Battle of Singapore

The Battle of Singapore, also known as the Fall of Singapore, was fought in the South-East Asian theatre of the Second World War when the Empire of Japan invaded the British stronghold of Singapore. Singapore was the major British military base in South-East Asia and nicknamed the "Gibraltar of the East". The fighting in Singapore lasted from 8–15 February 1942.

It resulted in the capture of Singapore by the Japanese and the largest surrender of British-led military personnel in history.[4] About 85,000–120,000 British, Indian and Australian troops became prisoners of war,[2][3] joining 50,000 taken by the Japanese in the earlier Malayan Campaign. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the ignominious fall of Singapore to the Japanese the "worst disaster" and "largest capitulation" in British military history.[5] However a wartime British general, Archibald Wavell, blamed the Australians for the loss of Singapore.[6]

Background

Outbreak of war

The Allies had imposed a trade embargo on Japan in response to its continued campaigns in China. Seeking alternative sources of necessary materials for its Pacific War against the Allies, Japan invaded Malaya.[7] Singapore—to the south—was connected to Malaya by the Johor–Singapore Causeway. The Japanese saw it as a port which could be used as a launching pad against other Allied interests in the area and to consolidate the invaded territory.

Invasion of Malaya

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Singapore |

.svg.png) |

| Early history of Singapore (pre-1819) |

|

| Founding of modern Singapore (1819–26) |

| Straits Settlements (1826–67) |

| Crown colony (1867–1942) |

| Battle of Singapore (1942) |

| Japanese Occupation (1942–45) |

|

| Post-war period (1945–55) |

|

| Internal self-government (1955–62) |

|

| Merger with Malaysia (1962–65) |

|

| Republic of Singapore (1965–present) |

|

| Singapore portal |

The Japanese 25th Army invaded from Indochina, moving into northern Malaya and Thailand by amphibious assault on 8 December 1941.[8] This was virtually simultaneous with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which was meant to deter the US from intervening in Southeast Asia. Thailand initially resisted, but soon had to yield and allow the Japanese to use their military bases to invade the European colonies in Southeast Asia. The Japanese then proceeded overland across the Thai–Malayan border to attack Malaya. At this time, the Japanese began bombing strategic sites in Singapore, and air raids were conducted on Singapore from 29 December onwards.

The Japanese 25th Army was resisted in northern Malaya by III Corps of the British Indian Army. Although the 25th Army was outnumbered by Allied forces in Malaya and Singapore, Japanese commanders concentrated their forces. The Japanese were superior in close air support, armour, coordination, tactics and experience. Moreover, the British forces repeatedly allowed themselves to be outflanked, believing—despite repeated flanking attacks by the Japanese—that the Malayan jungle was impassable. Prior to the Battle of Singapore the most resistance was met at the Battle of Muar.[9] The Imperial Japanese Army Air Force was more numerous, and better trained than the second-hand assortment of untrained pilots and inferior allied equipment remaining in Malaya, Borneo and Singapore. Their superior fighters—especially the Nakajima Ki-43—helped the Japanese to gain air supremacy. The Allies had no tanks and few armoured vehicles, which put them at a severe disadvantage.

The battleship HMS Prince of Wales, the battlecruiser HMS Repulse and four destroyers (Force Z) reached Malaya before the Japanese began their air assaults. This force was thought to be a deterrent to the Japanese. Their aircraft, however, sank the capital ships, leaving the east coast of the Malayan peninsula exposed and allowing the Japanese to continue their amphibious landings. Japanese forces quickly isolated, surrounded, and forced the surrender of Indian units defending the coast. They advanced down the Malayan peninsula overwhelming the defences, despite their numerical inferiority. The Japanese forces also used bicycle infantry and light tanks, allowing swift movement through the jungle.

Although more Allied units—including some from the Australian 8th Division—joined the campaign, the Japanese prevented the Allied forces from regrouping. They also overran cities and advanced toward Singapore. The city was an anchor for the operations of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM), the first Allied joint command of the Second World War. Singapore controlled the main shipping channel between the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. An effective ambush was carried out by the 2/30th Battalion on the main road at the Gemenceh River near Gemas on 14 January, although exact number of Japanese casualties is still in dispute.[10][11]At Bakri, from 18 to 22 January, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Anderson's 2/19th Battalion repeatedly fought through Japanese positions before running out of ammunition near Parit Sulong.[12]Anderson's battalion was forced to leave behind about 110 Australian and 40 Indian wounded that were massacred by the Japanese.[13]For his leadership, in the fighting withdrawal, Anderson was awarded the Victoria Cross. [14] On 24 January, a determined counterattack from Lieutenant-Colonel John Parkin's 5/11th Sikh Regiment in the area of Niyor, near Kluang and a successful ambush by the 2/18th Australian Battalion bought valuable time and permitted Brigadier Harold Taylor's Eastforce to withdraw from eastern Jahore.[15][16][17]On 31 January, the last Allied forces left Malaya and Allied engineers blew a hole in the causeway linking Johor and Singapore.

