Battle of Malvern Hill

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

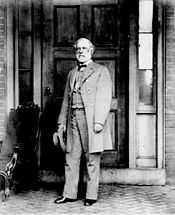

At the Battle of Malvern Hill (July 1, 1862) during the American Civil War, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under the command of General Robert E. Lee and the Union Army of the Potomac under General George B. McClellan clashed near Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. Also known as the Battle of Poindexter's Farm, it involved over fifty thousand soldiers from each side, hundreds of pieces of artillery and three warships. The battle was part of the Peninsula Campaign's Seven Days Battles.

McClellan had an ambitious plan to begin his Peninsula Campaign and eventually take Richmond: sail around the rebels, and land his Army of the Potomac at the tip of the peninsula. The plan was successful; fierce fighting ensued. Confederate commander-in-chief Joseph E. Johnston fended off McClellan's repeated attempts to take the city. After Johnston was wounded, Lee took command and launched a series of counterattacks, collectively called the Seven Days Battles, culminating in the action on Malvern Hill.

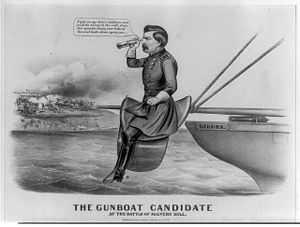

The Union V Corps, under Fitz John Porter, took up positions on the hill on June 30 in preparation for the battle, which began the following day. McClellan himself was not present for the beginning of the battle, having boarded the ironclad USS Galena and sailed downriver. Confederate preparations were hindered by several mishaps. Bad maps and faulty guides caused Confederate general John Magruder to be late for the battle, an excess of caution delayed Benjamin Huger and Stonewall Jackson had problems collecting the Confederate artillery. Nonetheless, the Confederates attacked first, when the artillery on the left flank began firing upon the Union line. The Federal artillery, however, was the story of the day, repulsing attack after attack.

In the aftermath of the battle, the Confederate press heralded Lee as the savior of Richmond. McClellan was criticized harshly for his absence from the battlefield, an issue that haunted him when he ran for president in 1864. From Malvern Hill, McClellan and his forces withdrew to Harrison's Landing where he would stay until August 16. Lee withdrew to Richmond to prepare for his next operation, as the action on Malvern Hill ended the campaign on the Peninsula.

Background

Military situation

In spring 1862, Union commander George McClellan developed an ambitious plan to capture Richmond, the Confederate capital, and the Virginian Peninsula: his 121,500-man Army of the Potomac, along with 14,592 animals, 1,224 wagons and ambulances, and 44 artillery batteries, would load onto 389 vessels and sail to the tip of the peninsula at Fort Monroe, then move inland and capture the capital.[1] The grandiose landing, having "the stride of a giant", was executed with few incidents.[2] Afterwards, the Peninsula Campaign slowed to a crawl, much to the chagrin of those in Washington, especially President Abraham Lincoln. On May 26, 1862, several months after the campaign's advent, Lincoln wrote McClellan, saying, "What impression have you, as to intrenchments [sic]—works—for you to contend with in front of Richmond [Virginia]? Can you get near enough to throw shells into the city?"[3] Soon after, McClellan's army took up positions so close to Richmond, they "could see the church spires of the city".[4] By May 30, he had begun moving troops across the Chickahominy River, the only major natural barrier that separated him and his army from Richmond.[5]

On May 31, roughly half of McClellan's Army of the Potomac still remained on the south banks of the Chickahominy—likely due to a violent thunderstorm the night before that spiked the water level and consumed two bridges. Confederate general-in-chief Joseph E. Johnston, who sought to capitalize on the bifurcation of McClellan's army, led three columns of soldiers to attack that day in what would be known as the Battle of Seven Pines. Johnston's plan fell apart, and McClellan lost no ground. That evening, as the battle was drawing to a close, Johnston was hit in the right shoulder by a bullet and in the chest by a shell fragment; his command went to Major General Gustavus W. Smith. Smith's tenure as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia was short; on June 1, after an unsuccessful attack on Union forces, Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy, appointed General Robert E. Lee, his own military adviser, to replace Smith as the commander-in-chief of the Confederate armies. Lee immediately ordered a withdrawal to Richmond and, by that evening, both McClellan's Army of the Potomac and Lee's Army of Northern Virginia were in their original positions—the former at the south Chickahominy and the latter in Richmond. For the next two weeks, McClellan harangued Washington for more troops, as he felt Lee's army "heavily outnumbered" his own.[lower-alpha 1] Meanwhile, Lee began strengthening Richmond's trenches, and reconnoitered McClellan's position, authorizing Brigadier General J.E.B. Stuart's "Ride Around McClellan" on June 12.[6]

On June 25, Lee was leading his 60,000-man Army of Northern Virginia to fight the next day when McClellan preempted him in a surprise attack at Oak Grove. Lee's men successfully warded off the Union assault and the surprise did not hamper his plans. The next morning, the Confederates crossed the Chickahominy and attacked McClellan in the Battle of Mechanicsville. Union forces turned back the Confederate onslaught, inflicting heavy losses. After Mechanicsville, McClellan's forces drew back to a position behind Boatswain's Swamp. There, on June 27, his army again attacked, this time at Gaines's Mill. The resulting battle was the only clear Confederate victory during the Seven Days. While the sun shone, some of Lee's men had launched successive attacks over rough, muddy terrain against the Union line, all to no avail. Then, as the sun set, a final concerted attack broke the Union line and the Confederates carried the day. Each side suffered over six thousand casualties. The action at Garnett's and Golding's Farm, fought next, was merely a set of skirmishes. On June 29, Lee attacked McClellan in the Battle of Savage's Station, but once again, to no avail. The battle's execution was uncoordinated, allowing the Federals to escape. Lee was undeterred; on June 30, he renewed his offensive on the Union Army in the battles of Glendale and White Oak Swamp, but the results of both battles were inconclusive. This series of aggressions came to be a part of the Seven Days Battles in which both Lee and McClellan suffered heavy casualties. Nevertheless, on June 30, McClellan's forces began to accumulate atop Malvern Hill, an imposing natural position, inviting battle. Lee obliged.[8]

Geography and location

It was as beautiful a country as my eyes ever beheld. The cultivated fields, interspersed with belts & clusters of timber & dotted with delightful residences, extended several miles. The hills were quite high, but the slopes gradual & free from abruptness. Wheat was in the shock, oats were ready for the harvest, & corn was waist high. All were of most luxuriant growth.[9]

Malvern Hill, a plateau-like elevation in Henrico County, Virginia and the namesake of the battle, provided for an impressive natural military position. The hill rose some 100 to 130 feet (30 to 40 m)[9][10] to its crest and was about two miles (3.2 km) from the James River.[11] It formed a crescent of about 1.5 miles (2.4 km)[10] length and 0.75 miles (1.21 km)[9] width. The Malvern Cliffs, a bluff-like formation, comprised the western side of the hill and overlooked Turkey Run, a tributary of nearby Turkey Island Creek. Western Run was another tributary of Turkey Island Creek, which lay mostly along the eastern side of the hill and slanted into the northern side slightly. Malvern Hill's center was at a slightly decreased elevation than the flanks and the slope was about one mile (1.6 kilometers) in length and very gradual, with only one or two notable depressions, one of which dipped some sixty feet (18 meters) at the valley of Western Run and slanted upwards to the plateau. The gentle, bare slant meant that any assailing army could not easily take cover, and artillery would have the benefit of a clear, open field.[9][12]

