Barley

| Barley | |

|---|---|

| |

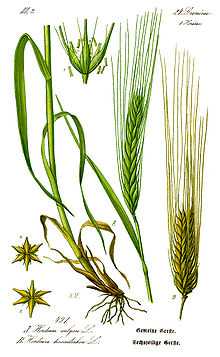

| Drawing of Barley | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Monocots |

| (unranked): | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Tribe: | Triticeae |

| Genus: | Hordeum |

| Species: | H. vulgare[1] |

| Binomial name | |

| Hordeum vulgare L. | |

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain. It was one of the first cultivated grains and is now grown widely. Barley grain is a staple in Tibetan cuisine and was eaten widely by peasants in Medieval Europe. Barley has also been used as animal fodder, as a source of fermentable material for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods. It is used in soups and stews, and in barley bread of various cultures. Barley grains are commonly made into malt in a traditional and ancient method of preparation.

In a 2007 ranking of cereal crops in the world, barley was fourth both in terms of quantity produced (136 million tons) and in area of cultivation (566,000 square kilometres or 219,000 square miles).[2]

Etymology

The Old English word for 'barley' was bære, which traces back to Proto-Indo-European and is cognate to the Latin word farina "flour". The direct ancestor of modern English "barley" in Old English was the derived adjective bærlic, meaning "of barley".[3] The first citation of the form bærlic in the Oxford English Dictionary dates to around 966 AD, in the compound word bærlic-croft.[4] The underived word bære survives in the north of Scotland as bere, and refers to a specific strain of six-row barley grown there.[5] The word barn, which originally meant "barley-house", is also rooted in these words.[3]

Biology

_-_United_States_National_Arboretum_-_24_May_2009.jpg)

Barley is a member of the grass family. It is a self-pollinating, diploid species with 14 chromosomes. The wild ancestor of domesticated barley, Hordeum vulgare subsp. spontaneum, is abundant in grasslands and woodlands throughout the Fertile Crescent area of Western Asia and northeast Africa, and is abundant in disturbed habitats, roadsides and orchards. Outside this region, the wild barley is less common and is usually found in disturbed habitats.[6] However, in a study of genome-wide diversity markers, Tibet was found to be an additional center of domestication of cultivated barley.[7]

Domestication

Wild barley has a brittle spike; upon maturity, the spikelets separate, facilitating seed dispersal. Domesticated barley has nonshattering spikes, making it much easier to harvest the mature ears.[6] The nonshattering condition is caused by a mutation in one of two tightly linked genes known as Bt1 and Bt2; many cultivars possess both mutations. The nonshattering condition is recessive, so varieties of barley that exhibit this condition are homozygous for the mutant allele.[6]

Two-row and six-row barley

Spikelets are arranged in triplets which alternate along the rachis. In wild barley (and other Old World species of Hordeum), only the central spikelet is fertile, while the other two are reduced. This condition is retained in certain cultivars known as two-row barleys. A pair of mutations (one dominant, the other recessive) result in fertile lateral spikelets to produce six-row barleys.[6] Recent genetic studies have revealed that a mutation in one gene, vrs1, is responsible for the transition from two-row to six-row barley.[8]

Two-row barley has a lower protein content than six-row barley, thus a more fermentable sugar content. High-protein barley is best suited for animal feed. Malting barley is usually lower protein[9] ("low grain nitrogen", usually produced without a late fertilizer application) which shows more uniform germination, needs shorter steeping, and has less protein in the extract that can make beer cloudy. Two-row barley is traditionally used in English ale-style beers. Six-row barley is common in some American lager-style beers, especially when adjuncts such as corn and rice are used, whereas two-row malted summer barley is preferred for traditional German beers.

Hulless barley

Hulless or "naked" barley (Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum Hook. f.) is a form of domesticated barley with an easier-to-remove hull. Naked barley is an ancient food crop, but a new industry has developed around uses of selected hulless barley to increase the digestible energy of the grain, especially for swine and poultry.[10] Hulless barley has been investigated for several potential new applications as whole grain, and for its value-added products. These include bran and flour for multiple food applications.[11]

Classification

In traditional classifications of barley, these morphological differences have led to different forms of barley being classified as different species. Under these classifications, two-rowed barley with shattering spikes (wild barley) is classified as Hordeum spontaneum K. Koch. Two-rowed barley with nonshattering spikes is classified as H. distichum L., six-row barley with nonshattering spikes as H. vulgare L. (or H. hexastichum L.), and six-row with shattering spikes as H. agriocrithon Åberg.

Because these differences were driven by single-gene mutations, coupled with cytological and molecular evidence, most recent classifications treat these forms as a single species, H. vulgare L.[6]

Cultivars

- Vocabulary

- DON: Acronym for deoxynivalenol, a toxic byproduct of Fusarium head blight, also known as vomitoxin.

- Heading date: A parameter in barley cultivation.[12]

- Lodging: The bending over of the stems near ground level.

