Battle of Arras (1914)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

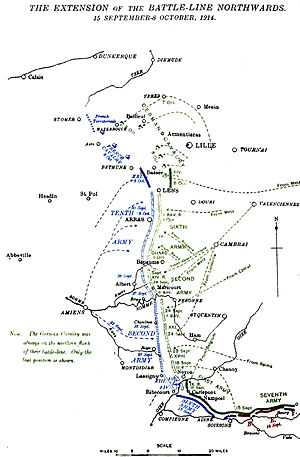

The Battle of Arras (also known as the First Battle of Arras, 1–4 October 1914), was an attempt by the French Army to outflank the German Army, which was attempting to do the same thing during the "Race to the Sea", a misleading term for reciprocal attempts by both sides, to exploit conditions created during the First Battle of the Aisne.[Note 1] At the First Battle of Picardy (22–26 September) each side had attacked expecting to advance round an open northern flank and found instead that troops had arrived from further south and extended the flank northwards.

The Tenth Army, led by General Louis Maud'huy, attacked advancing German forces on 1 October and reached Douai, where the German 6th Army under Crown Prince Rupprecht counter-attacked, as three corps of the German 1st, 2nd and 7th armies attacked further south. The French were forced to withdraw towards Arras and Lens was occupied by German forces on 4 October. Attempts to encircle Arras from the north were defeated and both sides used reinforcements to try another flanking move further north at the Battle of La Bassée (10 October – 2 November). The reciprocal flanking moves ended in Flanders, when both sides reached the North Sea coast and then attempted breakthrough attacks during the First Battle of Flanders.[Note 2]

Background

Strategic developments

On 28 September, Falkenhayn ordered that all available troops were to be transferred to the 6th Army, for an offensive on the existing northern flank by the IV, Guard and I Bavarian corps near Arras, an offensive by the II Cavalry Corps on the right flank of the 6th Army, across Flanders to the coast and an acceleration of the operations at the Siege of Antwerp, before it could be reinforced.[10][Note 3] Rupprecht intended to halt the advance of the French on the west side of Arras and conduct an enveloping attack around the north of the city.[10]

Prelude

Battle of Albert, 25–29 September

On 21 September Falkenhayn had decided to concentrate the 6th Army near Amiens, to attack westwards to the coast and then envelop the French northern flank south of the Somme. The offensive by the French Second Army forced Falkenhayn to divert the XXI Corps and I Bavarian Corps as soon as they arrived, to extend the front northwards from Chaulnes to Péronne on 24 September and drive the French back over the Somme. On 26 September, the Second Army dug in on a line from Lassigny to Roye and Bray sur Somme and German cavalry moved north, to enable the II Bavarian Corps to occupy the ground north of the Somme. On 27 September, the German cavalry (Von der Marwitz), drove back the 61st and 62nd Reserve divisions of General Joseph Brugère, who had replaced General Albert d'Amade, to clear the front for the XIV Reserve Corps to link with the right flank of the II Bavarian Corps. The French Subdivision d'Armée began to assemble at Arras and Maud'huy found that instead of making another attempt to get round the German flank, the subdivision was menaced by a German offensive.[12]

The II Bavarian and XIV Reserve corps, pushed back a French Territorial division from Bapaume and advanced towards Bray sur Somme and Albert.[12] From 25–27 September, the French XXI and X corps north of the Somme, with support on the right flank by the 81st, 82nd, 84th and 88th Territorial divisions under Brugère and the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 10th Cavalry divisions of the Cavalry Corps (General Conneau) to the south-east of Arras, defended the approaches to Albert. On 28 September, the French were able to stop the German advance, on a line from Maricourt to Fricourt and Thiépval. The German cavalry was stopped in the vicinity of Arras by the French cavalry. On 29 September, Joffre added X Corps which was at Acheux, 20 miles (32 km) north of Amiens, the Cavalry Corps which was south-east of Arras and a provisional corps under General Victor d'Urbal, of the 70th and 77th Reserve divisions, one in Arras and the other in Lens, to the new Tenth Army.[13]

Battle

30 September – 1 October

A French division arrived at Arras on 30 September and repulsed a German attack at the Cojeul river and high ground near Monchy-le-Preux on 1 October. The French were then slowly pushed back from Guémappe, Wancourt and Monchy-le-Preux, until the arrival of X Corps.[14] The French XI Corps was withdrawn from the Ninth Army and sent to Amiens; by 1 October two more corps, three infantry and two cavalry divisions had been sent northwards to Amiens, Arras, Lens and Lille, which increased the Second Army to eight corps, along a front of 100 kilometres (62 mi). Joffre ordered Castelnau to cease attempts to outflank the Germans opposite and operate defensively. From the northern corps of the Second Army and the Territorial and cavalry divisions nearby, Joffre created a Subdivision d'Armée under the command of General Louis de Maud'huy. The Subdivision advanced on Arras, with the gap south to the Second Army, held by the Territorial divisions.[10] Maud'huy was ready to begin an attack to the south-east past Arras and Lens, under the impression that the Subdivision was opposed only by a cavalry screen, rather than three German corps which were preparing to attack.[15]