Several farms were positioned near Malvern Hill. Some 1,200 yards (1,100 m)[13] north of the hill were the Poindexter and Carter farms. Between the two farms was a swampy and thickly wooded area that made up the course of Western Run. The Crew family's farm, the largest in the area, was situated at the western side of the hill and about a quarter of a mile due east of Malvern Hill was the West farm. Between these two farms was the Quaker Road, which some locals called the Willis Church Road, for the Willis Methodist Church near it.[14] The Quaker Road also ran past the Malvern house, the hill's namesake, which was perched atop the southern edge of the plateau.[13]

McClellan's forces prepare

On the morning of June 30, 1862, the Union V Corps under Brigadier General Fitz John Porter, a part of McClellan's Army of the Potomac, amassing atop Malvern Hill. Colonel Henry Hunt, McClellan's skilled chief of artillery,[11] posted more than 100 guns on the hill's slope and 150 more in reserve at the rear of the hill near the Malvern house.[10] The artillery line on the hill's slope consisted of eight batteries of field artillery with thirty-seven guns.[15] Brigadier General George Sykes's division would guard the line. In reserve, additional field artillery and three batteries of heavy artillery included five 4.5-inch (11 cm) Rodman guns, five 20-pounder (9.1 kg) Parrott rifles and six 32-pounder (15 kg) howitzers.[16] As more of McClellan's forces arrived at the hill, General Porter continued to reinforce the Union line. Brigadier General George Morell's units, who were stationed between the Crew and West farms, extended the line to the northeastern section. Brigadier General Darius Couch's division of the IV Corps, as yet unbloodied by the skirmishes of the Seven Days, further extended the northeastern line. This left 17,800 soldiers from Couch's and Morell's division at the northern face of the hill, overlooking the Quaker Road from which Lee's forces were anticipated to attack.[15]

Throughout the course of June 30 and even into the night, tired soldiers ambled from the Quaker Road and onto Malvern Hill. "What the road was... I cannot recall," remarked Lieutenant Thomas Livermore of the 5th New Hampshire Infantry, "I know simply that it was darkness and toil, until we began climbing a hill and were greeted with advancing dawn."[17]

Early the next day, Tuesday, July 1, General McClellan rode the course of the battle line, to the roar of applause from his subordinates. McClellan was greatly heartened at the display, writing to his wife, "The dear fellows cheer me as of old as they march to certain death & I feel prouder of them than ever."[17] Upon inspection of the battle line, McClellan, who had recently come from nearby Haxall's Landing, held that he had "most cause to feel anxious about the right [flank]." The entire right (or eastern) flank was behind Western Run—an area necessary for the planned movement of his forces to Harrison's Landing—and McClellan feared an attack on that side. As a result, he posted the largest portion of his army there—two divisions from Edwin Sumner's II Corps, two divisions from Brigadier General Samuel P. Heintzelman's III Corps, two divisions from Brigadier General William Franklin's VI Corps and one division from Major General Erasmus Keyes's IV Corps, who were stationed across the James. The division of George McCall, badly damaged in the fighting at Glendale with McCall himself wounded and captured, would be held in general reserve.[18]

Despite saying that his army was "in no condition to fight without 24 hours rest" and praying Lee's forces "may not be in condition to disturb [them] today",[17] McClellan left his troops at Malvern Hill and traveled downstream aboard the ironclad USS Galena towards Harrison's Landing on the north bank of the James River. McClellan did not give the command of the troops to any person; however, Brigadier General Porter, who was in command during the initial attack, became the de facto commander on the Union side of the battle.[17]

Lee's forces advance

Early on the morning of the battle, Lee met with his lieutenants, including Major Generals James Longstreet, A. P. Hill, Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson and John Magruder, on the Long Bridge Road to plan the pursuit of Federal forces to Malvern Hill. As with McClellan, a group of troops noticed the generals and cheered. Lee gave a salute and continued his conversation.[19]

During their ride, Lee and his generals met Major General D.H. Hill. Hill's conversation with a chaplain from his command who was familiar with Malvern Hill impelled him to question the prudence of Lee's attack. Hill's fears were not unfounded. Malvern Hill's geography provided for an impressive, and if exploited well, an impregnable, military position. "If General McClellan is there in strength," cautioned Hill, "we had better let him alone."[20] Longstreet did not share Hill's objections, laughing off his caution and saying, "Don't get so scared, now that we've got him [General McClellan] whipped."[21] Lee himself had noted the "great natural strength" possessed by Malvern Hill, and spent a considerable amount of time preparing for the approaching battle.[22]

Lee chose the relatively well-rested units of D.H. Hill, Stonewall Jackson and John Magruder to lead the Confederate offensive, as they had barely participated in the fighting of the day before. Meanwhile, James Longstreet's and A.P. Hill's division would be held in reserve, as they had fought the majority of the previous day's hostilities.[23] Two brigades under Stonewall Jackson, the commands of Major General Richard Ewell and Brigadier General William H.C. Whiting, would also be kept in reserve.[23]

According to Lee's plan, the Army of Northern Virginia would form a semi-circle enveloping Malvern Hill. D.H. Hill's five brigades would be placed along the northern face of the hill, forming the center of the Confederate line, and the divisions of Stonewall Jackson and John Magruder would man the left and right flanks, respectively. Brigadier General Whiting's forces would position themselves on the Poindexter farm, with the outfits of Brigadier General Charles Sidney Winder and Richard Ewell nearby. The infantry of these three detachments would provide reinforcement for the Confederate line if necessary.[24] Major General Theophilus Holmes would take up a position on the extreme Confederate right flank.[20]

Batteries have been established to rake the enemies' line. If broken as is probable, [Brigadier General Lewis] Armistead, who can witness the effect of the fire, has been ordered to charge with a yell. Do the same.

Lee made his field headquarters at a blacksmith's shop, where he surveyed the left flank himself for possible artillery positions. After a reconnoitering expedition on the right flank, James Longstreet returned to Lee and the two compared their results and concluded that two grand battery-like positions would be established at the left and right sides of Malvern Hill. The artillery fire from the batteries was supposed to, as Longstreet put it, "so discomfit them as to warrant an assault by infantry."[25] An infantry assault by McClellan's forces would open up the Union line, allowing Lee's soldiers to break through and attack. If this plan did not work out, Lee and Longstreet felt the artillery fire would give them enough of a chance to reconsider.[24]

With a battle plan in order, Lee sent a draft to his lieutenants, written by his chief of staff, Colonel Robert Chilton. (see right box). Unfortunately, the instructions left the only signal of attack for fifteen brigades as the yell of a single charging brigade. Amid the rigors and noises of battle, this was bound to create confusion.[25]

Battle

Key participants

| Commanders in the Battle of Malvern Hill | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Preliminary goals and strengths of forces

Estimates of the troop strengths McClellan and Lee had at Malvern Hill vary widely,[22][23] with different sources reporting from 54,000[22] to 80,000[23] troops for the Union side, and 55,000[22] to 80,000[23] for the Confederate side.