- Nutans: A designation for a variety with a lax ear, as opposed to 'erectum' (with an erect ear).

- QCC: A pathotype of stem rust (Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici).

- Rachilla: The part of a spikelet that bears the florets. The length of the rachilla hairs is a characteristic of barley varieties.

- Cultivars

- 'Azure', a six-rowed, blue-aleurone malting barley released in 1982. It was high-yielding with strong straw, but was susceptible to loose smut.

- 'Beacon', a six-rowed malting barley with rough awns, short rachilla hairs and colorless aleurone. Released in 1973, it was the first North Dakota State University (NDSU) barley that had resistance to loose smut.

- Bere, a six-row barley currently cultivated mainly on 5-15 hectares of land in Orkney, Scotland.

- 'Betzes', an old German two-row barley introduced into North America from Kraków, Poland, by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).[13] The Montana and Idaho agricultural experiment stations released Betzes in 1957. It is a midshort, medium-strength-strawed, midseason-maturing barley. It has a midsize-to-large kernel with yellow aleurone. Betzes is susceptible to loose and covered smuts, rusts, and scald.

- 'Bowman', a two-rowed, smooth-awned variety jointly released by NDSU and USDA in 1984 as a feed barley spring variety developed in North Dakota. It has good test weight and straw strength. It is resistant to wheat stem rust but is susceptible to loose smut and barley yellow dwarf virus.

- 'Celebration', a variety developed by the barley breeding program at Busch Agricultural Resources and released in 2008. Through a collaborative agreement between the North Dakota State University Foundation Seedstocks (NDFSS) project and Busch Agricultural Resources, all foundation seed of Celebration barley will be produced and distributed by the NDFSS. Celebration has excellent agronomic performance and malt quality. It is a Midwestern variety, well-adapted for Minnesota, North Dakota, Idaho, and Montana, with medium-early maturity, medium-early heading, medium-short height, mid-lax head type, rough awns, short rachilla hairs, and colorless aleurone, moderately resistant to Septoria and net blotch. It has improved reaction to Fusarium head blight and consistently lower DON content.

- 'Centennial', a Canadian variety developed from the cross of Lenta x Sanalta by the University of Alberta. It is a two-row, relatively short, stiff-strawed, late-maturing variety. The kernel is midlong with yellow aleurone. It was released as a feed barley.

- 'Compana', an American variety developed from a composite cross by the Idaho and Montana Agricultural Experiment Stations in cooperation with the USDA's Plant Science Research Division. It was released by Montana in 1941. Compana is a two-row variety with moderately weak straw, midshort with midseason maturity. The kernels are long and wide with yellow aleurone. This variety is resistant to loose smut and moderately resistant to covered smut.

- 'Conlon', a two-row barley released by NDSU in 1996. Test weight and yield is better than Bowman. Yield is equal to Stark. Conlon heads earlier than Bowman and shows good heat tolerance by kernel plumpness. It is resistant to powdery mildew and net blotch but is moderately susceptible to spot blotch. It is prone to lodging under high-yield growing conditions. It appears best adapted to western North Dakota and adjacent western states.

- 'Diamant', a Czech high-yield, short-height, mutant variety created with X-rays.

- 'Dickson', a six-row, rough-awned variety released by NDSU in 1965. It had good straw strength and was resistant to stem rust but susceptible to loose smut. Dickson had more resistance to prevalent leaf spot diseases than Trophy, Larker and Traill. It was similar to Trophy in heading date, plant height and straw strength. It had less plumpness than Trophy and Larker but more than Traill and Kindred.

- 'Drummond', a six-row malting variety released by NDSU in 2000. It has white aleurone, long rachilla hairs and semi-smooth awns. Drummond has better straw strength than current six-row varieties. Heading date is similar to Robust and plant height is similar to Stander. It is resistant to spot blotch and moderately susceptible to net blotch. However, its net blotch resistance is better than any current variety. Fusarium head blight reaction is similar to that of Robust. It is resistant to prevalent races of wheat stem rust but is susceptible to pathotype Pgt-QCC. Drummond is on the American Malting Barley Association's list of recommended varieties. In two years of plant scale evaluation, Drummond was found satisfactory by Anheuser-Busch, Inc. and Miller Brewing.

- 'Excel', a six-row, white-aleurone malting barley released by Minnesota in 1990. Shorter in height than other six-row barleys grown at that time, it is high-yielding with medium-early maturity, moderately strong straw, smooth awns and long rachilla hairs. It has high resistance to stem rust and moderate resistance to spot blotch but is susceptible to loose smut. Malting traits are equal or greater than Morex with plum kernel percentage lower than Robust.

- 'Foster', a six-row, white-aleurone malting barley released by NDSU in 1995. About one day earlier and slightly shorter than Robust, it is higher-yielding than Morex, Robust and Hazen. Straw strength is similar to Excel and Stander but better than Robust. It is moderately susceptible to net blotch but resistant to spot blotch. Protein is 1.5 percent lower than Robust and Morex.