Prelude

During the weeks preceding the invasion, the Allied force suffered a number of both subdued and openly disruptive disagreements amongst its senior commanders,[18] as well as pressure from the Australian Prime Minister, John Curtin.[19] Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, commander of the garrison, had 85,000 soldiers, the equivalent, on paper at least, of just over four divisions. There were at least 70,000 front-line troops in 38 infantry battalions—13 British, six Australian, 17 Indian, two Malayan—and three machine-gun battalions. The newly arrived British 18th Infantry Division—under Major-General Merton Beckwith-Smith—was at full strength, but lacked experience and appropriate training; most of the other units were under strength, a few having been amalgamated due to heavy casualties, as a result of the mainland campaign. The local battalions had no experience and in some case no training.[20]

Percival gave Major-General Gordon Bennett's two brigades from the Australian 8th Division responsibility for the western side of Singapore, including the prime invasion points in the northwest of the island. This was mostly mangrove swamp and jungle, broken by rivers and creeks. In the heart of the "Western Area" was RAF Tengah, Singapore's largest airfield at the time. The Australian 22nd Brigade was assigned a 10 mi (16 km) wide sector in the west, and the 27th Brigade had responsibility for a 4,000 yd (3,700 m) zone just west of the Causeway. The infantry positions were reinforced by the recently arrived Australian 2/4th Machine-Gun Battalion. Also under Bennett's command was the 44th Indian Infantry Brigade.

The Indian III Corps under Lieutenant-General Sir Lewis Heath—including the Indian 11th Infantry Division, (Major-General B. W. Key), the British 18th Division and the 15th Indian Infantry Brigade—was assigned the north-eastern sector, known as the "Northern Area". This included the naval base at Sembawang. The "Southern Area"—including the main urban areas in the south-east—was commanded by Major-General Frank Keith Simmons. His forces comprised about 18 battalions, including the Malayan 1st Infantry Brigade, the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force Brigade and Indian 12th Infantry Brigade.

From aerial reconnaissance, scouts, infiltrators and high ground across the straits, such as at Istana Bukit Serene, the Sultan of Johor's palace, the Japanese commander—General Tomoyuki Yamashita—and his staff gained excellent knowledge of the Allied positions. Yamashita and his officers stationed themselves at Istana Bukit Serene and the Johor state secretariat building—the Sultan Ibrahim Building—to plan for the invasion of Singapore.[21][22]

Although advised by his top military personnel that Istana Bukit Serene was an easy target, Yamashita was confident that the British Army would not attack the palace because it was the pride and a possession of the Sultan of Johor. Yamashita's prediction was correct, as the British Army did not dare attack the palace.

From 3 February, the Allies were shelled by Japanese artillery and air attacks on Singapore intensified over the next five days. The artillery and air bombardment strengthened, severely disrupting communications between Allied units and their commanders and affecting preparations for the defence of the island.

It is a commonly repeated misconception that Singapore's famous large-calibre coastal guns were ineffective against the Japanese because they were designed to face south to defend the harbour against naval attack and could not be turned round to face north. In fact, most of the guns could be turned, and were indeed fired at the invaders. However, the guns - which included one battery of three 15 in (380 mm) weapons and one with two 15 in (380 mm) guns — were supplied mostly with armour-piercing (AP) shells and few high explosive (HE) shells. AP shells were designed to penetrate the hulls of heavily armoured warships and were mostly ineffective against infantry targets. Military analysts later estimated that if the guns had been well supplied with HE shells the Japanese attackers would have suffered heavy casualties, but the invasion would not have been prevented by this means alone.

Yamashita had just over 30,000 men from three divisions: the Imperial Guards Division under Lieutenant-General Takuma Nishimura, the 5th Division under Lieutenant-General Takuro Matsui and the 18th Division under Lieutenant-General Renya Mutaguchi. The elite Imperial Guards units included a light tank brigade.

Percival incorrectly guessed the Japanese would land forces on the North East side of Singapore. This was encouraged by the deliberate movement of enemy troops in this sector to deceive the British. Therefore a large portion of defence equipment and resources was allocated to the North Eastern sector and the Australian sector had no serious fixed defence works or obstacles. A daring Australian night patrol in the days leading up to the Japanese attack discovered hidden naval assault boats and a concentration of troops. The Australians requested the immediate shelling of these positions to disrupt the Japanese preparations but Percival and his senior commanders ignored the request, believing that the real assault would come in the North Eastern sector, not the North West.

Battle

Japanese landings

Blowing up the causeway had delayed the Japanese attack for over a week. Prior to the main assault the Australians were subjected to a terrific artillery bombardment that cut telephone lines and effectively isolated forward units from rear areas. Even at this stage, a counter artillery barrage as a response could have been mounted by the British on the coastline opposite the Australians that would have caused casualties and disruption among the Japanese assault troops. But the bombardment of the Australians was not seen as a prelude to imminent attack, despite its ferocity exceeding anything the Allies had experienced thus far in the campaign.