McClellan's goal was simple: retreat. McClellan felt that the Confederate armies outnumbered his own and feared his army's destruction.[26] Furthermore, John Rodgers of the United States Navy had informed McClellan that he could not guarantee the safety of the Army of the Potomac's supplies beyond the Landing.[27] Thus, on the night of June 28, after the second day of action at the Garnett's of Golding's farm, McClellan decided to retreat to the safety of Harrison's Landing. "The commanding general announced to us his purpose to begin a movement to the James River on the next day," said Union general William B. Franklin.[28] In fact, McClellan was at Harrison's Landing for the beginning of the Battle of Malvern Hill, inspecting his army's future embarkation point there.[29]

Lee's goal was somewhat more complex. McClellan's army was evidently on the run. This view was corroborated by the many abandoned commissary stores, wagons and arms. He saw the hundreds of Union stragglers and deserters his units had happened upon and captured as a sign of demoralization in McClellan's army. A final decisive attack would destroy McClellan's army, Lee thought. In five days of offensives, Lee's plans and strategies had fallen apart. His chances to fulfil his desire to destroy McClellan's army were diminishing quickly. All these factors played into the decisions Lee made during the Battle of Malvern Hill.[30]

Disposition of armies

Throughout the Seven Days Battles, Lee's forces had been disjointed and scattered, to varying extents, for one reason or another. These misfortunes continued during the Battle of Malvern Hill, with both Magruder and Huger making mistakes in the deployment of their forces.[20][31]

At first, Magruder's units were behind Stonewall Jackson's column while marching down the Long Bridge Road. Along this road were several adjoining pathways. One led from Glendale to Malvern Hill, called the Willis Church Road by some locals, and the Quaker Road by others, including Lee's mapmakers. Another of these paths began near a local farm and led southwesterly to the River Road—some locals called this the Quaker Road, including Magruder's guides. During his march to Malvern Hill, Magruder told his guides to lead his army down the Quaker Road. Instead of taking Magruder's forces down the Quaker Road which was shown on Lee's map, the guides led his army down the Quaker Road they knew. James Longstreet watched in awe as Magruder's procession marched away from the battle field. He eventually rode after Magruder, and persuaded him to reverse course. They reached the battlefield eventually, after wasting three hours marching.[31]

One of Magruder's men, Major Joseph L. Brent, rode ahead of the column on the Long Bridge Road, eventually reaching the day's battlefield. When he arrived, Brent climbed a tree in a knoll facing Malvern Hill to gain a better vantage point; what he saw was a number of soldiers along the hill's crest clad in blue—McClellan's army was on the hill in force. The Army of the Potomac's disposition in the lead up to the battle was more orderly than Lee's Army of Northern Virginia; like Lee's army, all of McClellan's forces would be concentrated in one place, save for several divisions from Major General Erasmus Keyes's outfit and Keyes himself, who were posted across the James River at Haxall's Landing.[9] "The Union soldiers were resting in position," Brent recalled, "some sitting or lying down, and others moving at ease or disappearing behind the ridge."[32] He also saw the muzzles of cannons that rimmed the hill's slope. Brent thought the Union line "seemed almost impregnable".[32]

Brigadier General Huger and his men had also found themselves in a delicate predicament. Huger was worried about clashing with Union forces while marching towards Malvern Hill. He deployed two of his brigades, commanded by Brigadier Generals Lewis Armistead and Ambrose Wright, to perform a flanking maneuver around any Federals they found, and alleviate the passageway to Malvern Hill from the Union threat. Longstreet eventually notified Huger that he would be unobstructed by Federal forces if he marched to Malvern Hill. Huger still stayed in place until someone from Lee's headquarters "conducted [them] to the front".[20]

Magruder's and Huger's troubles weighed on Lee's planned setup for his forces. As noon drew near and with no sight of Huger or Magruder, Lee replaced these two forces, who were supposed to be manning the Confederate right flank, with the smaller units of Brigadier Generals Armistead and Wright, Huger's two brigades who had reached the battlefield some time earlier.[33] Despite these mishaps, Malvern Hill would be the first time during the Seven Days Battles that all of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was concentrated in the same place.[20]

Beginning of battle

Not long before the battle began, Lee's force encountered another mishap. On the Confederate left flank, Stonewall Jackson had only ten batteries; the other seven, from D.H. Hill's division, were having their ammunition replenished. Furthermore, Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield, Jackson's capable chief of artillery, was sick. Jackson, once an artillery instructor at the Virginia Military Institute, had to assume Crutchfield's duties.[34]

Nevertheless, it was the Confederates that started the battle when in the early afternoon hours, the Rowan Artillery of Brigadier General William H.C. Whiting's division fired from their position on the Confederate left flank, upon Brigadier General Darius Couch's division of the IV Corps, who were near the center of the Union line. This began a fierce firefight between the Union's eight batteries and thirty seven guns concentrated against three Confederate batteries and sixteen guns. The Union fire silenced the Rowan Artillery and made their position untenable.[lower-alpha 3] The other two Confederate artilleries, placed by Jackson himself, were in somewhat better positions, and managed to keep firing.[37] The firefight awoke three Union boats on the James—the ironclad USS Galena, and the gunboats USS Jacob Bell and USS Aroostook[lower-alpha 4]—lobbing missiles twenty inches (510 millimeters) in length and eight inches (200 millimeters) in diameter from their position on the James River onto the battlefield.[39]

Captain John E. Beam of the Union's 1st New Jersey Artillery was killed as a result of the Confederate fire, along with a few others; several Union batteries (though none that were actually engaged) had to move to avoid the fire; the Confederate barrage near Malvern house was said to be "galling"; and a soldier near the front of the Union line said Confederate salvo "cut [them] up terribly." Lieutenant Charles B. Haydon of the 2nd Michigan Infantry recalled that he was almost buried in sand and stubble when a Confederate shell exploded near him, and that he caught a ball from a shrapnel shell that stopped rolling near him and had to dodge two more. Haydon noted that most Confederate artillery exploded at least one hundred feet (30 meters) in the air, scattering fragments over the battlefield. Although the barrage by Lee's forces did claim a few lives, Union forces were unfazed and continued their fearsome barrage. Indeed, Lieutenant Haydon recalled falling asleep during the artillery fight.[40]

Artillery fire, both Confederate and Union, continued to boom across the hill for at least an hour. However, the Union barrage began to slacken at about 2:30 pm—at least until Brigadier General Lewis Armistead, at about 3:30 pm,[41] noticed Union skirmishers creeping towards his men where the grand battery on the Confederate right flank was, nearly within rifle range of them. Armistead sent three regiments from his command to push back the skirmishers, thus beginning the infantry part of the battle. The skirmishers were repelled quickly, but Armistead's men found themselves in the midst of an intense Union barrage. The Confederates decided to nestle themselves in a ravine along the hill's slant. This position protected them from the fire, but pinned them down. They did not have enough men to advance any further and retreating would put them back into the crossfire.[42]