- 'Glenn', a six-row, white-aleurone variety released by NDSU in 1978. Glenn was resistant to prevalent races of loose and covered smut with better resistance to leaf spot diseases than Larker. It matured about two days earlier than Larker and yielded about 10 percent more than Larker and Beacon.

- 'Golden Promise', an English semi-dwarf, salt-tolerant mutant variety (created with gamma rays) used to make beer and whiskey.

- 'Hazen', a six-row, smooth-awn, white-aleurone feed barley released by NDSU in 1984. Hazen heads two days later than Glenn. It is susceptible to loose smut.

- Highland barley, a crop cultivated on the Tibetan Plateau.

- 'Kindred', released in 1941 and developed from a selection made by S.T. Lykken, a Kindred, North Dakota farmer. It was a six-row, rough-awned, medium-early Manchurian-type malting variety that gave good yields. Kindred had stem rust resistance but was moderately susceptible to spot blotch and Septoria. It was less susceptible to blight and root rot than Wisconsin 38. It was medium-height with weak straw.

- 'Kindred L', a re-selection made to eliminate blue Manchurian types.

- 'Larker', a six-rowed, semi-smooth-awn malting barley first released in 1961. It was medium-maturity with moderate straw strength and medium height. Larker was rust-resistant but susceptible to leaf diseases and loose smut. It was superior to all other malt varieties for kernel plumpness at the time of release.

- 'Logan', released by NDSU in 1995, is classed as a non-malting barley. It is a white-aleurone, two-row barley similar to Bowman in heading date and plant height and similar to Morex for foliar diseases. It has better yield, test weight, and lodging score, and lower protein, than Bowman and Morex.

- 'Lux', a Danish variety.[14]

- 'Manchurian', a blue-aleurone malting variety released by NDSU in 1922. It had weak to moderate-stiff straw and was susceptible to stem rust. It was developed from false stripe virus-free stock.

- 'Manscheuri', also designated Accession No. 871, a six-row barley that may have been first released by NDSU before 1904. It outyielded most of the common types being grown in North Dakota at the time. It had stiffer straw than varieties at the time and a longer head filled with large, plump kernels.

- 'Mansury', also designated Accession No. 172, a two-row barley first released by NDSU in about 1905.

- Maris Otter, an English two-row winter variety commonly used in the production of malt for the brewing industry, no longer on the recommended list of approved malting barley varieties.

- 'Morex', a six-row, white-aleurone, smooth-awn malting variety released by Minnesota in 1978. Morex, which stands for "more extract", is highly resistant to stem rust, moderate to spot blotch and susceptible to loose smut.

- 'Nordal', a spring nutans variety from Carlsberg, Sweden released in 1971.[15][16]

- 'Nordic', a six-rowed, colorless-aleurone feed barley released in 1971. It had rough awns and short rachilla hairs. Yield was similar to Dickson but greater than Larker. Kernel plumpness and test weight was superior to Dickson but less than Larker. Lodging, spot and net blotch resistance was similar to Dickson but it had higher resistance to Septoria leaf blotch. It showed less leaf rust symptoms compared to other varieties at the time.

- 'Optic'

- 'Park', a six-row, white-aleurone malting barley released in 1978. Park had better resistance to leaf spot diseases, spot blotch, net blotch and Septoria leaf blotch than Larker.

- 'Plumage Archer', an English malt variety.

- 'Pearl'

- 'Pinnacle', a variety released by the North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station in 2006. Pinnacle has high yield, low protein, long rachilla hairs, smooth awns, white aleurone, medium-late maturity, medium height and strong straw strength.

- 'Proctor', a parent cultivar of 'Maris Otter'.

- 'Pioneer', a parent cultivar of 'Maris Otter'.

- 'Rawson', a variety developed by the NDSU Barley Breeding Program and released by the North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station in 2005. Rawson's general characteristics were very large kernels, loose hull, long rachilla hairs, rough awns, white aleurone, medium maturity, medium height, and medium straw strength.

- 'Robust', a six-row, white-aleurone malting variety released by Minnesota in 1983. Maturity is two days later than Morex.

- 'Sioux', a selection from Tregal released by NDSU. It was a six-row, medium-early variety with white aleurone, rough awns and long rachilla hairs. It was high-yielding with plump kernels. Its disease reaction was similar to Tregal.

- 'Stark', a two-row non-malting barley released by NDSU in 1991. It has stiff straw and large kernels, and appears best adapted to western North Dakota and adjacent western states. Stark is about one day later and two inches shorter to Bowman, with equal or better test weight. Stark yields about 10 percent better than Bowman. It is moderately resistant to net and spot blotch but is susceptible to loose smut, leaf rust and the QCC race of wheat stem rust.