The westward advance of the XIV Reserve Corps, from Bapaume to Albert and Amiens, was stopped by French troops east of Albert. Five German cavalry divisions further north, were also confronted French cavalry and infantry, while attempting to guard the XIV Reserve Corps flank. French reinforcements increased the possibility of a reciprocal French outflanking manoeuvre. Agents reported the massing of French and British troops, between Arras and Lille and that the railways between Lille, Douai and Arras had been protected by an outpost line, from Orchies to Douai and Arras. The 1st Guard Division and IV Corps were moved to the northern flank of the XIV Reserve Corps, to allow some of the cavalry divisions to redeploy. The I Bavarian Reserve Corps (General Karl von Fasbender), was withdrawn from Lorraine and moved to Cambrai and Valenciennes, intended to advance from Douai, in another attempt to outflank the French. The corps began to reach Artois on 30 September and before noon, was ordered to advance with all of the units which had arrived, to reach Douai before dark. Five battalions of the 1st Bavarian Reserve Division advanced north-west from Cambrai and parts of the 5th Bavarian Reserve Division left Denain heading westwards, also for Douai.[16]

The 5th Bavarian Reserve Division advance was stopped by French troops at Lewarde, 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) short of Douai, until the village was captured in the evening, after which the division stopped for the night. The 1st Bavarian Reserve Division battalions also came within 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) of Douai, after overcoming French troops at Cantin and Raucourt. Behind the advanced battalions, the rest of the corps arrived during the day. Both divisions were ordered to capture the town next day and occupy high ground to the west. The inner units were to pin down French troops in Douai, as the flanking units encircled the town and met at Esquerchin to the north-west. The envelopment failed, due to the distance to be travelled and the resistance of French skirmishers, which delayed the German advance. Douai was captured by nightfall and 2,000 French prisoners were collected by 2 October, mainly from Territorial regiments. Allegations that civilians had fired at German troops, led to the town being fined 300,000 Francs.[17] The Guard, IV and I Bavarian corps assembled on a line from Arras to Douai, opposite the Territorial divisions of General Brugère and attacked on 1 October, forestalling the attack being prepared by the Subdivision.[14]

2 October

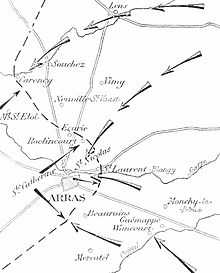

The advance resumed on 2 October, with the 1st Bavarian Reserve Division in the south, attacking through Brebières to St. Laurent and the 5th Bavarian Reserve Division to advance via Izel and Oppy to Bailleul-Sir-Berthoult. It was known that the French 70th Reserve Division was moving south-east, also towards Bailleul and Lens. The French advanced with a left flank guard facing Douai, to link with the 77th Division at Gavrelle and Fresnes. The French divisions had been rushed from the Vosges and were also deployed at short notice. A brigade of the 70th Reserve Division moved towards Fresnes and one advanced south-west to Gavrelle, ready to pause on 2 October and then push outposts southwards. The French moved south in parallel brigade columns, as the Germans moved west in divisional columns. Bavarian Reserve Infantry Brigade 9 of the 5th Bavarian Reserve Division, reached Esquerchin and set flank guards facing north, before advancing on Quiéry la Motte, when French artillery near Izel pinned down the German infantry and destroyed a German artillery battery. French infantry then attacked from Drocourt and forced the German columns to deploy and work forward closer to Izel, to try to overrun the artillery.[18] Bavarian Reserve Infantry Brigade 11 advanced on Beaumont, Drocourt and Bois Bernard, moving the rearguard round to the right flank, which arrived just in time to meet a French attack from Hénin Liétard. Both German brigades attacked again and captured Izel, the heights east of Bois Bernard and Beaumont Station. Later in the evening Drocourt and Fresnoy were captured and Bois Bernard was entered, being captured by dawn on 3 October.[18]