Magruder arrives

Not long after the advance of Armistead's regiments, John Magruder and his men arrived on the battlefield, albeit quite late—by this time, it was four in the afternoon. Magruder was told to move to Huger's right. He sent Major Joseph L. Brent to find where Huger's right was. Brent found Huger, who said that he had no idea where his brigades were. Huger was noticeably upset that his men had been given orders by someone other than himself—Lee had told Huger's two brigades under Armistead and Ambrose Wright to advance to the right part of the Confederate line. Upon hearing of this, Magruder was "much perplexed". He employed Captain A.G. Dickinson to find Lee and tell him of the "successful" charge of Armistead's men who were halfway up the hill, and request further orders. At the same time, Brigadier General Whiting sent Lee notice that Union forces were retreating—Whiting mistook the movement of Edwin Sumner's troops, who were adjusting their position to avoid the Confederate fire, and the relaxing of Union fire on his side, which was the Union artillery concentrating their firepower to a different front, as a Federal withdrawal.[43] "General Lee expects you to advance rapidly," wrote Dickinson, in an draft to Magruder. "He says it is reported that the enemy is getting off. Press forward your whole line and follow up Armistead's success."[44]

In obedience to Lee's order, Magruder mustered some five thousand men from the brigades of Ambrose Wright, Major General William Mahone and half of the men from Armistead's brigade who were in the open battlefield. Magruder had also sent for Brigadier General Robert Ransom, Jr., under Huger's command, who noted that he had been given strict instructions to ignore any orders not originating from Huger, and apologetically said he could not help Magruder. Despite this, under Magruder's order at about 5:30 pm, Wright's brigade with Armistead's, then Mahone's brigade, went darting out of the woods and towards the Union line in a "desperate charge".[45] The Confederates also renewed their artillery barrages with the guns of Richard Ewell's division.[46] Colonel William Kent, a Union sharpshooter, recalled "a line of grey coats rush out of the woods towards [them]." Kent noted that the Confederates were perfectly aligned initially, but they began to break up into groups "which acted entirely independently of each other, some rushing forward, and others taking cover..."[47]

After Mahone's and Wright's brigades were repelled, D.H Hill's men charged out of the woods towards the Union line. Hill had been discouraged by the failure of the Confederate artillery, which he dismissed as "most farcical",[34] and asked Stonewall Jackson to supplement Chilton's draft. Jackson's response was to obey the original orders: charge with a yell after Armistead's brigade. No yell was heard for hours, and Hill's men began building bivouacs to sleep in. In the middle of this exercise, Hill heard an loud yell from the right flank, where Armistead was supposed to be. "That must be the general advance!" said Hill. "Bring up your brigades as soon as possible and join in it."[48] Hill's five brigades, with some 8,200 men, did not attack the Federal line in unity. Instead came five different charges. Furthermore, Hill's units had to contend with the dense woodlands around the Quaker Road and Western Run, which destroyed any order they may have had. "We crossed one fence, went through another piece of woods, then over another fence [and] into an open field on the other side of which was a long line of Yankees," wrote William Calder of the 2nd Regiment, North Carolina Infantry. "Our men charged gallantly at them. The enemy mowed us down by fifties."[48]

The first attack by Lee's army did barely anything to turn the tide of battle, but this did not deter Magruder, who rode back and forth across the battlefield, launching unit after unit into a charge of the Union line. Robert Ransom's unit, after they finally showed up with Huger's permission, attacked the Union western flank. Ransom's men, guided by the flashing light of the cannons amidst an encroaching darkness, did manage to come the closest to the Union line than any Confederates that day; however, Brigadier General George Sykes's artillery repelled that attack.[49] Two of Magruder's brigades, under Brigadier Generals Joseph B. Kershaw and Paul Jones Semmes, arrived to the front and were quickly sent in after Ransom; they were repulsed not long after.[50] Hill's force, on the other hand, had had enough and left the battlefield.[51] Major General Lafayette McLaws's two brigades made the final charge of the day; like the charges before them, it was to little effect.[52]

When night had fallen, Brigadier General Isaac Trimble began gathering his men for another attack on the Union line. Stonewall Jackson saw Trimble in his preparations and asked him what he was doing. "I'm going to charge those batteries, sir," Trimble replied. Trimble thought he'd seen a chance to take Darius Couch's battery through a flanking maneuver after surveying the Union line with D.H. Hill. "I guess you better not try it," advised Jackson. "General D.H. Hill just tried it with his whole Division and has been repulsed. I guess you better not try it, sir."[53] With the infantry part of the battle over, Union artillery continued to boom across the hill. They stopped firing at 8:30 pm, leaving a wreath of smoke upon the crest's edge, and ending the action on Malvern Hill.[54]

Aftermath

The scene after the battle on Malvern Hill was ghastly. The cries of the wounded "tore through the night air." Brigadier General Porter Alexander recalled that "[the scene] could not fail to move with pity the heart of friend or foe."[55] Another Union soldier heard "groans from some, prayers from others, curses from this one, and the uncomplaining silence of the hero."[55] The sunlight on July 2, the day after the battle, shone over a grisly scene of mangled dead from both sides of the conflict. When speaking to Private Moxley Sorrel, Major General Richard S. Ewell questioned, "Can you tell me why we had five hundred men killed dead on this field yesterday?"[56] Confederate Colonel John W. Hinsdale noted that the trees around Malvern Hill were destroyed by grapeshot and shells, and saw a battery position laden with dead horses. Another Confederate of the Maryland Line, named Washington Hands, recalled that many of the bodies were "horribly mangled" by the artillery, and suffered the even greater indignity of having tree limbs, weakened by artillery, fall on top of their resting places.[57] Colonel William W. Averell, a Union cavalryman, gave a detailed description of the scene that morning:

By this time, the level rays of the morning sun from our right were just penetrating the fog, and slowly lifting the clinging shreds and yellow masses. Our ears had been filled with agonizing cries from thousands before the fog was lifted, but now our eyes saw an appalling spectacle upon the slopes down to the woodlands half a mile away. Over five thousand dead and wounded men were on the ground, in every attitude of distress. A third of them were dead or dying, but enough were alive and moving to give to the field a singular crawling effect. The different stages of the ebbing tide are often marked by the lines of flotsam and jetsam left along the sea-shore. So here could be seen three distinct lines of dead and wounded, marking the last front of three Confederate charges of the night before. Groups of men, some mounted, were groping about the field.[58]—Colonel William W. Averell of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry, written some twenty years after the Battle of Malvern Hill.