- 'Tradition', a variety with excellent agronomic performance and malt quality, well-adapted to Minnesota, North Dakota, Idaho and Montana. Tradition has medium relative maturity, medium-short height, and very strong straw. Tradition has a nodding head type, semi-smooth awns, long rachilla hairs and white aleurone.

- 'Traill', a medium-early, rough-awn, white-aleurone malting variety released by NDSU in 1956. It was resistant to stem rust and had the same reaction to spot blotch and Septoria as Kindred. Traill had greater yield and straw strength than Kindred but had smaller kernel size.

- 'Tregal', a high-yield, smooth-awn, six-row feed barley released by NDSU in 1943. It was medium-early with short, stiff straw, erect head, and high resistance to loose smut. Tregal was similar to Kindred for reaction to spot blotch with similar tolerance to Septoria.

- 'Trophy', a six-row, rough-awn malting variety with colorless aleurone released by NDSU in 1964. Similar to Traill and Kindred in plant height, heading date and test weight, it had a higher percentage of plump kernels. Its yield in North Dakota was greater than Kindred and similar to Traill. Similar to Kindred and Traill, it was resistant to stem rust but susceptible to loose smut and Septoria leaf blotch. Trophy had some field resistance to net blotch. It had greater straw strength than Kindred. Trophy had greater enzymatic activity and quality than Traill.

- 'Windich', a Western Australian grain cultivar named after Tommy Windich (c. 1840–c. 1876).

- 'Yagan', a Western Australian grain cultivar named after Yagan (c. 1795-1833).

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

History

Barley was one of the first domesticated grains in the Fertile Crescent, an area of relatively abundant water in Western Asia, and near the Nile river of northeast Africa.[18] The grain appeared in the same time as einkorn and emmer wheat.[19] Wild barley (H. vulgare ssp. spontaneum) ranges from North Africa and Crete in the west, to Tibet in the east.[6] The earliest evidence of wild barley in an archaeological context comes from the Epipaleolithic at Ohalo II at the southern end of the Sea of Galilee. The remains were dated to about 8500 BC.[6] The earliest domesticated barley occurs at aceramic ("pre-pottery") Neolithic sites, in the Near East such as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B layers of Tell Abu Hureyra, in Syria. By 4200 BC domesticated barley occurs as far as in Eastern Finland.[20] Barley has been grown in the Korean Peninsula since the Early Mumun Pottery Period (circa 1500–850 BC) along with other crops such as millet, wheat, and legumes.[21]

In the Pulitzer Prize-winning book Guns, Germs, and Steel, Jared Diamond argues that the availability of barley, along with other domesticable crops and animals, in southwestern Eurasia significantly contributed to the broad historical patterns that human history has followed over approximately the last 13,000 years; i.e., why Eurasian civilizations, as a whole, have survived and conquered others.[22]

Barley beer was probably one of the first alcoholic drinks developed by Neolithic humans.[23] Barley later on was used as currency.[23] Alongside emmer wheat, barley was a staple cereal of ancient Egypt, where it was used to make bread and beer. The general name for barley is jt (hypothetically pronounced "eat"); šma (hypothetically pronounced "SHE-ma") refers to Upper Egyptian barley and is a symbol of Upper Egypt. The Sumerian term is akiti. According to Deuteronomy 8:8, barley is one of the "Seven Species" of crops that characterize the fertility of the Promised Land of Canaan, and it has a prominent role in the Israelite sacrifices described in the Pentateuch (see e.g. Numbers 5:15). A religious importance extended into the Middle Ages in Europe, and saw barley's use in justice, via alphitomancy and the corsned.

| jt barley determinative/ideogram |

| ||||

| jt (common) spelling |

| ||||

| šma determinative/ideogram |

|

Rations of barley for workers appear in Linear B tablets in Mycenaean contexts at Knossos and at Micenaean Pylos.[24] In mainland Greece, the ritual significance of barley possibly dates back to the earliest stages of the Eleusinian Mysteries. The preparatory kykeon or mixed drink of the initiates, prepared from barley and herbs, referred in the Homeric hymn to Demeter, whose name some scholars believe meant "Barley-mother".[25] The practice was to dry the barley groats and roast them before preparing the porridge, according to Pliny the Elder's Natural History (xviii.72). This produces malt that soon ferments and becomes slightly alcoholic.

Pliny also noted barley was a special food of gladiators known as hordearii, "barley-eaters". However, by Roman times, he added that wheat had replaced barley as a staple.[26]

Tibetan barley has been a staple food in Tibetan cuisine since the fifth century AD. This grain, along with a cool climate that permitted storage, produced a civilization that was able to raise great armies.[27] It is made into a flour product called tsampa that is still a staple in Tibet.[28] The flour is roasted and mixed with butter and butter tea to form a stiff dough that is eaten in small balls.

