Battle of Kalavrye

| Battle of Kalavrye | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Miniature of Alexios Komnenos, the victor of Kalavrye, as emperor | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Imperial forces of Nikephoros III Botaneiates | Rebel forces of Nikephoros Bryennios the Elder | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Alexios Komnenos | Nikephoros Bryennios (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

5,500–6,500 (Haldon)[1] 8,000–10,000 (Birkenmeier)[2] | 12,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy | Heavy | ||||||

The Battle of Kalavrye (also Kalavryai or Kalavryta) was fought in 1078 between the Byzantine imperial forces of general (and future emperor) Alexios Komnenos and the rebellious governor of Dyrrhachium, Nikephoros Bryennios the Elder. Bryennios had rebelled against Michael VII Doukas (r. 1071–1078) and had won over the allegiance of the Byzantine army's regular regiments in the Balkans. Even after Doukas's overthrow by Nikephoros III Botaneiates (r. 1078–1081), Bryennios continued his revolt, and threatened Constantinople. After failed negotiations, Botaneiates sent the young general Alexios Komnenos with whatever forces he could gather to confront him.

The two armies clashed at Kalavrye on the Halmyros river. Alexios Komnenos, whose army was considerably smaller and far less experienced, tried to ambush Bryennios's army. The ambush failed, and the wings of his own army were driven back by the rebels. Alexios himself barely managed to break through with his personal retinue, but succeeded in regrouping his scattered men. At the same time, Bryennios's army fell into disorder after having seemingly won the battle, and due to the attack on its camp by its own Pecheneg allies. Reinforced by Turkish mercenaries, Alexios lured the troops of Bryennios into another ambush through a feigned retreat. The rebel army broke, and Bryennios himself was captured.

The battle is known through two detailed accounts, Anna Komnene's Alexiad, and her husband Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger's Material for History, on which Anna's own account relies to a large degree. It is one of the few Byzantine battles described in detail, and hence a valuable source for studying the tactics of the Byzantine army of the late 11th century.[4]

Background

After the defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 against the Seljuk Turks and the deposition of Romanos IV Diogenes (r. 1068–1071), the Byzantine Empire experienced a decade of near-continuous internal turmoil and rebellions. The constant warfare depleted the Empire's armies, devastated Asia Minor and left it defenceless to the increasing encroachment of the Turks. In the Balkans, invasions by the Pechenegs and the Cumans devastated Bulgaria, and the Serbian princes renounced their allegiance to the Empire.[5]

The government of Michael VII Doukas (r. 1071–1078) failed to deal with the situation effectively, and rapidly lost support among the military aristocracy. In late 1077, two of the Empire's leading generals, Nikephoros Bryennios the Elder, the doux of Dyrrhachium in the western Balkans, and Nikephoros Botaneiates, the strategos of the Anatolic Theme in central Asia Minor, were proclaimed emperors by their troops. Bryennios set out from Dyrrhachium towards the imperial capital Constantinople, winning widespread support along his way and the loyalty of most of the Empire's Balkan field army. Bryennios nevertheless preferred to negotiate at first, but Michael VII rebuffed his offers, and Bryennios sent his brother John to lay siege to Constantinople. Unable to overcome its fortifications, however, the rebel forces soon retired. This failure led the capital's nobility to turn to Botaneiates instead: in March 1078 Michael VII was forced to abdicate and retire as a monk, and Nikephoros Botaneiates was accepted into the city as emperor.[6]

At first, Botaneiates lacked any substantial number of troops to oppose Bryennios, who in the meantime had consolidated his control over his native Thrace, effectively isolating the capital from the remaining imperial territory in the Balkans. At first, Botaneiates sent an embassy under the proedros Constantine Choirosphaktes, a veteran diplomat, to conduct negotiations with Bryennios. At the same time he appointed the young Alexios Komnenos as his Domestic of the Schools (commander-in-chief), and sought aid from the Seljuk Sultan Suleyman, who sent 2,000 warriors and promised even more.[7] In his message to Bryennios, the aged Botaneiates (he was 76 years old at his accession) offered him the rank of Caesar and his nomination as heir to the throne. Bryennios agreed in principle, but added a few conditions of his own, and sent the ambassadors back to Constantinople for confirmation. Botaneiates, who likely had initiated negotiations only to gain time, rejected Bryennios's conditions, and ordered Alexios Komnenos to campaign against the rebel.[8]

Prelude

Bryennios had camped at the plain of Kedoktos (a name deriving from the Latin aquaeductus) on the road to Constantinople. His army comprised 12,000 mostly seasoned men from the regiments (tagmata) of Thessaly, Macedonia and Thrace, as well as Frankish mercenaries and the elite tagma of the Hetaireia. Alexios's forces included 2,000 Turkish horse-archers, 2,000 Chomatenoi from Asia Minor, a few hundred Frankish knights from Italy, and the newly raised regiment of the Immortals, which had been created by Michael VII's chief minister Nikephoritzes and intended to form the nucleus of a new army. Estimates of Alexios's total force vary from 5,500–6,500 (Haldon) to some 8,000–10,000 (Birkenmeier), but it is clear that he was at a considerable disadvantage against Bryennios; not only was his force considerably smaller, but also far less experienced than Bryennios's veterans.[9]

