrans and VTA, no longer participate in the BART Plus Program. AC Transit stopped participating in the BART Plus program in 2003. The trend seems to be that the BART Plus ticket is being phased-out in favor of the Clipper system, as the only Bay Area transit agencies that still participate in the BART Plus program do not yet accept Clipper cards.

Unlike many other rapid transit systems, BART does not have an unlimited ride pass, and the only discount provided to the public is a 6.25% discount when "high value tickets" are purchased with fare values of $48.00 and $64.00, for prices of $45.00 and $60.00 respectively. Amtrak's Capitol Corridor and San Joaquins trains sell $10.00 BART tickets on board in the café cars for only $8.00,[55][56] resulting in a 20% discount. A 62.5% discount is provided to seniors, the disabled, and children age 5 to 12. Middle and high school students 13 to 18 may obtain a 50% discount if their school participates in the BART program; these tickets are intended to be used only between the students' home station and the school's station and for transportation to and from school events. The tickets can be used only on weekdays. These School Tickets and BART Plus tickets have a last-ride bonus where if the remaining value is greater than $0.05, the ticket can be used one last time for a trip of any distance. Most special discounted tickets must be purchased at selected vendors and not at ticket machines. The Bart Plus tickets can be purchased at the ticket machines.

The San Francisco Muni "A" monthly pass provides unlimited rides within San Francisco, with no fare credit applied for trips outside of the City. San Francisco pays $1.02 for each trip taken under this arrangement.[57]

Fares are enforced by the station agent, who monitors activity at the fare gates adjacent to the window and at other fare gates through closed circuit television and faregate status screens located in the agent's booth. All stations are staffed with at least one agent at all times.

Proposals to simplify the fare structure abound. A flat fare that disregards distance has been proposed by BART director Joel Keller. The lesser extreme involves the implementation of a simplified structure that would create fare bands or zones. The implementation of either scheme would demote the use of distance-based fares and shift the fare-box recovery burden to the urban riders in San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley and away from the suburban riders of East Contra Costa, Southern Alameda, and San Mateo Counties, where density is lowest, and consequently, operational cost is highest.[58]

Facilities

Cell phone and Wi-Fi

In May 2004, BART became the first transit system in the United States to offer cellular telephone communication to passengers of all major wireless carriers on its trains underground.[59] Service was made available for customers of Verizon Wireless, Sprint/Nextel, AT&T Mobility, and T-Mobile in and between the four San Francisco Market Street stations from Civic Center to Embarcadero. In December 2009, service was expanded to include the Transbay Tube, thus providing continuous cellular coverage between West Oakland and Balboa Park.[60] In August 2010, service was expanded to all underground stations in Oakland (19th Street, 12th Street/Oakland City Center, and Lake Merritt).[61] The eventual goal is to provide uninterrupted cellular coverage of the entire BART system. As of November 2012 passengers in both the Berkeley Hills tunnel and the Berkeley subway (Ashby, Downtown and North Berkeley) have cell service. The only section still not covered by cell service is a short tunnel that leads to Walnut Creek BART, and all the San Mateo subway stations (including service to SFO and Millbrae).

Starting February 20, 2007, BART entered into an agreement to permit a beta test of Wi-Fi Internet access for travelers. It initially included the four San Francisco downtown stations: Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell, and Civic Center. The testing and demonstration also included above ground testing to trains at BART's Hayward Test Track. The testing and deployment was extended into the underground interconnecting tubes between the four downtown stations and further. The successful demonstration and testing provided for a ten-year contract with WiFi Rail, Inc. for the services throughout the BART right of way.[62] In 2008 the Wi-Fi service was expanded to include the Transbay Tube.[63]

In 2011 during the Charles Hill killing and aftermath BART attracted controversy by disabling cell phone service on the network to hamper demonstrators.[64]

Library-a-Go-Go

Since 2008 the district has been adding Library-a-Go-Go vending machines that give out books.[65] The Contra Costa County Library machine was added to the Pittsburg/Bay Point station in 2008.[65] The $100,000 machine, imported from Sweden, was the first in the nation and was followed by one at the El Cerrito del Norte station in 2009.[65][66][67] Later in 2011 a Peninsula Library System machine was added at the Millbrae Station.[65][68]

Connecting services

BART has direct connections to two regional rail services: Caltrain, which provides service between San Francisco, San Jose, and Gilroy, at the Millbrae Station, and Amtrak's Capitol Corridor, which runs from Sacramento to San Jose, at the Richmond and Coliseum/Oakland Airport stations.

In addition, BART has connection to the Altamont Commuter Express commuter rail service via shuttle at the Fremont, Dublin/Pleasanton and West Dublin/Pleasanton stations.

BART connects to San Francisco's local light rail system, the Muni Metro. The upper track level of BART's Market Street subway, which in plans from 1960 would have carried BART trains to the Twin Peaks Tunnel,[69] was turned over to Muni and both agencies share the Embarcadero, Montgomery Street, Powell and Civic Center stations. Some Muni Metro lines connect with (or pass nearby) the BART system at the Balboa Park and Glen Park stations.