In medieval Europe, bread made from barley and rye was peasant food, while wheat products were consumed by the upper classes.[26] Potatoes largely replaced barley in Eastern Europe in the 19th century.[29]

Genetics

The genome of barley was sequenced in 2012.[30]

The genome is composed of seven pairs of nuclear chromosomes (recommended designations: 1H, 2H, 3H, 4H, 5H, 6H and 7H), and one mitochondrial and one chloroplastic chromosome, with a total of 5000 Mbp.[31]

Production

| Rank | Country | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | | 16.9 | 14.0 | 15.4 |

| 02 | | 8.7 | 10.4 | 10.3 |

| 03 | | 8.8 | 11.3 | 10.3 |

| 04 | | 7.8 | 8.0 | 10.2 |

| 05 | | 8.3 | 6.0 | 10.1 |

| 06 | | 7.6 | 7.1 | 7.9 |

| 07 | | 9.1 | 6.9 | 7.6 |

| 08 | | 8.0 | 8.2 | 7.5 |

| 09 | | 5.5 | 5.5 | 7.1 |

| 10 | | 4.1 | 5.2 | 4.7 |

| — | World total | 134.3 | 133.5 | 144.8 |

Barley was grown in about 100 countries worldwide in 2013. The world production in 1974 was 148,818,870 tonnes; since then, there has been a slight decline in the amount of barley produced worldwide.[26] Upon the results of 2011, Ukraine was the world leader in barley export.[33]

Cultivation

Barley is a widely adaptable crop. It is currently popular in temperate areas where it is grown as a summer crop and tropical areas where it is sown as a winter crop. Its germination time is one to three days. Barley grows under cool conditions, but is not particularly winter hardy.

Barley is more tolerant of soil salinity than wheat, which might explain the increase of barley cultivation in Mesopotamia from the second millennium BC onwards. Barley is not as cold tolerant as the winter wheats (Triticum aestivum), fall rye (Secale cereale) or winter triticale (× Triticosecale Wittm. ex A. Camus.), but may be sown as a winter crop in warmer areas of Australia and Great Britain.

Barley has a short growing season and is also relatively drought tolerant.[26]

Plant diseases

This plant is known or likely to be susceptible to barley mild mosaic bymovirus,[34][35] as well as bacterial blight. It can be susceptible to many diseases, but plant breeders have been working hard to incorporate resistance. The devastation caused by any one disease will depend upon the susceptibility of the variety being grown and the environmental conditions during disease development. Serious diseases of barley include powdery mildew caused by Blumeria graminis f.sp. hordei, leaf scald caused by Rhynchosporium secalis, barley rust caused by Puccinia hordei, and various diseases caused by Cochliobolus sativus. Barley is also susceptible to head blight.

Uses

Algicide

Barley straw, in England, is placed in mesh bags and floated in fish ponds or water gardens to help reduce algal growth without harming pond plants and animals. Barley straw has not been approved by the EPA for use as a pesticide and its effectiveness as an algicide in ponds has produced mixed results during university testing in the US and the UK.[36]

Animal feed

Half of the United States' barley production is used as livestock feed.[37] Barley is an important feed grain in many areas of the world not typically suited for maize production, especially in northern climates—for example, northern and eastern Europe. Barley is the principal feed grain in Canada, Europe, and in the northern United States.[38] A finishing diet of barley is one of the defining characteristics of western Canadian beef used in marketing campaigns.[39]

Fish feed

As of 2014, an enzymatic process can be used to make a high-protein fish feed from barley, which is suitable for carnivorous fish such as trout and salmon.[40]

Beverages

Alcoholic beverages

A large part (about 25%) of the remainder is used for malting, for which barley is the best-suited grain.[41] It is a key ingredient in beer and whisky production. Two-row barley is traditionally used in German and English beers. Six-row barley was traditionally used in US beers, but both varieties are in common usage now.[42] Distilled from green beer,[43] whisky has been made primarily from barley in Ireland and Scotland, while other countries have used more diverse sources of alcohol, such as the more common corn, rye and wheat in the USA. In the US, a grain type may be identified on a whisky label if that type of grain constitutes 51% or more of the ingredients and certain other conditions are satisfied.[44]

Barley wine is a style of strong beer from the English brewing tradition. Another alcoholic drink known by the same name, enjoyed in the 18th century, was prepared by boiling barley in water, then mixing the barley water with white wine and other ingredients, such as borage, lemon and sugar. In the 19th century, a different barley wine was made prepared from recipes of ancient Greek origin.[3]

Nonalcoholic beverages

Nonalcoholic drinks such as barley water[3] and barley tea (called mugicha in Japan)[45] have been made by boiling barley in water. In Italy, barley is also sometimes used as coffee substitute, caffè d'orzo (coffee of barley). This drink is obtained from ground, roasted barley and it is prepared as an espresso (it can be prepared using percolators, filter machines or cafetieres). It became widely used during the Fascist period and the war, as Italy was affected by embargo and struggled to import coffee. It was also a cheaper option for poor families (often grown and roasted at home) in the period. Afterwards, it was promoted and sold as a coffee substitute for children. Nowadays, it is experiencing a revival and it can be considered some Italians' favourite alternative to coffee when, for health reasons, caffeine drinks are not recommended.

