Battle of Fort Sanders

| Battle of Fort Sanders | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Assault on Fort Sanders, by Kurz and Allison, 1891. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ambrose Burnside | James Longstreet | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Ohio | Confederate Forces in East Tennessee[1] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 440 | ~3,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

13 total 8 killed 5 wounded [2] |

813 total 129 killed 458 wounded 226 captured[3] | ||||||

The Battle of Fort Sanders was the decisive engagement of the Knoxville Campaign of the American Civil War, fought in Knoxville, Tennessee, on November 29, 1863. Assaults by Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet failed to break through the defensive lines of Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, resulting in lopsided casualties, and the Siege of Knoxville entered its final days.

Background

The Confederacy had never had effective control of large areas of East Tennessee. There had been little slavery practiced in East Tennessee, because of moral opposition to the practice and the fact that little of the land was suitable to plantation agriculture; pro-Union and Republican sentiment ran high and most East Tennesseans had not been in favor of secession. Therefore, Union forces had little trouble from the local populace when Burnside occupied Knoxville in September 1863; the Army had considerably more difficulty reaching Knoxville over the rugged mountainous roads of the region.

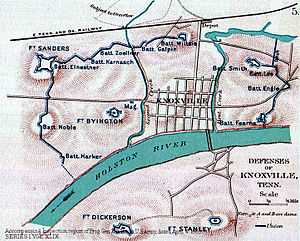

Union engineers commanded by Captain Orlando M. Poe built several fortifications in the form of bastioned earthworks near Knoxville. One was Fort Sanders, just west of downtown Knoxville across a creek valley. It was named for Brig. Gen. William P. Sanders, mortally wounded in a skirmish outside Knoxville on November 18, 1863. The fort, a salient in the line of earthworks that surrounded three sides of the city, rose 70 feet (21 m) above the surrounding plateau and was protected by a ditch 12 feet (3.7 m) wide and 8 feet (2.4 m) deep. An almost vertical wall rose 15 feet (4.6 m) above the ditch. Inside the fort were 12 cannons and 440 men of the 79th New York Infantry.[4]

As a Confederate army under General Braxton Bragg besieged Union forces at Chattanooga, Tennessee, a detachment under the command of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, a trusted subordinate of Robert E. Lee, was sent to Knoxville to prevent Burnside's Army of the Ohio from moving in support of Chattanooga. After Burnside escaped a trap at the Battle of Campbell's Station, his men took up defensive positions around Knoxville and the Siege of Knoxville began on November 17, 1863. Longstreet determined that Fort Sanders was the most appropriate place to attempt a breakthrough of the Union defenses. He initially planned an assault on November 20, but chose to delay while he received reinforcements. His eventual assault was conducted by three infantry brigades, under Brig. Gen. Benjamin G. Humphreys, Brig. Gen. Goode Bryan, and Col. Solon Z. Ruff (commanding Wofford's Brigade).[2]

On November 23, 1863, Longstreet's forces seized Cherokee Heights, a tall bluff south of the Holston River (now called the Tennessee River) from Knoxville, but only about 2,400 yards (2,200 m) from Fort Sanders. Longstreet's original intent was to use artillery to "soften up" Fort Sanders in preparation for a frontal assault; however, at virtually the last minute, he changed the plan to a surprise infantry assault at dawn, hoping that the benefits of surprise would outweigh those of a cannonade. Inexplicably, he squandered the element of surprise by deploying skirmishers forward hours before the assault. Although this movement placed them in good positions for sharpshooting, it clearly revealed his plans to the Union troops.[5]

Battle

The assault, conducted on November 29, 1863, was poorly planned and executed. Longstreet discounted the difficulties of the physical obstacles his infantrymen would face. He had witnessed, through field glasses, a Union soldier walking across the ditch and, not realizing that the man had crossed on a plank, believed that the ditch was very shallow. He also believed that the steep walls could be negotiated by digging footholds, rather than requiring scaling ladders.[6]

The Confederates moved to within 120-150 yards of the salient during the night of freezing rain and snow and waited for the order to attack. Their attack at dawn has been described as "cruel and gruesome by 19th century standards."[2] They were initially confronted by telegraph wire that had been strung between tree stumps at knee height, possibly the first use of such wire entanglements in the Civil War, and many men were shot as they tried to disentangle themselves. When they reached the ditch, they found the vertical wall to be almost insurmountable, frozen and slippery. Union soldiers rained murderous fire into the masses of men, including musketry, canister, and artillery shells thrown as hand grenades. Unable to dig footholds, men climbed upon each other's shoulders to attempt to reach the top. A succession of color bearers was shot down as they planted their flags on the fort. For a brief time, three flags reached the top, those of the 16th Georgia, 13th Mississippi, and 17th Mississippi.[2]