Connecting services via bus

A number of bus transit services connect to BART, which, while managed by separate agencies, are integral to the successful functioning of the system. The primary providers include the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni), AC Transit, SamTrans, County Connection, and the Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District (Golden Gate Transit). Until 1997, BART ran its own "BART Express" connector buses,[70] which ran to eastern Alameda County and far eastern and western areas of Contra Costa County; these routes were later devolved to sub-regional transit agencies such as Tri Delta Transit and the Livermore Amador Valley Transit Authority (WHEELS) or, in the case of Dublin/Pleasanton service, replaced by a full BART extension.

Other services connect to BART including the Emery Go Round (Emeryville), WestCAT (north-western Contra Costa County), San Leandro LINKS, Napa VINE, Rio Vista Delta Breeze, Dumbarton Express, SolTrans, Union City Transit, and the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority in Silicon Valley.

Several commuter and interregional bus services connect to BART including the San Joaquin RTD Commuter (Stockton), Tri Delta Transit (Contra Costa County), Greyhound, California Shuttle Bus, Valley of the Moon Commute Club, Amtrak Thruway Motorcoach, and Modesto Area Express BART Express.

Cars

BART hosts car sharing locations at many stations, a program pioneered by City CarShare. Riders can transfer from BART and complete their journeys by car. BART offers long-term airport parking through a third-party vendor[71] at most East Bay stations. Travelers must make an on-line reservation in advance and pay the daily fee of $5 before they can leave their cars at the BART parking lot. Many BART stations offer parking.[72]

Airports

BART connects directly to the San Francisco International Airport; connections are available to AirTrain for those not departing or arriving from the international terminal.

The Coliseum–Oakland International Airport line, or BART to OAK Airport, is an automated guideway transit line that directly connects BART and Amtrak at the Coliseum station to the terminal buildings at Oakland International Airport. Federal and state funding for the OAC was authorized in September 2010, and the groundbreaking was held October 20.[73][74] Construction of the $484 million project took approximately four years to complete.[75] It opened on November 22, 2014,[75] replacing the AirBART bus line. Unlike the previous AirTrain buses, the BART to OAK system is operated by BART, and is integrated into the BART fare system with standard BART ticket gates located at the entrance of the Airport end of the people mover. The connector's automated guideway transit (AGTs) vehicles are cable-propelled and operate on a fixed, elevated guideway 3.2 miles (5.1 km) long. The AGTs arrive at the Coliseum BART station every 5 minutes during the day[76] and are designed to transport travelers to the airport in about eight minutes[75] with an on-time performance of more than 99 percent. Initially there are four three-car trains (113 passengers each) but the system is designed to allow for expansion to four four-car trains (148 passengers each).[77]

Organization and management

| 2012 statistics | |

|---|---|

| Number of vehicles | 670 |

| Initial system cost | $1.6 billion |

| Equivalent cost in 2004 dollars (replacement cost) | $15 billion |

| Hourly passenger capacity | 15,000 |

| Maximum daily capacity | 360,000 |

| Average weekday ridership | 365,510 |

| Annual operating revenue | $379.10 million |

| Annual expenses | $619.10 million |

| Annual profits (losses) | ($240.00 million) |

| Rail cost/passenger mile (excluding capital costs) | $0.332 |

Governance

The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District is a special governmental agency created by the State of California consisting of Alameda County, Contra Costa County, and the City and County of San Francisco. San Mateo County, which hosts six BART stations, is not part of the BART District. It is governed by an elected Board of Directors with each of the nine directors representing a specific geographic area within the BART district. BART has its own police force.[78]

While the district includes all of the cities and communities in its jurisdiction, some of these cities do not have stations on the BART system. This has caused tensions among property owners in cities like Livermore who pay BART taxes but must travel outside the city to receive BART service.[79] In areas like Fremont, the majority of commuters do not commute in the direction that BART would take them (many Fremonters commute to San Jose, where there is currently no BART service). This would be alleviated with the completion of a BART-to-San Jose extension project and the opening of the Berryessa Station in San Jose.

Budget

In 2005, BART required nearly $300 million in funds after fares. About 37% of the costs went to maintenance, 29% to actual transportation operations, 24% to general administration, 8% to police services, and 4% to construction and engineering. In 2005, 53% of the budget was derived from fares, 32% from taxes, and 15% from other sources, including advertising, station retail space leasing, and parking fees.[80] BART's 2012 farebox recovery ratio of 68.2%[81] is relatively high for a U.S. public transit agency operating over such long distances with high frequency. BART "train operators and station agents have a maximum annual salary of $62,000 with an average of $17,000 a year in overtime pay".[82] (For its part, BART management claims that in as of 2013, union train operators and station agents average about $71,000 in base salary and $11,000 in overtime annually, and also pay a $92 monthly fee for health insurance.)[83]

Rolling stock

Car types

BART operates four types of cars, built from three separate orders, totaling 669 cars.

To run a typical peak morning commute, BART requires 579 cars. Of those, 541 are scheduled to be in active service; the other 38 are used to build up four spare trains (essential for maintaining on-time service). At any one time, the remaining 90 cars are in for repair, maintenance, or some type of planned modification work.[84]

The A and B cars were built from 1968 to 1971 by Rohr Industries, an aerospace manufacturing company that had recently started mass-transit equipment manufacturing. The A cars were designed as leading or trailing cars only, with an aerodynamic fiberglass operator's cab housing train control equipment and BART's two-way communication system, and extending 5 feet (1.52 m) longer than the B- and C-cars. A and B cars can seat 60 passengers comfortably, and under crush load, carry over 200 passengers. B cars have no operator's cab and are used in the middle of trains to carry passengers only. Currently, BART operates 59 A cars and 389 B cars.[4][85] The BART A cars have a larger cab window than the C cars, allowing riders to look out of the front or the back of the train.