Food

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,474 kJ (352 kcal) |

|

77.7 g | |

| Sugars | 0.8 g |

| Dietary fiber | 15.6 g |

|

1.2 g | |

|

9.9 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(17%) 0.2 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(8%) 0.1 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(31%) 4.6 mg |

|

(6%) 0.3 mg | |

| Vitamin B6 |

(23%) 0.3 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(6%) 23 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(0%) 0.0 mg |

| Trace metals | |

| Calcium |

(3%) 29.0 mg |

| Iron |

(19%) 2.5 mg |

| Magnesium |

(22%) 79.0 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(32%) 221 mg |

| Potassium |

(6%) 280 mg |

| Zinc |

(22%) 2.1 mg |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Barley contains eight essential amino acids.[46] According to a 2006 study, eating whole-grain barley can regulate blood sugar (i.e. reduce blood glucose response to a meal) for up to 10 hours after consumption compared to white or even whole-grain wheat, which have similar glycemic indices.[47] The effect was attributed to colonic fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates.

Hulled barley (or covered barley) is eaten after removing the inedible, fibrous, outer hull. Once removed, it is called dehulled barley (or pot barley or scotch barley).[48] Considered a whole grain, dehulled barley still has its bran and germ, making it a nutritious and popular health food. Pearl barley (or pearled barley) is dehulled barley which has been steam processed further to remove the bran.[48] It may be polished, a process known as "pearling". Dehulled or pearl barley may be processed into a variety of barley products, including flour, flakes similar to oatmeal, and grits.

Barley meal, a wholemeal barley flour lighter than wheat meal but darker in colour, is used in porridge and gruel in Scotland.[48] Barley meal gruel is known as sawiq in the Arab world.[49] With a long history of cultivation in the Middle East, barley is used in a wide range of traditional Arabic, Assyrian, Israelite, Kurdish, and Persian foodstuffs including kashkak, kashk and murri. Barley soup is traditionally eaten during Ramadan in Saudi Arabia.[50] Cholent or hamin (in Hebrew) is a traditional Jewish stew often eaten on Sabbath, in a variety of recipes by both Mizrachi and Ashkenazi Jews, with barley cited throughout the Hebrew Bible in multiple references. In Eastern and Central Europe, barley is also used in soups and stews such as ričet. In Africa, where it is a traditional food plant, it has the potential to improve nutrition, boost food security, foster rural development and support sustainable landcare.[51]

The six-row variety bere is cultivated in Orkney, Shetland, Caithness and the Western Isles in the Scottish Highlands and islands. The grain is used to make beremeal, used locally in bread, biscuits, and the traditional beremeal bannock.[52]

Like wheat and rye, barley contains gluten, which makes it an unsuitable grain for consumption by those with Coeliac disease.

Measurement

Barley grains were used for measurement in England, there being three or four barleycorns to the inch and four or five poppy seeds to the barleycorn.[53] The statute definition of an inch was three barleycorns, although by the 19th century, this had been superseded by standard inch measures.[54] This unit still persists in the shoe sizes used in Britain and the USA.[55]

The barleycorn was known as arpa in Turkish, and the feudal system in Ottoman Empire employed the term arpalik, or "barley-money", to refer to a second allowance made to officials to offset the costs of fodder for their horses.[56]

Ornamental

A new stabilized variegated variety of Hordeum vulgare, billed as Hordeum vulgare varigate, has been introduced for cultivation as an ornamental and pot plant for pet cats to nibble.[57]

Research

The chlorophyll-binding a/b protein is missing in albostrains of barley, and they have been used to study plastid development in plants. Researching white-streaked strains, plant scientists have gained a greater understanding of reporter gene expression in the production of chloroplast proteins.[58]

Cultural significance

The Islamic prophet Muhammad prescribed barley (talbina) for seven diseases.[59] It was also said to soothe and calm the bowels. Avicenna, in his 11th century work The Canon of Medicine, wrote of the healing effects of barley water, soup and broth for fevers.[60] Additionally, barley can be roasted and turned into roasted barley tea, a popular Asian drink.

In English folklore, the figure of John Barleycorn in the folksong of the same name is a personification of barley, and of the alcoholic beverages made from it, beer and whisky. In the song, John Barleycorn is represented as suffering attacks, death, and indignities that correspond to the various stages of barley cultivation, such as reaping and malting. He may be related to older pagan gods, such as Mímir or Kvasir.[61]

Chemistry

H. vulgare contains the phenolics caffeic acid and p-coumaric acid, the ferulic acid 8,5'-diferulic acid, the flavonoids catechin-7-O-glucoside,[62] saponarin,[63] catechin, procyanidin B3, procyanidin C2, and prodelphinidin B3, and the alkaloid hordenine.