Following the battle, the horrors of war were shown in stunning clarity. Newspapers around the country were filled with the names of the dead, wounded and missing. Both capitals, Washington and Richmond, became hospitals. Ships sailed from the Peninsula to Washington carrying the wounded. Kin to dead and wounded of the Seven Days tried to locate their loved ones. Richmond, nearest to the battlefields of the Seven Days, was overwhelmed with an immense numbers of casualties. "We lived in one immense hospital, and breathed the vapors of the charnel house," a woman remembered. Graves could not be dug quickly enough and the hospitals and doctors were overwhelmed. People from about the Confederacy descended upon Richmond to care for the conflict's casualties.[59]

Casualties

The Confederates counted some 5,650 casualties. Some 30,000 Confederates engaged that day, though several thousand more endured the Union shelling.[60][61] Brigadier General Whiting's unit suffered 175 casualties in the Malvern Hill conflict, even though they had limited involvement in the assaults. Charles Winder's brigade of just over 1,000 men suffered 104 casualties in their short involvement in the battle. D.H. Hill estimated that more than half of all the Confederate killed and wounded at Malvern Hill were as a result of artillery fire. Additionally, across the entire Seven Days battles, the Confederates suffered some 20,614 casualties; about 22 percent[62] of their total force. Of those casualties, 3,478 were killed, 16,261 were wounded and 875 were missing. Lee's army would not see this many casualties again until the Battle of Gettysburg. The Army of Northern Virginia never regained its size before the Seven Days Battles.[63]

Conversely, out of more than 27,000 Federals engaged, McClellan's Army of the Potomac suffered some 3,000 casualties atop Malvern Hill.[61][64] In the entire Seven Days Battle, some 1,734 soldiers were killed, with 8,062 wounded and 6,053 missing, for a total casualty count of 15,849,[63] some 18 percent of McClellan's total force.[62] Of the missing, about 2,836 were from the conflict at Gaines's Mill, fought four days before Malvern Hill. This number was almost equivalent to the number of missing after Savage's Station, fought two days prior. The remainder of the missing were likely captured along the roads to Harrison's Landing. Lee reported capturing ten thousand Federal soldiers.[63]

Fitz John Porter's V Corps sustained over half the killed in the Seven Days conflicts and almost half of the wounded or missing. Porter's Pennsylvania Reserves accounted for 20 percent of the entire army's losses. George McCall's division lost more than one-third of its strength; George Morell's division lost one-fourth of their men; and both George Sykes's and Henry Slocum's units lost one-fifth of their men. On the Confederate side, four of James Longstreet's six brigades lost 49 percent of their men. On the whole, Longstreet lost 40 percent of his men during the Seven Days. One of D.H. Hill's brigades lost 41 percent of its strength at Malvern Hill alone.[65]

Reasons for outcome

The battle of Malvern Hill was a resounding Union tactical victory. Colonel Henry Hunt, the Union chief artillerist, who accumulated and concentrated the Union guns, did commendable work, as did Colonel A.A. Humphreys, the principal topographical engineer, who placed the troops. The ground on Malvern Hill was used effectively and the Union line had depth with a healthy amount of rested troops on hand to defend it. Fitz John Porter, the de facto commander for the day, played an important role in this. He posted his men well on June 30, and stationed reinforcements near to the Union line. Darius Couch, whose forces comprised half of the Union center, positioned his reinforcements skilfully as well and cooperated with George Morell, whose units formed the other part of the Union middle.[66] In fact, one veteran of the War wrote, "No troops were ever better handled; never was better military skill displayed than by him."[67] The infantrymen performed well also. As Brian K. Burton notes in Extraordinary Circumstances, "[the infantrymen] stayed behind the guns most of the time and did not advance too far during countercharges. This behavior allowed the gunners a clear field of fire." Furthermore, if more of anything was needed—infantry or artillery—it was available.[68][lower-alpha 5] At the forefront of the Union victory was the artillery. Much was said on both sides about the power of the fire that day. Some of the artillery was operated without sponging.[70][lower-alpha 6] One battery launched fourteen hundred rounds and remained in their position the entire day.[70]

A number of shortcomings in planning and execution contributed to the debacle suffered by the Confederates. The Confederate brigade leaders performed, with the exception of Robert Ransom's unwillingness to commit his troops and a few other minor instances; Burton surmises that the blame of July 1 must lie with the overall commanders.[72] James Longstreet's confidence about the artillery strategy might have weighed heavily on Lee's decisions. However, Longstreet's suggestions to Lee were just proposals with no guarantee of success.[72][lower-alpha 7] Some blame might be ascribed to Magruder for the defeat. Magruder was led astray by bad maps and faulty guides, which caused him to reach the battlefield late. As a result of this, Lee's plans were botched—Magruder received Chilton's draft late, and with no time attached to it, there was no way for Magruder to ascertain the recentness of the order,[73][lower-alpha 8] and Magruder's thirty artillery pieces could not be used in either grand battery, as the fire from the Union would have hampered their efforts in moving them.[74] Furthermore, Magruder was riding to and fro across the battlefield, making it hard for him to be found. Despite these mishaps, Burton says Magruder cannot be reasonably blamed for his attacks on the Union line: he was responding to Lee's order to follow up Armistead's "success" and did initially try to form a unified attack on the Union line.[75][lower-alpha 9]

Lee might also share some blame for the Malvern Hill defeat. Though he put rested troops on the field and accepted Longstreet's suggestions, which did not commit him to a charge, Lee was not present on the battlefield to observe the fighting.[77][lower-alpha 10] He might have stopped Whiting's artillery from firing, prevented Armistead's charge, and countermanded Magruder's offensive.[79] Historian Stephen W. Sears points out that Lee's ineffective communication with his generals may have contributed to the defeat.[44] Several other factors may have played into the Confederate repulse, including Major General Theophilus Holmes's refusal to participate in the battle, dismissing fighting as "out of the question".[20][lower-alpha 11]

After battle

McClellan goes to Harrison's Landing

Despite the strength of Malvern Hill, as demonstrated in the battle, McClellan felt he needed to continue with his planned withdrawal to Harrison's Landing, to Fitz John Porter's chagrin. Porter felt that the Army of the Potomac should "reap the full fruits of their labors," and with enough food and ammunition, McClellan's force could remain atop the hill or perhaps even continue their advance to Richmond. Porter could have made a convincing case as well: the Confederates were in ignominious disarray, the spirit of defeat, according to Campbell Brown of Richard Ewell's detachment, hung like an albatross over Lee's men and a fair portion of McClellan's men had not fought at Malvern Hill or any of the conflict the day prior and would be open to an advance. Porter's sentiment was also shared by several in McClellan's camp.[26] He had spent the night trying to convince McClellan to stay on the hill or advance to Richmond, but in lieu of McClellan's "facts"—he insisted Confederate troops greatly outnumbered his own; he felt he could not protect Harrison's Landing from his current position at Malvern Hill; and he feared being cut off from his supply depot—McClellan's mentality prevailed.[26]

The Union batteries were off to Harrison's Landing soon after the end of the Battle of Malvern Hill. At about the same time, McClellan's engineers began moving to Harrison's Landing. George Morell's outfit began marching at about 11 pm. The Pennsylvania Reserves began marching shortly before midnight, as did Darius Couch's division. Unit after unit would follow, and within hours, McClellan's Army of the Potomac, almost in its entirety, was marching towards Harrison's Landing.[82]