The C cars feature a fiberglass operator's cab and control and communications equipment like the A cars, but do not have the aerodynamic nose, allowing them to be used as middle cars as well. This allows faster train-size changes without having to move the train to a switching yard. C cars can seat 56 passengers and under crush load accommodate over 200 passengers. The first C cars, referred to as C1 cars, were built by Alstom between 1987 and 1989.[86] The second order of C cars, built by Morrison-Knudsen (now Washington Group International), are known as C2 cars. The C2 cars were identical to the C1 cars but featured an interior with a blue/gray motif. At the time of their construction, the C2 cars also featured flip-up seats which could be folded to accommodate wheelchair users; these seats were later removed during refurbishment. Currently, BART operates 150 C1 cars and 80 C2 cars. The "C" cars have a bright white segment as the final approximately two feet (61 cm) of the car at their cab end.

Refurbishments

Prior to the introduction of the C2 cars, the seats and carpeted flooring in all the cars were brown. In 1995, BART contracted with ADtranz (acquired by Bombardier Transportation in 2001) to refurbish and overhaul the 439 original Rohr A- and B-cars, updating the old brown fabric seats to the less-toxic and easier-to-clean,[6] light-blue polyurethane seats in use today and bringing the older cars to the same level of interior amenities as the C2 fleet. The project was completed in 2002. The A, B, and C cars were all given 3-digit numbers originally, but when refurbished 1000 was added to the number of each individual A/B car (e.g. car 633 would become 1633). The C2 cars are numbered in the 2500 series; the C/C1 cars still have 3-digit numbers.

Because one of the original design goals was for all BART riders to be seated, the older cars had fewer provisions such as grab bars for standing passengers. In the late 2000s BART began modifying some of the C2 cars to test features such as hand-straps and additional areas for luggage, wheelchairs and bicycles. These new features were later added to the A, B, and C1 cars.

All BART cars feature upholstered seats. It was reported in March 2011 that several strains of molds and bacteria were found on fabric seats on BART trains, even after wiping with antiseptic. These included bacteria from fecal contamination.[87] In April, BART announced it would spend $2 million in the next year to replace the dirty seats.[88] The new seats would feature vinyl-covered upholstery which would be easier to clean.[89] The transition to the new seats was completed in December 2014.[90]

Originally all the cars had carpeted flooring. Due to similar concerns regarding cleanliness, the carpeting in most of the cars has been removed. Most of the A and B, and C2 cars now feature vinyl flooring in either grey or blue coloring, while most of the C1 cars feature a spray-on composite flooring. A few cars still feature carpeting, as their carpets have not yet been replaced.[90]

Traction motors

Prior to rebuilding,[91] the Direct Current (DC) traction motors used on the 439 Rohr BART cars were model 1463 with chopper controls from Westinghouse, who also built the automatic train control system for BART. The Rohr cars were rebuilt with ADtranz model 1507C 3-phase alternating current (AC) traction motors with insulated-gate bipolar transistor (IGBT) inverters. The Westinghouse motors are still in use on the Alstom C (C1) and Morrison-Knudsen C2 cars and the motors that were removed from the Rohr cars were retained as spare motors for use on them. The HVAC system on the Rohr BART cars before rehabilitation were built by Thermo King, when it was a subsidiary of Westinghouse; it is now a subsidiary of Ingersoll Rand. The current HVAC systems on the rebuilt Rohr-built Gen 1 cars were built by Westcode and possibly also AdTranz who had subcontracted the HVAC system to Westcode.[92]

Noise

Many BART passengers have noted that the system is noisy, often exceeding 100 decibels, especially in the Transbay Tube between San Francisco and Oakland, but in other places as well. However, then-chief BART spokesperson Linton Johnson has stated that BART averages 70 – 80 dB, below the danger zone, and according to a 1997 study by the National Academy of Sciences, BART ranks as among the quietest transit systems in the nation. Critics have countered that this study analyzed straight, above-ground portions at 30 mph (48 km/h) of different systems throughout the country which may not be representative of actual operating conditions (much of BART is under ground, curvy - even in the Transbay Tube, and has much faster peak operating speeds than many other systems in the nation). [93]

Train noise on curves is caused by the wheels of the rolling stock damaging the surface of the track, causing "corrugation". The process by which this occurs is as follows:

- A pair of wheels attached to one another directly with an axle go through a turn with the same rotations per minute. As a result, the wheel on the inside track must slip to make up for the difference in the length of the track.

- This slippage causes the wheel to wear and become uneven.

- This unevenness of the wheel creates corrugation, not only on the track in the curve, but elsewhere in the system as well.

The corrugation of the rails must be continuously ground away to remedy this situation. However, maintenance costs money, and deferred maintenance as a result of tight budgets results in increasing noise levels.

Many trains with wheels directly connected to each other through an axle have this problem, but it can be partially mitigated by use of canted wheels, allowing, in effect, variable wheel diameter to compensate for differing track lengths during turns. BART rolling stock has flat wheels, causing slippage and the resulting noise from the increased corrugation. New rolling stock with flat wheels rotating at a variable rate in turns instead of being directly connected via the axle, along with a final re-grinding of the track to ensure that it is no longer pitted, would greatly reduce noise levels.