References

Notes

- ↑ "Hordeum vulgare". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ "FAOSTAT". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Ayto, John (1990). The glutton's glossary : a dictionary of food and drink terms. London: Routledge. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-415-02647-4.

- ↑ J. Simpson, E. Weiner (eds), ed. (1989). "barley". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-861186-2.

- ↑ "Dictionary of the Scots Language: "DSL - DOST Bere, Beir"". Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Zohary, Daniel; Maria Hopf (2000). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 59–69. ISBN 0-19-850357-1.

- ↑ Dai, F.; Nevo, E.; Wu, D.; Comadran, J.; Zhou, M.; Qiu, L.; Chen, Z.; Beiles, A. et al. (2012). "Tibet is one of the centers of domestication of cultivated barley". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (42): 16969. doi:10.1073/pnas.1215265109.

- ↑ Komatsuda, T.; Pourkheirandish, M; He, C; Azhaguvel, P; Kanamori, H; Perovic, D; Stein, N; Graner, A et al. (2006). "Six-rowed barley originated from a mutation in a homeodomain-leucine zipper I-class homeobox gene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (4): 1424–1429. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608580104. PMC 1783110. PMID 17220272.

- ↑ Adrian Johnston, Scott Murrell, and Cynthia Grant. "Nitrogen Fertilizer Management of Malting Barley: Impacts of Crop and Fertilizer Nitrogen Prices (Prairie Provinces and Northern Great Plains States)". International Plant Nutrition Institute. Retrieved 2009-05-28.

- ↑ Bhatty, R.S. (1999). "The potential of hull-less barley". Cereal Chemistry 76 (5): 589–599. doi:10.1094/CCHEM.1999.76.5.589.

- ↑ Bhatty, R.S. (2011). "β-glucan and flour yield of hull-less barley". Cereal Chemistry 76 (2): 314–315. doi:10.1094/CCHEM.1999.76.2.314.

- ↑ Genetic analysis of heading date and other agronomic characters in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). J.H. Esparza Martínez and A.E. Foster, Euphytica, 03-1998, Volume 99, Issue 3, pages 145-153, doi:10.1023/A:1018380617288

- ↑ Wiebe, G.A.; Reid, D.A. (1961). Classification of Barley Varieties Grown in the United States and Canada in 1958. U.S. Department of Agriculture. p. 210.

- ↑ Identification of barley mutants in the cultivar ‘Lux’ at the Dhn loci through TILLING. S. Lababidi, N. Mejlhede, S. K. Rasmussen, G. Backes, W. Al-Said, M. Baum and A. Jahoor, Plant Breeding, August 2009, Volume 128, Issue 4, pages 332–336, doi:10.1111/j.1439-0523.2009.01640.x

- ↑ "Barley Pedigree Catalogue". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Biosynthesis of proanthocyanidins in barley: Genetic control of the conversion of dihydroquercetin to catechin and procyanidins. Klaus Nyegaard Kristiansen, Carlsberg Research Communications, January 1984, Volume 49, Issue 5, pages 503-524, doi:10.1007/BF02907552

- ↑ "Barley varieties developed at North Dakota State University". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Badr, A.; M, K.; Sch, R.; Rabey, H.E.; Effgen, S.; Ibrahim, H.H.; Pozzi, C.; Rohde, W.; Salamini, F. (2000). "On the Origin and Domestication History of Barley (Hordeum vulgare)". Molecular Biology and Evolution 17 (4): 499–510. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026330. PMID 10742042.

- ↑ -Saltini Antonio, I semi della civiltà. Grano, riso e mais nella storia delle società umane,, prefazione di Luigi Bernabò Brea Avenue Media, Bologna 1996

- ↑ "Maanviljely levisi Suomeen Itä-Aasiasta jo 7000 vuotta sitten - Ajankohtaista - Tammikuu 2013 - Humanistinen tiedekunta - Helsingin yliopisto". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Crawford, Gary W.; Gyoung-Ah Lee (2003). "Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula". Antiquity 77 (295): 87–95. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared M. (1997). Guns, germs, and steel: the fates of human societies. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 141. ISBN 0-393-03891-2.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Pellechia, Thomas (2006). Wine : the 8,000-year-old story of the wine trade. Philadelphia: Running Press. p. 10. ISBN 1-56025-871-3.

- ↑ John Chadwick, 1976. The Mycenaean World pp 118f et passim.

- ↑ J. Dobraszczyk, Bogdan (2001). Cereals and cereal products: chemistry and technology. Gaithersburg, Md.: Aspen Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 0-8342-1767-8.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 McGee 1986, p. 235

- ↑ Fernandez, Felipe Armesto (2001). Civilizations: Culture, Ambition and the Transformation of Nature. p. 265. ISBN 0-7432-1650-4.

- ↑ Dreyer, June Teufel; Sautman, Barry (2006). Contemporary Tibet : politics, development, and society in a disputed region. Armonk, New York: Sharpe. p. 262. ISBN 0-7656-1354-9.

