Bastille Day

| Bastille Day | |

|---|---|

Fireworks at the Eiffel Tower, Paris, Bastille Day 2011.

The aerobatic team of the French Air Force. | |

| Also called |

French National Day (Fête nationale) The Fourteenth of July (Quatorze juillet) |

| Observed by | France |

| Type | National Day |

| Significance | Commemorates the beginning of the French Revolution with the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789,[1][2] and the unity of the French people at the Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790. |

| Celebrations | Military parades, fireworks, concerts, balls |

| Date | 14 July |

| Next time | 14 July 2015 |

| Frequency | annual |

Bastille Day is the name given in English-speaking countries to the French National Day, which is celebrated on 14 July each year. In France, it is formally called La Fête nationale (French pronunciation: [la fɛːt nasjɔˈnal]; The National Celebration) and commonly Le quatorze juillet (French pronunciation: [lə.katɔʁz.ʒɥiˈjɛ]; the fourteenth of July).

The French National Day commemorates the beginning of the French Revolution with the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789,[1][2] as well as the Fête de la Fédération which celebrated the unity of the French people on 14 July 1790. Celebrations are held throughout France. The oldest and largest regular military parade in Europe is held on the morning of 14 July, on the Champs-Élysées in Paris in front of the President of the Republic, French officials and foreign guests.[3][4]

Events and traditions of the day

Nationally.

The Bastille Day Military Parade opens with cadets from the École polytechnique, Saint-Cyr, École Navale, and so forth, then other infantry troops, then motorized troops; aircraft of the Patrouille de France aerobatics team fly above. In recent times, it has become custom to invite units from France's allies to the parade. In 2004 during the centenary of the Entente Cordiale, British troops (the band of the Royal Marines, the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment, Grenadier Guards and King's Troop, Royal Horse Artillery) led the Bastille Day parade in Paris for the first time, with the Red Arrows flying overhead.[5] In 2007 the German 26th Airborne Brigade led the march followed by British Royal Marines. In 2013, Malian soldiers opened the parade, following the Franco-Malian military Operation Serval. Members of the United Nations' MINUSMA forces also took part in the parade, including soldiers from twelve other African countries, notably Chad. United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon attended the parade alongside French President François Hollande.[6]

Locally

At the municipal level, ceremonies are organized in most of communes of France with a traditional speech of the mayor, followed by wreath-laying at war memorial. French honor guard stands before war memorial and holds emblems of his municipality.

History

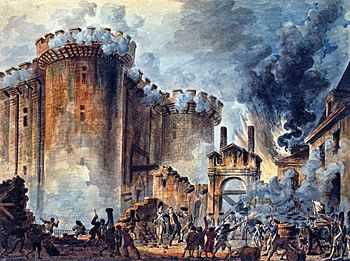

Storming of the Bastille

On 19 May 1789, Louis XVI convened the Estates-General to hear their grievances. The deputies of the Third Estate, representing the common people (the two others were the Catholic Church and nobility), decided to break away and form a National Assembly. On 20 June the deputies of the Third Estate took the Tennis Court Oath, swearing not to separate until a constitution had been established. They were gradually joined by delegates of the other estates; Louis XVI started to recognize their validity on 27 June. The assembly renamed itself the National Constituent Assembly on 9 July, and began to function as a legislature and to draft a constitution.

In the wake of the 11 July dismissal of Jacques Necker (the finance minister, who was sympathetic to the Third Estate), the people of Paris, fearful that they and their representatives would be attacked by the royal army, and seeking to gain ammunition and gunpowder for the general populace, stormed the Bastille, a fortress-prison in Paris which had often held people jailed on the basis of lettres de cachet, arbitrary royal indictments that could not be appealed. Besides holding a large cache of ammunition and gunpowder, the Bastille had been known for holding political prisoners whose writings had displeased the royal government, and was thus a symbol of the absolutism of the monarchy. As it happened, at the time of the attack in July 1789 there were only seven inmates, none of great political significance.

When the crowd—eventually reinforced by mutinous gardes françaises—proved a fair match for the fort's defenders, Governor de Launay, the commander of the Bastille, capitulated and opened the gates to avoid a mutual massacre. However, possibly because of a misunderstanding, fighting resumed. Ninety-eight attackers and just one defender died in the actual fighting, but in the aftermath, de Launay and seven other defenders were killed, as was the 'prévôt des marchands' (roughly, mayor) Jacques de Flesselles.