Additional noise comes from the traction motors. On the ADtranz motors currently in use on the A and B cars, a whining noise comes from the high speed electronic inverters.[94] The original Westinghouse motors, still in use on the C1 and C2 cars, make a distinctive buzzing sound; the buzzing sound comes from the motor reactors.[95]

Future railcars

To speed up rider entry and exit at stations, BART is preparing to introduce new 6-door cars. BART received proposals from five suppliers, and on May 10, 2012 awarded a $896.3 million contract to Canadian railcar manufacturer Bombardier Transportation with an order for 410 new cars, split into a base order of 260 cars and a first option order of 150 additional cars.[96][97] On November 21, 2013, BART purchased 365 more cars, for a total fleet size of 775 new railcars, while also accelerating the delivery schedule by 21 months (from 10 cars per month up to 16 cars per month) and lowering procurement costs by approximately $135 million.[98][99] According to the contract, at least two-thirds of the contract’s amount must be spent on American parts.

There will be two different types of car configurations for the new fleet; a cab car (D-cars), which will make up 40% of the fleet, or, 310 cars, and a non-cab car (E-cars), which will make up the remainder of the fleet, or, 465 cars.[99][100] All cars are to be equipped with bike racks, new vinyl seats (57 per car), and a brand new passenger information system which will display next stop information.[101]

The 10-car test pilot train is to be delivered to BART in 2015, where it will undergo an 18-month testing period. Due to potential access issues for people with disabilities, the pilot car layout was modified by the BART board in February 2015 to include two wheelchair spaces in the center of the car, as well as alternative layouts for bike and flexible open spaces.[102] Upon approval, delivery of the production cars is set to begin January 2017, with the first 140 cars expected to be in service by the end of the same year. Delivery of all 775 cars is expected to be completed by September 2021.[103]

Comparison with other rail transit systems

BART, like other transit systems of the same era, endeavored to connect outlying suburbs with job centers in Oakland and San Francisco by building lines that paralleled established commuting routes of the region's freeway system.[104] The majority of BART's service area, as measured by percentage of system length, consists of low-density suburbs. Unlike the Chicago "L" or the London Underground, individual BART lines were not designed to provide frequent local service, as evidenced by the system's current maximum achievable headway of 13.33 minutes per line through the quadruple interlined section in San Francisco. Within San Francisco city limits, Muni provides local light-rail and subway service, and runs with smaller headways (and therefore provides more frequent service) than BART.

BART could be characterized as a "commuter subway," since it has many characteristics of a regional commuter rail service, such as lengthy lines that extend to the far reaches of suburbia, with significant distances between stations.[105][106] BART also possesses some of the qualities of a metro system[107] in the urban areas of San Francisco and downtown Oakland; where multiple lines converge, it takes on the characteristics of an urban metro, including short headways and transfer opportunities to other lines. Urban stations are as close as one-half mile (800 m) apart, and have combined 2½ to 5-minute service intervals at peak times.

Within the United States, BART is very similar in character to the Washington Metro, which opened 4 years after BART and likewise features outdoor, suburban stations in addition to underground, closely spaced urban stations, with the latter receiving more frequent service than the former. Like BART, the Washington Metro's fares are based on the distance traveled, and the system also uses similar magnetic stripe paper farecards that riders insert into faregates at entry and exit. In many ways, BART resembles the S-Bahn train systems of numerous German cities, or the Paris RER system. Like those networks, BART has a number of mostly-underground stations in the center of an urban core and runs service out to suburban areas following a specific schedule.

Future expansion and extension

Expansion projects for the Bay Area Rapid Transit have existed ever since the opening of the project. Expansion projects currently under construction, or in planning, include the Warm Springs extension,[108] the San Jose extension, eBART, the Livermore extension, and 'wBART': I-80/West Contra Costa Corridor (extension to Hercules); in addition, at least four infill stations are planned along existing routes.[109] Previously completed projects include the extensions to Colma and Pittsburg/Bay Point (1996), Dublin/Pleasanton (1997), SFO/Milbrae (2003),[110] and the automated guideway transit spur line that connects BART to Oakland International Airport (2014).[75]

On the Fremont line the Warm Springs extension is being built. It will be a precursor to Phase I of the San Jose extension that will begin construction in mid-2012, with stations at Milpitas and Berryessa.[111][112] Heading east from Pittsburg/Bay Point, two additional stations are under construction and will be added to the system using a diesel multiple unit "eBART" train system with stations at Pittsburg and Antioch.[113]

BART Silicon Valley extension

This segment will extend past the current Warm Springs project in two phases. The first phase is known as the Berryessa Extension, which commences at the south end of the Warm Springs Extension and extends southeastward across the Alameda-Santa Clara county line for ten miles toward eastern downtown San Jose with stops at Irvington, Milpitas and possibly Calaveras. The segment will terminate at Berryessa Station in San Jose. Construction of the second segment (downtown San Jose to Santa Clara) will be delayed pending future funding for the more expensive underground segment. Once funding has been secured, the BART line will extend southwest for roughly three miles, then turning near SAP Center at a Diridon/Arena station to the northwest. The ultimate terminus will be Santa Clara station.