At 20:30 on 8 February, Australian machine gunners opened fire on vessels carrying the first wave of 4,000 troops from the 5th and 18th Divisions toward Singapore island. The Japanese assaulted Sarimbun Beach, in the sector controlled by the Australian 22nd Brigade under Brigadier Harold Burfield Taylor. Spotlights had been sited by a British unit on the beaches to enable the Australians to clearly see any attacking forces on the water in front of them. But the British commander of this unit could not be contacted when the communication lines were cut, so the Australians were forced to fire into the darkness at the sound of approaching boats or at their silhouettes from the few burning vessels that had been hit by lucky mortar fire. What was supposed to be an illuminated killing field was instead a difficult, dark area that favoured the attackers more than the defenders. Once the Japanese reached the darkened shorelines, they could easily disperse into the undergrowth and jungle terrain where they would be unseen by the Australians in their static, fixed positions. This allowed the mobile but hidden Japanese to either surround and destroy pockets of Australian resistance or simply bypass them to reach other objectives. As was the case throughout the Malayan and Singapore campaign, the fast moving, mobile Japanese always had the advantage over the static Allied positions, who because of limited visibility caused by the terrain, could rarely tell if they were being attacked by small or large numbers of their concealed enemies.

Fierce fighting raged all day,[lower-alpha 1]</ref> but eventually the increasing Japanese numbers—and the superiority of their artillery, aircraft and military intelligence—began to take their toll. In the northwest of the island they exploited gaps in the thinly spread Allied lines such as rivers and creeks. By midnight, the two Australian brigades had lost communications with each other, and the 27nd Brigade retreated without permission.[23] Clifford Kinvig, a senior lecturer at Sandhurst Royal Military Academy and others, point the finger of blame at the commander of the 27th Brigade, Brigadier Duncan Maxwell for his defeatist attitude[24] and not properly defending the the sector between the Causeway and the Kranji River.[25]

In the documentary No Prisoners (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Four Corners series, 2002), Major John Wyett, a 8th Division staff officer, claims the commander of the Australian 22nd Brigade cracked under the pressure and says, "Taylor was wandering around rather like a man in a sleep walk. He was utterly, utterly, you know, shell-shocked and not able to do very much."[25] At 01:00, more Japanese troops were landed in the northwest of the island and the last Australian reserves went in. Near dawn on 9 February, elements of the 22nd Brigade were overrun or surrounded; the 2/18th Australian Infantry Battalion had lost more than half of its personnel, killed, wounded, captured or in desertions.[lower-alpha 2]</ref>

Air war

Air cover was provided by only ten Hawker Hurricane fighters of RAF No. 232 Squadron, based at Kallang Airfield. This was because Tengah, Seletar and Sembawang were in range of Japanese artillery at Johor Bahru. Kallang Airfield was the only operational airstrip left; the surviving squadrons and aircraft were withdrawn by January to reinforce the Dutch East Indies.[26]

At 04:15 on 8 December 1941, Singapore was subjected to aerial bombing for the first time by long-range Japanese aircraft, such as the Mitsubishi G3M2 "Nell" and the Mitsubishi G4M1 "Betty", based in Japanese-occupied Indochina. The bombers struck the city centre as well as the Sembawang Naval Base and the island's northern airfields. After this first raid, throughout the rest of December, there were a number of false alerts and several infrequent and sporadic hit-and-run attacks on outlying military installations such as the Naval Base, but no actual raids on Singapore City. The situation had become so desperate, it included a British soldier firing a Vickers machine gun from the middle of a road at any aircraft that passed. He could only say: "The bloody bastards will never think of looking for me in the open, and I want to see a bloody plane brought down."[27]

On 9 December, the Royal Australian Air Force's 8th Squadron abandoned the Kota Baharu airfield without permission and departed for Singapore, after 17 Japanese bombers attacked in two waves,[28][29] forcing Brigadier Billy Key's Indian 8th Brigade to concede defeat in the Battle of Kelantan.[30]

The next recorded raid on the city occurred on the night of 29/30 December, and nightly raids ensued for over a week, only to be accompanied by daylight raids from 12 January 1942 onward. In the days that followed, as the Japanese army drew ever nearer to Singapore Island, the day and night raids increased in frequency and intensity, resulting in thousands of civilian casualties, up to the time of the British surrender.

During December, 51 Hurricane Mk II fighters were sent to Singapore, with 24 pilots, the nuclei of five squadrons. They arrived on 3 January 1942, by which stage the F2A Buffalo squadrons had been overwhelmed. No. 232 Squadron was formed and No. 488 Squadron RNZAF, a Buffalo squadron had converted to Hurricanes. 232 Squadron became operational on 20 January and destroyed three Nakajima Ki-43 "Oscars" that day,[31] for the loss of three Hurricanes. However, like the Buffalos before them, the Hurricanes began to suffer severe losses in intense dogfights.

During the period 27 January–30 January, another 48 Hurricanes (the Mk IIA variant), arrived with No. 226 Group (four squadrons) on the aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable, from which they flew to airfields code-named P1 and P2, near Palembang, Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies. However, the staggered arrival of the Hurricanes — along with inadequate early warning systems — meant that Japanese air raids were able to destroy many of the Hurricanes on the ground in Sumatra and Singapore.