Alexios's forces set forth from Constantinople and camped on the shore of the river Halmyros (west of Herakleia, modern Marmara Ereğlisi), near the fort of Kalavrye (Greek: Καλαβρύη). Curiously, and in contravention of established practice, he did not fortify his camp, perhaps so as not to fatigue or dishearten his men with an implicit admission of weakness.[10] He then sent his Turkish allies to scout out Bryennios's disposition, strength and intentions. Alexios's spies easily accomplished their tasks, but on the eve of the battle some were captured and Bryennios too was informed of Alexios's strength.[11]

Battle

Initial dispositions and plans

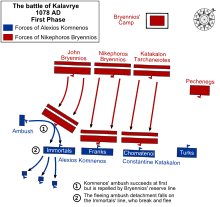

Bryennios arranged his army in the typical three divisions, each in two lines, as prescribed by the Byzantine military manuals. The right wing, under his brother John, was 5,000 strong and comprised his Frankish mercenaries, Thessalian cavalry, the Hetaireia, and the Maniakatai regiment (descendants of the veterans of George Maniakes's campaign in Sicily and Italy). His left wing, 3,000 men from Thrace and Macedonia, was placed under Katakalon Tarchaneiotes, and the centre, under Bryennios himself, comprised 3,000–4,000 men from Thessaly, Thrace and Macedonia. Again, according to standard doctrine, on his far left, about half a kilometer ("two stadia") from the main force, he had stationed an outflanking detachment (hyperkerastai) of Pechenegs.[12]

Alexios deployed his smaller army in waiting near Bryennios's camp, and divided it in two commands. The left, which confronted Bryennios's strongest division, was commanded by himself and contained the Frankish knights to the right and the Immortals to the Franks' left. The right command was under Constantine Katakalon, and comprised the Chomatenoi and the Turks. The latter, according to the Alexiad, were given the role of flank guard (plagiophylakes) and tasked with observing and countering the Pechenegs. Conversely, on the extreme left Alexios formed his own flanking detachment (apparently drawn from among the Immortals), concealed from enemy view inside a hollow. Given his inferiority, Alexios was forced to remain on the defensive. His only chance at success was that his out-flankers, concealed by the broken terrain, would surprise and create enough confusion among Bryennios's men for him and his strong left wing to break through their lines.[13]

Alexios's army collapses

As the rebel forces advanced towards his enemy's line, Alexios's flankers sprung their ambush. Their attack did indeed cause some initial confusion, but Bryennios (or, according to the Alexiad, his brother John, who commanded the right wing) rallied his men and led forth the second line. This counter-attack broke Alexios's flankers; as they retreated in panic, they fell upon the Immortals, who also panicked and fled, abandoning their posts. Although they suffered some casualties from Bryennios's pursuing men, most managed to escape well to the rear of Alexios's army.[14]

Alexios, who was fighting with his retinue alongside the Franks, did not immediately realize that his left wing had collapsed. In the meantime, on his right wing, the Chomatenoi, engaged with Tarchaneiotes's men, were outflanked and attacked in the rear by the Pechenegs, who had somehow evaded Alexios's Turkish flank-guards. The Chomatenoi too broke and fled, and Alexios's fate seemed sealed. At this point, however, the Pechenegs failed to follow up their success, and instead turned back and began looting Bryennios's own camp. After gathering what plunder they could, they left the battle and made for their homes.[15]

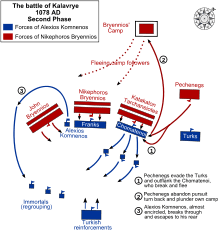

Nevertheless, Bryennios's victory seemed certain, for his wings began to envelop Alexios's Franks in the centre. It was then that Alexios realized his position. Despairing in the face of defeat (and, as Bryennios the Younger records, because he had disobeyed imperial orders to wait for more Turkish reinforcements and feared punishment from Botaneiates), he at first resolved to attempt an all-or-nothing attack on Bryennios himself and decapitate the enemy army, but was dissuaded by his servant. With only six of his men around him, he then managed to break through the surrounding enemy soldiers and to their rear. Confusion reigned there, as a result of the Pecheneg attack on the rebel camp, and in this tumult Alexios saw Bryennios's imperial parade horse, with his two swords of state, being driven away to safety. Alexios and his men charged the escort, seized the horse, and rode away with it from the battlefield.[16]

Having reached a hill behind his army's original position, Alexios began to regroup his army from the units that had broken. He sent out messengers to rally his scattered men with news that Bryennios had been killed, and with his parade horse as evidence. At the same time, the promised Turkish reinforcements began arriving at the scene, lifting his men's morale. All the while, in the battlefield itself, Bryennios's army had closed around Alexios's Franks, who dismounted and offered to surrender. In the process, however, the rebel army had become totally disordered, with units mixed and their formations disordered. Bryennios's reserves had been thrown in confusion by the Pecheneg attack, while his front lines relaxed, thinking that the battle was over.[17]