Incidents

Automatic Train Control failure

In the 1970s, three BART engineers developed concerns about the safety of the Automatic Train Control system, but were unable to get their supervisors to consider them. Together, they went to the BART Board of Directors. An investigation started, and the BART management retaliated by firing the engineers. Investigation into the ATC and related design and management issues was still underway when, on October 2, 1972, a BART train overran a station due to ATC failure and injured several passengers. During the litigation process, the IEEE filed an amicus curiae brief in support of the engineers, and in 1978 the IEEE recognized the engineers with an ethics award.[114] The "BART case" is now widely used in courses on engineering ethics.

Fatal electrical fire

In January 1979, an electrical fire occurred on a train as it was passing through the Transbay Tube. One firefighter (Lt. William Elliott, 50, of the Oakland Fire Department) was killed in the effort to extinguish the blaze. Since then, safety regulations have been updated.[115]

Death of worker James Strickland

On October 14, 2008, track inspector James Strickland was struck and killed by a train as he was walking along a section of track between the Concord and Pleasant Hill stations. Strickland's death started an investigation into BART's safety alert procedures.[116] At the time of the accident, BART had assigned trains headed in opposite directions to a shared track for routine maintenance. BART came under further fire in February 2009 for allegedly delaying payment of death benefits to Strickland's family.[117]

BART Police shooting of Oscar Grant III

On January 1, 2009, a BART Police officer, Johannes Mehserle, fatally shot Oscar Grant III.[118][119]

Eyewitnesses gathered direct evidence of the shooting with video cameras, which were later submitted to and disseminated by media outlets and watched hundreds of thousands of times[120] in the days following the shooting. Violent demonstrations occurred protesting the shooting.[121]

Mehserle was arrested and charged with murder, to which he pleaded not guilty. Oakland civil rights attorney John Burris filed a US$25 million wrongful death claim against the district on behalf of Grant's daughter and girlfriend.[122] Oscar Grant III's father also filed a lawsuit claiming that the death of his son deprived him of his son's companionship.

Mehserle's trial was subsequently moved to Los Angeles following concerns that he would be unable to get a fair trial in Alameda County. On July 8, 2010, Mehserle was found guilty on a lesser charge of involuntary manslaughter.[123] He was released on June 13, 2011 and is now on parole.[124]

Charles Hill killing and aftermath

On July 3, 2011, two officers of the BART Police shot and killed Charles Hill at Civic Center Station in San Francisco. Hill was allegedly carrying a knife.[125]

On August 12, 2011, BART shut down cellphone services on the network for three hours in an effort to hamper possible protests against the shooting[126][127] and to keep communications away from protesters at the Civic Center station in San Francisco.[128] The shutdown caught the attention of Leland Yee and international media, as well as drawing comparisons to the former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak in several articles and comments.[129] Antonette Bryant, the union president for BART, added that, "BART have lost our confidence and are putting rider and employee safety at risk."[130]

Members of Anonymous broke into BART's website and posted names, phone numbers, addresses, and e-mail information on the Anonymous website.[131][132]

On August 15, 2011, there was more disruption in service at BART stations in downtown San Francisco.[133][134][135] The San Francisco Examiner reported that the protests were a result of the shootings, including that of Oscar Grant.[136][137] Demonstrations were announced by several activists, which eventually resulted in disruptions to service. The protesters have stated that they did not want their protests to results in closures, and accused the BART police of using the protests as an excuse for disruption.[138] Protesters vowed to continue their protests every Monday until their demands were met.

On August 29, 2011, a coalition of nine public interest groups lead by Public Knowledge filed an Emergency Petition asking the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to declare "that the actions taken by the Bay Area Rapid Transit District (“BART”) on August 11, 2011 violated the Communications Act of 1934, as amended, when it deliberately interfered with access to Commercial Mobile Radio Service (“CMRS”) by the public" and "that local law enforcement has no authority to suspend or deny CMRS, or to order CMRS providers to suspend or deny service, absent a properly obtained order from the Commission, a state commission of appropriate jurisdiction, or a court of law with appropriate jurisdiction".[139][140]

In December 2011 BART adopted a new "Cell Service Interruption Policy" that only allows shutdowns of cell phone services within BART facilities "in the most extraordinary circumstances that threaten the safety of District passengers, employees and other members of public, the destruction of District property, or the substantial disruption of public transit service".[141] According to a spokesperson for BART, under the new policy the wireless phone system would not be turned off under circumstances similar to those in August 2011. Instead police officers would arrest individuals who break the law.[142]

In February 2012, the San Francisco District Attorney concluded that the BART Police Officer that shot and killed Charles Hill at the Civic Center BART station the previous July "acted lawfully in self defense" and will not face charges for the incident. A federal lawsuit filed against BART in January by Charles Hill's brother was proceeding.[143]

In March 2012, the FCC requested public comment on the question of whether or when the police and other government officials can intentionally interrupt cellphone and Internet service to protect public safety.[142]

Two BART track inspectors struck and killed by train

On the afternoon of October 19, 2013, two track inspectors—a BART employee and a contractor—were struck and killed near Walnut Creek by a train being moved for routine maintenance. A labor strike by BART's two major unions was underway at the time. The operator of the train was a BART manager, and had been a train operator two decades prior.[144]

Berkeley Hills Tunnel

On December 4, 2013, a BART train suffered mechanical braking problems and made an emergency stop in the Berkeley Hills Tunnel near Rockridge station. Eleven people were treated for smoke inhalation.[145]