Shortly after the storming of the Bastille, on 4 August, feudalism was abolished. On 26 August, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was proclaimed.

Fête de la Fédération

The Fête de la Fédération on the 14 July 1790 was a celebration the unity of the French Nation during the French Revolution.The aim of this Celebration was to symbolize Peace one year after the Storming of the Bastille. The event took place on the Champ de Mars, which was at the time far outside Paris. The place had been transformed on a voluntary basis by the population of Paris itself, in what was recalled as the Journée des brouettes ("Wheelbarrow Day").

A mass was celebrated by Talleyrand, bishop of Autun. The popular General Lafayette, as captain of the National Guard of Paris and confidant of the king, took his oath to the constitution, followed by King Louis XVI. After the end of the official celebration, the day ended in a huge four-day popular feast and people celebrated with fireworks, as well as fine wine and running naked through the streets in order to display their great freedom.

Origin of the present celebration

On 30 June 1878, a feast had been arranged in Paris by official decision to honour the French Republic (the event was commemorated in a painting by Claude Monet).[7] On 14 July 1879, another feast took place, with a semi-official aspect; the events of the day included a reception in the Chamber of Deputies, organised and presided over by Léon Gambetta,[8] a military review in Longchamp, and a Republican Feast in the Pré Catelan.[9] All through France, Le Figaro wrote, "people feasted much to honour the storming of the Bastille".[10]

On 21 May 1880, Benjamin Raspail proposed a law to have "the Republic choose the 14 July as a yearly national holiday". The Assembly voted in favour of the proposal on 21 May and 8 June.[11] The Senate approved on it 27 and 29 June, favouring 14 July against 4 August (honouring the end of the feudal system on 4 August 1789). The law was made official on 6 July 1880, and the Ministry of the Interior recommended to Prefects that the day should be "celebrated with all the brilliance that the local resources allow". Indeed, the celebrations of the new holiday in 1880 were particularly magnificent.

In the debate leading up to the adoption of the holiday, Henri Martin, chairman of the French Senate, addressed that chamber on 29 June 1880:

Do not forget that behind this 14 July, where victory of the new era over the ancien régime was bought by fighting, do not forget that after the day of 14 July 1789, there was the day of 14 July 1790.... This [latter] day cannot be blamed for having shed a drop of blood, for having divided the country. It was the consecration of the unity of France.... If some of you might have scruples against the first 14 July, they certainly hold none against the second. Whatever difference which might part us, something hovers over them, it is the great images of national unity, which we all desire, for which we would all stand, willing to die if necessary.

Bastille Day Military Parade

The Bastille Day Military Parade is the French military parade that has been held on the morning of 14 July each year in Paris since 1880. While previously held elsewhere within or near the capital city, since 1918 it has been held on the Champs-Élysées, with the participation of the Allies as represented in the Versailles Peace Conference, and with the exception of the period of German occupation from 1940 to 1944 (when the ceremony took place in London under the command of General de Gaulle).[13] The parade passes down the Champs-Élysées from the Arc de Triomphe to the Place de la Concorde, where the President of the French Republic, his government and foreign ambassadors to France stand. This is a popular event in France, broadcast on French TV, and is the oldest and largest regular military parade in Europe.[3][4] In some years, invited detachments of foreign troops take part in the parade and foreign statesmen attend as guests.

Smaller military parades are held in French garrison towns, including Toulon and Belfort, with local troops.

Bastille Day celebrations in other countries

- Belgium

- Liège celebrates the Bastille Day each year since the end of the First World War, as Liège was decorated by the Légion d'Honneur for its unexpected resistance during the Battle of Liège.

- Czech Republic

- Since 2008, Prague has hosted a French market "Le marché du 14 juillet" offering traditional French food and wine as well as music. The market takes place on Kampa Island, usually between 11 and 14 July.

- Hungary

- Budapest's two-day celebration is sponsored by the Institut de France.[14]

- India

- Bastille Day is celebrated with great festivity in Pondicherry every year.[15] Being an important French colony, Pondicherry celebrates this day with great honor and pride. On the eve of the Bastille Day, retired soldiers engage themselves in parade and celebrate the day with Indian and French National Anthems. On the day, uniformed war soldiers march through the street to honor the French soldiers who were killed in the battles. One can perceive French and the Indian flag flying alongside that project the mishmash of cultures and heritages.