On the morning of 8 February, a series of aerial dogfights took place over Sarimbun Beach and other western areas. In the first encounter, the last ten Hurricanes were scrambled from Kallang Airfield to intercept a Japanese formation of about 84 planes, flying from Johor to provide air cover for their invasion force.[26] In two sorties, the Hurricanes shot down six Japanese planes for the loss of one of their own. They flew back to Kallang halfway through the battle, hurriedly re-fuelled, then returned to it.[32] Air battles went on for the rest of the day, and by nightfall it was clear that with the few aircraft Percival had left, Kallang could no longer be used as a base. With his assent, the remaining eight flyable Hurricanes were withdrawn to Palembang, Sumatra, and Kallang merely became an advanced landing ground.[33] No Allied aircraft were seen again over Singapore; the Japanese had achieved complete air supremacy.[34]

On the evening of 10 February, General Archibald Wavell ordered the transfer of all remaining Allied air force personnel to the Dutch East Indies. By this time, Kallang Airfield was so pitted with bomb craters that it was no longer usable.[26]

Second day

Believing that further landings would occur in the northeast, Percival did not reinforce the 22nd Brigade. On 9 February, the Japanese landings shifted to the southwest, where they encountered the 44th Indian Infantry Brigade. Allied units were forced to retreat further east. Bennett decided to form a secondary defensive line, known as the "Jurong Line", around Bulim, east of Tengah Airfield and just north of Jurong.

Brigadier Duncan Maxwell's Australian 27th Brigade, to the north, did not face Japanese assaults until the Imperial Guards landed at 22:00 on 9 February. This operation went very badly for the Japanese, who suffered severe casualties from Australian mortars and machine guns, and from burning oil which had been sluiced into the water. A small number of Guards reached the shore and maintained a tenuous beachhead.

Command and control problems caused further cracks in the Allied defence. Maxwell was aware that the 22nd Brigade was under increasing pressure, but was unable to contact Taylor and was wary of encirclement. In spite of his brigade's success, and in contravention of orders from Bennett, Maxwell ordered it to withdraw from Kranji in the central north. The Allies thereby lost control of the beaches adjoining the west side of the causeway.

Japanese breakthrough

The opening at Kranji made it possible for Imperial Guards armoured units to land there unopposed. Tanks with buoyancy aids attached were towed across the strait and advanced rapidly south, along Woodlands Road. This allowed Yamashita to outflank the 22nd Brigade on the Jurong Line, as well as bypassing the 11th Indian Division at the naval base. However, the Imperial Guards failed to seize an opportunity to advance into the city centre itself.

On the evening of 10 February, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, cabled Wavell, saying:

I think you ought to realise the way we view the situation in Singapore. It was reported to Cabinet by the C.I.G.S. [Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Alan Brooke] that Percival has over 100,000 [sic] men, of whom 33,000 are British and 17,000 Australian. It is doubtful whether the Japanese have as many in the whole Malay Peninsula... In these circumstances the defenders must greatly outnumber Japanese forces who have crossed the straits, and in a well-contested battle they should destroy them. There must at this stage be no thought of saving the troops or sparing the population. The battle must be fought to the bitter end at all costs. The 18th Division has a chance to make its name in history. Commanders and senior officers should die with their troops. The honour of the British Empire and of the British Army is at stake. I rely on you to show no mercy to weakness in any form. With the Russians fighting as they are and the Americans so stubborn at Luzon, the whole reputation of our country and our race is involved. It is expected that every unit will be brought into close contact with the enemy and fight it out ...[35]

Wavell subsequently told Percival that the ground forces were to fight on to the end, and that there should not be a general surrender in Singapore.[4]

My attack on Singapore was a bluff – a bluff that worked. I had 30,000 men and was outnumbered more than three to one. I knew that if I had to fight for long for Singapore, I would be beaten. That is why the surrender had to be at once. I was very frightened all the time that the British would discover our numerical weakness and lack of supplies and force me into disastrous street fighting.

On 11 February, concerned by the prospect of being dragged into fighting in built-up areas, Yamashita called on Percival to "give up this meaningless and desperate resistance". By this stage, the fighting strength of the 22nd Brigade—which had borne the brunt of the Japanese attacks—had been reduced to a few hundred men. The Japanese had captured the Bukit Timah area, including most of the Allied ammunition and fuel and giving them control of the main water supplies.

The next day, the Allied lines stabilised around a small area in the southeast of the island and fought off determined Japanese assaults. Other units—including the 1st Malaya Infantry Brigade—had joined in. A Malayan platoon—led by 2nd Lieutenant Adnan bin Saidi—held the Japanese for two days at the Battle of Pasir Panjang. His unit defended Bukit Chandu, an area which included a major Allied ammunition store. Adnan was executed by the Japanese after his unit was overrun.

On 13 February, with the Allies still losing ground, senior officers advised Percival to surrender in the interests of minimising civilian casualties. Percival refused, but unsuccessfully sought authority to surrender from his superiors.