Rain was pouring and the roads had turned to mud by the time the Federals began marching. Conditions grew so wearying that a Union soldier described the march as "tedious [and] tiresome."[83] At 10 am on July 2, Colonel William Averell, the last on the hill, withdrew. As they left, they destroyed twelve wagons for which they could not find mules to pull. Once these men had crossed the Turkey Island Bridge, they destroyed the bridge and felled trees over it to stymie any pursuit, leaving the James River between the Union and Confederate armies.[58] The first of McClellan's units had begun to trickle into Harrison's Landing between 2 and 3 am on July 2. McClellan himself had boarded the Galena towards the end of the action on Malvern Hill and stayed aboard until the next day. Upon arrival at Harrison's Landing on July 2, he met a message from President Lincoln: "If you think you are not strong enough to take Richmond just now, I do not ask you to try just now."[84] Lincoln promised reinforcements for McClellan, which he upheld in the form of the five thousand men under Brigadier General Orris S. Ferry he sent. Foodstuffs and other supplies came from the White House, Virginia Union supply base as well.[84] McClellan and his army were at Harrison's Landing until August 16, when they began marching towards Fort Monroe.[85]

Lee returns to Richmond

Ambrose Wright, William Mahone and one regiment from Robert Ransom's outfit remained on the hill after the battle. They did request help however; Wright wrote to Magruder, "for God's sake, relieve us soon and let us collect our brigades."[86] Relief did not come, and they stayed the night on the hill. Lewis Armistead's regiments occupied the hill as well; they stayed the night in the ravine on the hill's slope that they had retreated to during the battle. The areas around Malvern Hill hosted much of the rest of Lee's army. Some of the Confederates were close enough to hear the sounds made by the Army of the Potomac retreating under cover of darkness, and see the lanterns of Northerners helping their wounded. One noted that the "wagons and artillery made a great deal of noise."[86] Others of Lee's outfit, apparently not hearing the Union wagons, feared another attack. Richard S. Ewell, vexed by the thought, had dozens of ammunition wagons moved to White Oak Swamp so they would be safe in the event of a quick withdrawal.[86] Other men woke Stonewall Jackson to discuss the army's current situation. "Please let me sleep," Jackson said. "There will be no enemy there in the morning."[86]

The day after the battle, Lee, with Stonewall Jackson, was at Poindexter farm dictating messages to be mailed out and discussing future plans when he met President Jefferson Davis, who had made the short trek from Richmond to Malvern Hill. Lee, apparently not expecting Davis, introduced him to Stonewall Jackson and the three men began discussing plans for the army's future. They considered immediately pursuing McClellan; however, in view of the rain and confusion, Davis and Lee deemed large-scale pursuit of McClellan's army too risky. Jackson disagreed, saying, "They have not all got away if we go immediately after them."[87] Jackson even had the bodies of the dead moved so that his soldiers had a clear line of attack when pursuing McClellan. However, Davis and Lee thought it necessary to rest the army. They did not completely rule out a pursuit though; Lee even ordered J.E.B. Stuart to reconnoiter McClellan's position for future attacks.[88]

Stonewall Jackson's men positioned themselves near Willis Methodist Church. James Longstreet's and A.P. Hill's outfits camped near the Poindexter farm. Lee kept D.H. Hill's units, along with Benjamin Huger's and John Magruder's, near Malvern Hill, as he had heard reports that McClellan might move south of the James River, take Drewry's Bluff and march on Richmond from there; he kept their outfits on Malvern Hill to block McClellan if these reports were true. Lee also ordered Theophilus Holmes to move to Drewry's Bluff. Meanwhile, D.H. Hill spent days removing the wounded, burying the dead and cleaning up the battlefield, with help from Magruder and Huger's units.[89]

The Drewery's Bluff threat was assuaged in Lee's mind when J.E.B. Stuart reported that McClellan was in Harrison's Landing. Lee had decided to keep the men on Malvern Hill through July 3 because of this threat. However, on July 4, 1862, the eighty-sixth anniversary of American Independence, Lee's men were marching towards Harrison's Landing.[90] At the head of the column, Richard S. Ewell's men began engaging Federals with skirmish fire. The Union soldiers were atop Evelington Heights, a sixty feet (18 meters) elevation approximately thirteen miles (21 kilometers) over Harrison's Landing. A strong Union line, fortified by artillery and warships on the James, was visible on the heights. Some of Lee's men still wanted to attack, but Lee decided to observe. He made his headquarters a few miles north of the heights. Lee and his men stayed nearby the heights for several days, in case a weakness in the Union line became available for attack. No weakness presented itself though, and on July 7, Lee ordered Robert Ransom and his outfit to join Theophilus Holmes at Drewry's Bluff, and Huger and his men to move to the south of the James. The next day, Lee ordered Jackson, Longstreet and D.H. Hill back to Richmond. By the end of July 8, the entire Army of Northern Virginia, save for cavalry stations and picket forces, was back near Richmond. Lee himself was already thinking of the next campaign; the campaign on the Virginian Peninsula was over.[91]

Reactions and effects

Despite the defeat on Malvern Hill, Lee had accomplished the original goal of his Seven Days offensive: the deliverance of Richmond. Newspapers in Richmond made no small fuss of it after the battle. "No captain that ever lived could have planned or executed a better plan," said the Dispatch. Another newspaper, the Whig, hailed Lee's victory as well, saying Lee "has amazed and confounded his detractors by the brilliancy of his genius, the fertility of his resources, his energy and daring." The Enquirer remarked that the victory was "achieved in so short a time with so small cost to the victors. I do not believe the records of modern warfare can produce a parallel."[92] The comment of "so small cost to the victors" may be worthy of debate but the government in Richmond was not one to correct the record. Confederate Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory proclaimed, "the Great McClelland [sic] the young Napoleon now like a whipped cur lies on the banks of the James River crouched under his Gun Boats." Indeed, throughout Richmond and the once-beleaguered South, there was an exultant mood.[93]

Lee was not exultant, but "deeply, bitterly disappointed" at the result. "Our success has not been as great or complete as we should have desired," Lee wrote to his wife. In a report, he wrote, "Under ordinary circumstances, the Federal Army should have been destroyed."[94] D.H. Hill shared Lee's bitterness. Hill wrote to his wife that his men were "most horribly cut up." The "blood of North Carolina poured like water," Hill, himself a North Carolinian, wrote of the Battle of Malvern Hill. In a post-war article, a part of the publication Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, he wrote, "[the Battle of Malvern Hill] was not war; it was murder."[95] Lee did not distribute blame for the failure to reach his desired result, but there were repercussions. Several commanders, including Theophilus Holmes and John Magruder were reassigned,[96] and his army was reorganized into two wings, one under Stonewall Jackson and another under James Longstreet.[93] Further, Confederate artillery would now be moved in battalion-sized units, at the head of Confederate columns.[97]

The dialogue box reads: "Fight on my brave Soldiers and push the enemy to the wall, from this spanker boom your beloved General looks down upon you."