Aftermath

Longstreet undertook his Knoxville expedition, which he came to realize was far too soon, to divert Union troops from Chattanooga and to get away from General Braxton Bragg, with whom he was engaged in a bitter feud. Longstreet reevaluated what was supposed to be a surprise attack and saw how it was poorly planned and executed. Based on comparative casualties, it was one of the most lopsided Union victories of the war. From the beginning of the artillery bombardment until the Confederates broke and retreated, the attack on Fort Sanders lasted about forty minutes. About twenty minutes, or half of that time, were spent in the struggle for control of the parapet. In the brief period of 20 minutes of attacking, General Burnside’s chief engineer, Orlando M. Poe, wrote that he was unaware in the annals of military history where a storming party was so nearly annihilated. The Confederate troops sustained 813 casualties – 129 killed, 458 wounded, and 226 missing. Federal losses inside Fort Sanders amounted to only about 20 men, while another 30 were killed and injured outside the fort by Confederate artillery. While Lieutenant Benjamin reported the Union losses in the fort as five killed and eight wounded, significantly less than their defeated opponent. About 250 prisoners and three flags fell into Union hands.

While Longstreet arranged to withdraw, Burnside sent a flag of truce to allow him to recover his dead and wounded from the field. It was a humanitarian gesture much appreciated by the Confederates. The Union details pulled the dead out on blankets and carried them to a point half way across no-man’s-land for delivery to the Confederates. Many of the bodies had stiffened by this time, and the Federals temporarily leaned them up against the side of the blood-stained ditch. They recovered ninety-six bodies, mostly from inside the ditch, but also from the ground within several yards of the bastion. The Federals delivered slightly more than that number of wounded to the Confederates, for a total of 197. The Confederates identified the bodies of several high-ranking officers such as Solon Z. Ruff and Kennon McElroy.

On the afternoon of November 29, Longstreet changed his mind about disengaging from the Federals at Knoxville when dispatches arrived from Joseph Wheeler. The cavalry general had reached Ringgold, Georgia, on November 25 while making his way back to the Army of Tennessee, only to find that Bragg had been severely beaten at Chattanooga. Bragg asked him to inform Longstreet of the defeat and let him know to rejoin the Army of Tennessee at Dalton or to go back to Virginia if that was not possible. On Dec. 4 Longstreet withdrew from Knoxville and headed toward Rogersville, 65 miles to the northeast. Longstreet’s failure to take Knoxville scuttled his purpose and the Knoxville Campaign was essentially over, with the city remaining in Federal hands for the remainder of the war. This Confederate defeat, plus the loss of the Battle of Chattanooga on November 25, put much of East Tennessee in the Union camp.

Seymour, D. G. (1963). Divided loyalties: Fort Sanders and the Civil War in East Tennessee ([First edition].). University of Tennessee Press. Retrieved April 1, 2015 - See more at: http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015016780093;view=1up;seq=7

Hess, E. J.(2012). The Knoxville Campaign: Burnside and Longstreet in East Tennessee. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from Project MUSE database - http://muse.jhu.edu/books/9781572339248

United States. National Park Service. (n.d.). Battle Summary: Fort Sanders, TN. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from http://www.nps.gov/abpp/battles/tn025.htm

Taylor, P. (2013, April 1). The Knoxville Campaign: Burnside and Longstreet in East Tennessee. Book Review By Earl J. Hess. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from http://www.civilwarnews.com/reviews/2013br/april/knoxville-hess-bw03-09.html

Battlefield today

The Fort Sanders area became the site of many Victorian homes that were built approximately three decades later. Several, especially those located on the uphill sides of streets, are most impressive; some have been restored in recent decades. A few were incorporated into the grounds of the 1982 World's Fair. Many more have been divided into apartments and are rented out to University of Tennessee students. The author James Agee was from this area; the exteriors for the motion picture version of All the Way Home were shot outside one of the more palatial homes, which has since burned. Agee's novel, A Death in the Family, ends with Agee ("Rufus" in the novel) and his uncle conversing while looking out over the ruins of Fort Sanders.

Notes

References

- Alexander, Edward P. Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative. New York: Da Capo Press, 1993. ISBN 0-306-80509-X. First published 1907 by Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Korn, Jerry, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Fight for Chattanooga: Chickamauga to Missionary Ridge. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4816-5.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

- National Park Service battle description

- CWSAC report update

Further reading

- Taylor, Paul. Orlando M. Poe: Civil War General and Great Lakes Engineer. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1-60635-040-9.

- Seymour, Digby Gordon. Divided Loyalties: Fort Sanders and the Civil War in East Tennessee. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1963. OCLC 3519867.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Fort Sanders. |