That same day, military police executed a convicted British traitor, Captain Patrick Heenan, who had been an Air Liaison Officer with the British Indian Army.[37] Japanese military intelligence had recruited Heenan before the war, and he had used a radio to assist them in targeting Allied airfields in northern Malaya. He had been arrested on 10 December and court-martialled in January. Heenan was shot at Keppel Harbour, on the south side of Singapore, and his body was thrown into the sea.[4]

The following day, the remaining Allied units fought on. Civilian casualties mounted as one million people crowded into the area still held by the Allies and bombing and artillery fire increased. Civilian authorities began to fear that the water supply would give out.

Alexandra Hospital massacre

At about 13:00 on 14 February, Japanese soldiers advanced towards the Alexandra Barracks Hospital.[38] A British lieutenant—acting as an envoy with a white flag—approached the Japanese forces but was killed with a bayonet.[39] After the Japanese troops entered the hospital, a number of patients, including those undergoing surgery at the time, were killed along with doctors and members of nursing staff.[40] The following day about 200 male staff members and patients who had been assembled and bound the previous day,[41] many of them walking wounded, were ordered to walk about 400 m (440 yd) to an industrial area. Anyone who fell on the way was bayoneted. The men were forced into a series of small, badly ventilated rooms where they held overnight without water. Some died during the night as a result of their treatment.[42] The remainder were bayoneted the following morning.[43]

Private Haines of the Wiltshire Regiment—a survivor—had been in the hospital suffering from malaria. He wrote a four-page account of the massacre that was sold by his daughter by private auction in 2008;[44] Haines described how the Japanese did not consider those who were weak, wounded or who had surrendered to be worthy of life. After surrendering, staff were ordered to proceed down a corridor, where Sergeant Rogers was bayoneted twice in the back and another officer, Captain Parkinson, was bayoneted through the throat. Others killed included Captain Heevers and Private Lewis. Captain Smiley and Private Sutton were bayoneted but survived by playing dead. Many who had not been imprisoned in the tiny rooms in the industrial area were systematically taken away in small groups and bayoneted or macheted to death. This continued for 24 hours, leaving 320 men and one woman dead. Those who lost their lives included a corporal from the Loyal Regiment, who was impaled on the operating table, and even a Japanese prisoner who was perhaps mistaken for a Gurkha.

There were only five known survivors, including George Britton (1922–2009) of the East Surrey Regiment,[45] and Private Haines. Also Hugo Hughes, who lost his right leg, and George Wort, who lost an arm, both of the Royal Malay Regiment.[46] There may have been others. Haines' account came to light only after his death. Survivors were so traumatised that they rarely spoke of their ordeal.

After three days with no food or drink, those unable to walk were taken to Changi on wheelbarrows and carts, no motorised vehicles being available.

Fall of Singapore

By the morning of 15 February, the Japanese had broken through the last line of defence; the Allies were running out of food and ammunition. The anti-aircraft guns had also run out of ammunition and were unable to disrupt Japanese air attacks which were causing heavy casualties in the city centre. Looting and desertion by Allied troops further added to the chaos in this area.[47] Private Duncan Ferguson of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, claims Australian deserters were pushing women off the gangways to get aboard the departing ships evacuating the civilians[25] and other witnesses reported that many were drunk, raping the local Malay and Chinese women.[48] The Australian 8th Division had ceased to exist as an effective fighting formation between 10 and 12 February due to desertions.[49] At 09:30, Percival held a conference at Fort Canning with his senior commanders. He proposed two options: either launch an immediate counter-attack to regain the reservoirs and the military food depots in the Bukit Timah region and drive the enemy's artillery off its commanding heights outside the town; or capitulate. After heated argument and recrimination, all present agreed that no counterattack was possible. Percival opted for surrender.

A deputation was selected to go to the Japanese headquarters. It consisted of a senior staff officer, the colonial secretary and an interpreter. They set off in a motor car bearing a Union Jack and a white flag of truce toward the enemy lines to discuss a cessation of hostilities.[4] They returned with orders that Percival himself proceed with staff officers to the Ford Motor Factory, where Yamashita would lay down the terms of surrender. A further requirement was that the Japanese Rising Sun Flag be hoisted over the tallest building in Singapore, as soon as possible to maximise the psychological impact of the official surrender. Percival formally surrendered shortly after 17:15.

The terms of the surrender included:

- The unconditional surrender of all military forces (Army, Navy and Air Force) in Singapore.

- Hostilities to cease at 20:30 that evening.

- All troops to remain in position until further orders.

- All weapons, military equipment, ships, planes and secret documents to be handed over intact.

- To prevent looting, etc., during the temporary withdrawal of all armed forces in Singapore, a force of 1,000 British armed men to take over until relieved by the Japanese.

Earlier that day Percival had issued orders to destroy before 16:00, all secret and technical equipment, ciphers, codes, secret documents and heavy guns. Yamashita accepted his assurance that no ships or planes remained in Singapore. According to Tokyo's Domei News Agency Yamashita also accepted full responsibility for the lives of British and Australian troops, as well as British civilians remaining in Singapore.

