Bannock War

| Bannock War | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

Bannock Shoshone Paiute | ||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

|

Buffalo Horn Egan | ||||

| Strength | |||||

| 900+ | 500 | ||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| 12-15 | 7-15 | ||||

The Bannock War of 1878 was an armed conflict between the U.S. military and Bannock and Paiute warriors in Southern Idaho and Northern Nevada, lasting from June to August 1878. The Bannock-Paiute totaled about 500 warriors; they were led by Chief Buffalo Horn who was killed in action in June. After his death, Chief Egan led the Bannock. He and some of his warriors were killed in July, by an Umatilla party who entered his camp in subterfuge.

The U.S. military, consisting of the 21st Infantry Regiment and volunteers, was led by Brigadier General Oliver O. Howard. Nearby states also sent militias to the region. The conflict ended in August and September 1878, when the remaining scattered Bannock-Paiute forces surrendered; many returned to Fort Hall Reservation. The US Army forced some 543 Paiute, from Nevada and Oregon, and Bannock prisoners to be interned at Yakama Indian Reservation in southeastern Washington Territory.

Background

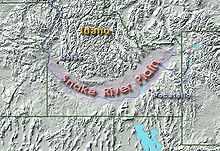

The Bannock people had developed as a distinct group from the Northern Paiute tribe of northern Idaho. During the 18th century, these Paiute had traveled south to the Snake River plain of present-day Idaho, attracted by the prospect of an alliance with the linguistically similar and equestrian Shoshone people. It was during this period that these Paiute became known as Bannock. The Bannocks quickly adopted the Shoshone’s equestrian culture and made other ties through intermarriage with the Shoshone. The Bannock, provided increased security and population for the Shoshone, who had lost many members due to epidemics of infectious disease contracted from Europeans.[1]

Arrival of European Americans

By the time the American Lewis and Clark Expedition arrived in this area of present-day southern Idaho in 1805, the Bannock-Shoshone had been trading for some time with representatives of the Hudson's Bay Company and North West Company from British Canada. They quickly opened trade with Americans for firearms and horses, as they had done with other European traders for years. The Shoshone-Bannock remained independent, despite their continued reliance on American trade. They participated in the Rocky Mountain fur trade, which ended about 1840.[2] This era of positive cooperation with American trade declined in the 1850s, along with the fur trade, under pressure of increased migration of Euro-Americans to the Snake Valley plain. The discovery of gold in the Boise Basin and the Beaverhead country of Montana had attracted prospectors and traders, who moved through the Snake region, competing for game and water resources as they traveled. The American traders and migrants were an established presence in the Snake region by the mid-1860s, affecting a vast majority of the Shoshone-Bannock inhabitants.[3]

The Shoshone-Bannock were dramatically influenced by arrival of Euroamericans and the rapid expansion of the trade-based economy. On a cultural level, the Euroamericans’ way of life challenged the values and seasonal traditions of the Shoshone-Bannock. New practices of agriculture, managing livestock, and production replaced the traditional resources on which the Shoshone-Bannocks had relied. They became more dependent on Euroamerican methods and products.[4]

American leaders were eager to acquire lands from the Shoshone-Bannock and in the 1860s, began to work to trade goods for titles to the Snake River Plains. The land trade attracted new waves of migrants to the Idaho territory, especially in the Boise region of the Snake Valley. In 1866, in order to protect the Shoshone-Bannock groups in the Boise Snake Valley from fearful and aggressive settlers, Governor Lyon created a refugee camp for a few hundred of the Bannock near Boise City. The camp's lack of sufficient resources forced the Shoshone-Bannock to depend on the local settlers for work and food. Many Shoshone-Bannock asked to be given the security of their own reservation land.[5]

The proposed relocation to eastern Idaho challenged the Shoshone-Bannock cosmology and their religious connection to the land, as their cultural practices were based in local seasonal changes in the Snake Valley. They believed their ancestors’ spirits still resided in the land.[6] Leadership among the Shoshone-Bannock was believed to be directly connected to the land which these ancestors inhabited, granting the chief his position. After complex and controversial deliberation, the Shoshone-Bannock leaders and American government officials formally agreed to relocate the Boise refugees to the Fort Hall Reservation. They completed relocation in 1869.[7]

Life at Fort Hall

The Fort Hall Reservation was a 1.8 million-acre plot along the Upper Snake River in eastern Idaho, on the river's southeastern banks. The region had potential for irrigation and agriculture. But, the Shoshone-Bannock faced immediate survival challenges due to their subsistence-based lifestyle, which could not be supported by resources in this region. The population was very dense for the land, numbering 1,037 in 1872. The Shoshone-Bannock struggled to live by subsistence.

The government made sizable appropriations to purchase the supplies necessary to feed the community. Food crises arose during the winters of 1874-1875 and 1876-1877, resulting from diminished game for hunters and a lack of adequate food supplies by the government. Many Shoshone-Bannock left Fort Hall to attempt survival on their own.[8] Simultaneously, the 1877 Nez Perce War drove officials to crack down on the tribe and require them to stay within the reservation boundaries.