- South Africa

- Franschhoek's week-end festival[17] has been celebrated for the last 15 years. (Franschhoek, or 'French Corner,' is situated in the Western Cape.)

- United Kingdom

- London has a large French contingent, and celebrates Bastille Day at various locations including Battersea Park, Camden Town and Kentish Town.[18]

- Edinburgh continues recalls the days of the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France with its annual Bastille Day celebration, which is often second only those of Paris.

- United States – Over 50 U.S. cities conduct annual celebrations:[19]

- Baltimore has a large Bastille Day celebration each year at Petit Louis in the Roland Park area of Baltimore City.

- Boston has a celebration annually, hosted by the French Cultural Center for over 35 years. Recently, the celebration took place in The Liberty Hotel, a former city jail converted into a boutique hotel, though more often the festivities occur in Boston's Back Bay neighborhood, near the Cultural Center's headquarters. The celebration typically includes francophone musical performers, dancing, and French cuisine.

- Chicago has hosted a variety of Bastille Day celebrations in a number of locations in the city, including Navy Pier and Oz Park. The recent incarnations have been sponsored in part by the Chicago branch of the French-American Chamber of Commerce and by the French Consulate-General in Chicago.

- Dallas's Bastille Day celebration, "Bastille On Bishop", began in 2010 and is held annually on 14 July in the Bishop Arts District of the North Oak Cliff neighborhood, southwest of downtown just across the Trinity River. Dallas' French roots are tied to the short lived socialist Utopian community La Réunion, formed in 1855 and incorporated into the City of Dallas in 1860.

- Houston has a celebration at La Colombe d'Or Hotel. It is hosted by the Consulate General of France in Houston, The French Alliance, the French-American Chamber of Commerce, and the Texan-French Alliance for the Arts.[20]

- Milwaukee's four-day [21] street festival begins with a "Storming of the Bastille" with a 43-foot replica of the Eiffel Tower.

- Minneapolis has a celebration in Uptown with wine, French food, pastries, a flea market, circus performers and bands. Also in the Twin Cities area, the local chapter of the Alliance Française has hosted an annual event for years at varying locations with a competition for the "Best Baguette of the Twin Cities." [22][23]

- Montgomery, Ohio has a celebration with wine, beer, local restaurants' fare, pastries, games and bands.

- New Orleans has multiple celebrations, the largest in the historic French Quarter.[24]

- New York City has numerous Bastille Day celebrations each July, including Bastille Day on 60th Street hosted by the French Institute Alliance Française between Fifth and Lexington Avenues on the Upper East Side of Manhattan,[25] Bastille Day on Smith Street in Brooklyn, and Bastille Day in Tribeca. The Empire State Building is illuminated in blue, white and red.

- Orlando has a boutique Bastille Day street festival that began in 2009 in the Audubon Park Garden District and involves champagne, wine, music, petanque, artists, and street performers.

- Philadelphia's Bastille Day, held at Eastern State Penitentiary, involves Marie Antoinette throwing locally manufactured Tastykakes at the Parisian militia, as well as a re-enactment of the storming of the Bastille.[26]

- Portland Oregon has celebrated Bastille Day with crowds up to 8000, in public festivals at various public parks, since 2001. The event is coordinated by the Alliance Française of Portland.

- Sacramento, California conducts annual "waiter races" in the midtown restaurant and shopping district, with a street festival.

- San Francisco has a large celebration in the city's historic French Quarter in downtown.

- Seattle's Bastille Day Celebration, held at the Seattle Center, involves performances, picnics, wine and shopping.

- St. Louis has annual festivals in both the Soulard neighborhood and the former French village of Carondelet, Missouri which include reenactments of the beheading of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, as well as reconstructed French fur trading posts.

_2010-03-23_02.jpg)

One-time celebrations

- 1979: A concert with Jean Michel Jarre on the Place de la Concorde in Paris attracted one million people, securing an entry in the Guinness Book of Records for the largest crowd at an outdoor concert.

- 1989: France celebrated the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution, notably with a monumental show on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, directed by French designer Jean-Paul Goude. President François Mitterrand acted as host for invited world leaders.

