Battle of Oberwald

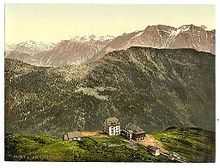

Battle of Oberwald occurred on 13–14 August 1799 between French forces commanded by General of Division Jean Victor Tharreau and elements of Prince Rohan's corps in southern Switzerland. The Austrian regiment was commanded by Colonel Gottfried von Strauch. Both sides engaged approximately 6,000 men. The French lost 500 killed, wounded or missing, and the Austrians lost 3,000 men and two guns.[1] Oberwald is a village in Canton Valais, at the source of the Rhône River, between Grimsel and Furka passes.[2]

Background

Within six months of signing the Treaty of Campo Formio (October 1797), the French Directory had established a new modus operandi to expand its area of influence. The Republic sought a contiguous territory between France and the Holy Roman Empire. To accomplish this, France subverted Austrian and Imperial influence by exporting its own brand of revolution to former Austrian territories in the Lowlands, creating the Batavian Republic. By lending French military muscle, local collaborators seized power and established other satellite republics. In several of the Italian states that bordered on France, Switzerland, and Austria, they created the Cisalpine and Ligurian Republics, which included most of Genoa and much of the Savoyan territories. In December 1798, the King of Sardinia, was forced to abdicate and the Piedmont was occupied and "republicanized;" Sardinia had already been forced into a treaty with France that gave the French army free passage through the Piedmont. In 1798, Switzerland was restructured into the Helvetic Republic, modeled on revolutionary France; the traditional mode of self-governing cantons was deemed as feudal by modern revolutionary ideals.

These newly formed republics served multiple purposes: they were a nursery for soldiers to learn the craft of warfare; they functioned as a proving ground for military leadership, a continuation of what Ramsey Weston Phipps has called "The School for Marshals";[3] and, finally, they gave France a formidable strategic position with friendly buffer states that stretched from the Adriatic to the North Sea.[4]

Valais insurgency

On 24 May 1799, several thousand insurgents, reinforced with French deserters, recruits from some of the minor cantons, some Austrian battalions, and emboldened with the news of approaching Russian forces, emerged from the wood at Finge and attacked a French encampment. The French, under command of Charles Antoine Xaintrailles, beat them off and they withdrew to their own entrenchments. Before daybreak on the following morning (25 May), Xaintrailles attacked in two columns. The first, Column Barbier (three battalions and one squadron), drove the insurgents out of the woods and chased them to the Leuk. The second, the left column, including two battalions of the 89th and 110th as well as some of the grenadiers of those two demi-brigades, were under the personal command of Xaintrailles, and attacked the insurgent position at Leuk, defended by seven guns so carefully placed as to deliver enfilade fire on the passage of the valley; furthermore, the insurgents had placed sharpshooters on the approaches to the gorge. Xaintrailles sent two flanking detachments to the crest of the mountains, well out of artillery range, while the main body in the valley attacked the position in front of them. It received such a storm of musketry and canister fire at the foot of the entrenchments that it began to waver; at this point, a well-sustained fusilade from the crest of the mountains showered the insurgents' flanks. The men in the gorge redoubled their efforts and entered the Valais entrenchments, slaying some of the gunners at their positions. The survivors fled to Raron, abandoning their guns and magazines.[5]

On 26 May, Xaintrailles' right column crossed the Saltina river via a ford and marched to Brig, where some of the insurgents had rallied. These abandoned the town and fled into the mountains behind it. The left column, column Xaintrailles, reached Naters on the right bank of the Rhone and proceeded to Mörel and Lax, seeking to capture the bridge between Lax and Ernen, where the largest group of the insurgents had congregated. While he was reforming his troops, he offered the insurgents an olive branch: if they would lay down their arms and return to their homes, he promised an amnesty for the past. Those who persisted in revolt would face summary execution. A number of the insurgents did submit, but many withdrew to Lax where, reinforced by a couple of Austrian battalions, they rejected all offers of amnesty and placed their reliance on nature's formidable position. There followed a day-long battle with alternating results; eventually, the insurgents were routed, but the contest was maintained by those two Austrian battalions, who eventually abandoned the field as night fell, and light failed. Xaintrailles pushed on with the grenadiers of the 100th and sent several companies of the 100th to St. Bernard. His Swiss allies guarded the gorges and defiles behind him. He established his headquarters at Brig, from which he could control the passes at Great St. Bernard and Simplon and access to northern Italy, and awaited his instructions from Massena.[6]

Coalition resurgence

After the Swiss uprisings of 1798, the Austrians had stationed troops in the Grisons, at the request of the Canton, which had not joined the new Helvetic Republic under the protection of the French Directory. In March 1799, war had again broken out between the Austrians and its coalition allies against the French. Massena, who commanded the French army in Switzerland, surprised the Austrian division stationed in the Grisons, though, and overran the countryside. To the north, after victories at Ostrach and Stockach, and later at Feldkirch, the Archduke Charles pushed the French out. The Swiss general Hotze, in Austrian service, approached through the Grisons, and following a successful engagement at Winterthur. The Austrians, following up on their success, over ran most of eastern Switzerland. Massena left Zurich and fell back to the River Reuss.[7]