See also

References

- ↑ "Monthly Average Exits" (XLSX). BART. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Total Annual Exits FY1973 - FY2014" (XLS). BART.gov (via: http://www.bart.gov/about/reports/ ). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 "BART System Facts". San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "BART – Car Types". Bay Area Rapid Transit. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Monthly Average Exits" (XLSX). BART. Retrieved Nov 6, 2014.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "History of BART (1946–1972)". BART. Archived from the original on January 6, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ See BART Composite Report, prepared by Parsons Brinkerhof Tutor Bechtel, 1962

- ↑ "BART– Not a Moment Too Soon". Los Angeles Times. September 13, 1972. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ↑ "BART First in Operation: 2nd great subway boom under way in many cities". The Bulletin. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Gillam, Jerry (November 15, 1972). "Safe Automated BART Train Controls Doubted". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ↑ Lembke, Daryl (November 16, 1972). "BART Manager Denies System Was Overcharged by Designers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ↑ "History of BART to the South Bay - San Jose Mercury News". Mercurynews.com. 2013-03-12. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ↑ "A History of BART: The Concept is Born". Bart.gov. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ↑ Fischer, Eric (January 17, 2010). "Golden Gate Transportation Facilities Plan Alternate 4". Flickr.com. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ↑ Fischer, Eric (January 17, 2010). "Golden Gate Transportation Facilities Plan Alternate 5". Flickr.com. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ↑ Holstege, Sean (July 24, 2002). "BART bond might make ballot in fall". Oakland Tribunal. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Cuff, Denis (May 29, 2007). "BART board wants to lessen waits". Contra Costa Times. Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- ↑ "Good move by BART". Contra Costa Times. October 1, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- ↑ Bay Area Rapid Transit. "Off-peak service reductions began Monday, September 14th". Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 BART goes solar at Orinda station, by Dennis Cuff, Contra Costa Times, July 10, 2008, access date July 13, 2008

- ↑ "Santa Clara VTA receives state funding to expand BART facilities", RT&S, December 7, 2012

- ↑ "Earthquake Safety Program Technical Information". Bay Area Rapid Transit District. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ↑ "Earthquake Safety Program". Bay Area Rapid Transit District. February 11, 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- ↑ "25 years after Loma Prieta quake: BART, then a lifeline, now stronger than ever.". BART. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- ↑ "San Francisco Earthquake History 1915-1989". The Museum of the City of San Francisco. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- ↑ "BART teams with UC Berkeley to adopt earthquake early warning system". Bay Area Rapid Transit District. September 29, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ Jordan, Melissa (March 20, 2013). "Late-night work over next 14 months will strengthen Transbay Tube against a quake". Bay Area Rapid Transit District. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- ↑ "Transbay Tube retrofit work wraps up early ending late night single tracking". Bay Area Rapid Transit District. December 2, 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (June 22, 2007). "BART'S New Vision: More, Bigger, Faster". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- ↑ "BART Train length". Google Groups: ba.transportation. July 3, 2000. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ Paul Garbutt (1997). "Facts and Figures". World Metro Systems. Capital Transport. pp. 130–131. ISBN 1-85414-191-0.

- ↑ "BART: Passenger Panic Worsened Tunnel Fire". CBS. Archived from the original on December 4, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "BART reports record ridership and progress on escalator repair". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). August 9, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Monthly Ridership Reports (September 2012)" (XLS). BART. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ↑ "BART marks all-time highest ridership day in 40 years of service". BART. October 31, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ↑ "World Series parade boosts BART ridership to highest day ever – past half-million". BART. November 4, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ↑ "11.01.2009 BART customers continue to set ridership records". Bart.gov. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ↑ "BART ridership soars during Bay Bridge closure". KTVU. August 30, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- ↑ "BART shatters Saturday ridership record, adds capacity for Sunday". BART. October 7, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Pride Parade Service Breaks Sunday Ridership Record". BART. June 30, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ↑ Bay Area Rapid Transit. "October BART ridership soaring". Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- ↑ "BART reports record ridership and progress on escalator repair". BART. August 9, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ↑ "BART to run on Sunday schedule Christmas Day". BART. December 21, 2006. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ↑ "New Train Car Project". BART. October 4, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ↑ "BART Service Hours, Holiday Schedule". BART. Archived from the original on January 6, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ "Why doesn't BART run 24 hours?". BART. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "BART – Overview". BART. Archived from the original on August 14, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "All Nighter Bus Service". 511 SF Bay Area Travel Guide. Archived from the original on May 21, 2007. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- ↑ "BART Unveils Modern Fare Gates and New Ticket Vending Machines". Business Wire. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "BART – ticket refunds and exchanges". BART. Archived from the original on January 28, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2007.[