3 October

By the morning of 3 October, the German front line ran from Drocourt to Bois Bernard and Fresnoy. To the south-east, Bavarian Reserve Infantry Brigade 9 attack on Neuvireul was repulsed by small-arms and heavy artillery-fire from Acheville. The brigade dug in between Izel and Neuvireul. In the 1st Bavarian Reserve Division area to the south, the advance was at first protected on both flanks and advanced to Fresnes unopposed.[19] The advance on Arras continued, supported by artillery moved forward during the night and the Guard, 4th, 7th and 9th Cavalry divisions in the Scarpe valley. The cavalry was to cover a westwards move of the Bavarian divisions, the 5th towards Vimy and Thélus and the 1st to Thélus and St. Laurent. The cavalry were slow to move and the Bavarian infantry were held up by attacks from the north, until the cavalry arrived during the afternoon. Bavarian Reserve Infantry Brigade 9 managed to capture Méricourt after the 9th Cavalry Division arrived, which enabled the rest of the 5th Bavarian Reserve Division to advance and capture Rouvroy and Acheville.[20] Around 11:00 a.m. French patrols slowed the advance and the 5th Bavarian Reserve Division put flank guards out on the right for the advance on Gavrelle. French troops in Oppy engaged the Germans with small-arms and artillery-fire, which delayed the Germans until the success of a costly attack against Oppy and Neuvireuil.[19]

Costly German attacks were made on Beaurains, Mercatel and the Arras suburbs of St. Laurent-Blangy and St. Nicolas, which were repulsed and forced the Germans to move northwards.[14] An evening attack by three battalions on Arleux failed, which left the French position from Arleux to Bailleul and Point de Jour intact. More orders arrived to press the advance and an improvised Group Hurt, took over flank protection to the north and responsibility for the advance from Méricourt to Avion; Group Samhaber was ordered to capture Vimy. The flank attack by the French 70th Reserve Division had been repulsed but the advance reached only Drocourt and Gavrelle instead of St. Laurent and Bailleul.[19] The disorganisation in the 5th Bavarian Reserve Division, which had been caused by the urbanised landscape and the vigour of the French defence, was not remedied by the ad hoc groups and worsened on 4 October.[20] The right flank of X Corps of the Subdivision and left flank of the Territorial divisions to the south became separated, prompting Castelnau and Maud'huy to recommend a retreat.[21]

4 October

On 4 October, Joffre made the Subdivision d'Armée independent as the Tenth Army and told Castelnau to keep the Second Army in position, relying on the increasing number of French troops arriving further north to divert German pressure.[21] Foch was appointed as a deputy to Joffre, with responsibility for the northern area of operations, the Territorial divisions, the Second and Tenth armies, which were combined in the Groupe Provisoire du Nord (GPN).[22][Note 4] A 4-kilometre (2.5 mi) gap separated the two 5th Bavarian Reserve Division objectives and a battalion sent to capture Avion disappeared in the dark. An attack by a second battalion began at 6:00 a.m. and quickly succeeded; the rest of the brigade advanced soon after but was engaged west of Avion, by French infantry and artillery firing from Lens and Givenchy. One battalion reached the Lens–Arras road but then managed to advance only another 400 metres (440 yd) before dark. A desperate night attack then captured the wooded hill (Gießlerhöhe) between Souchez and Givenchy, before dawn on 5 October. Group Hurt arrived at dawn, paused at a wood near Liévin and then attacked towards a wood (now Bois de l'Abîme) 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) north-east of Souchez. A cavalry regiment had moved forward independently to high ground west of Angres by 10:30 p.m., calling out to civilians that they were British cavalry.[24] German troops entered Lens, which had been held by a group of French cyclists and a dismounted brigade of the 5th Cavalry Division.[14]

The progress of Group Hurt assisted Group Samhaber further south, to capture Acheville before daybreak, despite a determined French defence and then press on beyond two more defence lines. The German advance was stopped 800 metres (870 yd) short of the railway embankment east of Vimy. New orders arrived for the troops to press on, as it was mistakenly believed that the French were withdrawing but the German infantry made no attempt to advance in daylight, over open ground and without artillery support. Another order arrived at 5:00 p.m., to cross the embankment, take the ridge and Telegraphenhöhe (Telegraph Hill, now Hill 139) to no effect. Later on, after sharing out a large quantity of wine captured at Bois Bernard, an attack began at 10:00 p.m. and reached the embankment after thirty minutes. The advance continued up the ridge south of Vimy but missed La Folie (Hill 140) in the dark and ended up on Telegraphenhöhe but French troops had already retired from Vimy and the hill.[25]