In McClellan's case, his success on Malvern Hill was overshadowed by his overall defeat in the Seven Days Battles; McClellan blamed the "heartless villains" in Washington who, in his mind, authored his defeat. They sought to "sacrifice as noble an Army as ever marched to battle." McClellan singled out Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and his associates for the blame of his defeat. His enmity against Stanton was deep and substantial.[98] "They are aware that I have seen through their villainous schemes," writes McClellan to his wife, "& that if I succeed my foot will be on their necks."[98] McClellan was comforted by his opinion that the events on the Peninsula were God's will. "I think I begin to see [God's] wise purpose in all of this," he wrote to his wife. "If I had succeeded in taking Richmond now, the fanatics of the north might have been too powerful & reunion impossible."[98]

Some of McClellan's soldiers voiced their continued confidence in him, saying, "Under the circumstances, I think [McClellan] has accomplished a great feat." Another soldier wrote, "We have full confidence in McClellan yet; but wish [the] war department rest in Purgatory for not reinforcing him."[99] The "full confidence" comment was not unanimous though, with a soldier of the Excelsior Brigade writing, "McClellan was whipped" and "I do not think McClellan has come up to the mark." Another soldier from Pennsylvania wrote, "He pretends that it was his intention to do just as he did but I believe he utters a falsehood when he says so; the boys do not have as much confidence as they used to,"[99] and one of McClellan's engineers, Lieutenant William Folwell, wondered why "they deify a General whose greatest feat has been a masterly retreat."[98]

The American public met McClellan's defeat with despondency, and his reputation was tarnished. Some liberals and conservatives abandoned the Democratic McClellan. His being on the Galena during the Battle of Malvern Hill generated scorn from newspapers and tabloids around the country, especially when he ran for president in 1864. He was labelled either an imbecile or a traitor.[100] President Lincoln was also losing faith in McClellan.[101] On June 26, the day of Lee's first offensive during the Seven Days, the Army of Virginia was formed and the command given to Major General John Pope. While McClellan was at Harrison's Landing, parts of his Army of the Potomac were continuously being reassigned to Pope. Pope and his Army of Virginia left for Gordonsville, Virginia on July 14, setting the stage for the subsequent Second Battle of Bull Run.[102]

In popular culture

In his Battle-Pieces publication, Herman Melville penned a poem about the battle, titled with the same name as the hill on which it was fought. In the poem, Melville questions the elms of Malvern Hill of whether they recall "the haggard beards of blood" the day of the battle.[103]

Battlefield preservation

The battlefield at Malvern Hill is credited by the National Park Service as being "the best preserved Civil War battlefield in central or southern Virginia." Most recent preservation efforts there have been the consequence of cooperative efforts between Richmond National Battlefield Park and the Civil War Trust.[104] The Trust has purchased 953 acres at the heart of the battlefield since 2000. Its efforts have been bolstered by the Virginia Land Conservation Fund, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, and officials from Henrico County. Most of this tract wraps around the intersection of Willis Church Road and Carter's Mill Road. The land includes the Willis Church Parsonage, which served as the starting point of the Confederate assaults on the day of the battle and the ruins of which remain visible today.[105] Recent preservation efforts include the acquisition of the Crew house in 2013.[106] Some 1,332.6 acres of land is protected on and around Malvern Hill to preserve the battlefield, according to the National Park Service. Driving and walking tours, among other services, are also offered at the site.[107]

See also

- Richmond in the Civil War

- Virginia in the American Civil War

- List of American Civil War battles

- List of Virginia Civil War units

Notes

Additional notes

- ↑ It is debatable whether he actually believed this or was inflating Confederate numbers to better his case.[6] In McClellan's telegrams to Washington, he estimated the Confederate army at 200,000. However, with P.G.T. Beauregard and his division in Mississippi, Lee actually had less than one hundred thousand men.[7]

- ↑ Chilton's draft effectively left the attack solely at the discretion of Lewis Armistead, who had never before held command of a brigade during battle.[25]

- ↑ The many accounts of incidents caused by the Union artillery on Malvern Hill led the artillery barrage to be called one of the greatest during the Civil War. For example, Brigadier General Jubal Early, Colonel James Walker of the 13th Virginia Infantry and Willy Fields, Walker's aide-de-camp, were eating nearby the battlefield when a shell landed near Fields and exploded with enough force to push Fields into the air. The subsequent fall caused a mortal concussion. Further, an artilleryman from William H.C. Whiting's batteries had his head torn almost completely from his body after a projectile passed through a tree he was sitting under.[35] Another of Whiting's men, wounded by artillery that exploded almost in his face, wrote to his home that "the same shell that wounded me wounded four others in my company and killed my bosom friend T.J. Bennett of Marietta [Georgia]."[36] Several Union shells landed near to Stonewall Jackson as he was riding with Whiting and Richard S. Ewell into the Poindexter farm. When a shell hit a nearby horse, Jackson's horse was frightened and ran, pulling Jackson to the ground. The horse kept going for some twenty to thirty yards (18 to 27 meters), until Jackson stopped it. Seconds later, the same shell exploded some twenty feet (6.1 meters) from Jackson.[35]

- ↑ Sources do not make clear what time the warships began their barrage. However, the Galena returned from Harrison's Landing with McClellan on-board at about 3:30 pm, and it is unlikely that it participated in the salvo prior to that time.[38]

- ↑ At Gaines's Mill, nearly all men fought that day. At Malvern Hill, the III Corps, with some 10,000 men, was entirely unused. Moreover, about 10,000 men from the II Corps were close at hand to support the Union line if needed, and some thirty-eight guns were still in reserve by the end of the day, having not fired a single round of ammunition.[69]

- ↑ Operating a gun without sponging is incredibly dangerous. Sponging would have prevented any spark or fire in the gun from causing it to burst or explode. If a gun explodes, it might cause immense harm to the crew operating it.[71]

- ↑ Stonewall Jackson also had problems gathering the artillery for the assault. The Confederate practice of moving artillery with individual units instead of in one mass and the terrain of Malvern Hill itself contributed to this issue. A potential solution to this problem lay with Brigadier General William N. Pendleton's fourteen batteries. However, Pendleton was never contacted by Lee's headquarters, and spent July 1 "await[ing] events and orders, in readiness for whatever service might be called for." These orders never came, and Pendleton's batteries went unused.[34]

- ↑ In fact, when Magruder sent Lee word of Lewis Armistead's advance up the hill, he still had not received the order.[74]

- ↑ Lee took Magruder to task about this charge though.[74] On the evening of the battle, Lee rode through the camps; seeing John Magruder, he confronted him. "General Magruder," Lee began, "why did you attack?" Magruder responded, "In obedience to your orders, twice repeated."[76] In To the Gates of Richmond, Historian Stephen W. Sears explains that this exchange could only mean that Lee intended for both Captain Dickinson, who delivered the order to Magruder, and Magruder himself, to soften the order at their discretion. Sears adds that this incident is another testament to the necessity for Lee to write his own communications to his lieutenants, instead of leaving his orders open to interpretation.[44]

- ↑ A potential explanation for this lies with Lee's reported fatigue and disappointment over the past battles of the Seven Days.[78]

- ↑ Theophilus Holmes and his men had clashed with Porter and his men the day before Malvern Hill after Holmes heard word of Union soldiers atop the hill. With these reports, and with Lee's approval of his plans, Holmes marched to Malvern. The ensuing engagement "frightened [Holmes's men] terribly."[80] The Confederates opened fire at about 4 or 5 pm, and the Union artillery was quick to respond. Shell fragments and broken tree trunks and branches showered the Confederates when the Union's thirty-six guns joined the fight. Moreover, nine-inch and eleven-inch (230 millimeter and 280 millimeter) Dahlgren guns and one hundred-pounder (45 kilogram) Parrott rifles aboard the Union ships Aroostook and Galena, now awakened by the artillery fire, rained their ammunition down upon the Confederates.[80] Amidst the chaos, Holmes stepped out of the Malvern house, which he had taken as his headquarters, and observed, "I though I heard firing." Fitz John Porter, on the other hand, slept right through the entire skirmish. By the time the engagement was done, three of Holmes's men were dead and fifty wounded.[81]