- ↑ Jon Carroll (December 6, 2000). "Tiny Tickets Ha Ha Ha Ha". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ "QuickPlanner >> Results between Downtown Berkeley and North Berkeley". BART. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ "QuickPlanner >> Results between Pittsburg/Bay Point and SFO". BART. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ↑ "BART Ticket Types". BART. Archived from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Capitol Corridor Ride Guide" (PDF). The Capitol Corridor. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ "The Capitol Corridor: BART Connections". The Capitol Corridor. Archived from the original on October 11, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ "SFMTA Advises Customers of Muni Fare Increases for January 2010". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA). December 17, 2009. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Today’s free lecture: fare idea falls flat". Inside Bay Area. September 19, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ↑ Michael Cabanatuan (November 19, 2005). "Underground, but not unconnected – BART offers wireless service to riders". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ↑ BART expands wireless access to Transbay Tube, BART, December 21, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- ↑ BART expands wireless network to underground stations in downtown Oakland, BART, August 27, 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ "WiFi Rail Inc. to provide wifi access on BART system". BART. February 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ↑ "WiFi Rail Tube Access". KRON 4. June 2009. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ Elinson, Zusha (August 11, 2011). "BART Cuts Cell Service to Foil Protest". The Bay Citizen. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 "Library-a-Go-Go comes to El Cerrito del Norte BART Station". Bart.gov. June 15, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ↑ "In California, a New ATM for Books Debuts". Libraryjournal.com. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Self-Service to the People". Libraryjournal.com. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Library book lending machine opens at Millbrae BART Station". Bart.gov. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ↑ Fischer, Eric. "San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District: General Map: May 2, 1960 Routes , Flickr – Photo Sharing!". Flickr. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Bart Express Connecting Bus Service". ALL-Transit.com. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ "Long-Term Parking for Travelers". BART. Archived from the original on January 6, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ "BART parking overview". BART. Archived from the original on January 6, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ "BART breaks ground Wednesday on Oakland Airport Connector". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). October 20, 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ Roth, Matthew (October 21, 2010). "Streetsblog San Francisco » BART Holds Groundbreaking Ceremony for the Oakland Airport Connector". Sf.streetsblog.org. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 "New BART service to Oakland International Airport now open". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). November 21, 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Airport Connections Guide". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Oakland Airport Connector, Oakland, USA". 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ "BART Police". BART. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "BART's Livermore role reviewed". Contra Costa Times. July 17, 2003. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "BART 2005 Annual Report" (PDF)."BART 2005 Annual Report" (TXT). BART.gov. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ "Sustainable BART".

- ↑ Griffin, Melissa (13 June 2013). "BART labor seeking more money for not laboring". The San Francisco Examiner.

- ↑ "San Francisco rail strike continues as commuters face third day of chaos". The Guardian (London). AP. 3 July 2013.

- ↑ ""Why can't the trains be longer?" Some background to explain". BART. September 25, 2008. Archived from the original on August 27, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "FY08 Short Range Transit Plan and Capital Improvement Program" (PDF). BART. September 2007. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- ↑ "BART Car ills". San Jose Mercury News. February 23, 1990. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Elinson, Zusha (March 5, 2011). "BART Seats: Where Bacteria Blossom". Bay Citizen. Accessed March 8, 2011.

- ↑ Elinson, Zusha (April 12, 2011). "BART Plans to Spend $2 Million to Replace Grimy Seats". Bay Citizen. Accessed April 13, 2011.

- ↑ Elinson, Zusha (April 6, 2012). "BART’s New Seats (a Few) Make Debut". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 "New seats now in all trains". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). January 2, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ↑ "BART Renovation Nears Completion". Business Wire. October 9, 2003. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ↑ "WESTCODE, INC., Plaintiff, v. DAIMLER CHRYSLER RAIL SYSTEMS (NORTH AMERICA) INC., f/k/a AEG TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS, INC., Defendant." (PDF).

- ↑ Oakland North Radio, October 24, 2010. Accessed April 10, 2012

- ↑ Robert Paniagua (March 2008). "Rohr cars and it's dictivtive sounds". Railroad Net Forum. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ↑ http://bartrage.com/node/1479

- ↑ Richman, Josh (May 10, 2012). "BART board approves contract for 410 new train cars". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ Bowen, Douglas John (May 11, 2012). "BART taps Bombardier; U.S. content at issue". Railway Age. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "BART Board approves additional 365 cars for Fleet of the Future". BART. November 21, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 "Board Meeting Agenda" (PDF). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. November 21, 2013. pp. 91–92. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ↑ "New Train Car Project; New Features". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "New Train Car Project New Features". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ↑ Cuff, Denis (February 26, 2015). "BART changes new train car design to satisfy disabled riders' concerns". Contra Costa Times. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ "New Train Car Project Delivery Plan". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ W. S. Homburger. "The impact of a new rapid transit system on traffic on parallel highway facilities". 1029-0354, Volume 4, Issue 3 (Transportation Planning and Technology). Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Fact Book Glossary - Mode of Service Definitions". American Public Transportation Association. 2013. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

- ↑ "Passenger Rail Issues". East Bay Bicycle Coalition. Archived from the original on February 22, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ↑ "Rapid transit". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved February 27, 2008.; "Metro". International Association of Public Transport. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ↑ Goll, David (March 8, 2009). "BART opens bids on project, moves a step closer to Silicon Valley". Silicon Valley/San Jose Business Journal. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "BART Metro Vision Update" (PDF). Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). April 25, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ↑ "Celebrating 40 Years of Service 1972 • 2012 Forty BART Achievements Over the Years" (PDF). Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ Record of Decision, Federal Transportation Commission. 2010. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ↑ Berryessa Extension Factsheet, Bay Area Rapid Transit. 2010. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ↑ East Contra Costa BART Extension (eBART), BART. 2010. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ↑ Unger, Stephen. "September 1973 Newsletter". IEEE Committee on Social Implications of Technology (CSIT). IEEE. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ↑ Geoffrey Hunter, Oakland Fire Department, 2005, p95 ISBN 978-0-7385-2968-4