Group Leibrock captured Arleux at 3:00 a.m. on 4 October, made a costly advance to Willerval and then at 8:30 a.m., was held up at the railway embankment and the village of Farbus until dark. As the units further north advanced, the Group was able to advance through Farbus and reach Telegraphenhöhe around midnight. The 5th Bavarian Reserve Division had managed a considerable advance, despite increasing French resistance, casualties and fatigue but Vimy Ridge had not been captured apart from Telegraphenhöhe. The 1st Bavarian Reserve Division had hardly moved, all its attacks on Bailleul having failed, causing a gap to appear between the divisions. It was hoped that German cavalry divisions would be able to advance on 5 October and that the 7th Cavalry Division would manage to turn the French northern flank. An advance in the north was ordered for an advance on Notre Dame de Lorette (Hill 165), which took the chapel unopposed at 6:00 a.m. as the rest of Group Hurt concentrated between Angres, Souchez and Givenchy. (French artillery began a bombardment of the Lorette Spur, which continued into 1915.)[26]

Aftermath

Analysis

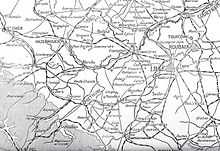

The French had been able to use the undamaged railways behind their front to move troops more quickly than the Germans, who had to take long detours, wait for repairs to damaged tracks and replace rolling stock. The French IV Corps moved from Lorraine on 2 September in 109 trains and had assembled by 6 September.[27] The French had been able to move troops in up to 200 trains per day and use hundreds of motor-vehicles which were co-ordinated by two staff officers, Commandant Gérard and Captain Doumenc. The French used Belgian and captured German rail wagons and the domestic telephone and telegraph systems.[28] The initiative held by the Germans in August was not recovered as all troop movements to the right flank were piecemeal. Until the end of the Siege of Maubeuge (24 August – 7 September) only the single line from Trier to Liège, Brussels, Valenciennes and Cambrai was available and had to be used to supply the German armies on the right, as the 6th Army travelled in the opposite direction, limiting the army to forty trains a day, which took four days to move a corps. Information on German troop movements from wireless interception, enabled the French to forestall German moves but the Germans had to rely on reports from spies, which were frequently wrong. The French resorted to more cautious infantry tactics, using cover to reduce casualties and a centralised system of control, as the German army commanders followed contradictory plans. The French did not need quickly to obtain a decisive result and could concentrate on preserving the French army.[29]

Local operations

5–6 October

Foch arrived on 5 October, in command of all French forces north of the Oise and ordered the Tenth Army to end the fighting withdrawal and regain the initiative. Hasty counter-attacks were made from the area of La Folie, which quickly bogged down and soon after, parties of French troops were seen retreating from Vimy Ridge, through Neuville St. Vaast (Neuville) and south of Carency. The Bavarians were ordered to pursue the French, Group Hurt to a line from Souchez to Carency and Camblain, while Group Samhaber advanced through Neuville St. Vaast and St. Eloi to Acq. As soon as the moves began, French artillery-fire slowed the advance and Group Hurt was stopped at the east end of Carency and the higher ground to the south. Group Samhaber dug in around Souchez and on the Lorette Spur the infantry and cavalry dug in until the arrival of the 7th Cavalry Division. As the German advance had closed on Arras, the French defence became more determined and on Telegraphenhöhe, the Bavarians were counter-attacked all day. At 7:00 a.m. Zouaves made a costly counter-attack north of Thélus and when the Bavarians attempted to advance they were engaged from the village. Eventually, the capture of Thélus enabled Neuville to be occupied unopposed but a new French defensive position was found at La Targette.[30]

The 1st Bavarian Reserve Division managed to capture Bailleul, which brought both divisions level late on 5 October, ready for a broader-front advance in the morning. Group Hurt was ordered to attack towards Camblain again, protected on the northern flank by cavalry. The Lorette Spur was a dominating position, which gave an occupant observation over much of the locality but the steep, wooded, north and east slopes gave cover to an attacker and artillery was difficult to bring to bear. The French could also fire on the spur from three sides. Should the Bavarians withdraw, the area of Ablain, Carency and Souchez would become untenable and a retirement was rejected. A further advance was not possible, because the cavalry had not arrived by 6 October and the 1st Bavarian Reserve Division was still further back around Bailleul and Point de Jour. The corps headquarters sent new orders at 6:00 a.m. for the 5th Division to become a flank guard in the north, as all available troops attacked Arras. Group Hurt was to mask Ablain and cut the roads from the north. Group Samhaber was to attack to the south, capture the crossroads north of Ecurie and advance on Arras. the 1st Division was to attack at the same time from the west to a line from Roclincourt to St. Laurent as IV Corps and the Guard Corps attacked from the south.[31]