Bennett caused controversy when he handed command of the 8th Division to Brigadier Cecil Callaghan and—along with some of his staff officers—commandeered a small boat.[50] They eventually made their way back to Australia. 20,000 Australian soldiers are reported to have been captured.[51][52][53] Bennett blamed Percival and the Indian troops for the defeat, but Callaghan reluctantly agreed with Percival that the Australians were largely responsible through desertions.[54] The Kappe Report compiled by Colonel J.H. Thyer and Colonel C.H. Kappe, concedes that only two-thirds at most, of the available Australian troops manned the final perimeter.[55]

Aftermath

The Japanese occupation of Singapore started after the British surrender. Japanese newspapers triumphantly declared the victory as deciding the general situation of the war.[56] The city was renamed Syonan-to (Japanese: 昭南島 Shōnan-tō; literally: Southern Island gained in the age of Shōwa, or "Light of the South"). The Japanese sought vengeance against the Chinese and to eliminate anyone who held any anti-Japanese sentiments. The Japanese authorities were suspicious of the Chinese because of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and killed many in the Sook Ching massacre. The other ethnic groups of Singapore—such as the Malays and Indians—were not spared either. The residents would suffer great hardships under Japanese rule over the following three and a half years.

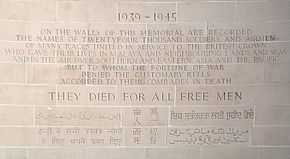

Numerous British and Australian soldiers taken prisoner remained in Singapore's Changi Prison. Many died in captivity. Thousands of others were shipped out on prisoner transports known as "hell ships" to other parts of Asia, including Japan, to be used as forced labour on projects such as the Siam–Burma Death Railway and Sandakan airfield in North Borneo. Many of those aboard the ships perished.

An Indian revolutionary Rash Behari Bose formed the Indian National Army with the help of the Japanese, who were highly successful in recruiting Indian soldiers taken prisoner.

In February 1942, from a total of about 40,000 Indian personnel in Singapore, about 30,000 joined the pro-independence Indian National Army, which fought Allied forces in the Burma Campaign as well as in the northeast Indian regions of Kohima and Imphal.[57] Others became POW camp guards at Changi. An unknown number were taken to Japanese-occupied areas in the South Pacific as forced labour. Many of them suffered severe hardships and brutality similar to that experienced by other prisoners of Japan during the war. About 6,000 survived until they were liberated by Australian and US forces in 1943–45.

After the Japanese surrender in 1945, Yamashita was tried by a US military commission for war crimes committed by Japanese personnel not under his command in the Philippines earlier that year, but not for crimes committed by his troops in Malaya or Singapore. He was convicted and hanged in the Philippines on 23 February 1946.[4]

See also

- Malaya Command

- British Far East Command

- Japanese order of battle during the Malayan Campaign

- British Military Hospital, Singapore

Notes

- ↑ Elphick in Singapore the impregnable fortress reports a quite different version.nflict = Battle of Singapore | image = [[File:Surrender Singapore.jpg|border|325px]] | caption = Lieutenant-General [[Arthur Percival]], led by a Japanese officer, walks under a [[flag of truce]] to negotiate the capitulation of Allied forces in [[Singapore in the Straits Settlements|Singapore]], on 15 February 1942. It was the largest surrender of British-led forces in history. | partof = the [[Pacific War]] and [[World War II]] | date = 8–1Elphick 1995, p. .

- ↑ Elphick claims that this was mainly due to the high level of desertion among Australian units.= Battle of Singapore | image = [[File:Surrender Singapore.jpg|border|325px]] | caption = Lieutenant-General [[Arthur Percival]], led by a Japanese officer, walks under a [[flag of truce]] to negotiate the capitulation of Allied forces in [[Singapore in the Straits Settlements|Singapore]], on 15 February 1942. It was the largest surrender of British-led forces in history. | partof = the [[Pacific War]] and [[World War II]] | date = 8–15 FebruaryElphick 1995, p. .

Citations

- ↑ L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Rear-Admiral Shoji Nishimura". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Unlike Dunkirk, there was no 'miraculous' evacuation at Singapore and 100,000 British, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops were captured when it fell on 15 February 1942, Britain's blackest day of the war. Britain in the Twentieth Century, William B. Hopkins, Page 208, Routledge, 21 Aug 2013

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The loss of Malaya and the seemingly impregnable fortress island of Singapore in a campaign lasting a little over two months, which also resulted in the capture of over 120,000 British and imperial troops, has been seen as a lasting stain on British military history. How Fighting Ends: A History of Surrender, Holger Afflerbach, Hew Strachan, Page 341, Oxford University Press, 26 Jul 2012

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Smith, Colin (2006). Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II. Penguin Group. ISBN 0-14-101036-3.

- ↑ Churchill, Winston (1986). The Hinge of Fate, Volume 4

- ↑ The day the empire died in shame

- ↑ Thompson, p. 92–94.

