Battle of Torvioll

| Battle of Torvioll | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman wars in Europe | |||||||

A woodcut of the confrontation between Skanderbeg's forces and the Ottoman Turks | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,000 men (8,000 cavalry, 7,000 infantry) | 25,000–40,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

100–120 dead, many more wounded (primary sources) | 8,000–22,000 dead, 2,000 captured | ||||||

| ||||||

The Battle of Torvioll, also known as the Battle of Lower Dibra, was fought on 29 June 1444 on the Plain of Torvioll, in what is modern-day Albania. Skanderbeg was an Ottoman captain of Albanian origin who decided to go back to his native land and take the reins of a new Albanian rebellion. He, along with 300 other Albanians fighting at the Battle of Niš, deserted the Ottoman army to head towards Krujë, which fell quickly through a subversion. He then formed the League of Lezhë, a confederation of Albanian princes united in war against the Ottoman Empire. Murad II, realizing the threat, sent one of his most experienced captains, Ali Pasha, to crush the rebellion with a force of 25,000 men.

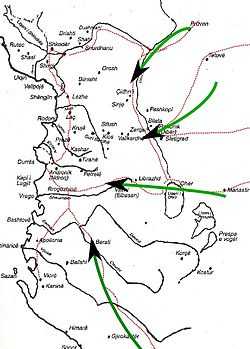

Skanderbeg expected a reaction so he moved with 15,000 of his own men to defeat Ali Pasha's army. The two met in the Plain of Torvioll where they camped opposite of each other. The following day, 29 June, Ali came out of his camp and saw that Skanderbeg had positioned his forces at the bottom of a hill. Expecting a quick victory, Ali ordered all of his forces down the hill to attack and defeat Skanderbeg's army. Skanderbeg expected such a maneuver and prepared his own stratagem. Once the opposing forces were engaged and the necessary positioning was achieved, Skanderbeg ordered his forces hidden in the forests behind the Turkish army to strike their rear flanks. The result was devastating for the Ottomans, whose entire army was routed with its commander nearly being killed.

The victory lifted the morale of the Christian princes of Europe and was recognized as a great victory over the Muslim Ottoman Empire whose expansions they could not withhold by themselves. Murad thus realized the effect Skanderbeg's rebellion would have on his realm and continued to take proper measures for his defeat, resulting in twenty-five years of war.

Background

George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, the son of the powerful prince John Kastrioti, had been a vassal of the Ottoman Empire as a sipahi, or cavalry commander. After his participation in the Ottoman loss at the Battle of Niš, Skanderbeg deserted the Ottoman army and rushed to Albania alongside 300 other Albanians. By forging a letter from Murad II to the Governor of Krujë, he became lord of the city in November 1443.[1] Hungarian captain John Hunyadi's continued operations against Sultan Murad II gave Skanderbeg time to prepare an alliance of the Albanian nobles. Skanderbeg invited all of Albania's nobles to meet in the Venetian-held town of Alessio (Lezhë) on 2 March 1444. Alessio was chosen as the meeting point because the town had once been the capital of the Dukagjini family and to induce Venice to lend aid to the Albanian movement.[2] Among the nobles that attended were George Arianiti, Paul Dukagjini, Andrea Thopia, Lekë Dushmani, Teodor Korona, Peter Spani, Lekë Zaharia, and Paul Stres Balsha. Here they formed the League of Lezhë, a confederation of all of the major Albanian princes in alliance against the Ottoman Empire.[3] The chosen captain (Albanian: Kryekapedan) of this confederation was Skanderbeg.[4] The League's first military challenge came in the spring of 1444, when Skanderbeg's scouts reported that the Ottoman army was planning to invade Albania. Skanderbeg planned to move towards the anticipated entry point and prepared for an engagement.[5]

Campaign

Prelude

Ali Pasha, one of Murad's most favored commanders, left Üsküp (Skopje) in June 1444 with an army of 25,000–40,000 troops[6][7] and headed in Albania's direction.[8] Having brought together an army of 15,000 men (8,000 cavalry and 7,000 infantry)[9] from the League of Lezhë, Skanderbeg exhorted to his soldiers the importance of the upcoming campaign. Orders were given for the distribution of soldiers' pay and for religious services to be held.[10] Afterwards, Skanderbeg and his army headed towards the planned place of battle in Lower Dibra, which is thought to be the Plain of Shumbat, then called the Plain of Torvioll, north of Peshkopi.[11] On the way there, he marched through the Black Drin valley and appeared at the expected Ottoman entry point.[3] Skanderbeg had chosen the plain himself: it was 11.2 kilometres (7.0 mi) long and 4.9 kilometres (3.0 mi) wide, surrounded by hills and forests. After camping near Torvioll, Skanderbeg placed 3,000 men under five commanders, Hamza Kastrioti, Muzaka of Angelina, Zecharia Gropa, Peter Emanueli, and John Musachi, in the surrounding forests with orders to attack the Ottoman wings and rear only after a given signal. While Skanderbeg was preparing his ambush, the Ottoman Turks under Ali Pasha arrived and encamped opposite his forces.[10] The night before the battle, the Ottomans celebrated the coming day, whereas the Albanians extinguished all their campfires and those who were not on guard were directed to rest. Parties of Ottomans made approaches to the Albanian camp and provoked Skanderbeg's soldiers, but they remained quiet. Skanderbeg sent out a scouting party to obtain information about the Ottoman army and ordered his cavalry to engage in small skirmishes.[12]