The 7th and 9th Cavalry divisions operating north of the Lorette Spur managed to hold on against probing attacks and bombardments from the north, south-west and south. The attack towards Arras faltered against increasing French resistance, a flank guard at Ablain having been attacked all day from the north-west and south-west. Troops were taken from Souchez and the Lorette Spur to cover the gap from Carency to La Targette until dark.[32] On 6 October, Group Samhaber attacked St. Eloi through La Targette, which the French had abandoned but after 600 metres (660 yd) was forced under cover by French troops near Berthonval Farm, until heavy howitzers near La Folie managed to hit the St. Eloi church tower and positions around the farm. The Bavarians were redirected southwards towards Ecurie and were then stopped near La Targette for the rest of the day, by French troops well dug in at Maison Blanche. At 6:00 p.m. a rumour that German troops were in Arras, led to orders to attack again and a cancellation two hours later. In the 1st Bavarian Reserve Division area, the troops west of Bailleul and Thélus attacked Roclincourt at 9:00 a.m. but were slowed on open ground by French artillery fire and two days without food and water.[33] The 1st Division commander ordered that the attack must continue, to keep up with the 5th Division but by night the division was still 1,200 metres (1,300 yd) short of Roclincourt and dispersed over a wide area, which the French exploited to get behind parties of troops and inflict many casualties. After dark the Bavarians managed to inch forward to within 500 metres (550 yd) of Roclincourt and 300 metres (330 yd) of a different Maison Blanche.[34]

7–9 October

Ambitious orders were issued for 7 October, to advance north of Arras to Petit Servin, Mont St. Eloi and Maroeuil, supported by attacks from the east by the 1st Bavarian Reserve Division, IV Corps from the south-east and the Guard Corps from the south. The arrival of the XIV Corps to the north ended the chronic problem of flank security but to the south exhaustion and the need to close gaps and resist French counter-attacks from reinforcements which arrived during the day. Group Hurt in the north managed to repulse French attacks but could not advance and was severely bombarded on the Lorette Spur, which forced some temporary retirements towards Carency. Group Samhaber failed to get forward to St. Eloi and no advance was possible towards Roclincourt, after the French Tenth Army had issued orders to X Corps and the 77th Division to hold their positions at all costs.[34]

On 8 October a special attack on Roclincourt was ordered for 4:00 a.m. to prepare the way for another outflanking move from the north. Despite elaborate arrangements, only a small amount of ground along the Bailleul–Arras road was taken and the attack on Roclincourt was abandoned as a costly failure, one battalion being reduced to 240 riflemen. Attacks on the Lorette Spur towards Petit Severin failed and attacks by the 13th Division of XIV Corps in the north made no progress. During the afternoon the French made a general attack from Ablain to Neuville which forced the Germans and Bavarians to rush forward every spare man to plug gaps between units. At Carency the French 43rd Division took the west end and was then stopped by reinforcements rushed from Vimy who stabilised the front and took prisoner 90 men of the 31st Chasseurs. The 13th Division reached the Lorette Spur and dug in, which by nightfall meant that the German positions ran from Aix Noulette to the spur, Bois de Bouvigny, west of Ablain, Carency, La Targette, Maison Blanch, Neuville, north of Ecurie, east of Roclincourt and south to the Scarpe valley. These positions marked the end of the battle of manoeuvre in the area, local attempts to advance were defeated by the French and by 9 October, German reliefs in line were under way, to reorganise the mixture of units, which took a week.[35]

Subsequent operations

First Battle of Flanders

To the north, the I and II Cavalry corps attacked between Lens and Lille and were quickly repulsed and forced back behind the Lorette Spur. Next day the cavalry was attacked by the first troops of the French XXI Corps advancing from Béthune.[Note 5] On 8 October the German XIV Corps arrived from Mons and took over from the cavalry, which were sent north to resume their attack from La Bassée and Armentières. The IV Cavalry Corps had moved north of Lille and on 8 October reached Ypres and then turned south-west towards Hazebrouck, where they were met by the new French I Cavalry Corps (General Antoine de Mitry) and forced to retire to Bailleul. By 9 October, the defensive lines established on the Aisne in September had been extended to the west and north to within 30 miles (48 km) of Dunkirk and the North Sea coast.[23] On 3 October, Joffre formed the Tenth Army under General de Maud'huy to reinforce his left and prevent its envelopment. The XXI Corps arrived from Champagne and the 13th Division assembled west of Lille.[36]