- ↑ L, Klemen; Bert Kossen, Pierre-Emmanuel Bernaudin, Dr. Leo Niehorster, Akira Takizawa, Sean Carr, Jim Broshot, Nowfel Leulliot (1999–2000). "Seventy minutes before Pearl Harbor – The landing at Kota Bharu, Malaya, on December 7th 1941". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- ↑ Video on YouTube

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ (The Jungle, Japanese And The British Commonwealth Armies At War, 1941-45, Page 34.)

- ↑

- ↑ Thompson, p. 103–130.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 60–61.

- ↑ "The Malayan Campaign 1941". Archived from the original on 19 November 2005. Retrieved 7 December 2005.

- ↑ Lee, Singapore: The Unexpected Nation, pg 37

- ↑ War for the Empire: Malaya and Singapore, Dec 1941 to Feb 1942, Richard Reid, Australia-Japan Research Project

- ↑ "Maxwell made it worse by pulling his own brigade back without orders, losing touch with it, then allowing it to be split in two". Between 2 Oceans (2nd Edn): A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971, p. 358, Malcolm H. Murfett, John Miksic, Brian Farell, Chiang Ming Shun, Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pty Ltd, 2011

- ↑ "Maxwell should have been court-martialled for defeatism. As early as late January Bennett had reprimanded him repeatedly for complaining about the situation and his tired troops, warning to stop "wet nursing" his soldiers. Instead of removing this dangerous influence, Bennett left him in command". Between 2 Oceans (2nd Edn): A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971, p. 350, Malcolm H. Murfett, John Miksic, Brian Farell, Chiang Ming Shun, Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pty Ltd, 2011

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 4C Special: No Prisoners

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Frank Owen (2001). The Fall of Singapore. England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-139133-2.

- ↑ Reagan, Geoffrey. Military Anecdotes (1992) p. 189, Guiness Publishing ISBN 0-85112-519-0

- ↑ "While most of his squadron went on to Singapore, Davis and sixty of his men left the train at the town of Seletar so that they could drive over to Kuantan and meet their aircraft. They were within about 25 miles of their destination when they met up with a convoy of trucks packed with ground crew. Most of them were from 8 Squadron, the other RAAF Hudson unit. They informed the astonished wing commander that Kuantan had been bombed for the first time that morning and that, as a result, all the aircraft had left for Singapore. They were on their way to join them". Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II, p. ?, Colin Smith, Penguin, 2006

- ↑ "All agree the ground crew left without completing the vital task of denial, leaving runways usable and large stocks of petrol and bombs intact". The Defence and Fall of Singapore 1940-1942, Brian Padair Farrell, p. 143, Tempus, 2005

- ↑ "Huge stocks of bombs and large supplies of petrol were abandoned at Kota Bahru and the runways had not been cratered ... According to the Official Historian, 'The hurried evacuatin of the airfield at Kota Bahru was premature and not warranted by the ground situation.' No offensive or reconnaissance aircrarft were now available at Kota Bahru, and the Battle of Kelantan was as good as lost". The Battle for Singapore: The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II, Peter Thompson, p. ?, Hachette, 2010

- ↑ Cull, Brian and Sortehaug, Brian and Paul. Hurricanes Over Singapore: RAF, RNZAF and NEI Fighters in Action Against the Japanese Over the Island and the Netherlands East Indies, 1942. London: Grub Street, 2004. (ISBN 1-904010-80-6), pp. 27–29. Note: 64 Sentai lost three Ki-43s and claimed five Hurricanes.

- ↑ "Hawker Hurricane shot down on 8 February 1942". Archived from the original on 30 July 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ↑ Captured Hurricane, Captured J-Aircraft

- ↑ Percival's Despatches

- ↑ The Second World War. Vol. IV. By Winston Churchill.

- ↑ Shores 1992, p. 383.

- ↑ Peter Elphick, 2001, "Cover-ups and the Singapore Traitor Affair" Access date: 5 March 2007.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 476.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 477.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 476–478.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 477–478.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 478.

- ↑ "Alexandra Massacre". Archived from the original on 18 October 2005. Retrieved 7 December 2005.

- ↑ Daily Express, 14 August 2008

- ↑ George Britton, personal recollection 2009

- ↑ Hugo Hughes' war diary, written in Changi

- ↑ Nicholas Rowe, Alistair Irwin (21 September 2009). "Generals At War". 60 minutes in. National Geographic Channel. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ 'The greater part of the Australian infantry were undisciplined,' observed Bradell, who say swarms of deserters, many drunk, struggling to get on to the ships that would take them away. Other witnesses reported Australians bullying their way on to boats, looting and raping Malay and Chinese women. These reports were read by Churchill and then withheld from public scrutiny for fifty years, no doubt to satisfy Australian sensibilities. Churchill and Empire, Lawrence James, p.?, Hachette, 2013

- ↑ "Nevertheless, the division did indeed fall apart in the end because it did not bring the straggler problem under control. From 10 through 12 February mass straggling turned into mass desertion, and only a rump formation fought in the final perimeter". Between 2 Oceans (2nd Edn): A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971, p. 356, Malcolm H. Murfett, John Miksic, Brian Farell, Chiang Ming Shun, Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pty Ltd, 2011