The smaller cantons took this opportunity to extract themselves from the French alliances: Uri took possession of the pass at St. Gothard, and the people of Upper Valais occupied the Simplon pass. Schwyz, one of the original medieval establishments, also rebelled. However in May, the French returned in greater numbers; Charles Xaintrailles, circling south of Massena's main force at the Reuss headwaters at Hospental, had been directed to attack and subdue the rebellions in the St. Valais. Although Russian and Austrians occupied Zurich, the headquarters of the Allies, the French evacuated Schwyz and assumed positions on the frontiers of Zug by Arth. The Austrians entered Schwyz, where the inhabitants welcomed them joyously. On 3 July, the French attacked the whole Austrian line there, but the Austrians, with strong support of the Schwyz people, repulsed them again.[8] By the end of July, Switzerland was occupied by 75,941 French troops and 77,912 Austrians. The French line ran from Hüningen, in the Elsass at the border of Switzerland, Baden, and France, over the Albis (a chain of mountains near Zurich) through the Four Forest cantons, in Hasletal, and to the foot of the Simplon pass and the St. Berhard's pass. It was strongest in front of the Wiese, and by Wutach, and enclosed a line from the Limmat to Lake Lucerne, and ended by Graubunden.[9]

Battle

Disposition

After routing the Austrians and Valaisians from the field in early June, Xaintrailles concluded that he did not have sufficient troops to pursue Strauch into the mountains. He gathered his forces, including the 28th and 104th regiments, which had reached Vevey, to join him in Brieg and awaited instructions from Massena. Hadik, commanding the Austrian/Russian force, moved Strauch to Oberwald to support the Valaisans, and sent General Rohan to Domo d'Ossola. The French goal, eventually, was to retake the Simplon and St. Gothard passes. The narrowness of the valleys did not permit the normal concentration of troops.[10]

On 13 August, Lecourbe's command included the 84th Demi-brigade (Brigade Boivin), and the 76th Brigade (Loison); this amounted to close to 12,000 men. Chabran's division stood in the Aegerisee and the Sihl valleys; it moved in two coloumns against the troops of Jellacic. On 13 August, all French troops in the Valais set out at once, and by the 14th they were in movement on all points from the Rhône to Zurich.[10]

Aftermath

The Aulic Council, in its wisdom, ordered Archduke Charles to move most of his force into Swabia, to continue his operations on the north side of the Rhine and Massena attacked the Russians in Zurich who, weakened by the losses of the Austrian troops and poorly commanded, lost the city to him in September 1799. By that time, also, the French had wrested control of the mountain passes at Simplon and St. Bernard back from the Austrians, and controlled access and egress between Switzerland and northern Italy.[11]

The losses of local people were catastrophic. By the end of the French campaign in Schwyz and Valais, one fourth of the population of the Canton Schwyz depended on public charity for support. In the Muotta valley, between 600–700 people were reduced to utter destitution. In Uri, a relatively poor canton, comparable distress reigned; a fire broke out at Altdorf which destroyed the greater part of that town, the main city of the canton. In Unterwalden, which had been devastated in 1798, similar situations prevailed. In the Grisons, where the uprising had been quelled in 1798, 3,000 inhabitants had been killed and the abbey of Disentis burned. In a remote valley of Tavetsch, all the inhabitants were killed; four women, hunted by the soldiers threw themselves into the lake of Toma, with infants in arms, and were shot and killed in the half-frozen water.[12]

Notes and citations

Notes

- ↑ Gottfried von Strauch, Freiherr, Feldzeugmeister and Inhaber of Galician Infantry Regiment Nr. 24 (appointed 1808), died in Vienna 18 March 1836. Militär-Schematismus des österreichischen Kaiserthums. Aus der k.k. Hof- und Staats-Druckerei., 1837 p.148, 513.

- ↑ The Brigade Strauch included 1 Batallion Banat regiment (976),2 Battalion of Wallis (1701), 1 Battalion Granadier Weissenwolf (1714), 6 copnies Regiment Siegenfeld (683), six companies Carneville (392), and 1 Squadron of Erdody Hussars (174), See Reinhold Günther, Der Feldzug der Division Lecourbe in Schweizerischen Hochgebirge 1799, Switzerland, J. Huber, 1896p. 96.

Citations

- ↑ Digby Smith, Napoleonic Wars Data Book, CH:Oberwald. Greenhill Press, 1978, p. 162.

- ↑ (German) Bodart, Gaston. Militär-historisches kreigs-lexikon, (1618–1905). Vienna, Stern, 1908, p. 340.

- ↑ Ramsey Weston Phipps,

- ↑ Timothy Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787-1802, pp. 227-228.

- ↑ Shadwell, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Shadwell, p. 95.

- ↑ Andre Veusseux, The History of Switzerland. Society for the diffusion of useful knowledge, 1840, p. 244-245.

- ↑ Veusseux, pp. 244–245.

- ↑ (German) Reinhold Günther, Der Feldzug der Division Lecourbe im Schweizerischen Hochgebirge 1799. Switzerland, J. Huber, 1896, reprinted by Nabu public domain reprints, 2013, p. 109.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Shadwell, p. 149.

- ↑ Blanning, 231.

- ↑ Vieusseux, pp. 245–246.

Sources

- Blanning, Timothy Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787-1802.

- (German) Bodart, Gaston. Militär-historisches kreigs-lexikon, (1618–1905). Vienna, Stern, 1908, p. 340.* Militär-Schematismus des österreichischen Kaiserthums. Aus der k.k. Hof- und Staats-Druckerei., 1837 pp. 148, 513.

- Smith, Digby., Napoleonic Wars Data Book, London, Greenhill Press, 1978.

- Veusseux, Andre. The History of Switzerland. Society for the diffusion of useful knowledge, 1840.