Lille 1914

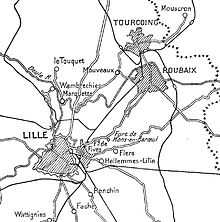

The armament of the Lille fortress zone in 1914, consisted of 446 guns and 79,788 shells (including 3,000 × 75 mm shells), 9,000,000 rounds of rifle ammunition and 12 × 47 mm guns, which had been sent from Paris. During the Battle of Charleroi (21 August), General d'Amade garrisoned the area from Maubeuge to Dunkirk with a line of Territorial divisions. The 82nd Division held the area between the Escaut and the Scarpe, with advanced posts at Lille, Deulemont and Tournai, just over the Belgian border. The Territorials dug in but on 23 August, the BEF retreated from Mons and the Germans drove the 82nd Territorial Division out of Tournai. The German advance reached Roubaix and Tourcoing before a counter-attack by the 83rd and 84th regiments reoccupied Tournai during the night. Early on 24 August, the 170th Brigade organized the defence of the bridges over the Escaut but around noon, the Territorials were forced back by a German attack. The Mayor of Lille requested that the city be declared open and at 5:00 p.m., the Minister of War ordered the garrison to leave the city and move between La Bassée and Aire-sur-la-Lys.[37][Note 6]

On 25 August, the German 1st Army reached the outskirts of Lille and General Herment withdrew the garrison. Maubeuge to the south was defended by 45,000 men and the Belgian army was still defending Antwerp to the north. On 2 September, German detachments entered Lille and left three days later, the town was intermittently occupied by patrols, guarding the right flank of the 1st Army. After the German retreat from the Marne and the First Battle of the Aisne (13 September – 28 September) the northward manoeuvre known as the Race for the Sea commenced and on 3 October, Joffre formed the 10th Army under General de Maud'huy, to reinforce the northern flank of the French armies. The 13th Division of XXI Corps arrived from Champagne and detrained to the west of Lille. On the morning of 4 October, chasseurs battalions of the 13th Division moved to positions north and east of Lille.[37]

The 4th Chasseur Battalion advanced towards the suburb of Fives but was engaged by small-arms fire as it left the Lille ramparts. The chasseurs drove the Germans back from the railway station and fortifications, taking several prisoners and some machine-guns. North of the town, the French met more German patrols near Wambrechies and Marquette and the 7th Cavalry Division skirmished in the neighbourhood of Fouquet. The new Lille garrison, consisting of Territorial and Algerian mounted troops, took post to the south at Faches and Wattignies, linking with the rest of the 13th Division at Ronchin. A German attack reached the railway and on 5 October, a French counter-attack recaptured Fives, Hellemmes, Flers, the fort of Mons-en-Baroeuil and Ronchin; to the west, cavalry engagements took place along the Ypres Canal. On 6 October, the 13th Division left two chasseur battalions at Lille as XXI Corps moved south towards Artois and French cavalry near Deulemont repulsed a German attack. On 7 October, the chasseur battalions were withdrawn and the defence of Lille reverted to the Territorial and Algerian troops. From 9–10 October, the I Cavalry Corps engaged German troops between Aire-sur-la-Lys and Armentieres but failed to re-open the road to Lille.[40]

At 10:00 a.m. on 9 October, a German aeroplane appeared over Lille and dropped two bombs on the General Post Office. In the afternoon, all men from 18–48 were ordered to the Béthune Gate, with instructions to leave Lille immediately.[40] Civilians from Lille, Tourcoing, Roubaix and neighbouring villages, left on foot for Dunkirk and Gravelines. Several died on the way of exhaustion and others were taken prisoners by German Uhlans. The last train left Lille at dawn on 10 October, an hour after German artillery had begun to fire on the neighbourhood of the station, Prefecture and the Palais des Beaux Arts. At 9:00 a.m. on 11 October, after a lull since the previous afternoon, the bombardment resumed until 1:00 a.m. and then continued intermittently. On 12 October, the garrison capitulated, by when 80 civilians had been killed, many fires had been started and the vicinity of the railway station was destroyed. Five companies of Bavarian troops entered the town, followed throughout the day by cavalry, artillery and more infantry.[41]

First Battle of Artois

After studying the possibilities for an offensive the Operations Bureau of the French army recommended to Joffre a dual offensive, with attacks in Artois and Champagne, to crush the German salient in France. Despite shortages of equipment, artillery and ammunition, which led Joffre to doubt that a decisive success could be obtained, it was impossible to allow the Germans to concentrate their forces in Russia. Principal attacks were to be made in Artois by the Tenth Army towards Cambrai and by the Fourth Army in Champagne, with supporting attacks elsewhere. The objectives were to deny the Germans an opportunity to move troops and to break through in several places, to force the Germans to retreat.[42] The Tenth Army was to capture Vimy Ridge, to dominate the Douai plain and induce a German retirement. From north to south, XXI Corps was to break through at Souchez and capture Givenchy, XXXIII Corps was to capture the ridge and 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) south, X Corps would attack north-east from Arras, to cover the southern flank of XXXIII Corps. Artillery support for the offensive would consist of 632 guns, including 110 heavy, by 25 December. As a deception, the French sapped forward to reduce the width of no man's land to 150 metres (160 yd), at all places on the Western Front where an attack was feasible.[43]