Citations

- ↑ Sears 1992, pp. 21–24

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 24

- ↑ Eicher 2002, p. 275

- ↑ Salmon 2001, p. 63

- ↑ Salmon 2001, p. 63; Eicher 2002, p. 275

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Salmon 2001, pp. 63–64

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 55–56; Salmon 2001, pp. 64–66

- ↑ Salmon 2001, pp. 64–66

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Sears 1992, p. 310

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Kennedy 1998, p. 101

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Eicher 2002, p. 293

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 309

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sears 1992, p. 311

- ↑ Sears 1992, pp. 311 & 315

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Sears 1992, pp. 311–312

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 312

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Sears 1992, p. 309

- ↑ Sears 1992, pp. 299 & 312; Burton 2010, pp. 295–296

- ↑ Sears 1992, pp. 312–313

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Sears 1992, p. 313

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 314

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Burton 2010, pp. 309–310

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Kennedy 1998, pp. 101–103

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Sears 1992, pp. 314–317

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Sears 1992, p. 317

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Burton 2010, pp. 366–368

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 367

- ↑ Snell 2002, p. 126

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 309; Salmon 2001, p. 119

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 314

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Sears 1992, pp. 314–315

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Sears 1992, p. 316

- ↑ Salmon 2001, p. 122; Sears 1992, p. 316

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Sears 1992, p. 318

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Burton 2010, p. 317

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 320

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 316–317; Dougherty 2010, p. 136; Abbott 2012, p. 107

- ↑ Sweetman 2002, p. 66

- ↑ Abbott 2012, p. 108; Sears 1992, p. 330; Burton 2010, p. 317; Sweetman 2002, p. 66

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 318

- ↑ Hattaway 1997, p. 89

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 322

- ↑ Sears 1992, pp. 322–324; Burton 2010, pp. 327–330

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Sears 1992, p. 323

- ↑ Sears 1992, pp. 324–325

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 331

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 325

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Sears 1992, pp. 325–326

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 334; Burton 2010, pp. 348 & 350

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 350

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 340; Sears 1992, p. 332

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 334

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 335

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 334; Burton 2010, p. 356; Dougherty 2010, p. 137

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Burton 2010, pp. 370–371

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 375

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 376

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Burton 2010, p. 374

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 387–388

- ↑ Kennedy 1998, p. 137

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Burton 2010, p. 357

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Kennedy 1998, p. 139

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Burton 2010, p. 386

- ↑ Dougherty 2010, p. 137

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 387

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 358–361

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 360

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 359–360

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 358–359

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Burton 2010, pp. 358–360

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 359

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Burton 2010, p. 361

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 364

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 Burton 2010, p. 362

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 362

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 358

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 362–363

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 363

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 363–364

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Sears 1992, p. 292

- ↑ Sears 1992, pp. 291–292

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 368–369

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 371

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Burton 2010, p. 379

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 355

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 86.3 Burton 2010, p. 370

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 377

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 375–377; Salmon 2001, p. 124

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 377–378

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 384

- ↑ Burton 2010, pp. 384–385; Dougherty 2010, p. 139

- ↑ Sears 1992, pp. 342–343

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Sears 2003, pp. 55–56

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 391

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 340

- ↑ Sears 1992, p. 343

- ↑ Hattaway 1997, p. 93

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 98.3 Sears 1992, p. 347

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Burton 2010, pp. 388–389

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 389

- ↑ Burton 2010, p. 398

- ↑ Hattaway 1997, pp. 91–95

- ↑ Rollyson, Paddock & Gentry 2007, pp. 115–116

- ↑ "The Battle of Malvern Hill". National Park Service. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Malvern Hill Battlefield Facts.". CivilWar.org. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ↑ "The Crew House video". Civil War Trust. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Virginia Battlefield Profiles" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

Sources

- Abbott, John Stevens Cabot (2012). The history of the Civil War in America: comprising a full and impartial account of the origin and progress of the rebellion, of the various naval and military engagements, of the heroic deeds performed by armies and individuals, and of touching scenes in the field, the camp, the hospital, and the cabin. Charleston, SC: Gale, Sabin Americana. ISBN 1275836461.

- Burton, Brian K. (2010). Extraordinary Circumstances: The Seven Days Battles. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253108446.

- Dougherty, Kevin (2010). The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: A Military Analysis. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1604730617.

- Eicher, David J. (2002). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. London: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0743218469.

- Hattaway, Herman (1997). Shades of Blue and Gray: An Introductory Military History of the Civil War. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826211070.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (illustrated, revised ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0395740126.

- Rollyson, Carl E.; Paddock, Lisa O.; Gentry, April (2007). Critical Companion to Herman Melville: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York, NY: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438108478.

- Salmon, John S. (2001). The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide (illustrated ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0811728684.

- Sears, Stephen W. (1992). To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign. New York, NY: Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0899197906.

- Sears, Stephen W. (2003). Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (reprint ed.). New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0618344195.

- Snell, Mark A. (2002). From First to Last: The Life of Major General William B. Franklin (illustrated ed.). New York, NY: Fordham University Press. ISBN 0823221490.

- Sweetman, Jack (2002). American Naval History: An Illustrated Chronology of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, 1775–present (illustrated ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1557508674.

Further reading

- Abbot, Henry L. (2010). Siege Artillery in the Campaigns Against Richmond: With Notes on the Fifteen-Inch Gun. Ann Arbor, MI: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1164867709.

- Brasher, Glenn D. (2012). The Peninsula Campaign & the Necessity of Emancipation. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807835447.

- Department of Military Art and Engineering (1959). "West Point Atlas of American Wars". New York, NY: Frederick A. Praeger. OCLC 5890637.

- Gabriel, Michael P. "Battle of Malvern Hill". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

- Gallagher, Gary W. (2008). The Richmond Campaign of 1862: The Peninsula & the Seven Days. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807859192.

- Savas, Theodore P.; Miller, William J. (1995). The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: Yorktown to the Seven Days, volume 1. Campbell, CA: Woodbury Publishers. ISBN 1882810759.

- Savas, Theodore P.; Miller, William J. (1996). The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: Yorktown to the Seven Days, volume 2. Campbell, CA: Woodbury Publishers. ISBN 1882810767.

- Savas, Theodore P.; Miller, William J. (1997). The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: Yorktown to the Seven Days, volume 3. Campbell, CA: Woodbury Publishers. ISBN 1882810147.

- Wheeler, Richard (2008). Sword Over Richmond: An Eyewitness History of McClellan's Peninsula Campaign. Scranton, PA: Random House Value Publishing. ISBN 0785817107.

External links

- Malvern Hill battlefield page: battle maps, photos, history articles, and battlefield news. (Civil War Trust)

- Animated history of the Peninsula Campaign.

- Malvern Hill by Herman Melville; hosted by the Poetry Foundation.