- ↑ Lieutenant General Henry Gordon Bennett, CB, CMG, DSO an Australian War Memorial article

- ↑ The fall of Singapore saw the loss of more than 20,000 highly trained volunteers of the Australian Imperial Force, when most of Australia's 8th Division was taken prisoner of war in Malaya. The Pacific War: The Strategy, Politics, and Players that Won the War, William B. Hopkins, Page 96, Zenith Press, 12 Jan 2009

- ↑ Return to the Thai-Burma Railway

- ↑ 22nd Brigade Headquarters Association

- ↑ "Bennett singled out Indian troops but did not confine his remarks to them. He admitted that towards the end it was all but impossible to return men to their units ... Callaghan recommended that on any clash Percival's report be accepted as more reliable ... Regarding the many reports of Australians hiding in town or trying to escape, Callaghan bluntly admitted "there is a certain amount of truth in both these statements ... This temporary lapse of the Australian on the island and the criticism it has invoked has caused me a lot of uneasiness"". Between 2 Oceans (2nd Edn): A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971, p. 360, Malcolm H. Murfett, John Miksic, Brian Farell, Chiang Ming Shun, Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pty Ltd, 2011

- ↑ "The authors took every chance to excuse the troops' performance by bringing up other considerations, an indication of how sensitive the issue was. But in the end they admitted only two-thirds at most of those fit to fight manned the final perimeter". Between 2 Oceans (2nd Edn): A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971, p. 360, Malcolm H. Murfett, John Miksic, Brian Farell, Chiang Ming Shun, Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pty Ltd, 2011

- ↑ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945 p 277 Random House New York 1970

- ↑ Stanley, Peter. ""Great in adversity": Indian prisoners of war in New Guinea". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 14 January 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

References

- Cull, Brian (2004). Hurricanes Over Singapore: RAF, RNZAF and NEI Fighters in Action Against the Japanese Over the Island and the Netherlands East Indies, 1942. Grub Street Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904010-80-7.

- Cull, Brian (2008). Buffaloes over Singapore: RAF, RAAF, RNZAF and Dutch Brewster Fighters in Action Over Malaya and the East Indies 1941–1942. Grub Street Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904010-32-6.

- Dixon, Norman F. On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, London, 1976

- Bose, Romen. SECRETS OF THE BATTLEBOX: The History and Role of Britain's Command HQ during the Malayan Campaign, Marshall Cavendish, Singapore 2005

- Bose, Romen. KRANJI:The Commonwealth War Cemetery and the Politics of the Dead, Singapore: Marshall Cavendish (2006)

- Elphick, Peter, Singapore, the pregnable fortress, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1995, ISBN 0-340-64990-9

- Kelly, Terence (2008). Hurricanes Versus Zeros: Air Battles over Singapore, Sumatra and Java. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-622-1.

- Kinvig, Clifford. Scapegoat: General Percival of Singapore, London (1996) ISBN 0-241-10583-8

- Leasor, James. Singapore: The Battle That Changed The World UK, USA 1968, 2011. ISBN 978-1-908291-18-9

- Percival, Lieutenant-General A.E. (1946). Operations of Malaya Command from 5th December 1941 to 15th February 1942. London: UK Secretary of State for War. (Percival's despatches published in The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 38215. pp. 1245–1346. 20 February 1948. Retrieved 16 August 2012.)

- Seki, Eiji. Mrs. Ferguson's Tea-Set, Japan and the Second World War: The Global Consequences Following Germany's Sinking of the SS Automedon in 1940. London: Global Oriental (2006) ISBN 1-905246-28-5; (cloth) [reprinted by University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2007 – previously announced as Sinking of the SS Automedon and the Role of the Japanese Navy: A New Interpretation.]

- Shores, Christopher F; Cull, Brian; Izawa, Yasuho. Bloody Shambles: The First Comprehensive Account of the Air Operations over South-East Asia December 1941 – April 1942, London: Grub Street (2007)

- Shores, Christopher F; Cull, Brian; Izawa, Yasuho. Bloody Shambles, The First Comprehensive Account of the Air Operations over South-East Asia December 1941 – April 1942 Volume One: Drift to War to the Fall of Singapore. London: Grub Street Press. (1992) ISBN 0-948817-50-X

- Smith, Colin. Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II Penguin (2005) ISBN 0-670-91341-3

- Smyth, John George, Percival and the Tragedy of Singapore, MacDonald and Company, 1971

- Thompson, P. The Battle for Singapore, The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II, London (2006) ISBN 0-7499-5099-4

External links

| Library resources about Battle of Singapore |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Singapore. |

- National Heritage Board, Battlefield Singapore

- Bicycle Blitzkrieg – The Japanese Conquest of Malaya and Singapore 1941–1942

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and the Second World War – the Far East

- The diary of one British POW, Frederick George Pye of the Royal Engineers. Fred Pye was a POW for 3½ years, including time spent building the Burma Railway. He managed to save, write on and bury scraps of paper, and after the war compiled them into a readable form.

- Animated History of the Fall of Malaya and Singapore