Foch ordered Maud'Huy to slow the planned pace of the offensive, of successive attacks on several days, to ensure artillery support for the infantry, which was intended to substitute shells for lives. The offensive was fought from (17 December 1914 – 13 January 1915) but despite the careful preparations achieved little. Artillery support was insufficient and rains turned the battlefield into a morass. XXI Corps managed a short advance and captured about 1-kilometre (0.62 mi) of the German front trench and X Corps captured a small area of ground near Arras. The XXXIII Corps attack began next day and was equally frustrated by the German defence. Next day the corps concentrated its attack on Carency to little effect until 27 December, when 700 metres (770 yd) of front-line trench was captured, only for most to be lost to a German counter-attack. Bad weather then delayed the offensive and on 5 January, Joffre decided to reinforce the Fourth Army, where the First Battle of Champagne (20 December 1914 – 17 March 1915), had been more successful, with troops from the Tenth Army, the offensive in Artois being officially ended on 13 January.[44]

Notes

- ↑ Writers and historians have criticised the term Race to the Sea and used several date ranges for the period of mutual attempts to outflank the opposing armies on their northern flanks. In 1925, J. E. Edmonds the British Official Historian, used dates of 15 September – 15 October and in 1926 17 September – 19 October.[1][2] In 1929, the fifth volume of Der Weltkrieg the German Official History, described the progress of German outflanking attempts, without labelling them.[3] In 2001, Strachan used 15 September – 17 October.[4] In, 2003 Clayton gave dates from 17 September – 7 October.[5] In 2005, Doughty used the period from 17 September – 17 October and Foley from 17 September to a period from 10–21 October.[6][7] In 2010, Sheldon placed the beginning of the "erroneously named" race, from the end of the Battle of the Marne, to the beginning of the Battle of the Yser.[8]

- ↑ According to the findings of the Battles Nomenclature Committee of 9 July 1920, four simultaneous battles occurred in October and November 1914. The Battle of La Bassée (10 October – 2 November) from the Beuvry–Béthune road to a line from Estaires to Fournes, the Battle of Armentières (13 October – 2 November) from Estaires to the Douve river, the Battle of Messines (12 October – 2 November) from the Douve to the Ypres–Comines Canal and the Battles of Ypres (19 October – 22 November), comprising the Battle of Langemarck (21–24 October), the Battle of Gheluvelt (29–31 October) and the Battle of Nonne Bosschen (11 November), from the Ypres–Comines Canal to Houthulst Forest. J. E. Edmonds, the British Official Historian, wrote that the II Corps battle at La Bassée could be taken as separate but that the other battles from Armentières to Messines and Ypres, were better understood as a battle in two parts, an offensive by III Corps and the Cavalry Corps from 12–18 October, against which the Germans retired and the offensive by the German 6th and 4th armies 19 October – 2 November, which from 30 October mainly took place north of the Lys at Armentières, from when the battles of Armentières and Messines merged with the Battles of Ypres.[9]

- ↑ I Cavalry Corps with the Guard and 4th Cavalry divisions, II Cavalry Corps with the 2nd, 7th and 9th Cavalry divisions and the IV Cavalry Corps of the 3rd, 6th and Bavarian Cavalry divisions.[11]

- ↑ By 6 October, the Second Army front from the Oise to the Somme and the Tenth Army front from Thiepval to Gommecourt, Blaireville, the eastern fringe of Arras, Bailleul, Vimy and Souchez had been stabilised. The cavalry offensive commanded by Marwitz north of the 6th Army, had pushed back the French Territorial divisions to a line between Lens and Lille. On 5 October, Marwitz issued orders for the cavalry to advance westwards to Abbeville on the Channel coast and cut the railways leading south; at the end of 6 October, Falkenhayn terminated attempts by the 2nd Army to break through in Picardy.[23]