The Bannock War of 1878 resulted from numerous factors.[9] The terrible conditions caused divisions within the Shoshone-Bannock communities. The Bannock began to view the Shoshone as intruders and committed theft and other crimes against the group. Friction between the Indians and the Euroamericans increased as well, resulting in violence when Pe-tope, a Fort Hill Indian, shot and wounded two teamsters in August 1877. Agent William Danilson, the government-appointed agent of the Fort Hall reservation at the time, pressed the tribal leaders to charge Pe-tope for the crime. In response to the crackdown, a friend of Pe-tope, Nampe-yo-go, killed Alexander Rhodan, a beef contractor for the reservation.[10]

Agent Danilson asked the tribe to capture the killer and turn him over to the US officials, but he was resisted by the Shoshone-Bannock. According to their tradition of reconciliation, they said it was the duty of the family of Nampe-yo-go to resolve his crime, not the tribe. That summer, a large number of the Shoshone-Bannock left the reservation, because of the lack of supplies, violence between the Indians and the Euroamericans, conflicts between the tribes, and Danilson's actions. This sparked the Bannock War of 1878, as the US government ordered the Army to return the people to the reservation to control them.[11]

The Battles

Camas Prairie

In May 1878, Chief Buffalo assembled 200 Bannock warriors from Fort Hall at Payne’s Ferry on the Snake River, moving to the Big Camas Prairie to set up camp. At that time the region between the Big Camas Prairie and the Snake River was occupied by a few white settlers, 2500 cattle, and 80 horses.[12] On May 30 the Bannock group, after trying to sell a buffalo skin robe to cowboys on the plain, shot two in an altercation. Lou Kensler and George Nesby survived their wounds and traveled with the third member of their party, William Silvey, to the nearby Baker’s camp.[13] Not long after this incident, the Bannock at a camp near the Lava Beds were attacked by white men. They killed a settler in the conflict but lost their camp's resources.

The news of the increased violence spread to Idaho's state capital in Boise City. Governor Brayman notified Brigadier General O. O. Howard, commander of the Military Department of the Columbia. Brayman wrote in a May 30 letter that he had dispatched Col. Bernard’s cavalry from Boise to the plains that evening as a show of force; he did not want to provoke further conflict.[14] Bernard’s cavalry reached the Bannock camp on June 2 and drove them to retreat to the Lava Beds. The military noted this was better for defense.[15] The Bannock group moved west and raided Glenn’s Ferry and King Hill station, both on the Snake River. Next, they moved along the river, killing several settlers along the way.[16] Bernard’s cavalry traveled by road to Rattlesnake station, where they joined with more military cavalry, as well as local militia volunteers from Alturas.[17] At this time, Bernard claimed there were 300 Bannock warriors in the Lava Beds, plus 200 who had raided Glenn’s Ferry and King Hill Station. The Bannock were rushing westward to meet with their Paiute allies, who were traveling down the Owyhee River to the Juniper Mountains and Lava Canyon.[18]

Conflicts between Army and Bannock

On June 8 a group of 26 volunteer military men from Silver City, Idaho, led by Captain J.B. Harber, encountered Chief Buffalo Horn and his warriors. At South Mountain, a small mining village, they exchanged fire, resulting in the deaths of two Silver City volunteers and several Bannock, among them the chief.[19] The Bannock selected a new leader, Chief Egan, and headed to Juniper Mountain in Idaho and Steens Mountain in southeastern Oregon to meet with the Paiute.[20] Other states began sending militia troops to the region, including California, Nevada, and Utah.[21]

As the Bannock traveled westward, they continued to raid camps, resulting in some settler deaths. People in Idaho and neighboring states feared that the violence would soon spread their way.[22] Bernard arrived in Silver City on June 9 and quickly headed out to the Jordan Valley. The troops moved to meet the Bannock at Steens Mountain. Bernard’s cavalry followed Chief Egan’s Bannock west into Oregon, eventually meeting them in battle on June 23 by Silver Creek.[23] The fight resulted in the deaths of three U.S. soldiers, the wounding of three others, and an unknown number of Bannock casualties. Col. Bernard moved to nearby Camp Curry to meet with General Howard on June 25.[24]

On June 29, there was a skirmish between the Bannock warriors and Crescent City volunteer militia. Bernard and his cavalry of 350 arrived shortly after and secured the city. The Bannock were traveling toward Fox Valley, estimated to number between 350 and 400. US forces thought they intended to travel further north to join the Cayuse and other Indian groups in that region who shared their discontent.[25]

Gen. Howard encountered the Bannock at the junction of Butter Creek and the Columbia River on July 7, resulting in conflict. Five U.S. soldiers were injured, and one died from his wounds. The fight resulted in an unknown number of casualties on the Bannock side, and they left going to the southeast.[26] The next fight occurred on July 12, when Captain Miles of the Umatilla Agency, a reservation near the Umatilla River whose people were potential allies of the Bannock band, accidentally encountered a large band of Umatilla warriors.[27] Feeling threatened by the increased movements of state militias around their territories, the Umatilla had ridden out in defense.[28] The Umatilla quickly surrendered and offered to fight with Miles against the Bannock. Historian Brigham D. Madsden suggested they were attracted to the high bounty that had been placed on Chief Egan’s head.[29] The conflict resulted in the deaths of five Bannock warriors and their eventual flight.