- ↑ Gordon, Rachel; Bulwa, Demian; Jones, Carolyn (October 15, 2008). "BART train kills worker on tracks in Concord". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ↑ Eskenazi, Joe (February 2, 2009). "BART Accused of Being Late – in Paying Out to Survivors of Track Inspector Killed by Train". San Francisco News - The Snitch. Blogs.sfweekly.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ↑ Jill Tucker; Kelly Zito; Heather Knight (January 2, 2009). "Deadly BART brawl – officer shoots rider, 22". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 4, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- ↑ Eliott C. McLaughlin; Augie Martin; Dan Simon (2009). "Spokesman: Officer in subway shooting has resigned". CNN. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- ↑ Elinor Mills (2009). "Web videos of Oakland shooting fuel emotions, protests". CNET Networks. Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- ↑ Demian Bulwa; Charles Burress; Matthew B. Stannard; Matthai Kuruvilaurl (January 8, 2009). "Protests over BART shooting turn violent". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ↑ "BART Shooting: Family Suing BART For $25 Million". KTVU. 2009. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ↑ "Jury Finds Mehserle Guilty Of Involuntary Manslaughter". KTVU. July 8, 2010. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ↑ Bulwa, Demian (June 14, 2011). "Johannes Mehserle, ex-BART officer, leaves jail". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ↑ Upton, John (July 25, 2011). "BART Police Release Video of Shooting – Pulse of the Bay". The Bay Citizen. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ↑ Murphy, David (August 13, 2011). "To Prevent Protests, San Francisco Subway Turns Off Cell Signals, August 13, 2011". PC Magazine. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ↑ "S.F. subway muzzles cell service during protest". CNET.

- ↑ "Questions, Complaints Arise Over BART Cutting Cell Phone Service". KTVU.

- ↑ "Leland Yee scolds BART over cell phone blackout". KGO-TV.

- ↑ "BART Under Fire From Hackers, Critics, Employees". KTVU.

- ↑ "Hackers Escalate Attack On BART; User IDs Stolen". KTVU.

- ↑ "Shadowy Internet group Anonymous attacks BART website". San Francisco Examiner.

- ↑ "BART runs without problems despite protest threats". KGO-TV.

- ↑ "BART Warns Commuters Of Potential Protest Disruptions". KTVU.

- ↑ "BART Warns Commuters Of Potential Protest Disruptions". NBC Bay Area.

- ↑ "Protesters storm BART, slow commute out of San Francisco". San Francisco Examiner.

- ↑ "BART warns passengers of possible protests at San Francisco stations Thursday". San Francisco Examiner.

- ↑ Protest plan for OpBART-3 Plan for further protests by OpBART.

- ↑ "In the Matter of the Petition of Public Knowledge et al. for Declaratory Ruling that Disconnection of Telecommunications Services Violates the Communications Act", Harold Feld, Legal Director, and Sherwin Siy, Deputy Legal Director, of Public Knowledge before the Federal Communications Commission, August 29, 2011

- ↑ Crawford, Susan (September 25, 2011). "Phone, Web Clampdowns in Crises Are Intolerable". Bloomberg News.

- ↑ "Cell Service Interruption Policy" (PDF). Bay Area Rapid Transit District. December 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ↑ 142.0 142.1 Wyatt, Edward (March 2, 2012). "F.C.C. Asks for Guidance on Whether, and When, to Cut Off Cellphone Service". The New York Times.

- ↑ Crowell, James (February 22, 2012). "BART Officer Who Shot Charles Hill, 'Acted Lawfully' According To District Attorney". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Gafni, Matthias; Peterson, Gary; Nelson, Katie (October 19, 2013). "Two BART workers struck, killed by train near Walnut Creek". San Jose Mercury News.

- ↑ Shields, Brian (December 4, 2013). "BART Brake Smoke Causes Injuries in Caldecott Tube". KRON4. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

Further reading

- Owen, Wilfred (1966). The metropolitan transportation problem. Anchor Books.

- BART: a study of problems of rail transit. California. Legislature. Assembly. Committee on Transportation. 1973.

- Richard Grefe (1976). A history of the key decisions in the development of Bay Area Rapid Transit. National Technical Information Service.

- E. Gareth Hoachlander (1976). Bay Area Rapid Transit: who pays and who benefits?. University of California.

- Cervero, Robert (1998). The transit metropolis: a global inquiry. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-591-6.

- University of California (1966). The San Francisco Bay area: its problems and future, Volume 2. University of California.

- Typographica (October 8, 2005). "BART Wayfinding". Typographica (Typographica).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to BART. |

- Bay Area Rapid Transit

- Engineering Geology of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) System, 1964–75

- BART Map/Schedule Map/Schedule using Google Maps API

- BART widget, a self-contained trip planner for Mac OS X Dashboard

- BARTsmart Another BART Widget, featuring BART schedules and news

- Map of BART and rail network in simplified diagrammatic, rather than geographically accurate

- iSubwayMaps.com iPod, alternative predating official BART offering (map only)

- Shuttles serving BART stations at 511.org

- Pictures of BART on world.nycsubway.org

- Network map (real-distance)

- Bay Area Rapid Transit at the Wayback Machine (archived May 17, 1998)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||