- ↑ According to the findings of the Battles Nomenclature Committee of 9 July 1920, four battles occurred simultaneously during October and November 1914. The Battle of La Bassée (10 October – 2 November) from the Beuvry–Béthune road to a line from Estaires to Fournes, the Battle of Armentières (13 October – 2 November) from Estaires to the Douve river, the Battle of Messines (12 October – 2 November) from the Douve to the Ypres–Comines Canal and the Battles of Ypres (19 October – 22 November), comprising the Battle of Langemarck (21–24 October), the Battle of Gheluvelt (29–31 October) and the Battle of Nonne Bosschen (11 November), from the Ypres–Comines Canal to Houthulst Forest. J. E. Edmonds, the British Official Historian, wrote that the II Corps battle at La Bassée could be taken as separate but that the other battles from Armentières to Messines and Ypres, were better understood as a battle in two parts, an offensive by III Corps and the Cavalry Corps from 12–18 October, against which the Germans retired and the offensive by the German 6th and 4th armies 19 October – 2 November, which from 30 October mainly took place north of the Lys at Armentières, from when the battles of Armentières and Messines merged with the Battles of Ypres.[9]

- ↑ Lille lies between the rivers Lys, Escaut and Scarpe, in the plain before the hills of Artois, between Maubeuge and the port of Dunkirk. In 1873, General Séré de Rivières, Director of the Engineering Section at the Ministry of War, began a programme of fortress-building to reorganize the defences of the northern frontier, with Lille as one of the pivots.[38] At the end of the century, the fortifications were allowed to become derelict and by July 1914, 3,000 gunners and nearly a third of the guns had been removed. On 1 August the Governor, General Lebas, received orders to consider Lille an open city but on 21 August his successor, General Herment, increased the garrison from 15,000–25,000 and then to 28,000 men, drawing units from each regiment in the 1st Region.[39]

Footnotes

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 27–100.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, pp. 400–408.

- ↑ Reichsarchiv 1929, p. 14.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 266–273.

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p. 98.

- ↑ Foley 2005, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Sheldon 2010, p. x.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Edmonds 1925, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Strachan 2001, p. 268.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, p. 404.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Edmonds 1926, pp. 401–402.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, pp. 402–403.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Michelin 1919, p. 6.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, pp. 403–404.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Sheldon 2008, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Sheldon 2008, pp. 6, 8.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Sheldon 2008, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Strachan 2001, pp. 268–269.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 269.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Edmonds 1926, p. 405.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p. 100.

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p. 62.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 265–266.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, pp. 15–16, 17–18.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, pp. 19.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, pp. 19–21.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Sheldon 2008, pp. 22.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Michelin 1919, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Michelin 1919c, p. 5.

- ↑ Michelin 1919c, p. 3.

- ↑ Michelin 1919c, p. 4.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Michelin 1919c, p. 6.

- ↑ Michelin 1919c, p. 7.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp. 126–128.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp. 128–130.

References

- Books

- Arras, Lens–Douai and the Battles of Artois (PDF). Clermont-Ferrand: Michelin & Cie. 1919. OCLC 154114243. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Clayton, A. (2003). Paths of Glory: The French Army 1914–18. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35949-1.

- Der Herbst-Feldzug 1914: Im Westen bis zum Stellungskrieg, im Osten bis zum Rückzug. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Militärischen Operationen zu Lande I (Die Digitale Landesbibliothek Oberösterreich 2012 ed.). Berlin: Mittler & Sohn. 1929. OCLC 838299944. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-67401-880-X.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914 (PDF). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Foley, R. T. (2005). German Strategy and the Path to Verdun : Erich Von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Lille, Before and During the War (PDF). Michelin's Illustrated Guides to the Battlefields (1914–1918). London: Michelin Tyre Co. 1919. OCLC 629956510. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- Sheldon, J. (2010). The German Army at Ypres 1914 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-113-0.

- Sheldon, J. (2008). The German Army on Vimy Ridge 1914–1917. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 1-84415-680-X.

- Strachan, H. (2001). To Arms. The First World War I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

- Websites

- "Battle of Arras". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 5 August 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- "Battles: The Battle of Arras, 1914". FirstWorldWar.net. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

Further reading

- Books

- Foch, F. (1931). Mémoire pour servir à l'histoire de la guerre 1914–1918: avec 18 gravures hors-texte et 12 cartes [The Memoirs of Marshal Foch] (PDF) (in French) (Heinemann [Translated by T. Bentley Mott] ed.). Paris: Plon. OCLC 86058356. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Raleigh, W. A. (1969) [1922]. The War in the Air: Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (PDF) I (Hamish Hamilton ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 785856329. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Sheldon, J. (2005). The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military 2006 ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 1-84415-269-3.

- Encyclopedias

- The Times History of the War (PDF) II. London: The Times. 1914–1922. OCLC 220271012. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Arras (1914). |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||