- ↑ Roden, Claudia (1997). The Book of Jewish Food. Knopf. p. 135. ISBN 0-394-53258-9.

- ↑ Mayer, Klaus F. X.; Waugh, Robbie; Langridge, Peter; Close, Timothy J.; Wise, Roger P.; Graner, Andreas; Matsumoto, Takashi; Sato, Kazuhiro et al. (October 2012). "A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature11543. ISSN 0028-0836. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ↑ mapview. "barley genome at ncbi.nlm.nih.gov". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ FAOSTAT

- ↑ "Ukraine becomes world's third biggest grain exporter in 2011 - minister". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Brunt, A. A., Crabtree, K., Dallwitz, M. J., Gibbs, A. J., Watson, L. and Zurcher, E. J. (editors) (20 August 1996). "Plant Viruses Online: Descriptions and Lists from the VIDE Database".

- ↑ "Barley mild mosaic bymovirus".

- ↑ BTNY.edu

- ↑ "Barley". Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ↑ AG.ndsu.edu

- ↑ "OMAFRA.gov.on.ca". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Avant, Sandra (2014-07-14). "Process Turns Barley into High-protein Fish Food". USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ↑ McGee 1986, p. 471

- ↑ Ogle, Maureen (2006). Ambitious brew : the story of American beer. Orlando: Harcourt. pp. 70–72. ISBN 0-15-101012-9.

- ↑ McGee 1986, p. 481

- ↑ McGee 1986, p. 490

- ↑ Clarke, ed by R J (1988). Coffee. London: Elsevier Applied Science. p. 84. ISBN 1-85166-103-4.

- ↑ "Barley Grass: Amino Acids, Vitamins and Minerals". Womens-health-symmetry.com. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Nilsson, A. et al. (2006). "Effects of GI and content of indigestible carbohydrates of cereal-based evening meals on glucose tolerance at a subsequent standardised breakfast". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 60 (9): 1092–1099. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602423. PMID 16523203.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Simon, André (1963) Guide to Good Food and Wines: A Concise Encyclopedia of Gastronomy Complete and Unabridged p. 150 Collins, London

- ↑ Tabari, W. Montgomery Watt, M. V. McDonald (1987). The History of Al-Tabari: The Foundation of the Community: Muhammad at Al-Madina, A. D. 622-626/ijrah-4 A. H. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-344-2.

- ↑ Long, David E. (2005). Culture and customs of Saudi Arabia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 50. ISBN 0-313-32021-7.

- ↑ National Research Council (1996-02-14). "Other Cultivated Grains". Lost Crops of Africa: Volume I: Grains. Lost Crops of Africa 1. National Academies Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-309-04990-0. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ↑ Martin, Peter; Xianmin Chang (June 2008). "Bere Whisky: rediscovering the spirit of an old barley". The Brewer & Distiller International 4 (6): 41–43. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ↑ "Oxford English Dictionary". Oxford University Press. 2009.

- ↑ George Long (1842). "The Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge". C. Knight. p. 436.

- ↑ Cairns, Warwick (2007). About the Size of It. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-01628-6.

- ↑ Houtsma M Th; Arnold TW; Wensinck AJ (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. Brill. p. 460. ISBN 90-04-09796-1.

- ↑ "Variegated Cat Grass" (PDF).

- ↑ Jaiswal, Vijai Shanker; Ram, V. S. Jaiswal H. Y. Mohan (2000). The Changing Scenario in Plant Sciences. Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 299. ISBN 81-7764-021-6.

- ↑ Hadith. Volume 7, Book 71, Number 593: (Narrated 'Ursa)

- ↑ Scully, Terence; Dumville DN (1997). The art of cookery in the Middle Ages. Boydell Press. pp. 187–88. ISBN 0-85115-430-1.

- ↑ de Vries, Ad (1976). Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-7204-8021-3.

- ↑ Wolfgang Friedrich and Rudolf Galensa (2002). "Identification of a new flavanol glucoside from barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) and malt". European Food Research and Technology 214 (5): 388–393. doi:10.1007/s00217-002-0498-x.

- ↑ Kamiyama M, Shibamoto T (2012). "Flavonoids with Potent Antioxidant Activity Found in Young Green Barley Leaves". J. Agric. Food Chem. 60 (25): 6260–6267. doi:10.1021/jf301700j. PMID 22681491.

Bibliography

- McGee, Harold (1986). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Unwin. ISBN 0-04-440277-5.

External links

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barley". Encyclopædia Britannica 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barley". Encyclopædia Britannica 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - A Brief History of Barley Foods

- Cooking with barley and barley recipes

- Genetically modified barley - No effects on beneficial fungi Results of the safety research

- Barley from NutritionData

- Nutritive value of barley

- The National Barley Foods Council (NBFC) home page.

- Barley Information for Growers, eXtension

- Encyclopedia of Life

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||