That night, Umatilla leaders pursued the Bannock. They entered the camp posing to conduct negotiations, and killed Chief Egan and several other warriors.[30][31] On July 20 one of Bernard’s battalions, under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Forsyth, met the Bannock forces in the canyon of the North Fork of the John Day River.[32] The conflict did not result in many casualties, but interrupted the Bannock, forcing their retreat.[33]

By July 27, Gen. Howard's strategy changed from one against a united enemy to pursuing the fractured Bannock groups. He had numerous Army units operating in Idaho.[34] Most of the concluding conflicts between the remaining bands and the military were led by Miles in August and September. The rest of the Bannock returned to the Fort Hall Reservation or pursued peaceful hunting on their own in groups.[35] A few more skirmishes between the scattered Bannock and military forces occurred, such as on August 9 in Bennett’s Creek by the Snake River, but no casualties were recorded.[36]

Aftermath

After the Bannock War of 1878, the American government restricted the movements of the Bannock in and out of the Fort Hall Reservation. Connections with other tribal groups were restricted, as well as the Bannock freedom to use local resources. Subdued from the battles and lack of resources, the Bannock worked to construct community within the reservation.[37]

Other Bannock and Paiute prisoners were interned at the Malheur Reservation in Oregon. While the Paiute had been more peripherally involved, in November 1878, General Howard moved about 543 Bannock and Paiute prisoners from the Malheur Reservation to internment at Yakama Indian Reservation in southeastern Washington Territory.[38] They suffered privation for years. In 1879 the Malheur Reservation was closed, "discontinued" through pressure from settlers.[38][39]

Northern Paiute from Idaho and Nevada were eventually released and relocated from Yakama to an expanded Duck Valley Indian Reservation with their Western Shoshone brethren in 1886.[40]

References

- ↑ Heaton, John W. (2005). The Shoshone-Bannocks : Culture & Commerce at Fort Hall, 1870-1940. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0700614028.

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, pp. 32-33

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, p. 37

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, pp. 30-31

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, p. 41

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, p. 43

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, p. 45

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, pp. 48-49

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, p. 50

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, pp. 50-51

- ↑ Heaton, John W. (2005). The Shoshone-Bannocks : culture & commerce at Fort Hall, 1870-1940. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 51. ISBN 0700614028.

- ↑ Brimlow, George Brimlow (1938). The Bannock Indian War of 1878. Caldwell, Idaho: The Caxton Printers Ltd. p. 74.

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 75

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 80

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 81

- ↑ Madsen, Brigham D (1948). The Bannock Indians in Northwest History. California: University of California. p. 187.

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 82

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 88

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 91

- ↑ Madsden (1948), Bannock Indians in Northwest History, p. 189

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 93

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 94

- ↑ Madsden (1948), Bannock Indians in Northwest History, p. 190

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 125

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 129

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 143

- ↑ Madsden (1948), Bannock Indians in Northwest History, p. 191

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 149

- ↑ Madsden (1948), Bannock Indians in Northwest History, p. 192

- ↑ "Native American History: The Bannock War".

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 151

- ↑ Madsden (1948), Bannock Indians in Northwest History, p. 192

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 152

- ↑ Madsden (1948), Bannock Indians in Northwest History, p. 193

- ↑ Madsden (1948), Bannock Indians in Northwest History, p. 197

- ↑ Brimlow (1938), Bannock Indian War of 1878, p. 159

- ↑ Heaton (2005), The Shoshone-Bannocks, pp. 55–56

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Brimlow, George Francis. Harney County and Its Range Land, Portland, Oregon: Binfords & Mort, 1951, pp. 81-130

- ↑ "Settling Up the Country: Social Costs of the Cattlemen's Era", The Oregon History Project

- ↑ "Cultural Department". Sho-Pai Tribes. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

Further reading

- Brimlow, George Brimlow (1938). The Bannock Indian War of 1878. Caldwell, Idaho: The Caxton Printers Ltd.

- Kessel, W. B. (2005). Encyclopedia of Native American Wars and Warfare. New York: Infobase Publishing.

- Madsen, Brigham D (1948). The Bannock Indians in Northwest History. California: University of California.

- Purvis, Thomas L. "Bannock—Paiute campaign. A Dictionary of American History". Blackwell Reference Online. Retrieved 28 February 2013.