Alexios's counter-attack

Having restored his surviving forces to order, and aware of the confusion in Bryennios's forces, Alexios decided to counter-attack. The plan he laid out made far greater use of the particular skills of his Turkish horse-archers. He divided his force into three commands, of which two were left behind in ambush. The other, formed from the Immortals and the Chomatenoi under Alexios's own command, was not arrayed in one continuous line, but broken up in small groups, intermingled with other groups of Turkish horse-archers. This command would advance on the rebels, attack them, then feign retreat and draw them into the ambush.[18]

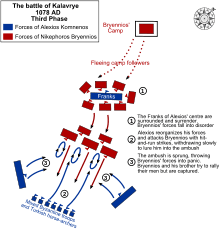

The attack of Alexios's division initially caught Bryennios's men off guard, but, being veteran troops, they soon recovered and once again began to push it back. Retreating, Alexios's troops, and especially the Turks, employed skirmishing tactics, attacking the enemy line and then withdrawing swiftly, thus keeping their opponents at bay and weakening the coherence of their line. Some among Alexios's men chose to attack Bryennios himself, and the rebel general had to defend against several attacks himself.[19]

When the battle reached the place of the ambush, Alexios's wings, likened in the Alexiad to a "swarm of wasps", attacked the rebel army on the flanks firing arrows and shouting loudly, spreading panic and confusion among Bryennios's men. Despite the attempts of Bryennios and his brother John to rally them, their army broke and fled, and other units, which were following behind, did likewise. The two brothers tried to put up a rear-guard defence, but they were overcome and captured.[19]

Aftermath

The battle marked the end of Bryennios's revolt, although Nikephoros Basilakes gathered up much of Bryennios's defeated army and attempted to claim the throne for himself. He too was defeated by Alexios Komnenos, who then proceeded to expel the Pechenegs from Thrace.[20] The elder Bryennios was blinded on Botaneiates's orders, but the emperor later took pity on him and restored him his titles and his fortune. After Alexios Komnenos seized the throne himself in 1081, Bryennios was further honoured with high dignities. He even held command during Alexios's campaigns against the Pechenegs, and defended Adrianople from a rebel attack in 1095.[21] His son or grandson, Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger, was married to Alexios's daughter Anna Komnene. He became a prominent general of Alexios's reign, eventually raised to the rank of Caesar, and a historian.[22]

References

Citations

- ↑ Haldon 2001, p. 128.

- ↑ Birkenmeier 2002, p. 58.

- ↑ Haldon 2001, p. 128; Tobias 1979, p. 201.

- ↑ Tobias 1979, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Birkenmeier 2002, pp. 27–29, 56; Treadgold 1997, pp. 603–607.

- ↑ Birkenmeier 2002, p. 56; Tobias 1979, pp. 194–195; Treadgold 1997, p. 607.

- ↑ Tobias 1979, pp. 195–197; Treadgold 1997, p. 607.

- ↑ Tobias 1979, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Birkenmeier 2002, p. 58; Haldon 2001, pp. 128–129; Tobias 1979, pp. 198, 200.

- ↑ Haldon 2001, p. 128; Tobias 1979, p. 199.

- ↑ Haldon 2001, p. 128; Tobias 1979, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Birkenmeier 2002, pp. 57–58; Haldon 2001, pp. 128–129; Tobias 1979, pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Birkenmeier 2002, pp. 58–59; Haldon 2001, p. 129; Tobias 1979, pp. 200–202.

- ↑ Birkenmeier 2002, p. 59; Haldon 2001, p. 129; Tobias 1979, pp. 202–204, 208.

- ↑ Haldon 2001, p. 129; Tobias 1979, p. 204.

- ↑ Haldon 2001, pp. 129–130; Tobias 1979, p. 206.

- ↑ Haldon 2001, p. 130; Tobias 1979, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Haldon 2001, p. 130; Tobias 1979, p. 209.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Haldon 2001, p. 130; Tobias 1979, pp. 209–211.

- ↑ Birkenmeier 2002, p. 56; Treadgold 1997, p. 610.

- ↑ Kazhdan 1991, p. 331; Skoulatos 1980, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Kazhdan 1991, p. 331; Skoulatos 1980, pp. 224–232.

Sources

- Birkenmeier, John W. (2002). The Development of the Komnenian Army: 1081–1180. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-11710-5.

- Haldon, John (2001). The Byzantine Wars. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1795-0.

- Kazhdan, Alexander Petrovich, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York, New York and Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Skoulatos, Basile (1980). Les personnages byzantins de I'Alexiade: Analyse prosopographique et synthese (in French). Louvain, Belgium: Nauwelaerts. OCLC 8468871.

- Tobias, N. (1979). "The Tactics and Strategy of Alexius Comnenus at Calavrytae, 1078" (PDF). Byzantine Studies/Etudes byzantines 6: 193–211. ISSN 0095-4608.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.