- 1990: A concert with Jarre was held at La Défense in Paris.

- 1994: The military parade was opened by Eurocorps, a newly created European army unit including German soldiers. This was the first time German troops entered in France since 1944, sealing the definitive Franco-German reconciliation.

- 1995: A concert with Jarre was held at the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

- 1998: Two days after the French football team became World Cup champions, huge celebrations took place nationwide.

- 2004: To commemorate the centenary of the Entente Cordiale, the British led the military parade with the Red Arrows flying overhead.

- 2007: To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome, the military parade was led by troops from the 26 other EU member states, all marching at the French time.

- 2014: To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the beginning to the First World War, representatives of 80 countries who fought during this conflict were invited to the ceremony. The military parade was opened by 80 flags representing each of these countries.

See also

- Bastille Day Military Parade

- Opération 14 juillet

- Public Holidays in France

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Bastille Day – 14th July". Official Website of France.

A national celebration, a re-enactment of the storming of the Bastille [...] Commemorating the storming of the Bastille on 14th July 1789, Bastille Day takes place on the same date each year. The main event is a grand military parade along the Champs-Élysées, attended by the President of the Republic and other political leaders. It is accompanied by fireworks and publics dances in towns throughout the whole of France.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "La fête nationale du 14 juillet". Official Website of Elysée.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Champs-Élysées city visit in Paris, France — Recommended city visit of Champs-Élysées in Paris". Paris.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Celebrate Bastille Day in Paris This Year". Paris Attractions. 2011-05-03. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑

- ↑ "14-Juillet : les troupes africaines à l'honneur sur les Champs-Elysées". Le Monde.fr (in French). 14 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ Adamson, Natalie (2009-08-15). Painting, politics and the struggle for the École de Paris, 1944-1964. Ashgate. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7546-5928-0. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ↑ Nord, Philip G. (2000). Impressionists and politics: art and democracy in the nineteenth century. Psychology Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-415-20695-2. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ↑ Nord, Philip G. (1995). The republican moment: struggles for democracy in nineteenth-century France. Harvard University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-674-76271-8. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ↑ "Paris Au Jour Le Jour". Le Figaro. 16 July 1879. p. 4. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

On a beaucoup banqueté avant-hier, en mémoire de la prise de la Bastille, et comme tout banquet suppose un ou plusieurs discours, on a aussi beaucoup parlé.

- ↑ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen; Reichardt, Rolf (1997). The Bastille: a history of a symbol of despotism and freedom. Duke University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-8223-1894-1. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ↑ Le Quatorze Juillet at the Greeting Card Universe Blog

- ↑ Défilé du 14 juillet, des origines à nos jours (14 July Parade, from its origins to the present)

- ↑ "Bastille Day 2007 - Budapest | Budapest Resources...the ORIGINAL Expat Service Center". Budapestresources.com. 2011-07-14. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Puducherry Culture". Government of Puducherry. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ "Remuera Business Association – Bastille Day Street Festival".

- ↑ "Bastille Day Festival at Franschhoek". Franschhoek.co.za. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Bastille Day London – Bastille Day Events in London, Bastille Day 2011". Viewlondon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Bastille Day Map. Interactive Map Bastille Day Locations in the U.S.

- ↑ "Texan French Alliance for the Arts - 2011 Bastille Day". Texanfrenchalliance.org. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Bastille Days | East Town Association | Milwaukee, WI". Easttown.com. 2014-07-12. Retrieved 2014-07-23.

- ↑ "2009 Bastille Day Celebration - Alliance Française, Minneapolis". Yelp. 11 July 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ "Bastille Day celebrations, 2011". Consulat Général de France à Chicago. 14 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ Martha Carr, The Times-Picayune (2009-07-13). "Only in New Orleans: Watch locals celebrate Bastille Day in the French Quarter". NOLA.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Bastille Day on 60th Street, New York City | Sunday, July 15, 2012 | 12–5pm | Fifth Avenue to Lexington Avenue". Bastilledayny.com. 2011-07-10. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ ESP :: Eastern State Penitentiary Website

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bastille Day. |

- Bastille Day – 14 July - Official French website (in English)

- The French Revolution - In a Nutshell

- Bastille Day history

- Bastille Day 2011 — slideshow by Life magazine

- The 2011 Bastille Day Military Parade, video broadcast by the French Minstry of Defence