Albanian positioning

On the morning of 29 June,[13] Skanderbeg arranged his army for battle. Apart from the 3,000 warriors hidden behind the Ottoman army, Skanderbeg left another reserve force of 3,000 under the command of Vrana Konti.[10] The Albanian army was positioned in a crescent shape curving inwards. They were divided into three groups, each composed of 3,000 men. They were all placed at the bottom of a hill, with the intention of luring the Ottoman cavalry-based army into a downhill charge. The Albanian left wing was commanded by Tanush Thopia with 1,500 horsemen and an equal number of infantrymen. On the right wing, Skanderbeg placed Moisi Golemi in the same manner as Thopia.[12] In front of the wings, foot archers were placed to lure the Ottomans in.[14] In the center, there were 3,000 men under the command of Skanderbeg and Ajdin Muzaka. One-thousand horsemen were placed in front of the main division with orders to blunt the initial Turkish cavalry charge. An equal number of archers, trained to accompany the horses, was placed next to these horsemen. The main body of infantry, commanded by Ajdin Muzaka, was placed behind the archers.[15]

Battle

After the army was marshaled, Skanderbeg would not permit the trumpets to give the signal for battle until he saw Ali Pasha advancing. After looking upon the Albanian army, the Pasha ordered his army to charge with one of the units ahead of the rest. The Albanian front line retreated; Skanderbeg sent a body of horsemen to prevent the line from breaking and marshaled the retreating troops back to their places.[15] Ali Pasha believed he had the Albanians trapped.[3] The same situation occurred on the left wing and, when all were in their places, the army prepared for the main offensive.[15] As it began, the wings were fiercely led on by Thopia and Golemi and pushed back the Ottoman wings. In the centre, Skanderbeg assaulted a selected battalion. When the proper signal was given, the 3,000 horsemen hidden in the woods sprung out and charged into the Ottoman rear, causing large parts of their army to rout. The wings of the Albanian army turned towards the Ottoman centre's flanks. Ajdin Muzaka, having charged the Turkish centre, was met by fierce resistance and the Turks continued to pour in fresh forces until Vrana Konti came in with his reserves and decided the battle.[16] The Turkish army was surrounded.[3] The Ottoman front ranks were annihilated except for 300 soldiers. Ali Pasha's personal battalion fled although the commander nearly met his death.[16]

Aftermath

8,000[13] to 22,000[17] Turks died in the battle, while 2,000 were captured. The Albanians were originally attributed to have lost as little as 120 men,[17] but modern sources suggest a higher figure of 4,000 Albanians dead and wounded.[3] Skanderbeg remained quiet in his camp for the remainder of that day and the following night. Having addressed his troops, he directed his infantry to mount the captured horses. The spoils of the victory were abundant and even the wounded took part in the pillaging. Skanderbeg thereafter ordered a general retreat toward Krujë.[18] Skanderbeg's victory was praised through the rest of Europe.[19][20] The European states thus began to consider a crusade to drive the Ottomans out of Europe.[19][21] When Ali Pasha returned to Adrianople (Edirne), he explained to the sultan that the loss should be attributed to his forces and the "fortunes of war" and not his generalship.[22] The battle of Torvioll thus opened up the quarter-century war between Skanderbeg's Albania and the Ottoman Empire.[11]

Kenneth Meyer Setton claims that majority of accounts on Skanderbeg's activities in the period 1443–1444 "owe far more to fancy than to fact." According to him, after Skanderbeg was allegedly victorious in Torviolli, the Hungarians are said to have sung praises about him and urged Skanderbeg to join the alliance of Hungary, the Papacy and Burgundy against the Turks.[23]

Notes

- ↑ Frashëri p. 134.

- ↑ Frashëri p. 135.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Frashëri p. 139.

- ↑ Frashëri pp. 136–138.

- ↑ Fine pp. 557.

- ↑ Moore p. 45.

- ↑ Frashëri pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Noli p.21.

- ↑ Gibbon p. 464.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Moore p. 46.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Frashëri p. 141.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Moore p. 47.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hodgkinson p. 75.

- ↑ Moore pp. 47–48.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Moore p. 48

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Moore p. 49.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Franco p. 58.

- ↑ Moore p. 50.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Jacques pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Noli p.22

- ↑ Moore p. 51

- ↑ Moore pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Setton p. 73.

References

- Fine, John (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-08260-4

- Francione, Gennaro (2006) [2003]. Aliaj, Donika, ed. Skënderbeu, një hero modern : (Hero multimedial) [Skanderbeg, a modern hero (Hero multimedia)] (in Albanian). Translated by Tasim Aliaj. Tiranë, Albania: Shtëpia botuese "Naim Frashëri". ISBN 99927-38-75-8.

- Franco, Demetrio (1539), Comentario de le cose de' Turchi, et del S. Georgio Scanderbeg, principe d' Epyr, Altobello Salkato, ISBN 99943-1-042-9

- Frashëri, Kristo (2002), Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, 1405–1468 (in Albanian), Botimet Toena, ISBN 99927-1-627-4

- Gibbon, Edward (1957), History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Peter Fenelon Collier & Son

- Hodgkinson, Harry (1999), Scanderbeg: From Ottoman Captive to Albanian Hero, Centre for Albanian Studies, ISBN 978-1-873928-13-4

- Jacques, Edwin (1995), Shqiptarët: Historia e popullit shqiptar nga lashtësia deri në ditët e sotme, Mcfarland, ISBN 0-89950-932-0

- Moore, Clement Clarke (1850), George Castriot: Surnamed Scanderbeg, King of Albania, D. Appleton & Company

- Noli, Fan Stilian (2009), Scanderbeg, General Books, ISBN 978-1-150-74548-5

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1978), The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571, DIANE Publishing, ISBN 978-0-87169-127-9

External links

- Beteja e Torviollit, 1444 - Excerpt from Marin Barleti's Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum Principis (Albanian)

- George Castriot, Surnamed Scanderbeg, King of Albania by Clement Clarke Moore - See pages 45–55 for a description of the Battle of Torvioll